When, one hundred years ago, the Russian people overthrew the centuries-old tsarist autocracy and, only months later, declared the beginning of a new stage in world history with the advent of soviet power.

The impact on political consciousness was global. In the US, the Revolution signalled a new stage in the development of revolutionary forces, as splits in the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) eventually produced the Communist Party.

At the same time, a new militancy was evident among African Americans, who continued to face discrimination after moving in their thousands from conditions of Jim Crow and sharecropping in the South to northern urban metropolises, and even after having served in the so-called Great War.

One man straddled both revolutionary crystallisations, and his name was Claude McKay.

Though he is not a renowned figure today, one image of McKay has become emblematic of the relationship that developed between the new, revolutionary Soviet state in Russia, and the worldwide anti-racist and anti-colonial struggles with which it was contemporary.

In the photograph above, McKay is seen addressing an audience of eminent revolutionaries in the Throne Room of the Kremlin, at the Fourth Congress of the Communist International.

The image signals the role played by McKay in linking the Revolution in Russia to what has been called the New Negro Movement – a broad term encompassing the new mass political consciousness of African Americans following World War One. The most significant political component of the New Negro Movement was Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which probably ranks as one of the largest mass movements in history.

Beyond curiosities such as this photograph, the details of McKay’s life and politics are not widely known. McKay’s biography is nevertheless a subject which can provide historical insight and political lessons for revolutionaries today.

Early life

Festus Claudius McKay was born to a family of the Jamaican middle peasantry in 1890. In 1907, he met Walter Jekyll, an English gentleman living in what was still a British colony. Under Jekyll’s guidance, McKay developed into a recognised poet. While he spent time working in the Jamaican constabulary in Kingston, writing was his passion and in 1912 he published his first collections of poetry, Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads, both written in Jamaican dialect. In August of the same year, McKay left Jamaica for the United States, never to return to his homeland.

McKay’s intention when he departed for the US was to study. But after a brief stint at the Tuskegee Institute, he transferred to Kansas State College, where he remained for two years. Not coincidentally, it was in Kansas, a state with a strong radical history, that McKay began to expand his political horizons, reading W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folks and, more than likely, encountering the Debsian and Wobbly varieties of socialism.

Finally, however, McKay’s studies of agronomy ground to a halt; he left Kansas and moved to New York, where he was married. His foray into domestic life was short-lived: the restaurant McKay took ownership over had to close, and his marriage ended while his only child was still a baby. He never saw the child again, and ignored his ex-wife’s occasional correspondences.

During the middle years of the 1910s, McKay took a string of low-paid jobs, the only jobs readily available to black men in America. McKay’s interest in radical politics was channelled primarily into his readership of the Masses magazine, a New York-based journal which reported positively on the activities of the IWW and – significantly for McKay – published sympathetic and artful depictions of the plight of black Americans.

In this period, McKay briefly joined the IWW while working at a factory, and associated with Hubert Harrison, who was one of the primary figures of black radicalism at the time. A socialist, a notable orator, and a writer, Harrison exercised significant influence on McKay and a whole layer of young and radical-minded people in New York in the 1910s.

After a series of failed attempts to get his poetry published in the Masses, McKay had a poem published in the Masses’ successor The Liberator in April 1919. It was the beginning of a long association between McKay and the Liberator, and most importantly with the guiding spirits of the journal: Max and Crystal Eastman. The Eastmans and McKay soon fostered what would prove a lifelong friendship, and their respective political roles would chime more than once.

After a series of failed attempts to get his poetry published in the Masses, McKay had a poem published in the Masses’ successor The Liberator in April 1919. It was the beginning of a long association between McKay and the Liberator, and most importantly with the guiding spirits of the journal: Max and Crystal Eastman. The Eastmans and McKay soon fostered what would prove a lifelong friendship, and their respective political roles would chime more than once.

McKay in this period began to play the role of an artistic conduit in America for what was a rising and worldwide revolutionary tide. His most famous poem, the 1919 sonnet ‘If We Must Die’, was taken up as a rallying cry across the US, and has had a long life since as a paean to resistance, in a language which is noticeably raceless.

New Negro Movement

In 1917, the revolution in Russia had captured the attention, admiration, and imagination of millions of oppressed people across the world, and the call for socialist revolution and national self-determination found great echoes far outside of Europe. In colonial nations such as Ireland and India, the revolutionary upturn was expressed in huge movements for national independence, within which class struggle was a primary feature.

The militant zeitgeist was echoed in the US by W.E.B. Du Bois, probably the leading African American intellectual of the 20th century, whose imploring of black Americans to participate loyally in the imperialist war a few years earlier was replaced in May 1919 in his short article ‘Returning Soldiers’, with a call to transform the war in Europe into a militant movement for racial justice in America.

McKay’s poems and Du Bois’s journalism were gaining ground amidst severe race riots, which led the summer of 1919 to go down in history as the Red Summer. Experiences such as those of Summer 1919 combined with the war, the global revolutionary conflagration, and the urbanisation of black Americans served to revolutionise black political consciousness. This was the New Negro movement.

Marcus Garvey’s UNIA was by far the largest and most significant component of the New Negro movement. But New Negro ideology had multiple expressions both within and outside the UNIA. Inside the UNIA, particularly in its early period, an ambivalent attitude to the ideas of communism was taken, with white communist Rose Pastor Stokes being an invited speaker at a UNIA congress. Furthermore, much of the thrust of UNIA activism, in spite of grand talk of a “return” to Africa, was centred on black civil rights within America and spoke to combatting internalised racism among African Americans.

Outside the UNIA, a small but influential crop of black leaders emerged who attempted to marry the struggle for racial justice with class struggle doctrines. People such as W.A. Domingo, A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, Cyril Briggs, and Grace Campbell emerged around papers like The Messenger and The Crusader.

While the Socialist Party, with which Randolph and Owen were associated, never sunk deep roots into the black working class, and the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) – whose members included Briggs, Campbell and McKay – was never more than a small secret society, these figures exercised a disproportionate influence. Their political programmes, however, ranged from an at times treacherous reformism to a sectarian black nationalism advocated by Briggs and co.

Famously, the New Negro movement also had a major cultural component, usually given the name of “the Harlem Renaissance”. Partially the product of conscious efforts on the part of the black intelligentsia to foster a new black literature and art, the Harlem Renaissance gave birth to the careers of many famous cultural figures, including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, Lois Mailou Jones, Jacob Lawrence, and Claude McKay. Among its trademarks was a fascination with Africa and “the primitive”, as well as musical forms such as jazz and the blues. It looked to the literary movements which developed around national liberation struggles across the world, including Mexican indigenismo and the Irish Literary Revival, for its models.

Troubadour

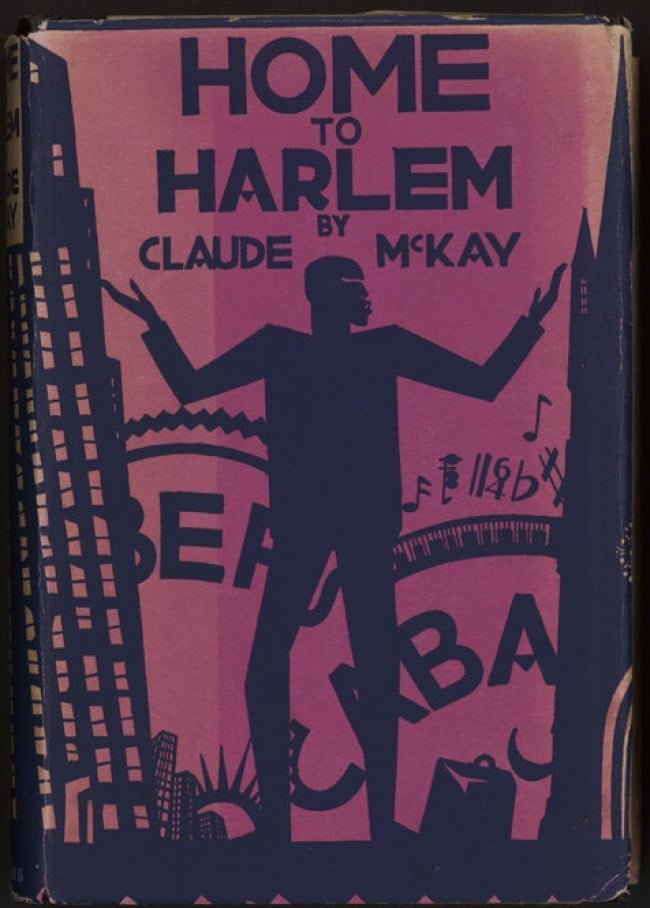

McKay’s relationship with these movements was contradictory. On the one hand, he was integral to the Harlem Renaissance, his iconic poem ‘If We Must Die’ and debut novel Home to Harlem being some of the most significant contributions to that movement. Yet he spent much of the 1920s – the height of the Renaissance – outside of the US, and held most of the black intelligentsia in contempt. He wrote mixed things about Garvey throughout his life; and while not part of the UNIA, his membership of the ABB evidences a nascent black nationalist aspect to his politics.

McKay’s relationship with these movements was contradictory. On the one hand, he was integral to the Harlem Renaissance, his iconic poem ‘If We Must Die’ and debut novel Home to Harlem being some of the most significant contributions to that movement. Yet he spent much of the 1920s – the height of the Renaissance – outside of the US, and held most of the black intelligentsia in contempt. He wrote mixed things about Garvey throughout his life; and while not part of the UNIA, his membership of the ABB evidences a nascent black nationalist aspect to his politics.

Yet even his dalliances with Debsian socialism, the syndicalist Wobblies, and socialistic black nationalism in the ABB do not convey the full mixture of McKay’s politics. In 1919 he finally visited England, the imperial motherland which he had long idolised. Upon arrival, he was utterly disaffected, being unimpressed with both the country and the people. But he remained politically active – in Sylvia Pankhurst’s left-communist group around the Worker’s Dreadnought. Working at the Dreadnought, he wrote doggerel poems and journalistic pieces which condemned the concessions made by the reformist Labour movement to imperialism and racism.

In 1921, McKay returned to America and resumed his association with the Eastmans’ Liberator magazine, which for years had been publishing articles in support of the Russian Revolution, including much of John Reed’s material. McKay became an editor of the magazine in March. Working on the Liberator, McKay produced some of his most notable poetry and argued energetically for greater coverage of racial oppression in its pages. He also prioritised the formal qualities of the magazine’s cultural output, in defiance of the later Stalinist doctrines around proletarian literature. He also encouraged his comrades in the ABB to affiliate more closely with the official communist movement. It was in this period that he established himself as one of the foremost black communists in North America.

His political essays also reflect a maturation on his part, showcasing his politics in its positive and negative aspects. In an essay titled ‘How Black Sees Green and Red,’ McKay identified commonalities between the oppression faced by him as a black man in America and the Irish nation under British dominion. He argued in support of national-revolutionary struggles, but with the further contention that this anti-colonial nationalism acts as ‘an open door to Communism’. In that formulation, he gestured towards a conception of anti-colonial revolution as ‘permanent’ in Trotsky’s sense – that is, as moving inexorably in its completion toward the conquest of power by the workers and peasants themselves and the building of socialism internationally.

These basically correct and admirable formulations, though, were accompanied by a primitivist sensibility which owed more to his nostalgia for rural Jamaica and an aesthetic fascination with the premodern than to any of Marx’s writings. McKay dreamed of a communism which was rooted in rural simplicity and represented a rebellion against civilisation as such. This stands in opposition to communism as Marxists advocate, which is based on the development of the productive forces to the highest degree, but under the collective ownership and democratic control of the people rather than on the basis of the chaotic capitalist marketplace.

McKay also wrote extensively about the experience of racial oppression in the United States. He argued that the absence of any serious discussion of racism in the literature and programmes of socialists and communists in the US would spell doom for the socialist revolution in the country. Without a real cognisance and a distinct programmatic offering to African Americans who were subject to Jim Crow laws and the terror of white lynchers, he claimed that the socialists were facilitating in the division of the working class and the allegiance of the black masses – rural and urban – to the boss class against white workers. This was an insightful and necessary corrective to the American socialists, whose many political weaknesses included neglect of the question of racial oppression.

Clearly, a mixture of McKay’s experience as a black worker in the US, a comrade in the socialist movement in both the US and Britain, and his self-education in Marxist theory enabled him to develop many advanced conclusions. But his theoretical understanding was never complete, and his intellectual tastes were always somewhat eclectic. In later years, he claimed that he had never considered Marx a great economist, and preferred the bourgeois Mill. Over time, eclecticism would become an ascendant and finally dominant aspect of his political consciousness. In turn, this was linked with the material conditions of his existence, which consisted of an increasing disconnect from the labour movement and took on a semi-lumpen character.

Communist International

From 1922 to 1923, McKay took his convictions to the heart of worldwide revolutionary struggle at the time, Soviet Russia. There, he participated in the Fourth Congress of the Communist International (though not as an official delegate from the US – his membership of the Communist Party was not a matter of public record).

From 1922 to 1923, McKay took his convictions to the heart of worldwide revolutionary struggle at the time, Soviet Russia. There, he participated in the Fourth Congress of the Communist International (though not as an official delegate from the US – his membership of the Communist Party was not a matter of public record).

McKay worked with Japanese Communist Sen Katayama, among others, and somewhat against the official American delegation, to develop a serious perspective for revolution in America and for a policy on the problem of racism. His primary contribution to this discussion was his speech to the assembly, and a pamphlet called Negroes in America.

While the latter is a more historical and theoretical treatise which therefore contains elements of McKay’s typical eclectic attitude, his speech adopts a more serious and practical approach to issues of legality in America (a major, indeed a fetishised, concern of early American Communists), as well as celebrating the role of Marxists in the fight against racism. “The Third International,” he wrote, “stands for the emancipation of all the workers of the world, regardless of race or color, and this stand of the Third International is not merely on paper like the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America. It is a real thing.”

While in Russia, McKay also met with Trotsky, who he always considered the best of the leading Communists that he met. (He was never able to meet Lenin due to the latter’s illness.) McKay’s account of the meeting, and the brief correspondence between the two, are indicative of Trotsky’s thought on the problem of racism some years before his more famous conversations with CLR James.

Political drifting

Although impressed by Trotsky and enamoured of the Russian people, McKay’s visit to Soviet Russia marked the pinnacle of his involvement with revolutionary politics. Among the reasons for McKay’s move away from international communism are a lack of faith in the effectiveness of the American organisation, an impatience with their factionalism, and a concern for his “independence” as an intellectual.

When he left Russia, McKay began a long period of meandering travel and political drift. While he was deeply impressed by Trotsky and would align himself with the Opposition, in the company of his friend Max Eastman, he maintained a growing distance from the revolutionary parties. Scholar William Maxwell has argued that McKay carried on espionage work for the Soviet government through the 1920s, and this may well be accurate. But in his writing it was clear that Marxism and communism were receding from the horizon of his political vision.

This was particularly clear in his second novel, Banjo (1929). Set in Marseilles and chronicling the itinerant lives of young men from across the African diaspora, Banjo gives voice to McKay in his political drift. In it, primitivism, racial essentialism, and a kind of cultural nationalism are combined with a persistent commitment to romantic liberal values of universalism and individual liberty. Outrage at imperialist exploitation and racism, as well as sympathy with the working class, are evident; but they are coupled with, and ultimately subdued, by intellectual precociousness and eclecticism.

This drift persisted through the remainder of McKay’s self-imposed exile, in which time McKay drafted another novel titled Romance in Marseilles, and published two books: the short story collection Gingertown and the novel Banana Bottom.

Return to America

In 1934, however, McKay finally returned to the US. Arriving amidst the Depression and the resultant mass radicalisation, expressed in the birth of the industrial union movement, McKay was nevertheless politically unmoved. Indeed, if any move is detectable he shifted further to the right and emphasised more greatly his racial chauvinism.

In these years, two more books were published: Harlem Metropolis, a non-fiction account of contemporary Harlem which was far more sympathetic to Garveyism than communism; and A Long Way from Home, a memoir with a clear agenda to distance him from his communist past.

While much of American culture shifted left and came under the influence of the Communist Party, McKay revolted against the Stalinist’s usurpation of democratic procedure and their bureaucratic manoeuvring. His anti-Stalinist rebellion nevertheless took the impotent form of forging an “independent” press of the black intellectuals, in collaboration with individuals uninterested in socialism.

By the late 1930s, McKay was a political and cultural irrelevance, with sour relations to the very writers – Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison – who he had paved the way for. In his memoir, he restated his conviction that the future of humanity lay with some kind of common ownership, but in his political practice he abandoned any hope of such a revolutionary turn. He continued to profess sympathy for Trotsky, but had little to do with the International Opposition.

McKay’s increasingly ferocious opposition to the Communists is most evident in his final, and until now unpublished, novel Amiable with Big Teeth. This novel acts quite directly as a polemic against the Communist International and the many black intellectuals associated with it. It relies once again on primitivist and cultural nationalist tropes, and offers nothing in the way of socialist or revolutionary politics.

The final notable change in McKay’s life occurred when, driven by a paranoid belief that the Communists were conspiring against him and against all black people, McKay converted to Catholicism. Only a matter of years after the Catholic church had championed Franco in his victory over the Spanish revolution, McKay declared Catholicism the last hope in the struggle against Communism.

For the remaining years of his life, McKay was afflicted with ill-health. McKay died in 1948.

Lessons

By the end of his life a political deserter, McKay’s example nevertheless holds numerous lessons for us, one hundred years since he was caught up in the extraordinary revolutionary wave of the 1910s and 1920s.

The trajectory of his politics and his art are suggestive of how the fate of the Revolution in Russia shaped intimately the lives of millions of people across the world. Initially activated to political militancy by his experiences of American racism and by the American socialist movement, the Russian Revolution helped to broaden his political horizons, stimulated a study of Marxism, and helped him to shape the cultural and political life of the US in the 1920s.

As editor at the Liberator, and more especially in his trip to the Soviet Union, he helped to kick-start discussions of the problem of racial oppression in the US. Study of these problems now, in the age of Black Lives Matter, is of course paramount. He also drew attention to the many other failings of the early American communists, which it would take years to overcome.

But with the bureaucratisation and Stalinisation of the Communist International, and the consequent political catastrophes in country after country, McKay was disillusioned not only with the organisations of international communism but with some fundamental principles of socialism. Lacking faith in the working class and, increasingly, lacking any organic connection with the workers, his politics succumbed to various prejudices. All of this pervades his literary output, mostly to its detriment. Finally, having pre-empted in the 1920s the much wider involvement of black Americans in socialist politics that would occur in the Depression years, he also had the dubious honour of pioneering in the 1930s the desertion of revolutionary ideas by leading figures of the American left which would become such a trend in the McCarthyite decades of the 1940s and 1950s.

Each individual biography contains in microcosm processes which are also observable on the macro scale of society, and McKay’s is no different. These processes ought first and foremost to be understood rather than rashly judged.

Clearly, Claude McKay was a character capable of great eloquence in defence of freedom and beauty, whose experience of capitalism drove him into opposition to this diseased system. Yet, as the revolutionary tide ebbed and his class position changed, his creative vitality and political relevance waned. Intelligence and critical sharpness did not prevent him from making mistakes. His end was a tragic one.

Nevertheless, his life remains a source of important lessons and unique insights, and his best, most militant work can still be used to inspire us in the building of a revolutionary international capable of delivering a ‘death-blow’ to capitalism and all its attendant evils.