The pro-Palestine movement is being attacked through the curtailment of basic democratic rights. Meetings have been shut down. In some countries, demonstrations have been banned. And pro-Palestinian voices have been censored.

Communists must fight these attacks. We defend democratic rights, even in a bourgeois democracy. But we do so for our own reasons and in our own way, based on working-class struggle.

Bourgeois and petty-bourgeois liberals also talk about ‘defending democratic rights’. We have nothing in common with them.

Communists must link the struggle for democratic rights with the struggle for socialism.

Class struggle

Democratic rights are often presented as abstractions that stand above society.

In reality they are just a description, in legal jargon, of the existing social, political, and economic conditions in a given society. What fundamentally determines those conditions is the class struggle.

This is what Marx means when he wrote that: “The law can only be the ideal, self-conscious image of reality, the theoretical expression, made independent, of the practical vital forces.” By “practical vital forces”, Marx means the living forces of the class struggle.

Democratic rights came into being as a weapon of the bourgeoisie.

The English Revolution of the 17th century seated the capitalist class firmly in political power.

This was formalised with the sordid coup of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ in 1688 and the Bill of Rights of 1689. This was an agreement between the defeated aristocracy and the rising bourgeois class.

The Bill of Rights established the right of private property for all men, and of freedom of speech for MPs, so that they could speak out against infringements to the capitalist class.

This legislation required the Crown to seek consent from the House of Commons as representative of ‘the people’ – that is to say, the propertied classes who alone were enfranchised.

This dawn of democratic rights was the product of class struggle, arming the rising capitalist class with an arsenal to defend its interests.

The nascent bourgeoisie demanded the right to publish its opinions and demands; to hold meetings to discuss them; and to have its representatives protected from arbitrary punishment by the feudal establishment.

The bourgeois revolution is the origin of the democratic rights we have today: rights such as freedom of speech and freedom of association. They were weapons of the merchants and bankers against the feudal nobility.

Safety valve

Since then, the capitalist class has been forced to extend democratic rights to the working class. Even so, it has cynically used this to its advantage.

For the bourgeoisie, democratic rights were not only a weapon for felling feudalism. Today, such rights provide useful ‘safe channels’ for tying up the struggle of its new class enemy: the proletariat.

In periods of relative stability, democratic rights are used by the bourgeoisie as a safety valve to release some of the class pressures that build up within capitalist society.

Free and fair elections allow some bourgeois politicians to be voted out, while others are voted in – all without disturbing the functioning of the capitalist economy.

Freedom of speech and association, and tying representatives of the working class up in parliamentary talking shops, allows workers to give voice to their frustrations without actually having any material impact on the wealth and power of the rich.

Whether Labour or the Tories win the next election, for example, the policies will remain the same. As the Financial Times – the serious strategists of capital – wrote recently: “Politicians [of both parties] are imprisoned by the economics, their choices limited.” And it is the banks and big businesses who decide the economics.

In this respect, our democratic rights are just a costume of democracy and equality, providing cover for the dictatorship of the rich.

Alan Greenspan, the former chair of the US Federal Reserve, openly admitted this in 2007. He was asked in an interview who he would vote for in the presidential election. He said it didn’t matter because:

“[We] are fortunate that, thanks to globalisation, policy decisions in the US have been largely replaced by global market forces. National security aside, it hardly makes any difference who will be the next president. The world is governed by market forces.”

Democratic rights are therefore a valuable tool for the capitalist class today. They give the illusion of freedom while subjecting us to wage-slavery. This is why Lenin, in State and Revolution, said:

“The omnipotence of ‘wealth’ is more certain in a democratic republic [because] it does not depend on defects in the political machinery or on the faulty political shell of capitalism. A democratic republic is the best possible political shell for capitalism…it establishes its power so securely, so firmly, that no change of persons, institutions or parties in the bourgeois-democratic republic can shake it.”

Imperialism

Internationally, the western capitalist class even claims it is defending ‘democratic rights’ to justify imperialist aggression. The conflict between US imperialism and Russia being fought out in Ukraine is the most obvious example.

In July 2023, Joe Biden said that, in the form of Russia, the West is faced “with a threat to the peace and stability of the world, to democratic values we hold dear, to freedom itself.”

The same rhetoric was used to justify the western invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan when George Bush said, in 2005: “We fight today because Iraq now carries the hope of freedom in a vital region of the world, and the rise of democracy will be the ultimate triumph.”

Under the cover of exporting and defending ‘democratic rights’, western imperialism has extended its tentacles into one country after another, looting and plundering them.

Nowhere has this ‘democratic’ façade worn thinner than in the latest barbarity in Gaza. The same western ruling classes that denounced the trampling of Ukraine’s ‘right to self-determination’ are fully behind the crushing of the Palestinian people.

Workers’ struggle

The ruling class has long claimed that they stand for democracy, whilst communists allegedly oppose democratic freedom on principle. And yet what is the real picture today?

Amidst all the chatter about ‘defending our democratic values’, we are seeing pro-Palestine protests banned and hounded by the press; meetings cancelled; unions told what they can and cannot discuss; new laws against ‘extremism’ and against the right to strike.

‘Democratic rights’, a useful disguise for a dictatorship of the rich under certain conditions, can turn into their opposite when faced with rising class struggle.

In fact, even the most fundamental democratic rights possessed by workers today had to be fought for and conquered.

The Industrial Revolution produced intense class struggle in England – but this time not between the capitalists and the aristocracy, but between workers and capitalists.

Fearful of the ‘swinish multitude’, the government of capitalists and landlords introduced Combination Acts and Unlawful Oath Acts at the turn of the 19th century to ban workers’ organisations; they met workers’ protests with sabre-wielding yeomanry, as with the Peterloo massacre; and they applied duties to the cheap press to make agitational newspapers unaffordable for workers.

They wanted to stymie any possibility of workers using freedom of speech to agitate for better pay and conditions, and of using freedom of association to form trade unions and hold meetings.

Workers, for their part, began demanding equal voting rights, annual parliaments, an end to ‘rotten boroughs’, and the removal of politicians who put bourgeois interests above those of workers.

All the rights the bourgeoisie had demanded for use against the monarchy were now a threat to their own rule in the hands of the proletariat.

So from 1795 to 1848, the struggle over democratic rights became a key arena of the class struggle.

The right to freedom of association, and especially the right to form a trade union, was fought over bitterly. The right for workers to vote out MPs who acted against their interests was of central importance.

Chartism

The highest expression of working-class struggle at that time was the Chartist movement, whose central demands were purely democratic, but which was entirely a class-based movement.

The Chartist Reverend Stephens explained the link between democratic demands, and social and economic demands. He announced to a crowd of 200,000 in Lancashire: “This question of universal suffrage is a knife and fork question, a bread and cheese question.”

One worker put it even better, declaring the aim of the democratic demands of Charter to be “plenty of roast beef, plum pudding, and strong beer by working three hours a day”.

“Chartism is essentially social in nature, a class movement,” explained Engels at the time. “The ‘Six Points’ which for the radical bourgeois are the beginning and end of the matter… are for the proletarian a mere means to further ends. ‘Political power our means, social happiness our end,’ is now the clearly formulated war-cry of the Chartists.”

The Plug Plot of 1842 saw a general strike with the potential to bring down the government, and workers’ assemblies explicitly calling for the democratic demands of the Charter to be implemented and workers to take power.

The bourgeoisie had championed democratic rights in its struggle against feudalism. Their extension to the working class now threatened to devour the very system they had helped to create.

This was the first example of the double-edged nature of democratic rights. But there would be many more. Throughout history, every victory which has secured more democratic rights for workers was the result of ferocious class struggle.

Clampdown

In times of relative class peace, democratic rights are a tool for the bourgeoisie to provide a liberal gloss to its unbridled rule. In times of class war, they become a liability for the capitalist class – seized upon and linked to social and economic demands by class-conscious workers.

As a result, when capitalism enters into crisis, the ruling class discards its democratic costume, bares its teeth, and starts clamping down on basic rights.

Throughout the 1970s in Britain the class struggle began to heat up. Trade unions were strong and taking militant strike action.

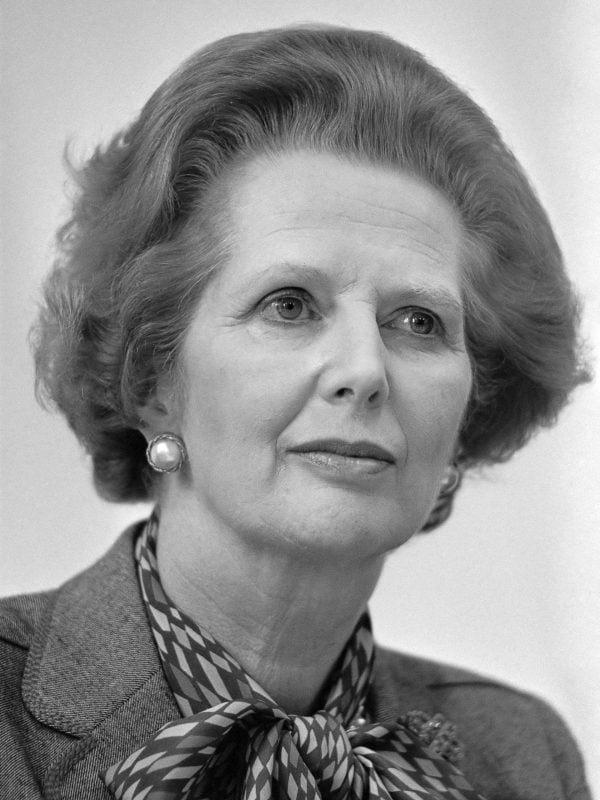

The ruling class needed to hit back, which they did in the 1980s with Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government. To carry out the instructions of the capitalist class, Thatcher trampled over democratic rights.

She massively restricted the right to strike; censored the British media over Ireland, by banning broadcasts of statements by Sinn Féin and other republicans; and incited the police to physically attack working-class youth, especially from Black and Asian communities.

The struggle to defend basic democratic rights, like freedom of association and free speech, became synonymous with defending working-class interests.

Today

In the more recent past, the rising class struggle of the last few years has led the Tory government to launch attacks on democratic rights – such as the right to strike and the right to protest.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing, and Courts Act of 2022 – introduced in response to the BLM and Sarah Everard demos, and direct action by Just Stop Oil, and Extinction Rebellion activists – imposed severe new restrictions on the right to protest.

And in response to the biggest wave of industrial action since the 1980s, the Tories have introduced laws requiring a minimum service in certain sectors even when they are on strike. This will effectively remove the right to strike from as many as 20 percent of workers.

The strength of the Palestine solidarity movement has led to a clampdown on rights to freedom of speech and assembly over the last few months. Universities and other venues have been cancelling pro-Palestine events, sometimes under direct pressure from the police. Journalists, trade unionists, and academics have faced the sack for expressing their views, and union branches are being told what they can and cannot discuss.

Despite 76 percent of people supporting ‘an immediate ceasefire’ and just 19 percent sympathising ‘more’ with Israel than Palestine, nowhere is this sentiment expressed in the so-called ‘free’ press. The papers pump out pro-Israel, pro-war propaganda, lies, and distortions, because that’s in the interests of their billionaire owners.

As home secretary, Suella Braverman attempted to ban pro-Palestinian demonstrations. The Commissioner of the Met Police has explained that the legal power to do that does not exist. But he stated that he would be in favour of Parliament giving the police such powers.

It is not merely the fact that we have a particularly right-wing government in Britain that accounts for this swathe of attacks on democratic rights. The same repression against pro-Palestine protests is being repeated in Germany, Austria, France, Switzerland, the US and elsewhere.

Whilst they principally target Muslims and pro-Palestine protesters today, the ruling class looks to the future with dread. They anticipate enormous class battles and revolutionary upheaval. And they are preparing by clamping down on democratic freedoms, by beefing up their means of repression, and by accustoming public opinion to repressive measures.

What has become clear is that, under capitalism, the right to freedom of speech exists for those wealthy enough to publish newspapers. And the right to freedom of assembly exists for those rich enough to own large buildings.

But for those without these means – and who have very little time to exercise these rights anyway, due to the interminable grind of working all day to make someone else rich – our ‘democratic rights’ are nice in theory, but extremely restricted in practice.

As with the Chartists of the 1840s, and the labour movement in the 1980s, the struggle for democratic rights is once again opening up as an arena for class struggle.

Workers’ democracy

Defending and demanding democratic rights by basing ourselves on the rising class struggle is the communist method.

We don’t appeal to democracy in the abstract. We’re for democratic rights – such as the right to speak, meet, and organise – as a means by which the working class can fight for its interests.

This means we’re not just for the defence of bourgeois democratic rights, but for the extension of these rights into the economic sphere: to establish workers’ democracy.

And this raises the class question – the question of ownership and control, within the economy and across society.

To secure real freedom of association for workers, for example, all the biggest buildings and meeting places should be placed under the democratic ownership and control of the working class.

To ensure academic freedoms and genuine freedom of speech on campuses, devoid of big business pressures, the running of educational institutions – such as universities – should be in the hands of staff and students.

Public transport must be taken out of the hands of profiteers, and placed under the democratic ownership and control of workers, so that people can travel freely to meetings and demonstrations.

To secure real freedom of the press, the mass media should be taken out of the hands of a tiny clique of oligarchs, who only publish what’s in their own interests. Instead, it should be placed under the democratic ownership and control of the working class, so that what people really think can be freely expressed in the papers and reflected on our screens.

In order that workers have time to prepare for and attend meetings, write for and read the press, and generally exercise their rights of freedom and association, the working day must be shortened.

Planning the economy – democratically in the interests of need instead of profit – would eliminate all the waste that comes with cartels, profiteering, and the burning out of workers by the capitalist class. That would immediately reduce the length of the working day and working week, allowing people to truly exercise their democratic rights.

Genuine freedom and equality is therefore not a question of abstract democracy, but of the struggle for socialism.

Mass movement

This struggle is not fought through liberal appeals to bourgeois democratic institutions, like Parliament or the courts, but by relying on the strength and struggle of the working class itself.

In 1972, it was a mass movement of organised workers that defeated the government’s attack on the right to strike. Tens of thousands marched to Pentonville prison, forcing the release of five dockers who had been imprisoned under a new oppressive law.

Examples like this are what the TUC should bear in mind when it meets tomorrow, 9 December, to discuss how the trade union movement should fight the government’s attacks on the right to strike.

The aim of the trade union movement should not simply be to resist the implementation of these Tory laws, being introduced on behalf of the bosses, but to smash them to pieces through militant mass action.

There is no force on earth that can stop the working class, when it is organised and mobilised; no repressive apparatus that can subdue workers, once they begin to move en masse.

The numerical balance of forces is massively in the working class’ favour. This bodes well for present and future battles around democratic rights. But numbers on their own aren’t enough.

What’s needed is a determined political party that can link the attacks on the right to strike with the suppression of democratic rights around the pro-Palestine movement; and which, in turn, can be linked with the cost-of-living crisis and the wider capitalist crisis that is bearing down on workers.

Unless these fights are tied together, and fought on the basis of working-class methods, nothing will be fundamentally solved. This is why a Revolutionary Communist Party is urgently needed. This is what we need to build.