Tensions are rife at the annual conference of the UCU, where union leaders are feeling the reverberations of the recent lecturers’ strike.

The first day of the UCU congress saw open war between the grassroots and the leadership. The union bureaucrats used every dirty tool at their disposal to shut down attempts to hold them accountable – upto and including a bizarre ‘wildcat strike’ that ended with the declaration of an official trade dispute against the UCU membership.

The drama began before the first motions were even heard. Chair and UCU President, Joanna de Groot, suspended business following a walkout by paid union officials and their supporters over whether to accept a late motion from the UCU branches at Sheffield and Bath. The motion expressed concern about the stitched-up ballot that ended the strike prematurely, criticising the leadership and calling for a democratic review of the union’s structures.

Wildcat strike against union democracy

The walkout meant the conference no longer had quorum. As a result, in scenes that recalled the farcical NUS conference shut-down in March, business was suspended for two-and a-half hours while a compromise (that removed the sharpest parts of the original motion) was reached in a private meeting. As a result, the first motion wasn’t heard until 3pm!

Paid union members (including general secretary Sally Hunt) – who are represented by Unite the Union – especially objected to motions 10 and 11, which respectively called for a declaration of no confidence in the leadership and a censure for their actions during the pensions dispute.

Unite issued a statement claiming that these motions unfairly attack members “without due process”, violating “employees’ dignity at work”. They warned that they would hold “immediate emergency meetings to consider [their] response” if the motions were debated. Hunt’s faction even organised a picket – at a trade union congress!

According to this warped logic, by exercising their democratic right to hold their union leaders to account, the membership are acting as ‘bosses’ – and are apparently unfairly victimising the ‘workers’, i.e. the UCU leadership!

Hunt began the conference quite confident in her position, given that members voted by a two-thirds majority to accept her rotten deal to kick the pensions dispute down the road. This is probably why the no-confidence and censure motions were accepted onto the congress agenda.

However, the delegates at congress are elected by the branches: they represent the most active layer of the membership, which remains furious at the treacherous, anti-democratic role Hunt played during the recent USS strike.

When it became apparent that the congress was not going their way, the leadership became desperate.

Bureaucrats bust their own congress

The NEC demanded a vote on whether to even hear motions 10 and 11, and the Unite-represented delegates threatened to walk out if they were debated – effectively holding the congress to ransom.

The NEC demanded a vote on whether to even hear motions 10 and 11, and the Unite-represented delegates threatened to walk out if they were debated – effectively holding the congress to ransom.

The vote was 123 FOR and 144 AGAINST withdrawing the motions. As promised, Hunt’s faction left the room, leading to a 30-minute suspension, during which Unite declared an official trade dispute against the highest decision-making body of the UCU.

In the end, the day’s business at congress was ended early. The NEC, motion proposers and Unite members will attempt to come to some arrangement before business resumes.

The ludicrous situation was summarised neatly by one UCU member, who said on Twitter that:

“a credible industrial strategy is being developed at UCU congress: unofficial walkouts and solidarity pickets. If only [the leadership would] apply this approach against the employers instead of their own freaking membership we might actually be able to save our pensions.”

In a way, a credible industrial strategy is being developed @ UCU Congress: unofficial walk outs & solidarity pickets. If only they’d apply this approach against the employers instead of their own freaking membership we might actually be able to save our pensions #UCU18 #UCU2018

— PerrierCommunist (@PerrierCommuni1) May 30, 2018

As the farce unfolded, social media was awash with infuriated UCU members decrying the leadership’s flagrant contempt for democracy, with many vowing to leave the union in protest.

Unite rank-and-file members, who have been betrayed by their own union bureaucracy in the past, also expressed their disgust at UCU members being denied their democratic rights. Anthony Johnson, a nurse and trade union activist, tweeted:

“Why the heck is there a Unite Picket at #UCU2018? Surely my union should be supporting the rights of rank and file UCU members to hold their leadership to account?”

Why the heck is there a Unite Picket at #UCU2018 surely my union should be supporting the rights of rank and file UCU members to hold their leadership to account?

— Anthony Johnson (@Ant8Johnson8) May 30, 2018

Dump the dead wood! Hunt must go!

This shameful turn of events plainly reveals that the ladies and gentlemen at the top of the union – all-too-eager to sit down for respectable negotiations with the bosses in Universities UK – are afraid of the militancy of their own members and are willing to use dirty bureaucratic tactics to silence dissent.

The UCU has come off the back of a powerful strike. Our union has acquired thousands of enthusiastic new members, eager to fight for an end to Tory attacks on the education sector. It could – and should – harness this momentum and reach out to students and other workers to unite and fight for socialism. Instead, the union leaders have reached out to other bureaucrats, pitting workers against one another to save their own hides!

We hope, when business resumes, delegates will take the opportunity to remove the wreckers at the top – replacing them with a leadership that is answerable to the democratic will of the membership.

We should not throw the baby out with the bathwater and abandon our union. Instead, we should ditch the dead wood at the top and stride forward with a radical programme for changing society.

UCU Congress: the strike showed our strength

Joe Attard, King’s College London UCU executive (personal capacity)

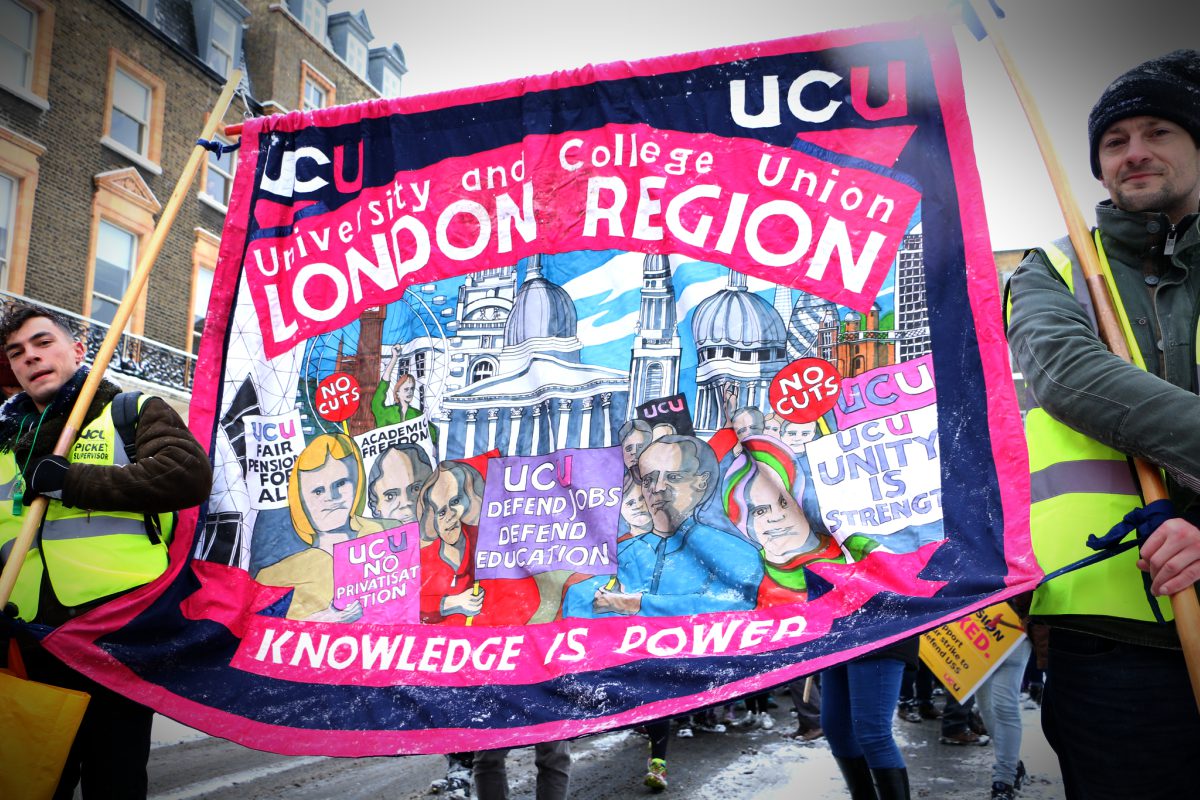

This year’s lecturers’ strike was the biggest and most militant industrial action ever taken by the University and Colleges Union (UCU). Over the course of four weeks, thousands of lecturers and casualised teaching staff downed tools in defence of their pensions. The strikers braved blizzards, threats from management and media slanders.

This year’s lecturers’ strike was the biggest and most militant industrial action ever taken by the University and Colleges Union (UCU). Over the course of four weeks, thousands of lecturers and casualised teaching staff downed tools in defence of their pensions. The strikers braved blizzards, threats from management and media slanders.

Against all odds, the bosses’ organisation (Universities UK) was forced back to the negotiating table. It was an inspiring period for our union, one that was sadly cut short before its full potential could be realised.

The dispute began after Universities UK (UUK) announced it would unilaterally transfer the main lecturers’ pension plan from a system of defined benefit to defined contribution. This means that, rather than receiving a reliable return, our pension payout would be weighed against the stock market.

This forced process of ‘de-risking’ was an attempt to plug a purported £7bn deficit in the USS (the Universal Superannuation Scheme), resulting from the low yield of government bonds after the 2008 recession. Once again, ordinary workers were being asked to shoulder the burden of a capitalist crisis we did not create.

This came after years of marketisation and casualisation within the HE and FE sectors (60 percent of staff are on precarious contracts), alongside a 15 percent pay-cut for academics over the last 10 years – all while vice-chancellors (whom the UUK represents) rewarded themselves with six-figure salaries. The attack on our pensions was the last straw.

Solidarity and support

In January, 88 percent of UCU members voted for strike action on a record 58 percent turnout, smashing the threshold established by the Tories’ draconian 2016 Trade Union Act.

In January, 88 percent of UCU members voted for strike action on a record 58 percent turnout, smashing the threshold established by the Tories’ draconian 2016 Trade Union Act.

As the strike dates approached, the Tory press did everything in its power to pit students against us. It was said that students would be hostages of an action in which they had no stake, paying through the nose for weeks of teaching they would never receive.

A few students launched petitions, which acquired thousands of signatures, demanding fee refunds for teaching lost to strike action. While some of these petitions were presented as acts of solidarity, targeting university management rather than lecturers, others explicitly criticised the strike – and all of them were a gift to management looking for ways to divide students from staff.

I’ve been on a few UCU strikes in my time: they are usually during the holidays and last a matter of days. Picket lines are poorly attended and easily-crossed, often by students who might well be sympathetic but simply had no idea we were striking. Given the dire straits of higher education, this is an indictment of our union leadership.

From day one of this year’s strikes, however, it was obvious this would not be business as usual. The picket lines were massive and the real mood of our students was shown by the huge numbers who respected the picket lines and the numbers that turned out in solidarity, attending teach-outs autonomously organised by striking staff. At my university, King’s College London, just 10 percent of classes went ahead during the strike.

The National Union of Students offered a statement of solidarity, and motions of support were passed by local student unions all over the country. Hundreds of students occupied universities to put further pressure on the bosses. Student solidarity was consistently reflected in national polls, which showed majority support for the UCU.

#NoCapitulation

This was a remarkable action. But much more could have been achieved had the union leadership connected our struggle with that of other public sector workers – escalating and politicising our strike, and turning it against the Tory government.

This was a remarkable action. But much more could have been achieved had the union leadership connected our struggle with that of other public sector workers – escalating and politicising our strike, and turning it against the Tory government.

Instead, Sally Hunt and co. were a brake on our action from day one. They were dragged along by the grassroots at every turn. They tried to end the strike in its third week by imposing a toxic deal that would have fulfilled none of our demands and seen us work for free to cover lost teaching hours.

Only a rapid, grassroots response prevented this stitch-up from going ahead, with angry lecturers nearly storming the UCU HQ in London!

In the end, our action forced the UUK to give ground in the form of an offer to re-evaluate the risk contained in USS with input from the UCU on an “independent panel”. However, we were given no more assurance than a set-up “broadly comparable” to the current one, which could mean literally anything. There is always the danger the bosses will kick the can down the road and try to impose another pension attack in a year’s time when the panel publishes its findings.

While the majority of branches were in favour of either revising the offer or insisting on a no cuts, “no detriment” clause, Hunt went over our heads to present the offer as an ultimatum: take it or leave it. She spooked the membership by claiming rejection would mean no deal at all.

This, coupled with a certain exhaustion after a month of strikes, and with the exam period approaching (in which pickets are less effective, as there are few classes) meant the deal was accepted with a two-thirds majority.

Connect the dots

The most militant layers of our membership built up goodwill with students by connecting our dispute to a wider struggle against marketisation and forging links with other university workers (cleaners, support staff and so on) who have also been hit by pay cuts and casualisation.

From the beginning, we needed to connect our strike to a general, political struggle against the Tories’ reactionary education policies, which the UUK merely reflects. We could easily have connected our strike to the fight for free education and reached out to colleagues in FE who are currently striking over pay.

Beyond that, we could have encouraged nurses, doctors, teachers and so on to organise for coordinated action against the root of all attacks on the public sector: the capitalist system and its representatives in parliament.

As ever, our leadership was not interested in fighting for fundamental change, just winning leverage for respectable negotiation with the bosses.

Our union has changed drastically as a result of our strike. We have grown by 40 percent, and a new layer of extremely radical members (many of them young casuals) have had a taste of our collective strength.

New academics stand to lose the most from cuts to the USS and from capitalist attacks on the education sector more generally. These members must make their voices heard at congress.

We need a radical, socialist programme – through which we can connect with other workers and students in a general fight to transform society – and a leadership willing to carry it out.