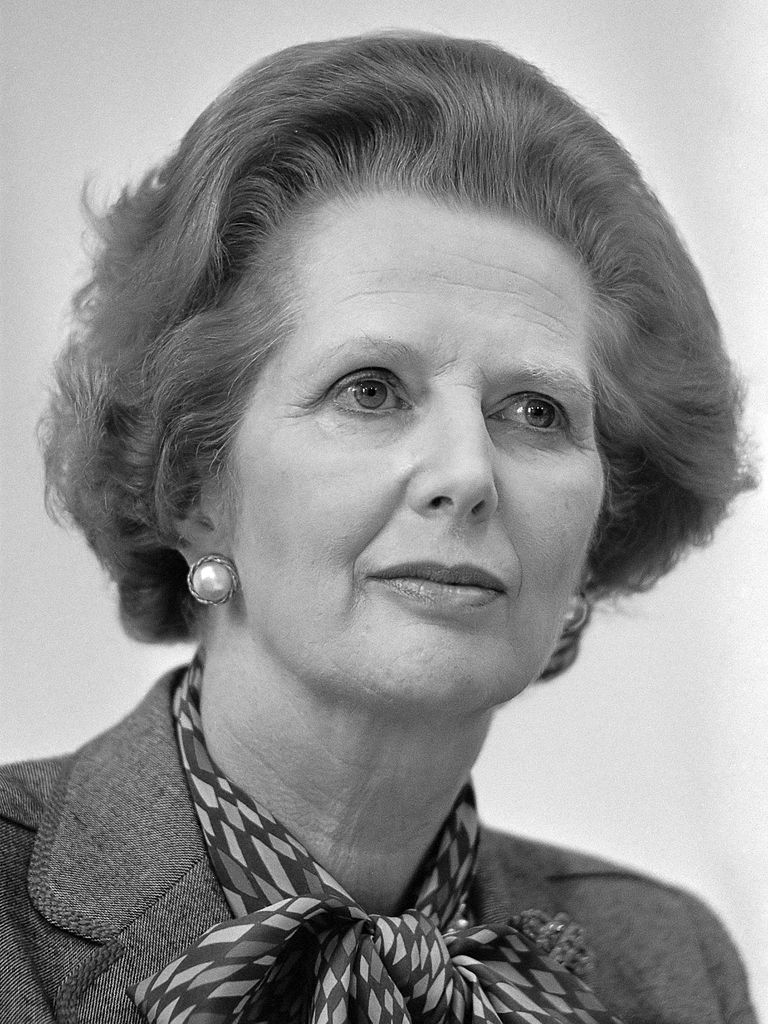

The Thatcher government, elected in 1979, prepared to attack workers’ pay, terms and conditions, and implement a massive cuts and privatisation programme. This made confrontation with the trade union movement inevitable.

Stung by forced retreats from attacks on the miners and dockers’ unions, Thatcher hoped the civil service unions would prove an easy touch. Her government suspended a national pay agreement; withheld a pay comparability report; and, with inflation at 15%, imposed a 6% pay limit.

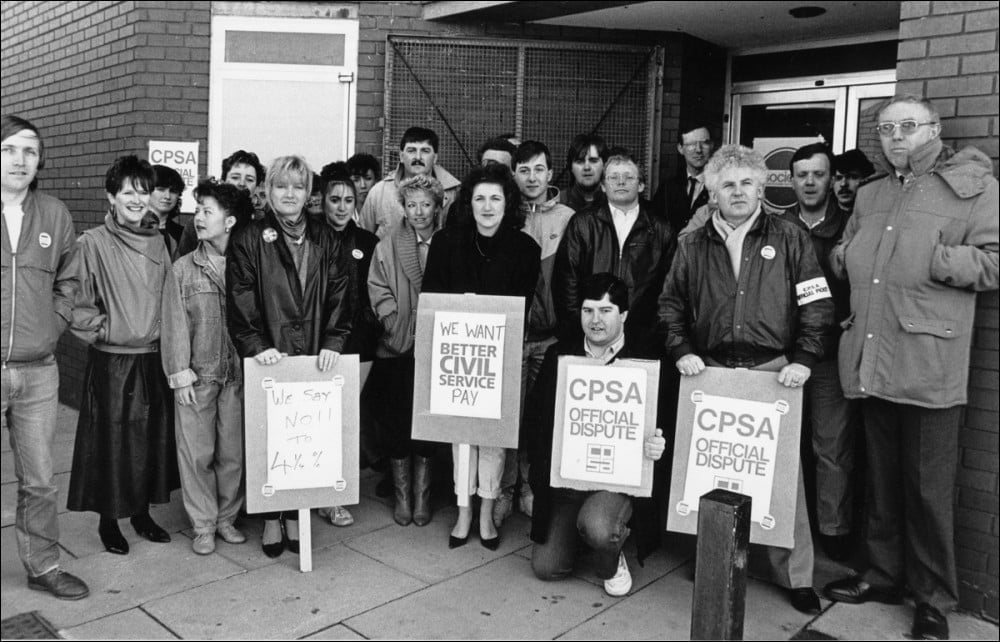

The Tory government’s actions were encouraged by a right-wing ‘moderate’ national executive committee (NEC) of the CPSA (Civil and Public Services Association – a predecessor union to PCS), which had acquiesced with a new technology programme that would cost tens of thousands of job losses.

Anachronistic press stereotypes of the ‘pen-pusher / brolly brigade’ were belied by the social composition of the civil service workforce. De-industrialisation along with post-war expansion of public services saw working-class youth – mainly female – enter the civil service in great numbers, instead of finding work in factories and mills. This drove up union membership and militancy.

The founding of an open CPSA Broad Left – with the Militant Tendency playing a leading role – led to the emergence of an organised cadre of socialist activists whose influence in workplaces throughout Britain was steadily increasing.

Activists and members demanded ‘effective action’, and a joint, coordinated response from all nine civil service trade unions under the Council of Civil Service Union (CCSU).

This body represented over 500,000 workers in central government. This included civil servants working in defence, unemployment benefit offices, jobcentres, skill centres, social security, passports, taxation, revenue and customs, courts, immigration and more.

Battle lines drawn

A CPSA special pay conference, held in January 1981, agreed a 15% pay demand and set out a strategy to achieve it:

“No section of the membership should be excluded: selective strike action in the most effective areas e.g., customs, immigration and Civil Aviation Authority; one-day strike of all members; consultation with other civil service unions to set up ‘all unions’ campaign committees; a strike levy; regular information bulletins; industrial action to be escalated as and when circumstances require.”

The dispute began with a one-day civil-service-wide strike. This was followed by long-term selective action, involving as little as 5,000 workers in key areas, accompanied by short-term ‘guerrilla’ action – such as walkouts, work to rules, go-slows etc.

Such tactics had been successfully applied in previous campaigns like the air traffic controllers and British Telecom computer centre disputes.

But the Tories were prepared, and were determined to stand firm against the CCSU strategy of relying on a small group of workers to win disputes, with strike pay and levies from the majority of the membership.

CPSA Broad Left similarly understood the limitations of such a strategy, and its leaders – like Kevin Roddy – argued that members must be prepared for escalation as a route to all-out action if necessary.

Establishment shaken

National one-day strikes paralysed central government services, including customs, immigration, ports, airports, and passports. Even Downing Street itself was picketed. Postal workers and prison officers refused to cross picket lines. These strikes were solidly supported, particularly in large workplaces like Longbenton and Washington child benefit centre.

600 walked out at the army pay unit, disrupting contract payments for the British army. In Southampton, holiday-makers walked through empty customs stands; manual workers were sent home from the Portsmouth Naval Dockyard when supervisors struck; driving tests were cancelled; Gatwick and Heathrow airports were shut; and in Manchester, air traffic engineers took their first ever strike action, organising joint picket lines with civil servants.

A walkout at the health physics department “seriously impair(ed) the re-fitting of new nuclear submarines in dry dock”. A silent protest held outside the Admiral Superintendent’s office brought workers’ discontent and anger to the door of the ‘brass-hats’.

Selective action was even taken by workers at the Government Communications Head-Quarters (GCHQ) in Cheltenham – a key element of US/UK intelligence gathering. This “threat to national security” directly led to the subsequent union ban there.

Threats to bring in military personnel to strike-break led to pledges of solidarity from the Transport and General Workers Union, which organised industrial staff.

Action in supposedly no-go areas like the Ministry of Defence and the courts shook the establishment. This provoked an hysterical press reaction. Strikers were accused of “putting personal gain before the defence of the realm”, and being “parasitical and without public conscience”.

By April, government income was halved by selective strike action in Inland Revenue and Value Added Tax computer centres, and it was reported that £5.5 billion had been withheld from the Treasury. Government borrowing went up threefold, and Tory Chancellor Geoffrey Howe conceded “action was doing substantial damage to government finances”.

Demands for escalation

Pay increases were due on 1 April, but the NEC failed to coordinate action and protests nationally. They even urged members to stay at work and make financial contributions.

Local strike committees responded by organising protests and unofficial walk-outs. But the question activists and members were asking was: what would it take to win?

The CPSA conference in May overwhelmingly supported a strategy involving: the closure of ports and airports; indefinite action by passport office staff; continuation of selective action; and an increased strike fund levy – all with a planned move to a five-day strike if these measures failed, and as a stepping-stone to all-out action.

Serious debate took place over strategy and tactics. 80,000 workers from the Departments of Employment (DE) and Health and Social Security (DHSS) had not been brought into selective action from the beginning of the dispute. At the sharp end of service delivery to some of the poorest and most marginalised sections of society, these workers were amongst the most militant in the civil service.

Activists had forged strong links with unemployed workers organisations and unemployed workers’ centres. The press – who regularly denounced benefit claimants – attempted to stoke division between workers and benefit claimants by raising ‘concerns’ over the impact strikes would have. The aim was to keep these workers to the sidelines of the dispute.

Activists disagreed on whether members should issue emergency benefit payment to claimants – a tactic designed to obviate accusations the union was hurting the most vulnerable sections of its own class.

This tactic would have strengthened solidarity; unemployed workers generally supported the union campaign. But in administering benefits, the union would be implementing a time-honoured principle of the trade union movement: only striking workers should determine what services – on an emergency or humanitarian basis – could operate under union control.

Others argued this would be ‘scabbing on our own dispute’ and no consensus was reached. Action did take place in DE and DHSS offices. But this was not generalised, and was often only in response to suspensions.

Weakness and hesitation

Despite demands for escalation, the CCSU leadership continued with the same strategy. This encouraged the Tories to sit tight.

Union leaders had begun to sue for peace in secret talks. These took place behind the backs of members, and even union executives. In these talks, the leadership agreed to a ballot on any new offer, however poor it may be. In television interviews, these same leaders talked about an ‘inevitable return to work’.

The Tories offered 7% on a ‘take it or leave it’ basis. But members rejected this insult. The Inland Revenue Staff Federation and CPSA both voted for all-out action. This was a watershed development in civil service trade unionism. But CCSU persisted with selective action.

Socialist full-time officer John Macreadie’s call at the NEC for CPSA to take unilateral all-out action was ruled out of order by the acting president, who insisted that the power to call action had been “handed over to CCSU”.

Having demoralised members by refusing to build for an achievable victory, these leaders – as their type always does – blamed members for not supporting the strike. Instead, they engineered a return to work.

Struggle for a fighting union

Although ending in defeat, the strike transformed and radicalised civil service trade unionism. It was a major milestone in transforming CPSA from a ‘staff association’ into a fighting trade union – with one of the most militant rank-and-file socialist broad lefts in the movement.

Thatcher’s attacks continued, and the right-wing leadership’s refusal to organise effective national action led to serious setbacks, like the abolition of national pay bargaining, and a ‘bonfire of agreements’ of terms and conditions. But even the right-wing could not prevent civil service workers fighting back.

Under membership pressure, they were forced to sanction a series of local and group strikes – some of a very fierce and extended character. This includes the year-long Newcastle shift-workers dispute; three-month Easterhouse staffing dispute; six-month Caerphilly DHSS dispute; and the year-long screens dispute.

The right wing witch-hunted individuals and branches, most viciously at Newcastle Central Office. And they collaborated with management in victimising and sacking union reps, as in the Bedminster jobcentre dispute.

But activists and members fought back against these attacks, demanding union democracy, adherence of the NEC to conference policy, and a members-led union, capable of fighting back against attacks on them.

Following the strike, long years of struggle saw the left win the leadership of PCS. This laid the foundation for building a member-led, militant, and democratic trade union – one that has been a ‘beacon of resistance’ for the past two decades.