Forty years ago this month, in a small school hut in La Higuera, Bolivia, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara was brutally executed by the Bolivian army.

Forty years ago this month, in a small school hut in La Higuera, Bolivia, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara was brutally executed by the Bolivian army.

Since Che’s death, the popular media have tried to assimilate his image and turn it into a harmless symbol. They have, however, not succeeded in burying the memory of Che, just as they have not managed to solve the problems of poverty and destitution in the third world.

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina in 1928. His parents were relatively well off and were able to pay for a good education. In 1948 he went to study medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. As a break from his studies, Alberto Granado and Che embarked on a motorbike journey across South America. It would be during this trip that Che would witness the grinding poverty that is endemic to the continent.

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina in 1928. His parents were relatively well off and were able to pay for a good education. In 1948 he went to study medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. As a break from his studies, Alberto Granado and Che embarked on a motorbike journey across South America. It would be during this trip that Che would witness the grinding poverty that is endemic to the continent.

Returning to Argentina, in 1953 he graduated from university, and soon set out on another trip. Following the west coast, he arrived in Guatemala City. The experience of Guatemala in 1954 had a strong influence on his thinking. Jacobo Arbenz had attempted to carry out a modest agrarian reform and nationalising the 3 million acres of the United Fruit Company. This was a reform that the US could not stomach, and the CIA set about organising a military overthrow of Arbenz.

At that time Che commented that "Without a doubt Colonel Arbenz is a guy with guts, and is ready to die in his post if necessary". The CIA backed-paramilitaries led by Castillo Armas, together with the reactionary media and Catholic Church, stepped up their assault. Che described the atmosphere as a "terrible shower of cold water" falling over the people. Arbenz relied on the old state apparatus to crush the rebellion. Sections of the army demanded the President’s resignation.

In Guatemala, Che saw the limits of parliamentarism, which left a strong impression on his thinking. Any peaceful attempt at meaningful reforms would be met with armed hostility from the USA. He was now sure that only armed revolutionary struggle could guarantee against US intervention and provide the means to success.

Like thousands of other leftists fleeing Guatemala, Che went to Mexico. There he was introduced to Fidel Castro. Fidel was a leader of the July 26 Movement – so named after a failed attack on the Moncada barracks in Cuba, as part of an attempt to oust the dictator Fulgencio Batista. Coming from the left-wing of the anti-imperialist democratic Partido Ortodoxo, Fidel Castro was already a well-known revolutionary leader. After a nightlong discussion, Che agreed to join Fidel’s planned invasion and guerrilla war against Batista. For Che, this undertaking would prove the viability of guerrilla warfare in the underdeveloped third world.

Like thousands of other leftists fleeing Guatemala, Che went to Mexico. There he was introduced to Fidel Castro. Fidel was a leader of the July 26 Movement – so named after a failed attack on the Moncada barracks in Cuba, as part of an attempt to oust the dictator Fulgencio Batista. Coming from the left-wing of the anti-imperialist democratic Partido Ortodoxo, Fidel Castro was already a well-known revolutionary leader. After a nightlong discussion, Che agreed to join Fidel’s planned invasion and guerrilla war against Batista. For Che, this undertaking would prove the viability of guerrilla warfare in the underdeveloped third world.

Guerrilla war

The Communist Party in Cuba, the Popular Socialist Party (PSP) initially did not support the July 26 Movement, but only jumped on the bandwagon at the last moment.

Unfortunately, the beginnings of the guerrilla war did not go well. Out of 82 guerrillas in the initial attack, only 15 survived and sought refuge in the mountains of Sierra Maestra. After a period, a number of successful raids allowed the rebels to establish a liberated zone. While massively outnumbered by Batista’s standing army, what was remarkable was its ineffectiveness; numbering around 35,000 in strength it was unable to defeat the guerrillas who at times numbered less than 200 men. This was a reflection of the decay of the Batista dictatorship. The last serious attempt to crush the rebel army was "la Ofensiva", where some 12,000 demoralised soldiers failed to defeat the guerrillas.

During the struggle Che had been promoted from medic to Commandante, in command of his own column. Within the liberated zone he established Radio Rebelde – a lesson learnt from Guatemala where the media had been in the hands of the ruling class. He had gained the respect of the rebel fighters, and was known for his tight discipline. As the tide turned in Castro’s favour, Che led his column to the city of Santa Clara, the last outpost on the road to Havana. The rebels were greeted on their way by cheering peasants, and military outposts were surrendered without incident.

During the struggle Che had been promoted from medic to Commandante, in command of his own column. Within the liberated zone he established Radio Rebelde – a lesson learnt from Guatemala where the media had been in the hands of the ruling class. He had gained the respect of the rebel fighters, and was known for his tight discipline. As the tide turned in Castro’s favour, Che led his column to the city of Santa Clara, the last outpost on the road to Havana. The rebels were greeted on their way by cheering peasants, and military outposts were surrendered without incident.

With the collapse of the regime, the power vacuum in Cuba was not filled with any urban movement, a weakness of the tactic of guerrillaism. On December 31, 1958 Batista fled the country, but the guerrillas were still outside of Havana. The ruling class attempted to prop up the regime with a new president. But Fidel made an appeal for a general strike, and the response was solid – Havana was paralysed for a week. This allowed the victorious rebel army to enter Havana and for Cuba to determine its own future.

Reforms

Che Guevara, a key leader of the revolution, took on at different times a number of ministries within the new government. The government introduced a number of measures, such as a land reform which limited the size of holdings and outlawed foreign ownership of land. These reforms were seen by Washington with alarm. Throughout 1959 the USA became more hostile to the new Cuban government. Fidel reacted by replacing more liberals in the government with communists. Washington placed an embargo on Cuba in an attempt to bring Castro to his knees. However, this provoked the Cuban government which proceeded to nationalise US companies. By the end of 1961 Cuba abolished capitalism and declared itself a socialist republic.

On the basis of his experience and the victory of the Cuban Revolution, Che generalised the idea of guerrilla struggle as a means of carrying out the socialist revolution. This theory became known as Focalism. The idea was that a small foco, a vanguard group of guerrilla fighters could kick-start the revolution. This would be a focal point for the population as a whole, bolstering their morale for a popular uprising, while beginning the revolutionary struggle in the countryside themselves.

Using this strategy, Che attempted to export this Cuban model abroad, participating personally in the Congo and Bolivia.

Using this strategy, Che attempted to export this Cuban model abroad, participating personally in the Congo and Bolivia.

Despite the relationship now between Cuba and the Moscow bureaucracy, the Communist Parties of Latin America, ever loyal to Moscow, were wedded to the policy of "peaceful coexistence" and did not want to upset their alliance with "progressive" bourgeois parties. "Peaceful co-existence" was a policy devised by the Russian bureaucracy during the Cold war to come to an accommodation with imperialism. Such a policy was aimed at preserving a status quo between the two social systems. Clearly any policy aimed at spreading socialist revolution was an anathema to them. Che completely rejected "peaceful coexistence". "The socialist countries have the moral duty of liquidating their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West", he wrote. Che was an internationalist, who could see the limits of "socialism in one country", and so used his influence to organise guerrilla warfare in Latin America and elsewhere.

With the prestige of October 1917 behind them, internationally the Communist Parties were a pole of attraction for many workers and peasants. They had come to the aid of the Cuban Revolution. Nevertheless, Che had witnessed the weaknesses of the Communist Party in Guatemala and was deeply opposed to the conservative stance of the Russian Stalinists.

The Stalinists internationally were wedded to the "two-stage" theory, whereby the working class and other "progressive forces" would concentrate on the first national-democratic stage and only much later would the struggle open up for socialism. The first stage would mean an alliance of the workers with the local capitalist class. The problem being that in the third world there was no independent revolutionary national bourgeoisie. In fact, the bourgeoisie was linked to the landowners, subservient to imperialism, and played a counter-revolutionary role. The "two-stage" policy would lead to disaster in one country after another.

Alliance

A serious revolutionary programme would have looked towards the alliance of workers and peasants, and sought to link the tasks of the "national-democratic" revolution with the socialist transformation of society. This, in fact, was the very lesson of the successful Russian Revolution in 1917.

In the preface to his Diary from his time in the Congo, Che opens with the words: "This is the history of a failure." He went to the Congo to try and instil in the revolutionary fighters his idea of the foco and socialist revolution. However, the army was able to monitor his communications, and at every attempted offensive they crushed the guerrillas. This, combined with the incompetence of the guerrilla forces, led to the withdrawal of the Cuban expedition after seven months, disillusioned with their experience.

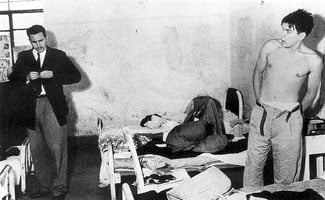

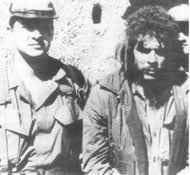

Che’s next attempt to promote guerrilla warfare was in Bolivia. Once again, this proved to be disastrous. He set out with a small band of guerrillas with no support from the Bolivian Communist Party, loyal as ever to Moscow. Bolivia, as the poorest country in South America, and with a powerful working class employed in its mining industry, certainly had potential for revolution. Land had been purchased for the setting up of a guerrilla base to train and acclimatise recruits. After a number of small initial successes in the area, Che’s group began to run into sever problems. The guerrillas had failed to establish any roots amongst the peasants. Isolated and exhausted, Che was flanked by the Bolivian army, trained by US Army Special Forces, and under the direction of the CIA. Eventually Che was captured by the Bolivian army, and taken to a schoolhouse. He was shot repeatedly below the neck to make it appear his death was from combat wounds, not an execution.

Che’s next attempt to promote guerrilla warfare was in Bolivia. Once again, this proved to be disastrous. He set out with a small band of guerrillas with no support from the Bolivian Communist Party, loyal as ever to Moscow. Bolivia, as the poorest country in South America, and with a powerful working class employed in its mining industry, certainly had potential for revolution. Land had been purchased for the setting up of a guerrilla base to train and acclimatise recruits. After a number of small initial successes in the area, Che’s group began to run into sever problems. The guerrillas had failed to establish any roots amongst the peasants. Isolated and exhausted, Che was flanked by the Bolivian army, trained by US Army Special Forces, and under the direction of the CIA. Eventually Che was captured by the Bolivian army, and taken to a schoolhouse. He was shot repeatedly below the neck to make it appear his death was from combat wounds, not an execution.

Class fighter

Che should be remembered as a heroic class fighter, someone completely dedicated to the cause of international socialist revolution. His dream today still goes unrealised. However, we must learn the lessons of the failures of guerrillaism. While the peasantry can play an important role, the leading role of the socialist revolution falls to the working class as in the Russian Revolution. Only they can develop a socialist consciousness and bring about a real workers’ democracy.

Che should be remembered as a heroic class fighter, someone completely dedicated to the cause of international socialist revolution. His dream today still goes unrealised. However, we must learn the lessons of the failures of guerrillaism. While the peasantry can play an important role, the leading role of the socialist revolution falls to the working class as in the Russian Revolution. Only they can develop a socialist consciousness and bring about a real workers’ democracy.

The prospect of socialist revolution is stronger today. The Venezuelan revolution stands out as a beacon to the whole of Latin America, with its mass support amongst the workers and urban and rural poor. This mass movement stands on firmer ground than any guerrilla expedition. Cuba, under the merciless pressure of US imperialism, has weathered the collapse of the Soviet Union, now looks to the Venezuelan Revolution to break its isolation.

Che grew steadily disillusioned with Stalinism and sharply criticised the conservative role of the Russian bureaucracy. Increasingly he searched for new ideas and a new way forward. It was not for nothing that when he was killed he had in his nap sack a copy of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution.

Che grew steadily disillusioned with Stalinism and sharply criticised the conservative role of the Russian bureaucracy. Increasingly he searched for new ideas and a new way forward. It was not for nothing that when he was killed he had in his nap sack a copy of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution.