Leon Trotsky asked British Marxists in particular to study the 1926 General Strike, the English Revolution of the 1640s and the Chartist movement of the 19th Century. “The era of Chartism is immortal in that over the course of a decade it gives us in condensed and diagrammatic form the whole gamut of proletarian struggle,” explained Trotsky.

The British working class of the 19th Century emerged as a force out of the furnace of the Industrial Revolution. Savagely exploited, they turned to collective class action and trade unionism, which was soon declared illegal and mercilessly driven underground by the bosses’ state.

Following the “Great Betrayal” of the so-called Reform Act of 1832, where workers were denied the vote, they started to draw political lessons.

New leaders began to emerge to fight for working-class political rights and above all the right to vote. In June 1836, the London Working Men’s Association was formed, which drew up what was to become the “People’s Charter,” a six-point programme for political change. From such modest beginnings would emerge the mass ranks of the Chartists.

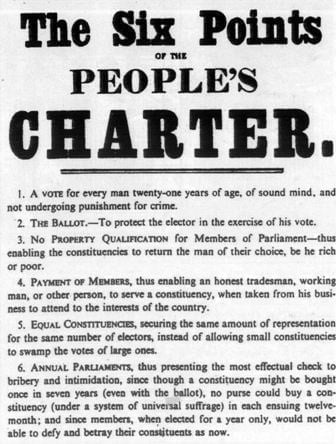

The Charter called for:

- A VOTE for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for crime.

- THE SECRET BALLOT to protect the electors in the exercise of their vote.

- NO PROPERTY QUALIFICATION for members of Parliament – thus enabling the constituencies to return the person of their choice, whether rich or poor.

- PAYMENT OF MEMBERS, “thus enabling an honest tradesman, working man, or other person, to serve a constituency.”

- EQUAL CONSTITUENCIES, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors – instead of allowing rotten boroughs.

- ANNUAL PARLIAMENTS, “thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation.”

In the north of England, a mass movement was emerging against the new Poor Law, in opposition to child labour and demanding new factory legislation. The launch of the Charter quickly became a focal point for this growing discontent. It was in the poorest parts of Britain that the Charter and the Chartists would advance the most.

In May 1837, a rally in West Riding took place attended by 250,000 people to hear Chartist leaders Richard Oastler and the Reverend J.R. Stephens. Such figures were detested by the privileged classes but worshipped by the workers. Oastler was affectionately known as “the king of the factory children.” Stephens proclaimed that the ownership deeds of every mill were “written in letters of blood on every brick and stone in the factory.”

However, Chartism’s most well-known and undisputed leader was a fiery Irishman called Feargus O’Connor, a fervent supporter of Irish rebellion.

Peace and force

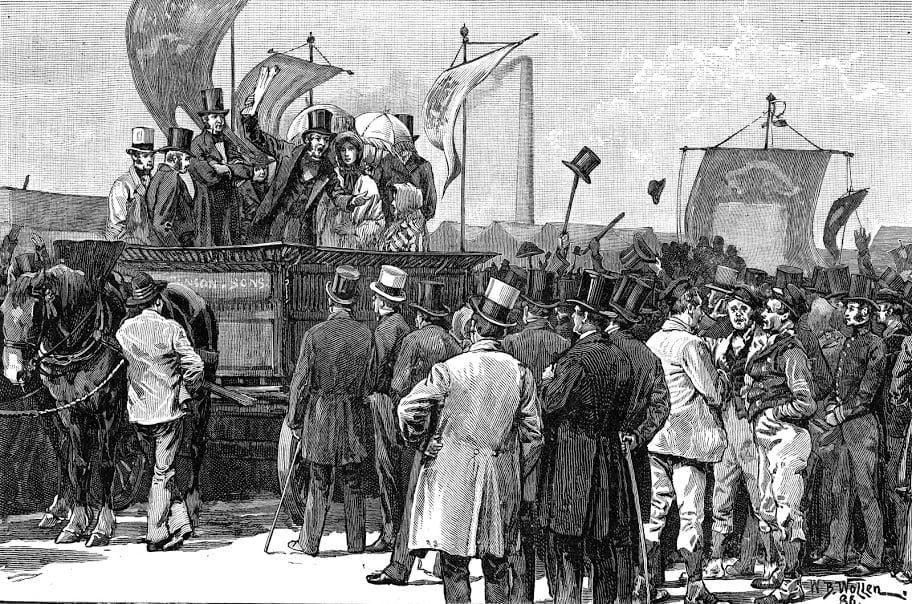

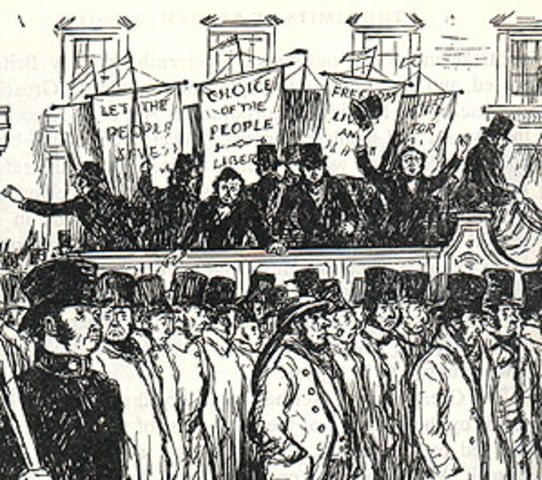

Chartism grew feverishly in 1837 and 1838, with mass meetings up and down the country. “The masses of the working men marched everywhere in serried columns, accompanied by bands and standard bearers to the places of assembly”, wrote the historian Max Beer. “Mass meetings were held in all the industrial centres… at which Stephens and O’Connor inflamed the masses with their speeches.”

Chartism grew feverishly in 1837 and 1838, with mass meetings up and down the country. “The masses of the working men marched everywhere in serried columns, accompanied by bands and standard bearers to the places of assembly”, wrote the historian Max Beer. “Mass meetings were held in all the industrial centres… at which Stephens and O’Connor inflamed the masses with their speeches.”

Chartist newspapers were also launched, such as the Northern Star. In early 1838, a national petition to parliament was drawn up and quickly rallied millions to the cause. “The excitement spread rapidly in all directions,” stated the 19th century social reformer Francis Place.

The idea arose of calling a National Convention (a term deliberately taken from the French Revolution) and would be regarded by many as a legitimate alternative parliament to the corrupt House of Commons.

However, sharp differences arose over how the aims of the Charter would be achieved. These divisions were expressed in the differences between the advocates of “moral force” and those who advocated “physical force.”

The former insisted that the National Convention was to simply promote the Charter to the Whig government by moral persuasion, whereas the “physical force” Chartists regarded the Convention as a rival form of government. The Northern Chartists, based upon the most downtrodden sections of the working class, were the most enthusiastic supporters of “physical force.” A huge gulf separated the two wings, a forerunner of the division between reformism and revolution.

“If peace gives law, then I am for order; but if peace giveth not law, then I am for war to the knife”, concluded Feargus O’Connor. Stephens, on the other hand, exclaimed: “I tell the rich to make their wills. The people are with us; the soldiers are not against us. The working men have produced all the wealth and they are miserable… If he has it not he has a right to come down on the rich until he gets it.”

The Chartist movement managed to hold together around the compromise formula, “peacefully if we may, forcibly if we must”. Nevertheless, there was no hiding the social-revolutionary aim of Chartism. The Northern Star proclaimed: “Socialism and Chartism pursue the same aims, they only differ in their methods.”

The Charter was clearly a means to an end, not an end in itself. According to Reverend Stephens, “This question of universal suffrage is a knife and fork question… if any man should ask me what I mean by universal suffrage I should reply: that every working man in the land has the right to have a good coat on his back, a comfortable abode in which to shelter himself and his family, a good dinner upon his table, and no more work than is necessary to keep him in good health, and so much wages for his work as should keep him in plenty and afford him the enjoyment of all the blessings of life, which a reasonable man could desire…”

A Soviet in embryo

The Convention assembled in London on 4th February 1839 amid wild enthusiasm and lasted with a few interruptions until 14th September. It was a working class Parliament – an embryo Soviet – which adopted, among other things, a resolution establishing “the right of the people of this country to possess arms” and to turn their back on “the hypocritical Whigs and the tyrannical Tories.” Chartism was certainly a class-conscious movement.

The Chartist Petition was launched with a series of demonstrations and rallies as the Convention moved north to Birmingham to be greeted by 50,000 workers.

On 21st May, more than 200,000 took part in a massive demonstration in Glasgow, followed by mass meetings in Newcastle (80,000), Birmingham (200,000), Manchester (300,000), Bradford (100,000), Sheffield, Bristol and London.

What if Parliament turned down the Charter? Many Chartists raised the idea of a month-long general strike, which was agreed upon. A left soon crystalised amongst the Chartists, which concluded that an insurrection was needed. The idea took hold and in Lancashire and Wales numerous Chartists obtained pikes and muskets. In other districts, workers engaged in military exercises.

On 29th April, the Welsh rose in revolt in Llanidloes but it was abortive and arrests followed. Despite appeals for calm, every day witnessed a further acquisition of weapons. William Benbow’s pamphlet on the general strike (the National Holiday or “sacred month”) and Francis Maceroni’s book on street fighting enjoyed phenomenal sales.

At the Convention, John Taylor declared “The people have got muskets, but they require bayonets in order to be able to resist cavalry charges. I move that the Convention issue, without delay, a request to the country at large to withdraw all the moneys from all banks or from persons hostile to the People’s Charter; to convert all paper money into gold; to abstain from all excisable articles of luxury; to commence exclusive dealings, prepare arms; and that the members of the Convention meet on 15th July for the express purpose of appointing a day when the sacred month or national holiday should commence.” Feargus O’Connor seconded the motion. Others intervened calling for an organisation like the United Irishmen. “Such an organisation is necessary. If the Government Peterloo’d the people, we should Moscow the country.”

The government acted to curtail the movement by sending troops to occupy Birmingham, arresting the Chartist leaders.

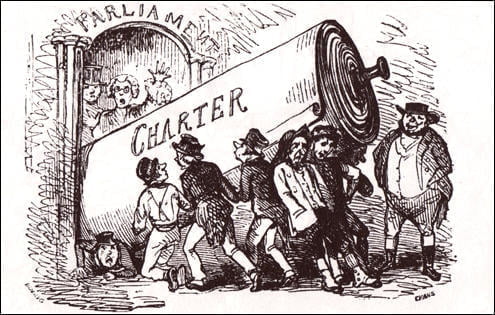

On 8th July, the Chartist Convention moved back to London as the second reading of the Petition, containing 1,280,000 signatures, was taking place in a few days. The Petition had been carried in a giant procession and presented to Parliament. In the Chamber, Lord John Russell warned that the adoption of the six-point Charter would mean the confiscation of all private property. Disraeli warned of a social insurrection.

A hostile House of Commons overwhelmingly rejected the Petition by 46 votes to 235 votes. On receiving news of the rejection, the mood within the Chartist Convention again reached fever pitch and shifted towards the use of “physical force.”

The moral argument had been tried and failed. Consequently, delegates set a date of 12th August for the start of a general strike to secure their demands. They launched an appeal calling on trade unions to “co-operate as united bodies with their more distressed brethren in making a grand moral demonstration on the 12th.”

Many believed that the strike was simply the prelude to an insurrection. “The sacred month”, explained Moir from Scotland, “is in fact nothing more nor less than the commencement of a revolution.”

The ruling class were not slow to react against this threat. The Convention itself had been subject to “desertion, absence, and arbitrary arrests”, which had depleted their ranks.

Given the difficulties, there were doubts about the effectiveness of the strike given the general distress at the time. In the end, the Convention decided unanimously to reduce the number of days but then temporarily abandoned the strike. The government then stepped in anyway and arrested 130 Chartist leaders.

Insurrection

With the road blocked to a peaceful solution, the Chartists looked towards an insurrection. Delegates Taylor, Frost, Cardo, Bussey, Burns and Lowery met in secret to prepare an armed uprising. Major Beniowski was sent to Wales as a military instructor, while retired noncommissioned officers were appointed in some towns in the North and Midlands to drill the workers. The country was divided into districts, with groups of 10, 100 and 1,000 with leaders and captains.

With the road blocked to a peaceful solution, the Chartists looked towards an insurrection. Delegates Taylor, Frost, Cardo, Bussey, Burns and Lowery met in secret to prepare an armed uprising. Major Beniowski was sent to Wales as a military instructor, while retired noncommissioned officers were appointed in some towns in the North and Midlands to drill the workers. The country was divided into districts, with groups of 10, 100 and 1,000 with leaders and captains.

The industrial valleys of South Wales were a hotbed of Chartism. In May 1839, the first “Rebecca Riots” broke out, where mobs of workers, with blackened faces and dressed in women’s clothes, destroyed the hated road tollgates. “The South Wales coalfield is the most terrifying part of the kingdom,” warned Home Secretary Viscount Melbourne.

This arrest of Henry Vincent, a leading Welsh Chartist, became a focal point for the insurrection. John Frost, another leader who was in close contact with the “physical force” leaders, decided to take the initiative into his hands to release him.

On 4th November 1839, Frost and his insurgents marched on Newport with three divisions armed with guns, pistols, coal mandrils and clubs and led by colliers, intending to rescue Vincent from a Newport prison and seize the town. They believed that his release would signal a large-scale insurrection throughout the country. Zephaniah Williams planned to set up a British Republic, while others hoped for the establishment of a Chartist Government, with John Frost as its president.

However, Frost was no military leader and only a few thousand men actually entered the town. The inevitable encounter with government troops, hiding inside the Westgate Hotel, ended in a bloodbath with 30 dead and the arrest of the South Wales’ leadership; among them, John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and William Jones. They were tried by the authorities and sentenced to be hanged. These courageous men were all prepared to die for the Charter and the cause of the working class. George Shell, a 19-year old who was shot dead at Westgate, wrote a note to his parents before joining the insurrection:

“I shall this night be engaged in a struggle for freedom, and should it please God to spare my life I shall see you soon; but if not, grieve not for me, I shall fall in a noble cause. My tools are at Mr Cecil’s, and likewise my clothes.”

Despite their bravery, the South Wales insurrection found itself isolated when the north of the country – due to a lack of serious preparation – failed to respond. There were revolts in Sheffield and Bradford but these remained isolated.

After mass protests, involving a petition signed by two million people, the death sentences against those arrested at Newport were commuted to transportation for life to Van Diemen’s Land, Tasmania.

Wholesale arrests followed which served to decapitate the Chartist movement. By the end of June 1840, at least 500 Chartists were incarcerated in prisons. The heroic Newport uprising served to mark the end of the first phase of Chartism.

With the release in 1841 of Feargus O’Connor and other Chartist leaders from prison, the agitation for the Charter was again revived. “Our movement is a labour movement, originated in first instance by the fustian jackets, the blistered hands and the unshorn chins,” stated O’Connor.

The need for a much tighter organisation had seen the creation of the National Charter Association (NCA) in July 1840. It was at this point that the Chartist movement established itself as a working class political party – the first of its kind in history – with national rules, membership and constitution. The NCA reached a total of 50,000 members, organised in hundreds of branches.

“The agitation of Chartism,” ranted the Newcastle Journal, “brought to the surface of society a great deal of scum that usually putrefies in obscurity below.”

Chartism drew towards itself all the separate progressive movements within the working class. According to the historian Max Beer, “the expressions Chartist, Socialist, trade unionist and working man were synonymous terms.” Chartism became closely related to the mass struggles against the New Poor Law, the Ten-Hour Bill movement, as well as to the trade unions. In contrast, they were very hostile to the middle class leadership of the Anti-Corn Law League.

“Chartism is essentially social in nature, a class movement,” observed Engels. “The ‘Six Points’ which for the radical bourgeois are the beginning and end of the matter… are for the proletarian a mere means to further ends. ‘Political power our means, social happiness our end,’ is now the clearly formulated war-cry of the Chartists.”

“These six points, which are all limited to the reconstitution of the House of Commons, harmless as they seem, are sufficient to overthrow the whole English Constitution, Queen and Lords included”, stated Engels.

Unions and strikes

From April 1842, a new Chartist Convention met and launched another Petition, which gained over three million signatures. When laid out end to end, the Petition was said to be three miles long. The wording of the Petition was much more revolutionary than the earlier version, attacking the Royal family for its accumulated riches while the workers received starvation wages.

From April 1842, a new Chartist Convention met and launched another Petition, which gained over three million signatures. When laid out end to end, the Petition was said to be three miles long. The wording of the Petition was much more revolutionary than the earlier version, attacking the Royal family for its accumulated riches while the workers received starvation wages.

The Petition was attacked in Parliament with Thomas B. Macaulay saying “Such a confiscation of property and spoliation of the rich will produce misery, and misery will intensify the desire for spoliation…” This time it was rejected by 287 votes to 49.

The specific economic demands in the second Petition had served to draw the trade unions closer to Chartism. The idea of a general strike was once again revived. Meetings everywhere resolved “all labour should cease until the People’s Charter became the law of the land.”

A new storm of unrest broke out in the summer of 1842, which started among the Lancashire cotton spinners, spread to the Midlands and even to Wales and northwards into Scotland. It was called the “Plug Plot” strike, as strikers marched from factory to factory, removing the boiler plugs to shut down the steam engines. Chartism had attained its zenith.

The ironworkers and coal miners of Lancashire, the Potteries and Staffordshire took action. For over 50 miles around Manchester, the second largest city at the time after London, everything came to a complete standstill. It was the first modern general strike in history – and one where increasingly the demands of the Charter came to the fore.

On 7th August 1842, a huge workers’ Assembly decided not to resume work until the People’s Charter had been realised. A delegate meeting of Manchester trades put out the call: “we most solemnly pledge ourselves to persevere in our exertions until we achieve the complete emancipation of our brethren of the working classes from the thraldom of monopoly and class legislation by the legal establishment of the People’s Charter.”

A question of leadership

The struggle for the Charter had now fallen to the trade unions but the political leadership was completely taken by surprise. When the time came, they were found lacking. Even its left wing, in the person of Julian Harney, opposed turning the 1842 general strike into an uprising. However, they had no alternative but to support the strike, which was becoming increasingly militant and insurrectionary.

The Chartist leadership proved unable to direct the spontaneous movement of the working class into conscious revolutionary channels. Without direction, the strike inevitably weakened. The government increased its repression – arresting practically the entire Chartist leadership. In all, 1,500 arrests took place and 200 were later transported to Australia and Tasmania. The ruling class regarded the situation in the gravest possible terms. Sir James Graham, the Home Secretary, remarked: “We had the painful and lamentable experience of 1842 – a year of the greatest distress, and now that it is passed, I may say, of the utmost danger … We had in this metropolis, at midnight, Chartist meetings assembled in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Immense masses of people, greatly discontented and acting in a spirit dangerous to the public peace… For some time troops were continually called on, in different parts of the manufacturing districts, to maintain public tranquillity… For three months the anxiety which I and my colleagues experienced was greater than we ever felt before with reference to public affairs.”

The resulting defeat of the general strike – and with it the insurrection – dealt the Chartist movement a heavy blow. According to Engels, “The thing had begun without the working men having any distinct end in view… On this point the whole insurrection was wrecked. If it had been from the beginning an intentional, determined workingmen’s insurrection, it would surely have carried its point.”

An attempt was made to revive the Chartist cause with a fresh Convention in 1845 but the movement had effectively run out of steam. A new recruit, Ernest Jones, became O’Connor’s right-hand man and attempted to keep the organisation going but other causes, such as the Ten Hours Committees, sapped the movement’s strength and direction. It would require events in Europe to provide Chartism with the energy for one final stand.

1848: the year of revolution

The last great struggle of Chartism took place in 1848, a year of revolutionary movements across Europe, from which it took tremendous inspiration.

Indeed, it can be said that 1848 was the most revolutionary year of the nineteenth century. In London, mass crowds assembled in the open air at Clerkenwell Green and in Trafalgar Square to hear the Chartist leaders speak. Feeling revolutionary change in the air, Julian Harney wrote: “Every proletarian who does not see and feel that he belongs to an enslaved and degraded class is a fool.” Ernest Jones, Chartist leader, orator and writer, talked of “Class Against Class.”

Mass Chartist meetings were being organised and a Chartist Convention was called in April. They collected nearly two million signatures for another petition, although an additional number of names proved bogus.

Some 150,000 or so turned out for a demonstration in London. However the capital itself had been turned into an armed encampment. Parliament again rejected the Petition with 222 against and only 17 in favour. Mass arrests quickly followed, including that of Ernest Jones. From that moment, the great Chartist movement entered into a terminal decline from which it never recovered.

Chartism has nevertheless left us with a tremendous legacy that serves to educate and inspire all those who wish to change the world. We must adhere to Trotsky’s advice and study this historic movement.