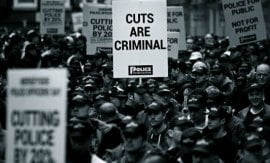

In this period of crisis, cuts and austerity, police officers are beginning to find that the shoe is on the other foot when it comes to being a victim of this government. The Police Federation, which is the representative body of police officers in the UK (although it is not a union), has organised two demonstrations in the recent period. The first was in 2008 and saw 20,000 officers march through London, while the second, in May 2012, attracted 30,000 officers protesting against cuts to pay and pensions, and changes to working conditions.

In the present period, this raises the question of the relationship between the police and the rest of the labour movement. On the one hand, police officers are fighting the same cuts that are being imposed on teachers, council employees, and other working people. All of these have a common cause – the crisis of capitalism – so surely we can fight against them together?

On the other hand, police have consistently been used to physically repress demonstrations and spy on left-wing organisations and activists. At the end of June 2013 it was revealed that the National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU), led by the Metropolitan Police, holds the details of 9000 “domestic extremists” on a secret database kept up-to-date by undercover officers, informants and communication intercepts. According to the Guardian, the unit monitors political activists from far-right fascists, to animal rights campaigners, to anti-capitalist demonstrators.

Given that extreme right-wing organisations and small pressure groups are unable to amass widespread support, it seems inevitable that the majority of those monitored by the NDEU are left-wing activists and trade unionists. One 88-year-old anti-capitalist protestor discovered that his presence at 55 demonstrations had been recorded by the NDEU, along with details about the slogans on his placards and the length of his facial hair

In addition, the policing of the student demonstrations in 2010 was extraordinarily heavy-handed, with the result that sixth-form student Alfie Meadows suffered a life-threatening brain injury at the hands of the police. Former undercover police officer Peter Francis has recently revealed that the Met launched a dirt-digging campaign against the family of Stephen Lawrence in an attempt to cover up the force’s own institutional racism.

So what should be the attitude of Marxists towards the demonstrations of the Police Federation, which have raised demands against police job losses and pay cuts and for the right to unionise and strike?

A Marxist view of the police

Clearly, we can have no illusions in the police in terms of their role within the capitalist state. Even after the 20,000-strong demonstration by the Police Federation in 2008, officers barely hesitated before kettling and beating student protestors in 2010. Police forces around the country seem incapable of shaking off corruption and malpractice scandals, with the new allegations surrounding the Stephen Lawrence case being the latest in a long line of similarly shocking revelations.

However, we should be careful not to equate the institution of the police with individual officers. While the institution represents one of the “bodies of armed men and women”, referred to by Lenin, that defend the ruling class and which must be overthrown by the revolutionary movement, the officers themselves should not automatically be tarred with the same counter-revolutionary brush. Behind the uniforms police officers are individuals and, like all individuals, their consciousness is shaped by their own experience of personal, local and world events.

The consciousness of officers is inevitably influenced by the fact that the duty of a police officer is essentially to coerce his fellow citizens to obey the law. Due to the nature and content of law in a capitalist society, it is the working class that is most often the subject of this coercion. In many cases this may attract people with a pre-existing class prejudice to a job in the police. Even if such prejudice is not already there, the day-to-day experience of coercing ordinary working class people to act in a particular way cannot help but impact on the consciousness of officers.

It is on this basis that some left-activists feel that police officers can never be anything but enemies of the working class. The position of the police is, in this respect, different from the army. In the early stages of the uprising in Libya in 2011 we witnessed thousands of soldiers deserting the regime and joining the ranks of the demonstrators. In one case the crew of a military jet preferred to crash the plane than carry out their orders to bomb the protestors. Similar scenes of military/protestor solidarity have been seen in Egypt, both in 2011 and 2013, and in other revolutionary movements including the October Revolution of 1917 that saw barrack after barrack coming out in support of the Bolsheviks.

Whereas police officers sign up for a job they know will involve coercion of working class people in their own countries, this is not the case for recruits to the army. Many of these recruits will be working class people themselves who see their role in the military as protecting their fellow citizens against external threats. If a government calls upon the military to intervene in domestic events, these soldiers are less likely than the police to side with the ruling class against their own people.

However, our analysis cannot end there, as there are other factors to be taken into account. The day-to-day work of policing creates a tendency towards reactionary conservatism amongst the police, but wider events are taking place at the present time that can create the opposite tendency in the consciousness of officers.

Police cuts

The number of police officers in the UK has fallen for four years in a row with 14,000 police jobs having been axed since 2010. Already the 20% budget cuts to police across the country have amounted to £2.4 billion and the government is now demanding a further 4.9% funding cut. This has resulted in recruitment freezes and pay cuts of 20% for new recruits. The result of this is described by one Special Constable interviewed by Socialist Appeal:

“There are fewer police officers on the ground which means resources are stretched and the force isn’t able to work as well as it could do with more police officers. I am personally peeved about the fact that there was a recruitment freeze, starting salaries were cut and now the force is taking on more officers at a lower rate because they can afford to. I feel very hard done by.”

As well as a 5-year increase in the retirement age from 55 to 60 and proposals to make it easier to sack serving officers, the latest burden on training police officers is the Certificate of Policing Knowledge (CPK). The CPK is a £900 course that must be taken by all potential new recruits to the police but which does not guarantee a job at the end of it. This Special Constable interviewed by Socialist Appeal explains:

“External applications are going to open soon for anyone with one of these certificates. For me, somebody who has given up the prospect of a full time job so that I can dedicate enough time to volunteering to allow me to join up soon, this is incredibly frustrating. I could have got a full time job, saved some money, done the course in the evening and stood just as good a chance of getting recruited. I also think it is elitist, because only people with £900 in the bank will be able to afford to become police officers. I find it slightly disgusting because I personally believe that this is a way in which the police have managed to find ways to cut the training budget; by making potential new recruits pay for a large chunk of it themselves.”

It is increasingly the case that a job in the police is another avenue that is being closed off for most young people in Britain. In this respect, those young people who aspire to join the police, for whatever reason, are finding themselves in the same position as millions of other young people around the world – just another number in the statistics, making up this generation of the best-educated jobseekers in history.

Effect on consciousness

These are the conditions in which current and future police officers are living and working. Such factors must leave a mark on the consciousness of these officers. It is no coincidence that the Police Federation recently balloted its members on the question of whether it should lobby the government for the right to take strike action, a right that police officers do not currently have. This is a response to the attacks on the police by the government.

The 1918 and 1919 police strikes in Britain are evidence of the militancy of the police when their pay and working conditions are attacked. One London policeman on strike in 1918 explained why he was on strike:

“We policemen see young van-boys and slips of girls earning very much more money than we get, and – well, it makes us feel sore”.

During the war, while the wages of the policemen were decreasing, their duties were increased. The action by police officers against the government was a direct result of the poverty and deteriorating labour conditions faced by the police. As one writer puts it:

“The traditional conservatism of the police was overcome as a result of their social and economic decline into the lowest sections of the working class.”

Just as the successful Bolshevik revolution in Russia had inspired the police in Britain, so the police actions were inspiring unrest in other sections of the British working class, with the National Union of Railwaymen formally urging workers to support the police struggle against the government and fears amongst the ruling class of a naval mutiny.

Eventually, the police were bought off with a 60% pay increase that satisfied all but the most militant officers, who were subsequently removed from the force. However, this action stands as testament to the Marxist argument that at certain stages the intensity of the class struggle can affect even the “armed bodies of men and women” of the bourgeois state.

Speaking to Socialist Appeal about police/government relations, a Special Constable had this to say:

“I would say animosity between the police and the government is quite widespread, in the sense that police officers feel we are being targeted by the government when it comes to spending cuts and changes to operational procedures. We are only being targeted in the sense that every public sector is facing difficulties, but this does create animosity between the police and the government who are seen as responsible for the personal difficulties police officers face in their financial situations or work life.”

The now infamous ‘Plebgate’ affair highlights this fracture between the ruling class and its armed body in a dramatic way. The fact that police officers were willing to fabricate evidence of a class-based insult made by a senior Tory minister to police officers, and then garner national media attention resulting in the minister’s resignation, shines a spotlight on the extent of the division. On this point our Special Constable notes:

“I don’t think that many police officers would be willing to go to the lengths that those officers involved in the Plebgate scandal did. They were an isolated case, but did of course highlight the friction that exists between the police force and the government.”

As previously mentioned, the Police Federation recently balloted its members over the question of a police strike. The result was that 81% of officers were in favour of lobbying the government for the right for officers to go on strike. However, because only 34% of the Federation’s 130,000 members cast a vote and its constitution states that the turnout must be over 50% for the action to be carried out, no further action has been taken. However, John Tully, chairman of the Police Federation for the Metropolitan Police, said that the results showed a full mandate to campaign for full industrial rights and his members were very angry that this campaign was not being taken forward by the Federation.

When asked, our Special Constable did not think that there would ever be circumstances in which it was justifiable for the police to go on strike, however she also said:

“I think the police should have the right to unionise to defend their employment rights. It is a scary time for everyone, especially new recruits joining up on lower starting salaries and with big changes being brought in, so I think the right to unionise could be important in helping us to stand our ground.”

It seems hard to deny that the current conditions of life and work for police officers are creating a tendency that runs counter to the seemingly innate conservatism of the police in Britain. The rumblings of discontent are already making themselves heard in the rank and file of the police and as the crisis continues and conditions worsen, those rumblings are only going to get louder.

Why is this happening?

As has been explained previously in Socialist Appeal, the cuts taking place across the world at the moment are the result of a global crisis of capitalism. But why are the police, the defenders of the ruling class, also experiencing cuts? Even Margaret Thatcher, the champion of the neo-liberal ‘small state’, avoided cutting police budgets because she knew she would need to rely on them as the class struggle intensified. Why have the current government not adopted the same attitude?

The first reason is that this is the deepest crisis that capitalism has ever known, and as a result the government cannot afford not to cut the police. This knocks down the argument made by those who believe the cuts to be ideological. If the Tories really were just cutting the things they hate, why on earth would they cut the police, an institution that can be relied upon to staunchly defend their class interests? The reality is that they have no choice under capitalism.

Secondly, the government may be surveying those so-called ‘leaders’ of the labour movement and estimating that they are more than capable of playing the part of the police in holding back the class struggle. The enormous chasm between the leaders of the movement and the rank and file workers means that ordinary people are continually frustrated in their attempts to fight the government over austerity. In fact, it may not be too far from the truth to say that many rank and file police officers are probably to the left of the Labour Party leadership at this stage!

Thirdly, the increasing privatisation of services such as electronic tagging and prisoner transfers may be an attempt by the government to give themselves greater ‘consumer choice’ when it comes to defending their class interest. However, as the recent scandal involving the fraudulent operations of G4S in relation to their government contract for electronic tagging have demonstrated, privatisation of these sorts of operations has its downsides for the Tories as well.

Against police corruption, brutality, racism and spying! For full industrial rights!

As Marxists, we cannot dismiss all police officers as incapable of siding with the labour movement in its fight against austerity. We can accept that the job of the police is inherently conservative, but that individual officers can be affected by the wider social and economic context of the real world. We should argue in favour of the right of police officers to unionise and go on strike. Through such organisation, rank and file police can be brought into the labour movement and closer to the working class, thus reducing the ability of the capitalist state to be used by the ruling class against the working class. And we should argue in favour of officers being allowed to unionise and take strike action without fear of being spied upon or having their details recorded on a secret database.

For many police officers, the idea of racism, corruption or police brutality is abhorrent, but as an institution the police seem interminably entangled in a scandal involving one or all of these things. Senior officers should be democratically accountable to the rest of the police force, and all police officers should be democratically accountable to the public. Working class communities should be able to oversee, judge, and democratically control the police locally, through the election of oversight committees from the labour movement, with elected representatives from the trade unions and local councils.

However, for all that you can democratise the police as an institution, you cannot chance the fundamental nature of the police as a force in society. The function of the police force cannot be fundamentally changed without changing society itself. The main function of the police force is law enforcement, so if we’re going to change the way the police behave a big part of that will be changing the nature of the laws that they enforce. As long as our legislative bodies defend capitalism, the laws that they pass will attack the working class. Only on the basis of the socialist transformation of society will you have laws that genuinely reflect the interests of working people.

Once the working class is in control of society – including the law and the creation of a new democratic state – the nature of any policing force in society will radically and qualitatively change. Following the socialist transformation of society, any policing force – if such a force was even necessary – would not be to protect the private property and interests of the capitalist class, but to protect the interests of ordinary working people, who for the first time would have democratic control over the running of society. Over time, the need for any state apparatus would “wither away” and disappear, the more so as class society in general disappears.

The labour movement should welcome the rising class consciousness and campaigns for industrial rights among the rank and file of the police, who can be brought closer to the side of the working class. We should work to nurture this sentiment against the reactionary nature of the role of the police in a capitalist society. Above all, bringing rank and file police into the labour movement undermines the ability of the capitalist state to repress the working class, and thus is a important pursuit in the class struggle.