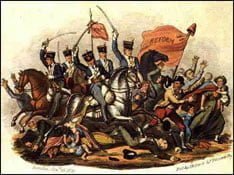

In the period of intense and bitter struggles described in Part 1, the massacre at Peterloo in August 1819 was just the most extreme example. Arthur Thistlewood was able to gather around him a mixed collection of other individuals equally impatient to bring matters to a head and have it out with the country’s political leaders. They believed that violent direct action was the answer.

Arguing that this would save the pointless slaughter of innocent people it was agreed that they would assassinate each and every member of the Cabinet, then parade through the streets with the heads of the most hated ministers.

Arguing that this would save the pointless slaughter of innocent people it was agreed that they would assassinate each and every member of the Cabinet, then parade through the streets with the heads of the most hated ministers.

The ordinary people of London would be overjoyed to witness the fate of their enemies and would flock to support them as they seized important public buildings such as the Houses of Parliament and the Bank of England. They would also capture the Mansion House and use it as the base for their Committee of Public Safety or Provisional Government. The Prince Regent would have fled, taking many of the soldiers from the London garrisons with him. Power would be theirs.

Getting carried away with their own rhetoric, they believed that they could call upon the support of 40,000 armed London working men, particularly among building workers, dockers, the Spitalfields silk-weavers and the navvies building what became the Regents Canal. The figure was almost certainly an exaggeration but even with half that number they might well have been a match for the limited forces of law and order in the capital.

The conspirators learned that on 23 February 1820, the Cabinet was due to meet at the home of Lord Harrowby, 39 Grosvenor Square. This was precisely the opportunity they had been waiting for. They decided to gather a collection of arms and to make their base in a garret in Cato Street, not far away. However, one or more spies had infiltrated the ranks of the conspirators and the proposed attack on the Cabinet was almost an open secret. A force of Bow Street Runners supported by Coldstream Guards surrounded the Cato Street premises, broke in and arrested several of the conspirators. Thistlewood and some others escaped only to be captured soon afterwards.

The man suspected of being the government spy, Edwards, had been at Cato Street and then disappeared. It is thought that the government spirited him overseas and away from the possibility of having to answer embarrassing questions. While popular opinion was not in favour of terrorist activity it found the practice of the government in using spies, provocative agents and stool pigeons to penetrate radical movements, totally repugnant.

Trial

In 1820 a biography of Edwards was published. It was extremely hostile and in the authors words: "Edwards was not merely an informer, who appeared to accede to the plots of others for the purpose of revealing and defeating them: he was a diabolical wretch who created the treason he disclosed, who went about – a fiend in human form – inflaming distressed and desperate wretches into crimes, in order that he might betray them and make a profit of their blood".

Being charged with treason, Thistlewood and his associates were taken to the Tower of London and placed in solitary confinement. The government used the subsequent trial to justify and reinforce its policy of oppression and the outcome was virtually a foregone conclusion.

The cause that Thistlewood was prepared to give his life up for was a justified one. If it is accepted that political change was needed, the issue was how to provide leadership for the movement that could actually bring that about. The fact is that isolated, idealistic individuals, no matter how committed, were not enough, and without mass support the Cato Street Conspiracy was nothing more than a terrorist adventure.

At his trial he justified his role. He invoked an example from Roman history when he said: "Brutus and Cassius were lauded to the very skies for slaying Caesar; indeed, when any man, or set of men, place themselves above the laws of the country, there is no other means of bringing them to justice than through the arm of a private individual.

With the execution of the Cato Street conspirators, the small extremist wing of the British radical movement effectively withered away, although the debate about the use of violence as a means of securing political change has continued to rear its head from time to time. The movement for political reform continued and grew and the years between 1830 and the early

1850s saw greater popular involvement in action for political reform and social justice than during any other period in British history.

The reforms that were won in the nineteenth century were the result not of the actions of brave but mistaken individuals like Thistlewood and his companions. They were brought about at first by the collective pressure of progressive middle-class elements and sections of the working class. Later a major contribution was made by the self-help organisations that working people established to fight for their own specific interests. These, especially the trade unions, were forged in struggle. They were not always successful, but those who took part gained a sense of their shared identity as ‘working class’. This collective strength made them actors in history, changing the world rather than simply finding themselves the victims of forces over which they had no control.

The nineteenth century saw the emergence of Marxism, an analysis and critique of capitalism and a revolutionary programme for workers everywhere to embrace in their struggles for social, economic and political justice. Marx made it clear that this was a class struggle involving collective mass action for change rather than violent action by individuals. Though it occurred some years before Marx’s writings appeared, this is also an important lesson of the Cato Street Conspiracy.