From the FIFA World Cup to the Olympic Games: under capitalism, today’s mega-sporting events have become vehicles for the profits of giant multinationals. Ray Physick analyses the situation of sport under capitalism and looks back at history at the alternatives provided by the international labour movement.

With increasing regularity elite international sporting events are beamed into the homes of billions of people by powerful television companies: from the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup, to the UEFA Euros, the African Nations Cup, the Asian Games, and the Commonwealth Games.

What these mega-sporting events all have in common is that they are sponsored by multinational corporations such as MacDonald’s and Coca Cola, and sportswear big businesses such as Nike and Adidas. Sports sponsorship is crucial for such companies as it greatly helps their market penetration. Another factor related to these festivals of sport is that participation is exclusive to elite athletes, who in turn help with the promotion of goods produced by the major sponsors of the events. Such events, therefore, have under capitalism become mere vehicles for giant corporations to advertise their commodities and make profits.

Elite sportsmen and women who ply their trade under the banner of international capitalism have not, however, always dominated international sporting festivals.

The profits of sport

Firstly, however, it is worth showing the extent to which the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup have become sporting festivals that are a vehicle for the reinforcement of capitalist, neo-liberal, market values. The London Olympics of 2012 cost the British taxpayer nearly £11bn, raised largely from the exchequer and from disguised taxation via the National Lottery.

In passing, it is also worth noting that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) demands that for the period of the Games the host city becomes a tax haven and that all the profits made from the Games accrue to the IOC without scrutiny of the host Government. FIFA demand a similar arrangement from their host nation, along with a promise for no protests to take place around stadiums.

Both the IOC and FIFA retain all TV revenues – for the London Games this amounted to $2.6bn – as well as all the sponsorship monies from the major multinational corporations.

Thus the British Government paid for all the stadiums and the infrastructure, placed this at the disposal of the IOC, who in turn raked in all the profits from the revenues listed above. Of course, contracts for building the Olympic Park were given to the private sector, another indication that, in the modern world of business, private enterprise is becoming increasingly parasitic in their dependecy upon government contracts rather than generating their own fields of investment.

Taxpayer’s money transformed what was previously a site of community engagement into a complex of various sports venues, the centre point of which was the Olympic Stadium. To ensure that the people of the world, who flocked to London for the Games, could buy consumer goods produced by multinational companies, an upmarket shopping mall was built adjacent to the Stratford interchange. Even the artistic centrepiece of the Olympic Park, the ArchelorMittal Orbit, designed by Anish Kapoor, and which cost £23m to build, was sponsored by Mittal, the multinational steel conglomerate. This is another demonstration that cultural practice is now a just field of profit making for multinational corporations.

High costs; expensive infrastructre: the “legacy” of sports events

Likewise the FIFA World Cup, starting in Brazil this week, reinforces the point that sporting festivals are an expanding field of profits for multinational companies. According to Forbes the costs for renovating seven stadiums and building five new ones have risen from $1bn to $3.5bn. These costs exclude infrastructure improvements, many of which, to the anger of millions of people, have failed to materialise.

Forbes noted that: ‘What’s driven up costs so high is mostly due to off-the-cuff arrangements between private companies and local politicians.’ In other words there is an air of corruption surrounding the whole event. The financial web site Bloomberg.com estimates final costs, including infrastructure improvements, will reach $14.5bn. The twelve stadiums will host 64 matches at an average cost of $125m per match. As The Guardian commented: ‘Only generals at war and Swiss sports officials contemplate such obscene spending.’

The infrastructure spending was supposed to be a lasting legacy of the 2014 World Cup and the forthcoming 2016 Olympic Games, both held in Brazil. However, the promised essential services have failed to materialise, transport costs have risen, in a desperate attempt the plug the financial short fall.

Brazil 2014: protests and anger

The response has been the magnificent movement of millions of Brazilians. These emerged last summer during the Confederations Cup and have continued unabated since. Alongside these protests there have been strikes by building workers working on the stadiums in protest over poor health and safety conditions. To date at least nine workers have been killed at the World Cup sites.

This does not mean that football is not popular in Brazil, but that support for the World Cup has decreased dramatically. The Guardian reported:

Public support fell from 80% when the cup was “awarded” to Brazil in 2007 to under 50% now. At the last count, 55% of Brazilians think the cup will harm their economy rather than benefit it.

The same newspaper is developing a blog about the protests that surround the forthcoming tournament. One comment makes it clear just how deep-rooted the feelings are in Brazil:

Even if I’m not protesting, I’m Brazilian and we want schools and hospitals, not a stadium that will probably fall to the ground in the first march. Don’t get me wrong, I love football, but I prefer my money to be spent on important things. It is good for the protests to be happening, ’cause the world needs to know what Brazil is like for real. Most people are poor and our government doesn’t care about us. Sad? Yes, it is. We Brazilians are sad and tired of so many injustices. Our streets are not painted in green and yellow because we know now that this World Cup was an excuse to make money.

Clearly, the movement against the spiralling costs has deep roots; almost certainly there will be attempts at further protest during the tournament. The authorities will, no doubt, attempt to neutralise these, but given the unstable nature of the police force in Brazil they may well find this difficult.

The needs of capital

The protests in Brazil are not so much against the FIFA World Cup per se, but are a response to neo-liberal economic policies of the Workers’ Party led by Rousseff and her predecessor Lula. The World Cup is in effect a symbol of how capitalism and the profit motive have penetrated sport and society.

In this instance the needs of capital override the rights of ordinary people. To date over 170,000 people have driven from their homes in Rio de Janeiro alone, a figure that falls short of 1.5 million evictions for the Beijing Olympics, but evictions in Brazil are still rising fast.

In an attempt to appease the anger of the masses living in the favelas the Workers’ Party Government appointed celebrity ambassadors, Pele and Ronaldo among them, to promote the benefits of Brazil hosting the FIFA World Cup. However, the tactic soon backfired with the protesters calling such celebrities ‘enemies of the people.’ Meanwhile, another famous footballer turned politician, Romario, has hurled abuse at FIFA and the IOC while asking the question how can Brazil pay for ‘first-world stadiums when we cannot afford first-world hospitals and schools?’

The Worker Sports Movement in the inter-war years

Several questions emerge from the above: do festivals of sport always have to reflect capitalist values of elitism and the profit motive? Does mass participation in sport have to be at the behest of multinational companies?

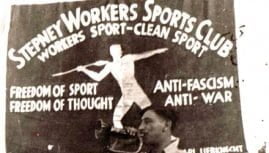

As referenced above festivals of sport were not always the preserve of elite athletes plying their trade under powerful governing bodies such as the IOC and FIFA, who in effect perpetuate the ethos of capitalism but in a sporting context. In the inter-war years there was a strong worker sports movement that culminated in three winter and three summer Worker Olympiads in 1925, 1931 and 1937 held under the Socialist Worker Sports International (SWSI) a body led by the Second International. The first two Olympiads were significantly larger than any of the bourgeois Olympics held between 1920 and 1936.

In addition to the Worker Olympiads, there were also one winter and two summer Spartakiads, all sponsored by the fledgling Soviet Union. The Spartakiads were held under the auspices of the Red Sport International (RSI), which was established in 1921 during the Third Comintern Congress in opposition to the SWSI. However, athletes from the RSI did participate in the third Worker Olympiad held in Antwerp in 1937 – a reflection of the Popular Front policy that had been adopted by the Stalin following the defeat of the workers’ movement in Germany.

Between the wars sport was an integral part of the Labour Movement internationally. The key country was Germany where over 1.3 million workers were members of sports clubs affiliated to the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Internationally over four million workers were members of the SWSI; thus sport in between the wars was an the important cultural expression of the working-class.

The first Workers’ Olympiad, held in 1925 in Frankfurt-am-Main, was attended by over 150,000 workers. In contrast to the bourgeois IOC Olympics of 1920 and 1924, which banned German and Austrian athletes, the Workers’ Olympiad expressed its international solidarity by including worker athletes from these countries. Moreover, the Games were held under the theme of international solidarity with the slogan of ‘NO MORE WAR’ being the central message.

The second Workers’ Olympiad was held in Vienna in 1931. 100,000 worker athletes actually took part in events while over 250,000 people from 26 countries attended the Games, the overwhelming majority being from the international labour movement. By contrast only 1,408 athletes participated in the Los Angeles IOC Olympics of 1932. The third and final Workers’ Olympiad was held in Antwerp in 1937 following the cancelled Barcelona People’s Olympiad due to be held in 1936. The Antwerp Games were much smaller than previous Games but they still attracted over 20,000 athletes, many of them from the Soviet Union.

Olimpíada Popular – Barcelona 1936

Perhaps the most significant Workers’ Olympiad was the one scheduled for Barcelona in July 1936. In 1931 both Barcelona and Berlin had bid to host the 1936 IOC Olympic Games, with Berlin winning the vote by 43 votes to 16.

The Montjuïc stadium, which was built to host the Universal Exhibition in 1929, was to be the main site for the Games. The revamped stadium hosted the 1992 IOC Olympics.

When Hitler came to power in 1933 the idea of a boycott of the Berlin Games gathered pace, an idea that manifested itself in Barcelona in February 1936 following the election of the Popular Front Government. By March the decision to hold a Olimpíada Popular, or a People’s Olympics, had been taken; the Popular Front Government transferred the 400,000 pesetas promised to the Spanish Olympic team for the Berlin Olympics to support Olimpíada Popular. The French and Catalan governments donated further grants of 600,000 pesetas and 100,000 pesetas respectively.

As the momentum in support of the Barcelona Games gathered pace it became clear that they would be larger than the IOC Games scheduled for Berlin. At least 10,000 athletes from 22 countries registered their interest in attending the Barcelona Games; by contrast only 4,000 took part in the Berlin ‘Nazi’ Olympics. It is also estimated that over 20,000 visitors were in the city to see the Games. Most of the athletes attending Barcelona had links with, or were sponsored by, the labour movement.

The Olimpíada Popular was scheduled to take place between 19-26 July but the Games had to cancelled due to the fascist rising led by Franco, which began on the 18 July. It is reported that many athletes meeting at their pre-arranged stations sang ‘The Internationale’, demonstrating that those taking part new the significance of what was taking place in Spain. In fact it is estimated that several hundred of the athletes stayed to fight for the revolution that unfolded in Catalonia following the fascist rising.

Sport, leisure and culture under capitalism

In contrast to the IOC bourgeois Olympics, the Workers’ Olympiads were based on international worker solidarity. The worker sport movement still continues today, but does not have the same power as the inter-war one.

Capitalist society sees sport as a key market for consumer goods: it also sees sport as a means for diverting people away from key social, political and economic issues. However, sport is an important part of social life and a socialist programme would include public, democratic control of all sports facilities.

Under a socialist system of production, workers would have a genuine platform for culture and sport, as opposed to under capitalism, where culture, leisure, and sport are the privelage of a small elite. Most importantly, workers would – with a plan of production – have the leisure time and the access to facilities necessary to participate in sport and culture.

The worker sports movement of the inter-war years is a microcosm of the cultural creativity that is latent within the international labour movement. For this to be fully realised the overthrow of capitalism is essential as this will provide the basis of a society based on the needs and desires of people rather than profit.