“I could not help being charmed, like so many other people have been, by Mussolini’s gentle and simple bearing… if I had been an Italian I am sure that I should have been whole-heartedly with you from the start to finish in your triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism.” (Winston Churchill, 1927)

“Satire is too good for fascists. What they require is bricks and baseball bats.” (Woody Allen, 1979)

As Britain and the rest of the world finds itself mired in the worst economic crisis since 1929, comparisons between the period we are now facing and the tumultuous events of the 1930s are often made. Some on the left, frightened by the actions of certain right-wing groupings, foolishly raise the prospect of a return to fascism. This is to completely misread the situation. While the EDL and BNP are certainly a danger on a local level, there is no basis for mass fascist movements as in the past. The ruling class burned their fingers with the fascists and will not want to repeat the experience. The social basis of fascism has also been completely undermined in comparison with the inter-war period.

These tiny groups are not the same as Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) of 1936. As their crushing in the last election and their subsequent collapse into bitter infighting demonstrates, there is no immediate prospect of the BNP attaining any sort of political power, either locally or nationally. The EDL, however, does represent a certain threat with their marauding football hooliganism and racist filth. They must be opposed. The experience of fighting the BUF in the 1930s demonstrates that such thuggery can only be defeated by a determined and united labour movement.

Slump

Fascism emerged for the first time in Britain in the shadow of the 1929-1933 world slump. This was the worst crisis in the history of capitalism with three million people unemployed and the Labour Party participating in a national government carrying out vicious attacks on working people. At the same time Mussolini had cemented his fascist rule over Italy and Hitler took power in 1933 . In this context, the BUF was formed by Mosley in 1932 and grew to some fifty thousand members at its height.

The BUF was aided in its growth by the funds and support of prominent British capitalists and aristocrats and the backing of papers such as the Daily Mail and Evening News.

The BUF had close links with the Conservative party and a number of Tory MPs openly supported Mosley.

With the experience of the 1926 General Strike still fresh in their minds, the British ruling class were terrified that the revolutionary movements sweeping Europe would spread to this country. In Spain the working class were engaged in a revolutionary struggle to the death against the fascists and in France a mass strike movement had created a pre-revolutionary situation that threatened to bring down the government. At the same time the British ruling class looked jealously to the crushed and bloodied people of Italy and Germany, completely cowed into submission by the domination of their fascist governments. They saw in fascism a stick with which they could beat the working class and forestall the prospect of revolutionary struggle. As Churchill once said of Mussolini:

“Italy has shown that there is a way of fighting the subversive forces which can rally the masses of the people, properly led, to value and wish to defend the honour and stability of civilised society. She has provided the necessary antidote to the Russian poison. Hereafter no great nation will be unprovided with an ultimate means of protection against the cancerous growth of Bolshevism” (Winston Churchill, speaking in Rome in January 1927)

It is a great irony that the most intelligent representatives of the bourgeoisie often share the same analysis as the Marxists. In this respect Churchill is absolutely correct in characterising fascism as the “ultimate means of protection” against proletarian revolution. In the final analysis then fascism is nothing more than:

“That special form of capitalist domination which the bourgeoisie finally resorts to when the continued existence of capitalism is incompatible with the existence of organised labour.” (Felix Morrow, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Spain)

Mosley

The particular circumstances of Britain meant that the ruling class was able to emerge from the slump without the need to cede direct power to the fascists as in Italy, Spain and Germany. Nevertheless they recognised in the BUF a useful tool that could be used to cow and intimidate the working class in times of crisis. This is why the BUF were able to operate under the protection of the state and received support and finance from large sections of the ruling class.

On the back of this support the BUF grew steadily, holding meetings and marches across Britain. They took cues directly from their European counterparts, with military fatigues, a swastika like insignia and a pseudo para-military group of violent thugs in uniform. At a mass rally in Olympia in June 1934 peaceful anti-fascists infiltrated the crowd to heckle Mosley. The fascist thugs responded by violently attacking them, men and women alike, while the police not only stood by but even joined in the attack against the anti-fascist protesters!

With its large Jewish population, East London became the main target of BUF activity. They launched a campaign of terror, smashing up and firebombing Jewish shops and physically attacking workers and immigrants. The Conservative, Liberal and Labour party leaders alike deplored these attacks but offered no solution, saying it was the responsibility of the police alone to deal with those who broke the law. Meanwhile the police did nothing to stop the fascists, instead they sent hundreds of officers to protect their meetings from the growing working class opposition.

At the same time there was growing working class opposition to the threat of fascism. The British workers had seen what the fascists had done to their German brothers and sisters and they weren’t prepared to let the same happen to them. Every fascist demonstration was met by an even greater counter-demonstration of workers and anti-fascists. All across the country the working class rallied against the fascists. They were prevented from holding meetings in Glasgow and in Bermondsey. The situation was building towards a decisive show down between the fascists and the working class.

The BUF then announced that on 4th October they intended to march through the East End of London to a massive rally in Victoria Park. This march was intended as a show of force and a provocation to the area’s large Jewish population. Desperate to avoid the inevitable violent confrontation that such a march would produce, five East London Mayors went to see the Home Secretary, Sir John Simon, to beg him to ban the march. He refused. The ‘Jewish People’s Council against Fascism and anti-Semitism’ launched a petition to ban the march which received over a hundred thousand signatures in a few days, yet still the Home Secretary refused.

This has direct parallels to the recent planned EDL march in Tower Hamlets where the local Labour party and others campaigned for the march to be banned. In this instance the Home Secretary willingly complied, not only banning the EDL march but all other marches across five London boroughs for a period of thirty days. In campaigning for the government to “ban the fascists” the workers must therefore bear in mind the following: history has taught us that the enforcement of laws by a capitalist state almost always acts to the disadvantage of the working class. Any laws introduced against the fascists will inevitably also be used against the workers. The working class can rely only on its own forces, not those of the capitalist state, to defeat fascism.

‘They Shall Not Pass”

In the absence of a ban the workers immediately began to organise resistance to the march. Despite the Labour leaders urging members to stay home and “leave it to the police” thousands came out in support of the anti-fascists.

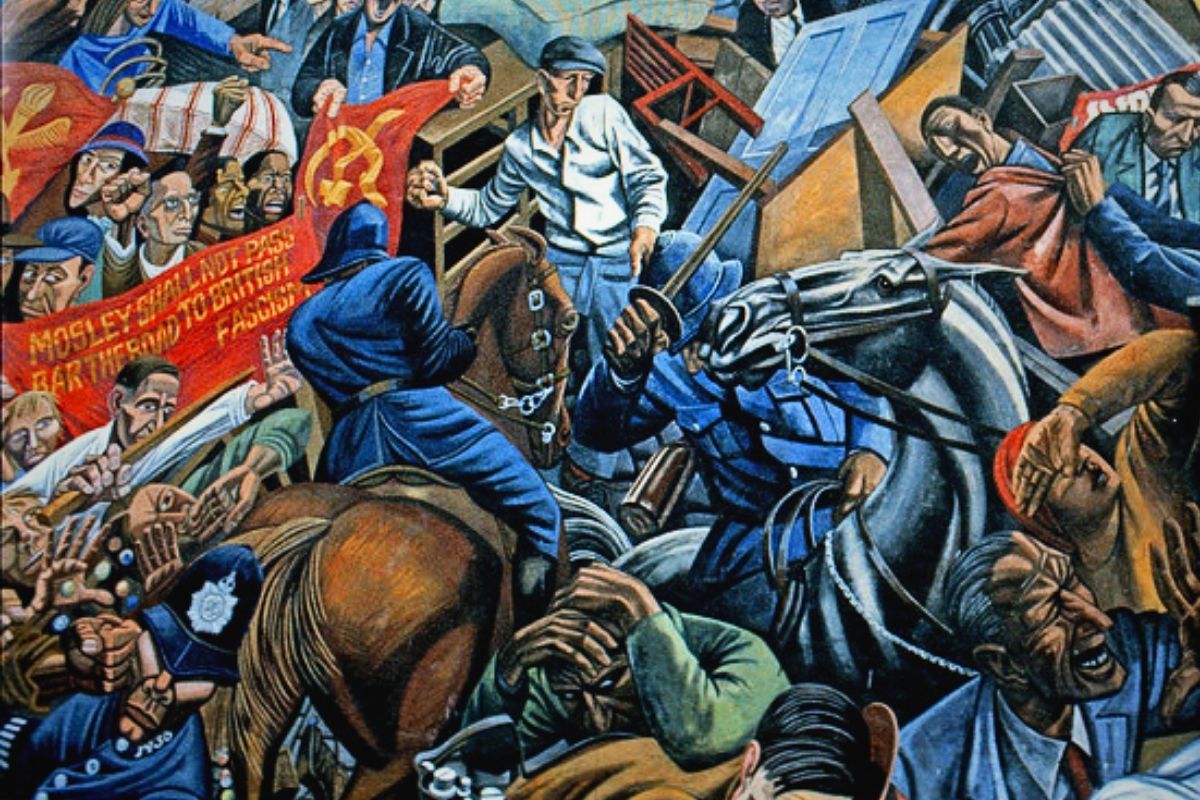

Reflecting the international character of the struggle against fascism and in solidarity with the Spanish workers fighting with their lives to prevent the fascists from taking Madrid, the slogan “They shall not pass” was adopted. It was agreed that a counter demonstration should be held at Gardener’s Corner to block their path.

On the morning of 4th October, three hundred thousand people had gathered to block the path of the fascists. Among them were the Labour Party, CPGB, Independent Labour Party, Young Communist League members and Trotskyists. The whole of the British working class was represented! Here was a true united front intent on crushing the fascist menace. The state had other ideas however. Over ten thousand police, including four thousand officers mounted on horseback, were brought in to clear the counter-demonstration and ensure the fascists could march. The seven thousand fascists were surrounded by a police escort for their protection. In order that the march could commence the police attempted to clear the counter-demonstration.

“At the junction of Commercial Road and Leman Street a tram had been left standing by its anti-fascist driver. Before long this was joined by others. Powerless before such an effective road-block, the police turned their attention elsewhere. Time and again they charged the crowd; the windows of neighbouring shops went in as people were pushed through them. But the police could make no impression on this immense human barricade” (Phil Piratin, Our Flag Stays Red)

Unable to clear the demonstration, the police attempted to move it down Cable Street. The workers, however, had anticipated this and were ready. As the police began to move down, street-barricades were erected from a lorry and bits of old furniture.

The police charged the barricades and were:

‘…met with milk bottles, stones and marbles. Some of the housewives began to drop milk bottles from the roof tops. A number of police surrendered. This had never happened before, so the lads didn’t know what to do, but they took away their batons, and one took a helmet for his son as a souvenir.” (Phil Piratin, ibid)

All the time, the fascists cowered behind police lines as the police carried out the battle on their behalf. As Mosley arrived, a brick flew through his car window. Faced with such hardened resistance, he was forced to call off the march. Shamed at not having even attempted to confront the workers, the fascists lined up in military formation and marched in the other direction!

Defeat

This was a comprehensive defeat for Mosley and the BUF. As Ted Grant, himself a participant in the Battle of Cable Street, wrote:

“The defeat at Cable Street in 1936 dealt a severe blow to Mosley. Afraid of the organised might of the working class so militantly demonstrated, the East End fascist movement declined. The spectacle of the workers in action gave the fascists reason to pause. It induced widespread despondency and demoralisation in their ranks; their victory over the fascists imbued the working class with confidence. This united action of the workers at Cable Street demonstrated anew the lesson: only vigorous counter-action hinders the growth of the menace of fascism.” (Ted Grant, The Menance of Fascism).

It is therefore important that we remember the lessons of Cable Street. It is only through the power of the working class that these thugs can be decisively driven from our streets, be it the fascists of old or the hooligans of the EDL today. At the end of the day, however, only the struggle for socialism can eliminate the scourge of reaction.