The world of international finance has been shaken by the

default in Dubai.

Shares have taken a tumble all over the world. Commentators have suggested that

this could be the cause of the recession moving into a double dip, of a further

downturn in the world economy.

What has happened? Dubai World has asked for a 6 months

What has happened? Dubai World has asked for a 6 months

moratorium on its debts. That means it can’t keep up the payments. It’s in big

trouble. The bankers reckon the company owes $60bn all around the world. Dubai

World is not just a private company. It’s an arm of the government, run by the

ruling sheikh. The vast sums it borrowed carried an implicit state guarantee.

As we now know, this guarantee was worthless. Dubai World issued bonds, which

are supposed to be much safer than shares. Its paper was seen as safe as Dubai government bonds.

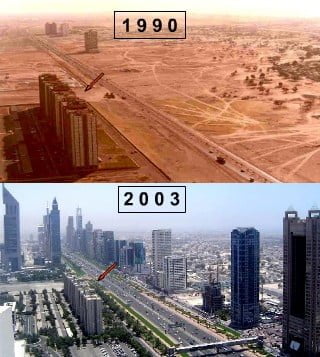

Dubai

is a comic opera country. One of the United Arab Emirates, it has a

population of 1.2 million, most of whom are from abroad. Dubai started life as a sleepy fishing port.

With less oil revenue than most of the other Emirates, Dubai World launched an

immense construction boom aimed at turning the town and surrounding desert into

a place for the super-rich to hang out. They built the tallest tower in the

world. As plush apartments went up all over Dubai, so did the rents and Dubai World

became very happy and very, very rich. But the party is over. They have

recently had to abandon a half-built project to build islands in the shape of a

map of the world in the Gulf, all holding luxury accommodation.

Why should we worry about the fate of a company in the Gulf?

Because capitalism is a global system and it knits all our fates together. When

it was doing well, Dubai World bought that iconic firm of British imperialism,

P & O. They bought the Adelphi building in the Strand, Grand Buildings

in Trafalgar Square

and a share in the London Eye. They bought the QE2. They own 51% of Southampton container terminal and are currently

developing the London Gateway Port.

But still Dubai World kept borrowing. The Bank for

International Settlements estimates that the United Arab Emirates as a whole owe

$123bn to the rest of the world. It looks like we can kiss goodbye to a lot of

this money. Guess what? $50bn of the cash is due to UK banks. HSBC is owed $17bn, Standard

Chartered $7.7bn, Barclays $3.5bn, RBS $2.3bn and Lloyds TSB $1.5bn. So it goes

on.

White expatriates in Dubai

have been living the life of Reilly till recently, with ‘all you can eat’

brunches in five star hotels on Friday (This is actually code for ‘all the

champagne you can guzzle’.) and Ferraris as standard issue. That the building

boom was a bubble about to burst was plain for all to see, but everybody

enjoyed the party to the full as long as it lasted.

Life for the workers who actually threw up the skyscrapers

was a little different. Lured from impoverished neighbouring Arab countries or

the Indian subcontinent by tales of wages they could keep their families on

with ease, their passports were confiscated upon arrival and they became indentured

labourers, in effect slaves in Dubai.

But Dubai is part of the

world economy and, when recession came, it hit Dubai hard. They could no longer fill all the

luxury apartments they were building, rentals collapsed by 50% and they stopped

building flats. The construction boom came to a sharp halt a year ago and the

foreign building workers were packed off home. There are still 40,000 dwellings

in the process of being built over the next two years. They will not find

buyers, so the depression will not go away soon.

The trouble was Dubai

was really nothing more than a gigantic building site. The default of Dubai

World is really the national bankruptcy of Dubai. This is the second country after Iceland to be

forced into bankruptcy as a result of the crisis of capitalism. The results of

national bankruptcy were a catastrophe for the people of Iceland

Sovereign default is the latest thing capitalist

commentators have become seriously vexed about. You can bet on anything under

capitalism. You can buy a bit of paper called a Credit Default Swap (CDS) and

bet on the chances of a country defaulting. All countries are perceived as

becoming riskier as the government deficit balloons. For instance UK public debt

was 46% of GDP in 2006 and is assumed to reach 89.3% next year, nearly doubling

in consequence of the crisis. As a result $24bn is being bet against the

possibility of UK

government securities defaulting compared with just $12bn in 2006.

Why might a nation be unable to pay its bills? Because

government debt has swollen on account of the economic crisis. Crisis means

government receipts such as taxes fall, while the state has to pay out more in

benefits. In many cases the fiscal crisis of the state has been made worse by

the need to bail out the banks. The government then borrows from other

countries to cover the shortfall, and starts to slide down the slippery slope.

Now the latest twist in the tale means UK banks look likely to take yet another body

blow, this time from Dubai.

No doubt they will be lining up in the not-too distant future demanding that

the government bails them out one more time, increasing government debt still

further. The global interdependence imposed by capitalism may mean all

countries share increased prosperity in a boom, but in a recession it spreads

misery all over the world from the remotest, apparently accidental, incidents.

It’s possible the establishment may be able to organise a

rescue for Dubai.

It is expected that oil-rich brother Emirate Abu Dhabi may move to bail out the

prodigal Dubai,

after some grumbling. And the losses may ‘only’ be $60bn, compared with $600bn

in the case of Lehman Brothers last year. But the finances of Dubai World are

far from transparent. There could be some nasty surprises lurking in the

detail.

Events have already proved quite dramatic, shaking the

confidence of the financial establishment all over the world. This will not be

the last we hear of the dangers of national bankruptcy. As Gillian Tett asks in

the Financial Times (22.11.09) “Will sovereign debt be the new subprime?” She points out that banks are being exhorted

to hold government bonds as an asset on the grounds that they are safe. There

is bound to be pressure on governments to print money and, through inflation,

erode the value of the bonds. The Dubai World default shows that government

securities are not always safe and their promises cannot always be relied on.

The banks could be packing their vaults with more toxic waste.

How can a country try to get out of the peril of falling

helplessly into debt to other countries, triggering national default? One way

is by devaluing its currency, letting it fall against other national currencies

so that exports are cheaper and imports dearer. But countries in the Euro-zone

do not have this emergency exit. They can’t devalue because they share a common

currency. Interest rates and monetary policy are the same in all nations across

the region, set by the European Central Bank, so they can’t print money to get

out of trouble either.

"Creditors need to take part of the responsibility for their decision to lend to the companies…They think Dubai World is part of the government, which is not correct. Dubail World was established as an independent company; it is true that the government is the owner, but given that the company has various activities and is exposed to various types of risks, the decision, since its establishment, has been that the company is not guaranteed by the {Dubai} government." Addulrahman al-Saleh, director generalof Dubai’s department of finance (trying to keep a straight face) – quoted in the Guardian 1/12/09

Actually some countries in Euro-land are feeling the heat

more than others. The weaker economies in the South of Europe, often spoken of

disparagingly as the ‘Club Med,’ are really struggling with the effects of the

crisis. The Greek government is running a government deficit of 12.7% of GDP

(more than four times the permitted European maximum), which means the

government’s debt will hit 135% of national income. Greece has a deficit with

foreigners of 14.5% of GDP and foreign debts amounting to 150% of national

income.

At present the Greek government has to pay 178 basis points

(nearly 2%) more in interest than the Germans to speculators to hold on to

their10 year bonds. Clearly the speculators demand higher rates because they

fear the Greek government may default. As Lars Christian of Danske Bank

comments, “There is enormous denial…They can’t devalue; they can’t print

money.” George Papendreou, the incoming

prime minister, is in despair at how dire the finances are. “Our country is in

intensive care,” he warns. “This is the worst crisis since the restoration of

democracy” (in 1974). A Greek default would be much more serious than that of Dubai. It would throw the

whole of Europe into turmoil.

The crisis is putting immense pressure on all the countries

The crisis is putting immense pressure on all the countries

of the Euro-zone and upon the existence of the Euro itself. It stalks one

country after another, probing for weakness and laying the weakest low. The

example of Dubai

could have global consequences. It could in its turn knock over a lot more

dominos in the world economy. Capitalism is inherently unstable. As long as it

exists, it threatens all our livelihoods.