Britain faces an impending water crisis. 35 years of privatisation have burdened water utilities with unsustainable debts, fears of capital flight, dated infrastructure, sewage dumping, and threats from climate change.

This reveals the troubling consequences of a system prioritising private profit over public wellbeing.

Parasitic water monopolies

Since privatisation in 1991, water monopolies have prioritised shareholder payouts over investments that would benefit the public and secure the future water supply.

Britain’s 16 water monopolies have distributed £78 billion in dividends, while simultaneously accumulating over £64 billion in debt.

Privatised with zero debt, these companies have transformed into heavily indebted enterprises with insufficient funds for the infrastructure improvements necessary to meet future demand.

The ‘super-sewer’ Tideway project for example, aimed at improving London’s sewage capacity, is being paid for by Thames Water customers.

At the same time, the cash-strapped company has continued paying out large dividends to fund the project, and compensation for new boss Chris Weston is reportedly worth £2.3 million.

Adding to the scandal, Britain’s largest water utility is reportedly seeking investments from foreign state entities, including Abu Dhabi, Chinese sovereign wealth funds, and Canadian pension funds.

These state-backed organisations have deemed that as it stands, Thames Water is “uninvestable”. This means an outrageous 53 percent hike in bills by 2030, just to maintain operations.

Failing this, Thames Water bosses are balancing between the options of extortionate emergency loans from creditors, or a takeover bid by Castle Water.

Castle Water is owned by former Tory treasurer Graham Edwards – through a British Virgin Islands holding company. This sleazy politician is trying to profit even more from this crisis by funnelling funds to a tax haven!

Allowing foreign sovereign wealth funds, investors, and tax havens to profit from water utilities means placing our national resources at the mercy of international capital.

This is why Labour has ruled out renationalisation – Starmer and Reeves know they must make the UK attractive for foreign investment. They need to guarantee return on investment by allowing companies to raise water prices and circumvent environmental regulations.

This tension starkly exposes the reality: that without public ownership of the commanding heights of the economy, the state has limited power to protect public interests against corporate profiteering.

Infrastructure decay

Water infrastructure in Britain is ageing, with much of the sewer system over forty years old, exacerbating the risk of urban flooding and pollution from untreated sewage.

This September brought record-breaking rainfall, pushing already overstretched drainage systems to the brink.

According to recent projections, if trends continue, Britain could face water shortages as early as the 2030s. A lack of clean drinking water could become commonplace in Britain, as it is in parts of the Mediterranean.

On a broader scale, inadequate infrastructure and climate change have intensified the vulnerability of urban areas to flash floods, transport disruptions, and pollution.

In many cities, outdated systems fail to manage increased rainfall and urbanisation, further compounding flood risks and environmental degradation.

Nationalise and expropriate

The crisis in Britain’s water sector exemplifies how capitalism commodifies essential resources, turning public needs into profit-making opportunities, while sacrificing long-term security for the good of all.

While everyday citizens face skyrocketing costs and dwindling resources, the capitalist elite manoeuvres to tighten their grip on public utilities for profit.

We must expose their schemes, fight for a system that expropriates these parasites, and put water back into public ownership, accountable to workers and consumers.

Only then can we ensure that decent water is a necessity available and accessible to all, not a commodity to be exploited.

Youth services in crisis – a view from the front line

Nick Halsworth, Manchester RCP

I am a youth worker for a youth centre in Manchester, in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK.

We do vital work offering working-class young people a place to go, fun activities, informal extracurricular education and skills, creative arts and sports, and pastoral support.

Many kids I work with are let down by schools. They live in communities with few resources or opportunities, beset by unemployment, poverty, crime, and poor mental and physical health.

Decades of austerity and decline have created a bleak world for working-class young people. Youth services attempt to address this. But we are working against many obstacles.

Since 2010, youth services have been cut by 69 percent. More than 4,500 youth work jobs have been cut and 750 youth centres closed.

With no public funding, provision has been forced towards the private sector and philanthropy for funding.

The founder of one the UKs largest gambling firms put up the money to build our centre! Most of our costs are covered by corporate partnerships: hedge funds, insurance companies, real estate developers, etc.

We are always worried about bringing in enough money to stay open. How much goes towards paying fundraising managers, which could be directed towards more workers and better resources?

We are constantly understaffed. Youth workers make basically minimum wage, working anti-social hours. I’ve seen many passionate youth workers leave as a result.

The sector must be unionised, as part of a wider campaign to fight against austerity and the system that breeds it.

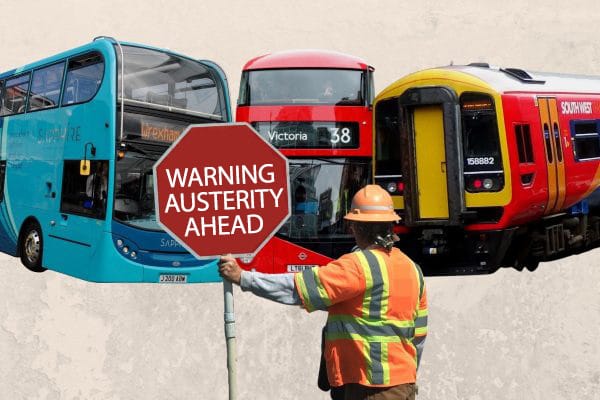

Bus fares hiked; workers and youth squeezed

Roo Humble, Cardiff RCP

In a pre-budget speech, Starmer revealed that his government would make another “tough decision”: ending the £2 single bus fare cap.

The cap was introduced by the Tories in the face of soaring living costs. There were hopes amongst voters that Labour would extend the cap. But these have been quickly quashed.

Other than in London and Manchester, the cap will be raised to £3 – a 50 percent increase.

Consequently, a student who relies on buses to get to school will see their annual travel costs rise from £760 a year to £1,140.

Busses are also the only option for many workers around the country. The end of the cap will see a larger chunk of their wages going on daily travel.

This will particularly affect people in rural areas who depend on public transport.

“It’s bloody shit. As a student I am devastated,” one young person told The Communist. “£2 per trip is already expensive, especially if you have to take multiple buses and then get home again. £3 is crazy!” exclaimed another.

As one worker in Cardiff explained, “buses are slower, less convenient, less reliable, and about the same price as using my car, but I still use the bus because it’s less stressful than driving in heavy traffic. However, the price rise may tip me over to using my car.”

He is also worried about the effect this policy will have on the climate crisis: “Air pollution kills around 40,000 people a year. We need efficient and accessible public transport to save the planet.”

Whilst the cost of the crisis falls on the working class – including bus drivers, who have taken strike action in many areas in recent years – the CEO of Stagecoach pockets a tidy £1.7 million per year.

The company was fully compensated for the cap, with public money ensuring high profits and happy shareholders.

Capped fares are not enough. Private bus companies must be expropriated. And these vital services must be put under workers’ control!