We publish here the second part of a Socialist Appeal document on the perspectives for the class struggle in Britain. In this second of three parts, we look at the special crisis of British capitalism, which is undergoing a century-long process of decline. The result is seemingly endless austerity and attacks for the working class, the youth, and the poor.

We publish here the second part of a Socialist Appeal document on the perspectives for the class struggle in Britain, which was discussed at the recent conference of Socialist Appeal activists and supporters. Although initially written in December last year (and therefore already overtaken in places by new events and developments), the document provides an analysis of the main processes affecting British politics and society, as well as outlining the fundamental contradictions facing the ruling class and leaders of the labour movement.

In this second of three parts, we look at the special crisis of British capitalism, which is undergoing a century-long process of decline. The result is seemingly endless austerity and attacks for the working class, the youth, and the poor. In turn, the cuts to pay, public services, and terms and conditions are creating a groundswell of anger against the Tory government, reflected in part on the industrial plane – but above all on the political plane in the shape of the Corbyn movement.

British economic decline

The optimistic propaganda of the government about the British economy is completely misplaced. While it is true that the UK grew faster than Europe, this was due to the fact that Europe has been in and out of recession for the last six years. But the reality is that the British economy is now slowing down, and is only being kept afloat by consumer spending. Without this, Britain would already be in a deep recession.

In July, manufacturing had its sharpest fall in four years. Building has come to a halt, private car sales have fallen, house sales are the lowest since June 2008, and investment has almost frozen. Infrastructure spending has fallen by 23% over 2015, as projects are scrapped or put on hold. According to the Office of Budgetary Responsibility, net public sector investment fell from £51.5bn in 2009 to £33.6bn in 2015-16. This is set to fall every year to 2020.

The services sector, which now makes up nearly 80 per cent of the UK economy, was responsible for all of the third-quarter growth in 2016, expanding 0.8 per cent. The three other sectors — industrial production, construction and agriculture — contracted. The strength of services continues the pattern since the slump of 2008, with output 12.1 per cent higher than its pre-crisis peak. In contrast, manufacturing is still 5.6 per cent smaller than at the start of 2008 and construction 1.3 per cent lower.

The foundation of any modern economy must be its industrial base. This has been severely eroded over the last 40 years of de-industrialisation. Britain, once the workshop of the world, has been reduced largely to a rentier economy, based on finance, banking and services. Decades of industrial decline has undermined the position of British capitalism, reducing it to in effect a second rate power. This is what we have called the special crisis of British capitalism. The responsibility for this collapse lies squarely on the shoulders of the ruling class, which has failed to modernise and re-equip British industry, especially in the face of increased competition. Brexit will reduce the UK’s status even further.

“These areas have been deindustrialising for a long time. The end of the old manufacturing sectors — and the disappearance of plentiful and reasonably well-paid jobs for low-skilled men — started in the 1970s, with British industry going through the most rapid change of all in the 1980s. But we should note that everywhere, it was not the amount produced by factories that fell — it didn’t — but that production could increasingly happen with fewer workers thanks to technological change”, explained the Financial Times (23rd November 2016).

This reveals the squeeze that has taken place: fewer workers producing the same output. Machinery is used to squeeze out more surplus value. This is an example of the increase in relative surplus value that Marx talked about. The pressure and stress on the nerves of workers has increased as the degree of exploitation increases.

Much of Britain’s manufacturing industry is now foreign owned. Just take the example of the steel and car industries. In the seventies, more than 200,000 people were employed by the state-owned British Steel Corporation, but after privatisation the number fell to 40,000 and is now below 30,000. One in six of the remaining jobs are deemed precarious. It was owned by a Dutch corporation but is now in the hands of Tata Steel, an Indian conglomerate. Back in the 1970s, the car industry was still mainly British-owned, but is no longer the case. Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) was bought by Tata from Ford.

Other car companies operating in the UK are Nissan and Honda, Japanese companies. China’s Geely have plans for a £250m new factory to manufacture black cabs. The UK is no longer engaged in cheap mass production but upmarket cars. The UK car industry is more of an “assembler” of cars than a manufacturer. Only about 40% of the parts that go into cars made in Britain are sourced here, though the figure is about 50% for JLR. But whilst car output and exports may be rising, this sucks in more imported components. Fourteen of the world’s largest 15 auto parts firms are based in Germany, Japan, the USA and France – all countries that still have a large domestically owned producer.

Professor Karel Williams, of Manchester Business School, argues the weakness of the domestic supply chain has been driven by the pattern of foreign ownership. Williams said:

“It’s not simply about the number of shiny cars off the line; it’s about the amount of British componentry under the bonnet. And the problem there is the cars in the 1970s were basically 100% British. And the percentage is now much lower.

“If you correct for the imported content, we will still only be producing something around two-thirds the value of output that we produced in the 1970s, and indeed probably significantly less than we produced in the late 1990s.”

The degree of foreign penetration of British industry is a reflection of the failure of the British capitalists to invest. They developed a short-sighted approach. Rather than invest and produce real wealth, they turned to property speculation, financial services and areas that gave quick returns. This is a reflection of the degeneration of British capitalism. This once workshop of the world has been transformed into a rentier economy and a key assembly platform for foreign multinationals. Finance capital has emerged as the dominant force, with its interests in the City, insurance and banking. This in turn, given its different interests, has served to undermine Britain’s industrial base.

In 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power, Britain produced 122million tons of coal from nearly 300 mines, with the vast majority underground mines and about 60 open-cast. Since then, the coal industry has been privatised and then closed down, for political reasons. However, Britain still depends on coal for up to 40% of its electricity generation. As a result, despite having 700 years of coal supplies underground, Britain is now dependent upon imported coal, shipped across the world, mainly from Russia, but also from the US, Colombia and Australia.

The fact that Britain has to import so much has meant that it has now built-up a massive £100bn balance of payments deficit, over 5% of GDP. Britain has a current account deficit of £24.6 billion with the European Union alone. The trade gap in the UK widened to £5.2 billion in September 2016, reaching the highest in three months. Exports fell 0.4 percent while imports jumped 2.5 percent, hitting a record high. Total exports decreased by £0.2 billion to £45.4 billion while total imports rose by £1.25 billion to £50.6 billion.

Considering only goods, the trade deficit was £12.7 billion, widening by £1.6 billion since August 2016. The goods deficit with EU countries has reached an all-time high of £8.7 billion. This is at a time when sterling fell by more than 10 per cent against the dollar and euro, supposedly making British exports cheaper and more competitive. Most likely, manufacturers simply jacked up their prices and pocketed the difference, as was the experience in the past.

British capitalism’s reliance on financial services and the City of London is not a source of strength but a source of weakness. It is no accident that Britain was hit the hardest in the slump of 2008, with a greater fall in GDP than in 1929-1931. This fragile basis of the economy has become even weaker. On top of this, Brexit is likely to inflict particular damage on banking and financial services companies, some of which are already looking at relocating their headquarters overseas. The accumulating weaknesses of this rentier economy mean that the next slump will again hit Britain particularly hard.

If Britain is forced out of the Single Market it will be an economic disaster for British capitalism. Almost 50% of UK exports go to Europe. Tariffs on British goods – as well as imports – will have massive costs and plunge the economy into difficulties. “The process of unravelling four decades of political and economic integration will be complex, costly and frequently bad tempered”, writes the Financial Times. “The Britain that emerges will be weaker economically and have a smaller foot print internationally.”

The Tory government is at present facing profound economic and financial difficulties. Philip Hammond, known as “spreadsheet Phil”, has talked about scaling back of austerity. But with the economy slowing down, the government will be forced by the economic situation to increase austerity, not decrease it. The Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast growth in 2017 of 1.4 per cent – down from 2.2 per cent expected in the March budget – as greater economic uncertainty slows business investment and higher inflation hits consumer demand.

By the end of the decade, public borrowing will be £30bn worse a year, according to the OBR, compared with the budget forecasts. They forecast that public sector debt will rise to 90.2 per cent of national income by 2017-18. Over the five year forecast period to 2021, the government will have to borrow over £120bn more than it had planned in the March budget.

This is in sharp contrast to figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility, which forecast in March that the public finances would improve from a £76bn deficit last year to a £10bn budget surplus by 2019-20. Instead, Hammond will face a deficit of £15bn in 2019-20 — a shortfall of £25bn compared with the OBR’s projection. That is why Hammond has abandoned the unrealistic aim of a budget surplus by 2020.

The economy’s reliance upon consumer spending will be its Achilles’ heel. The squeeze on incomes will have serious effects on growth, which will slow down even further. “The outlook for 2017 remains poor,” said James Knightley of ING. “Consumer spending is likely to come under downward pressure as inflation eats into household purchasing power.” This, in turn, will mean lower tax receipts and increased debt. With the economic difficulties facing Britain there is little room for manoeuvre. The government is still faced with delivering all the spending cuts planned for the next three years, which have already been decided.

But there are growing signs that public services are reaching breaking point after six years of cuts. Ominously, the riot in Bedford Prison, after guards lost control of one of the wings, shows the breakdown in the prison service. The number of prison officers was cut sharply between 2010 and 2015. This riot took place only three days after Liz Truss, justice secretary, outlined plans for 2,500 additional prison officers to be recruited to help address rising levels of violence in prisons.

The frustration among prison officers led to illegal strike action across the country, which shook the government. “Circumstances are against him”, states the Financial Times. “After six years of spending cuts, the strains on public services — from prisons to hospitals — are becoming apparent.” However, it goes on to warn: “Yet the UK is still some way from bringing current spending to a level consistent with likely tax revenues.” In other words, cuts will still have to continue in order to balance the books, but over a slightly longer period.

Hardship Britain

This is not an isolated case. There is anger and bitterness everywhere. The number of workers living in poverty has reached record levels according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Workers have faced more than a decade of declining real wages and on present trends will earn no more by 2021 than they did in 2008. Average earnings fell 9 per cent between 2008 and 2013 as wages failed to keep pace with inflation. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies this is the worst period for workers’ pay in at least 70 years. “One cannot stress enough how dreadful that is — more than a decade without real earnings growth,” said Paul Johnson, head of the think tank. Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England described the last 10 years as a “lost decade”, where real wages have not risen for the first time since the 1860s, adding ominously that this was the time when Karl Marx was scribbling in the British Library about revolution.

Real wages in the UK were hit badly after the crisis and the forecasts suggest real wages will be hit hard again. With the turmoil over Brexit and the fall in the pound, inflation will be pushed up. As a result, the IFS forecasts that real wage growth will stall next year and even by 2021 average earnings will be below their 2008 level.

Food price inflation will in particular squeeze those at the bottom. Helen Barnard, head of analysis at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, said that “The poorest fifth of people in the UK spend £1 in every £6 of their income on food, much more than middle-income earners, so a price rise will have a bigger impact on the household budgets of less wealthy families.”

These cuts in real wages, combined with looming benefit cuts, are predicted to squeeze living standards even further. This will add to the feelings of anger and resentment that exist. Even in the summer and autumn of 2015, NATCEN social attitudes research revealed that three-quarters of respondents said that the “class divide” was very or fairly wide. The research concluded that people who see society as divided between a large disadvantaged group and a small privileged elite “feel more working class regardless of their actual class position.” 45% now want taxes and public spending to rise, while 10% want taxes and spending cut. In other words, only a tiny percentage is in favour of austerity. 40% believe there should be higher spending on welfare benefits, the highest figure since 2003. Significantly, today, the same proportion – 60% – identified themselves as working class as in 1983, a year before the year-long miners’ strike.

Stress at work has been rising consistently. Today, 33% of workers said they were “always” or “often” stressed, up from 19% in 2005. On the other hand, there has been growing concern over the ability of health and social care services to meet rising demand for these services. As a result there has been a sharp increase in the use of hospital beds as people are unable to leave hospital because no suitable care is available. The number of hospital beds taken up by patients suffering from malnutrition has almost trebled in a decade, according to official figures.

The situation is becoming unbearable. The 31 per cent reduction in council grants had led to a £4.6bn cut in social care spending. Some 400,000 fewer people were receiving care funded by local authorities in 2014/15 than in 2009/10, even though the number of older people has risen significantly. “There is a time bomb about to go off,” said Steve Brady, Labour leader of Hull council, while councillor Izzi Seccombe, chairman of the Local Government Association’s Community Wellbeing Board, said services across the country were “at breaking point”.

The government will be increasingly backed into a corner, especially as the economy deteriorates as a result of Brexit and a new world downturn. As soon as people realise what is going on, and that could be quite soon, the government’s popularity will plummet like a stone.

The Lib Dems, which acted in the past as a safety net for disillusioned Tory voters, have been shattered after their five-year collaboration in coalition with the Tories. From over 50 MPs they were reduced to just a handful. It is possible that, thanks to the on-going uncertainty over Brexit, the Lib Dems could pick up in the polls. This was what happened in the Richmond Park by-election in December. But this phenomenon is unlikely to last very long because the crisis of capitalism is affecting all the major parties, starting with the Lib Dems, squeezed by the political polarisation and the consequent collapse of the centre ground.

UKIP, a mixture of rabid reactionaries whipped into frenzy by anti-immigration rhetoric and more “respectable” Thatcherites, has benefitted from the collapse of the centre ground. Feeding on the general discontent with all the main political parties, they took advantage of the EU issue to challenge the Tories from the right. Together with pressure from the right-wing Tory Little Englanders, this forced Cameron to accept the fatal referendum on Europe. He managed to stem the rise of UKIP but at an enormous cost to British capitalism. But with Brexit negotiations now underway, UKIP can continue to put pressure on the Tories and gain support by highlighting every deviation of May’s and proclaiming themselves to be the only true champions of Brexit.

The new leader Nuttall aims to build support by challenging Labour in the Northern working class “rust belts”, based upon anti-immigration demands and chauvinism. Given the despair in these areas, and the rotten legacy of the Labour Party, an “anti-establishment” UKIP could pose a certain threat. The betrayals of reformism are responsible for this. A majority of Labour’s rotten boroughs are in these working class areas, which have been badly affected by the crisis of capitalism. Only the emergence of a left-wing Labour Party, with a clear fighting programme, could cut across this danger.

The trade unions

The discontent of the working class in Britain has not so far been manifested in a mass wave of strikes. In fact, the trade union struggles have been on a low level. Whereas in France the discontent of the workers expressed itself in an outburst of strikes and demonstrations, in Britain the strike movement is at a low ebb, the movement being held back by the trade union leaders.

The British trade union leaders see their role simply as mediators. They have acclimatised themselves to the capitalist crisis by repeatedly making concessions to the bosses. As “realists”, workers are asked by the union leaders to make sacrifices to keep their jobs, but their jobs are never safe. Workers are faced with a continual squeeze. Weakness invites aggression and the bosses take full advantage of the weakness displayed by the trade union tops.

Despite the cuts in real wages and the attacks on jobs and services, the trade leaders have led not a single national industrial struggle for years. Where they have been pressed to call some action it is always half-hearted and is quickly ended. Most recently Community and others have caved in to everything Tata Steel has demanded at Port Talbot, including big cuts to pensions, without a fight. It is the trade union leaders who are responsible for a whole series of retreats. They hide behind the Tory anti-trade union laws to justify their passivity.

The six-million strong TUC is a faint shadow of its former self. It does nothing and leads nothing. It has been reduced to issuing press releases. The TUC Congress passes motions for action, but nothing comes of it. It even passed a motion to consider the feasibility of organising a general strike, but this was kicked into the long grass. Rather than conduct any struggle, it lays down before the Tory government, which introduces even tighter anti-trade union legislation.

Trotsky once said that there is no greater conservative force in society than the trade union leaders. This remains true today as it was then. The union leaders are desperately striving to avoid a confrontation. They are quick to cling to whatever crumbs the Tory government has to offer. The suggestion by Theresa May that workers should be put on corporate boards was hailed as a tremendous advance. They saw this proposal as a means of furthering their class collaboration policies, fostering a brotherly “unity” between worker and boss, but the employers have no need of such an arrangement at the present time and the idea was soon abandoned under pressure from the bosses.

With the weakness of the union leaders, the employers feel they have the whip hand. The TUC leaders complain and moan, but do nothing. If they call rallies under pressure, they are merely used as a chance to blow off steam.

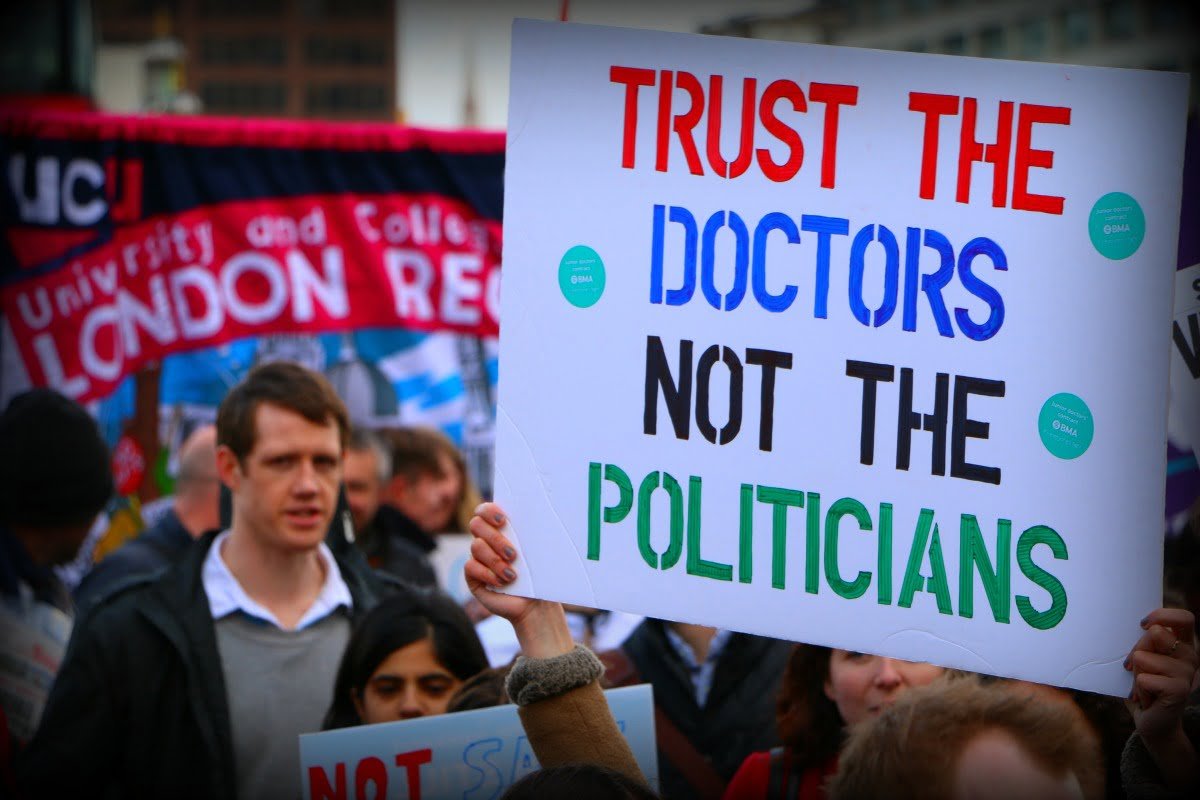

The struggle of the junior doctors – which had been considered a privileged layer in the past – and which started so promisingly, but has ended without a deal. The government is now attempting to impose its new contracts, which will increase resentment. But without a clear strategy from the BMA leadership to win the dispute, and planned strikes suspended, the dispute seems to be petering out.

Other disputes, such as on Southern Trains, London Underground, prison officers, London ambulance drivers, post office staff and the teaching assistants have continued. Led by the RMT, workers on the privatised railways have seen the profits that are being made and are prepared to take action on a regular basis to defend their position. Guards, in particular, have been at the forefront in demanding action. ASLEF drivers on Southern are also taking action.

As stated, the union leaders act as a colossal brake on the movement. Instead of uniting the different strikes, they isolate them. They are fearful of any movement that could get out of hand. In late 2011, they were forced to lead a coordinated strike over pensions involving nearly 30 unions. But as soon as they were granted a few crumbs by the government, they rapidly brought the action to an end. This strike showed the potential strength of the unions. It is clear that the most successful strategy today for the unions is not partial strikes in different sectors, but a nationally coordinated action of several unions, acting as one. This would be a serious challenge to the bosses and the government and give confidence to workers.

Attempts to block industrial action by the employers’ use of the courts should be met with further industrial action. Weakness invites aggression. Instead, the union leaders have run away from confronting the anti-union Laws. In fact, when challenged, they put their faith in the bourgeois courts to act “fairly”. Such behaviour demonstrates their whole outlook. But their backtracking will eventually provoke a reaction within the union rank and file.

Nevertheless, the trade unions remain a key element in the equation. Despite the decline in membership, millions of workers are organised in the unions. There is a layer of younger workers who are discontented with the conduct of the leadership. The new generation of shop stewards will not be so easy to control as the old, tired elements who will be retiring in the next period. The potential was already shown by the marvellous militancy of the young doctors.

With new cuts being imposed and the health service at breaking point, new clashes are inevitable. With prices rising, workers will be pushed into action in order to try and keep up. The trade union leaders will continue to act as a dead weight, resisting calls for a serious coordinated struggle against the Tories. However, they will be under ever-increasing pressure from below and implacable resistance from the government and employers.

Pressure on the union leaders will also come from outside the ranks of the organised working class. Casualised layers working for Uber and Deliveroo have taken legal action and launched wildcat strikes in defence of their pay and conditions. This has proved that these casualised workers can be organised to take industrial action, if only the trade union leaders make the effort to do so. This has already forced a response from Unite, which is now focusing more energy on workers caught in bogus self-employment. The Deliveroo strike in particular also showed that militant strike action can win disputes, a fact that will not be lost on rank and file trade unionists pushing for bolder measures from their leaders.

At a certain point the trade unions will be forced, reluctantly, to engage in struggle. The union leaders will be under pressure from the rank and file to take action. They will pass from semi-opposition to open opposition to the Tory government. But even the stormiest strikes and demonstrations cannot solve anything fundamental. Sooner or later the demands of the workers will assume a political form. Already the process of radicalisation was shown by the big support for Jeremy Corbyn in the unions.

The main focus of the class struggle has been in the Labour Party. Trade union members have participated in this political struggle. The revolutionary process is not manifested in strike statistics alone. In Britain the movement in the direction of revolution is being reflected not on the industrial plane, but on the political plane, where it is causing a deep crisis in the main political parties with incalculable consequences for the future.