We are publishing here the first part of a document on the perspectives for the class struggle in Britain, which was discussed at the recent conference of Socialist Appeal supporters. Although already overtaken by events in places, the document explains the main processes affecting British society, as well as outlining the fundamental contradictions facing the ruling class and leaders of the labour movement.

Over the next few weeks we are publishing for our readers a Socialist Appeal document on the perspectives for the class struggle in Britain, which was discussed at the recent conference of Socialist Appeal activists and supporters last weekend. Although initially written in December last year (and therefore already overtaken in places by new events and developments), the document provides an analysis of the main processes affecting British politics and society, as well as outlining the fundamental contradictions facing the ruling class and leaders of the labour movement.

We begin, in part one (of three), by commenting on the international background of global economic crisis and political turbulence that lies behind the volatile events in Britain, and by looking at the impact of the Brexit vote and the unfolding turmoil and acrimony within the Tory Party. Despite the apparent strength and stability of Prime Minister May and her Tory government, it is clear that a period of intense storm and stress for the British Establishment and their political representatives.

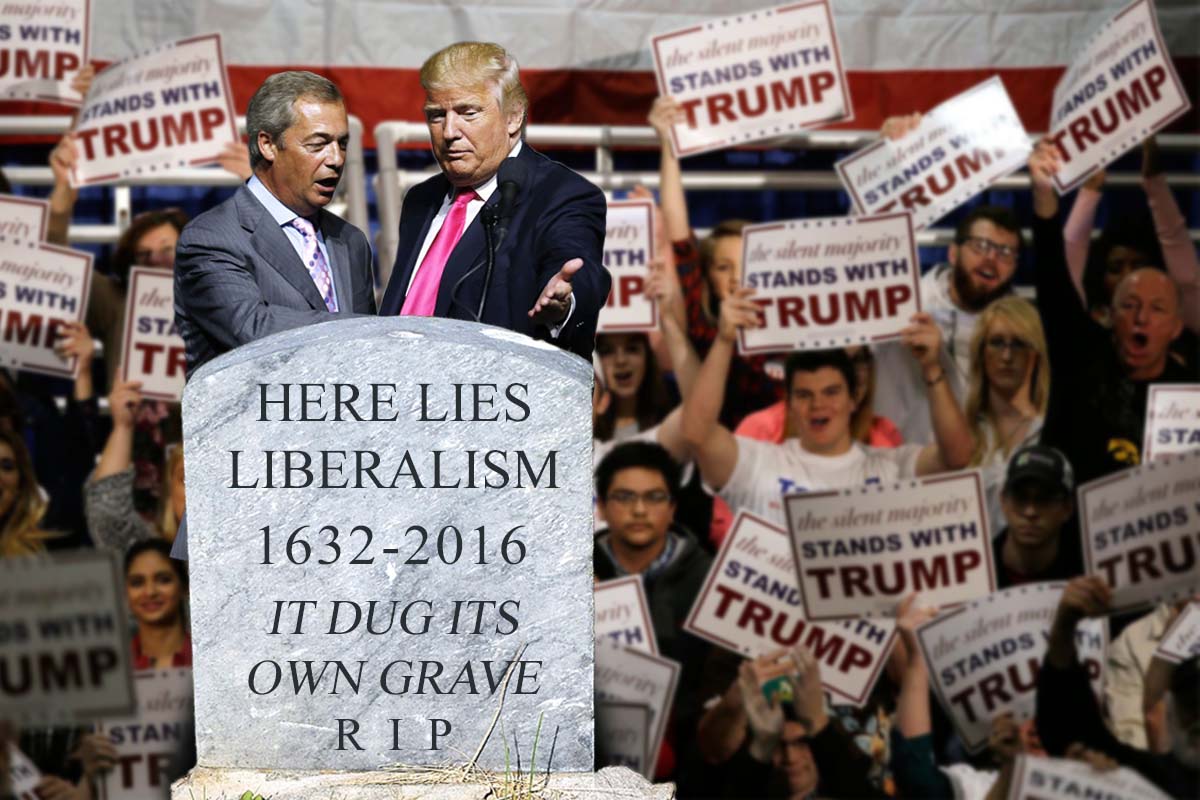

“The fall of the Berlin Wall, on November 9th 1989, was when history was said to have ended. The fight between communism and capitalism was over. After a titanic ideological struggle encompassing the decades after the Second World War, open markets and Western liberal democracy reigned supreme. In the early morning of November 9th 2016, when Donald Trump crossed the threshold of 270 electoral-college votes to become America’s president-elect, that illusion was shattered. History is back—with a vengeance.” (The Economist, 12th November, 2016)

The situation in Britain is developing much faster than even we dared to predict. Of course, it is impossible to predict exactly the tempo of events. The task of Marxists is to outline the general processes developing in society as a guide to action.

In January 2016, the Royal Bank of Scotland announced that the prospects for the coming year were “cataclysmic”. While there has been no new world slump or Great Depression, as of yet, political events can certainly be described as “cataclysmic”. First with Brexit and then with the election of Donald Trump, everything has been turned on its head. Some have described it as “the politics of insurrection”, a very apt description of what is unfolding.

As we have explained repeatedly, the deep crisis of capitalism has opened up an extremely turbulent period, the most turbulent in history. This is affecting society politically, socially, economically and in every other way. This extreme turmoil is now plain for everyone to see. This is an epoch of sharp and sudden changes, in itself a reminder that the capitalist system has reached its limits. “We are sort of reaching the limits”, stated Agustin Carstens, governor of the Bank of Mexico. “In many countries monetary policy activism has run its course.” One by one the pillars of a previous period of relative stability are being destroyed.

This “new normality”, also reveals itself as a crisis of reformism, opening up unprecedented possibilities for revolutionaries. Our task is to understand the present epoch and analyse the situation as it unfolds and then draw all the necessary conclusions.

The shock of Brexit was followed by the election of Donald Trump, whose “America First” policy threatens to end the 70-year-old US world order imposed after the Second World War. This political earthquake, which is shaking the capitalist world, epitomises this fundamental change taking place on a world scale.

“Donald Trump’s victory is no ordinary shock. For once the word seismic is merited”, explained the Financial Times. These events, which seemed impossible, are a reflection of the powerful underlying current of discontent and anger that has been building up within society.

The slump of 2008 was a turning point. Ironically, the bourgeois commentators following the 2008 slump were crowing that the Left was dead. These superficial “experts” were deceived by the slowness of the reaction of the masses, who were temporarily disoriented by the suddenness of the collapse. “Where is the worker backlash?” they asked. “Where is the rebellion?”

Human consciousness is very conservative and it requires time for the masses to absorb the meaning of a new situation. But sooner or later it catches up with a bang. This is an expression of the dialectical law of the transformation of quantity into quality. Now this delayed backlash has arrived with a vengeance.

This does not necessarily take the form of strikes, although there have been between 30 and 40 general strikes in Greece over the past few years. But there is a dramatic political radicalisation, reflected in a furious reaction against the status quo. There has been an accumulation of anger and rage against a system that produces obscene riches together with an accumulation of misery, suffering and the agony of toil.

This development, which was predicted by our tendency, was delayed for a long time, but history moves at its own pace. The contradictions take time to work themselves out. The capitalists in turn take measures to put off the crisis, but they eventually run out of the means to do this. Now the system has reached a blind alley.

As Marx explained, when a social system cannot develop the productive forces, it enters a into period of crises and revolution. This is precisely the character of the present epoch. The old order that was created in the post-war period is crumbling. And to use Marx’s expression, the mole of revolution has been busy burrowing away and it is now pushing its way through to the surface.

The system has not experienced a serious revival since the 2008 crisis. This is what makes it different to previous crises, including 1929-33. Instead, a period of “secular stagnation” has set in. World trade, the main springboard for the capitalist upswing for more than 25 years, has dramatically slowed down and now threatens to go into reverse. This is deeply disturbing for the bourgeoisie.

In the past, it was world trade, which expanded much more rapidly, that pulled along world production. This is no longer the case. “Globalisation”, which extended and deepened the world market for a whole period, now threatens to go into reverse. The adoption of “America First” policies in America threatens to provoke a wave of protectionism throughout the world.

We must remember that it was precisely protectionism, competitive devaluations and beggar-thy-neighbour policies that led to the Great Depression in the 1930s. Protectionism is basically an attempt to export unemployment. That is the real meaning of Trump’s slogan: “America first”. He intends to “make America great” at the expense of the rest of the world. But as each capitalist power attempts to unload the problems onto its neighbour, the outcome will be the outbreak of trade wars that can undermine the whole edifice of globalisation, creating an unstoppable downward spiral in the world economy.

This is viewed by the strategists of capital with growing alarm. Robert Kagan writes in the Financial Times: “None of this should sound far-fetched. This narrow, interest-based approach to foreign policy was dominant in the 1920s and 1930s. It is the preferred strategy of many American academics today. More importantly, it plays well with an American public that has come to believe the US has been taken to the cleaners. Mr Trump promises they will not be taken for suckers any more.

“How long can this new era last? Who knows? Americans after 1920 managed to avoid global responsibility for two decades. As the world collapsed around them, they told themselves it was not their problem. Americans will probably do the same today. And for a while they will be right. Because of their wealth, power and geography they will be the last to suffer the consequences of their own failures. Eventually they will discover, again, that there is no escape. The question is how much damage is done in the meantime and whether, unlike in the past, it will be too late to recover.” (Financial Times, 19th November 2016)

In the past, capitalism was able to move forward and develop by creating its own market. The capitalists reinvested the surplus value extracted from the unpaid labour of the working class, which developed the productive forces and allowed the system to advance. But sooner or later the market becomes saturated. Now there is massive overproduction on a world-scale, which they call “excess capacity”.

In such a situation there is no incentive to invest to create new capacity, since new investment will only make things worse. The capitalist system finds itself in a blind alley from which it cannot escape. “The real barrier of capitalist production is capital itself”, explained Marx. The crisis of capitalism is not created by external factors, as the bourgeois economists imply, but is born out of the internal contradictions of capitalism.

This however does not mean that capitalism will automatically collapse. It will endure until it is consciously overthrown by the working class. They will try everything to escape from the crisis. But the consequence will be the driving down of living standards, to squeeze more surplus value from the workers. The perspective is one of a long period of austerity. That is a finished recipe for class struggle everywhere.

Contradiction is piled upon contradiction. The economic witch-doctors have reduced interest rates to zero and even to negative levels, whilst Quantitative Easing (QE) – pouring money into the system – has also been tried and failed. Out of desperation the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are continuing to pour money into the economy through QE. But such measures simply create distortions in the economy and create further contradictions by feeding speculative bubbles. As a result, world indebtedness continues to rise inexorably, preparing the way for a new and even deeper collapse.

Political instability

Every attempt to restore the economic equilibrium serves to destroy the social and political equilibrium. The election of Trump in the United States was simply the latest in these shocks. It will not be the last.

“Start with the observation that America has voted not for a change of party so much as a change of regime”, explained the Economist. “Mr Trump was carried to office on a tide of popular rage. This is powered partly by the fact that ordinary Americans have not shared in their country’s prosperity…

“Anger has sown hatred in America. Feeling themselves victims of an unfair economic system, ordinary Americans blame the elites in Washington for being too spineless and too stupid to stand up to foreigners and big business; or, worse, they believe that the elites themselves are part of the conspiracy. They repudiate the media—including this newspaper—for being patronising, partisan and as out of touch and elitist as the politicians. Many working-class white voters feel threatened by economic and demographic decline. Some of them think racial minorities are bought off by the Democratic machine. Rural Americans detest the socially liberal values that urban compatriots foist upon them by supposedly manipulating the machinery in Washington. Republicans have behaved as if working with Democrats is treachery. Mr Trump harnessed this popular anger brilliantly.” (The Economist, 12th November 2016)

The bourgeois strategists fear that the inevitable disillusionment with Trump at a certain stage can lead to the emergence of even more extreme forces. “The danger with popular anger, though, is that disillusion with Mr Trump will only add to the discontent that put him there in the first place”, explained the Economist. “If so, his failure would pave the way for someone even more bent on breaking the system.”

The same processes exist everywhere. The backlash against the status quo (at root against capitalism) has fuelled the rise of anti-establishment parties to the right and to the left. In the USA, it was reflected in the rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. The Sanders movement is part of the same process and is more significant from our point of view.

Millions of Americans looked to this self-professed “Socialist” as he lambasted Wall Street and the bankruptcy of capitalism. “We need a political revolution against the billionaire class”, he said, as he spoke to millions of voters. It is quite incredible that in the land of the McCarthyism and extreme anti-Communist propaganda, 69% of those under 30 years-old said they would vote for a Socialist for the President of the United States.

In a Gallup poll, 49% said they would vote for a Socialist. “Both Mr Trump and Mr Sanders are running from the fringes of their parties”, explained Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times. “Both have said things that would be regarded as political suicide in a normal year. Mr Trump is probably the most openly racist candidate since George Wallace, the segregationist, in 1972. Mr Sanders calls himself a ‘democratic socialist’ – in a country that has always rejected socialism. Yet the fact that both men are happy to smash rhetorical taboos has strengthened their respective claims to be genuine outsiders. That seems to be what voters are looking for…

“What is already clear, however, is that America’s political class is only beginning to grasp the depth of the anti-establishment mood that is gripping the US. Almost eight years after the financial crisis, this mood seems to be growing in strength, not weakening. President Barack Obama’s announcement last week that the US unemployment rate is now below 5 per cent barely registered on the campaign trail…

“If America’s yearning for anti-establishment leaders from the political fringes continues, the implications will be profound — for the US and for the world. The system, dominated by the Democrats and Republicans, has always rejected the political extremes. That means that, behind the day-to-day dramas, the nation has benefited from a deep political stability, which has contributed greatly to its economic strength and global power. If America’s immunity to extremism is ending, the whole world will feel the consequences.”

And these consequences will be far-reaching. The same process of anger and rebellion against the establishment exists very much in Europe. The rise of SYRIZA in Greece (before the betrayal of Tsipras), the rise of Podemos in Spain, Brexit and the rise of Corbyn in Britain, the Independence Referendum in Scotland and the demise of the Scottish Labour Party, the rise of the Front National in France, the rise of the Alternative for Germany party, and a host of other anti-establishment parties and movements to the right as well as the left reflect this phenomenon.

The masses are seeking a way out of the crisis. This is manifested in a series of violent swings of public opinion to the left and also to the right. The whole situation is becoming polarised. These are the first symptoms of a revolutionary crisis, which will develop over the coming years.

There is the prospect of a world slump that will be deeper than the crisis of 2008. The danger of such a slump has been highlighted by fears of a slowdown in China, or a crisis in Europe, possibly prompted by a banking collapse in Italy which would reverberate through Europe and beyond. A new world slump will certainly exacerbate the crisis of the old parties, which will be faced by convulsions and splits.

The bourgeois strategists are very worried about the future. The French Presidential election in the spring of 2017 will be followed by the German elections, which could lead to unexpected outcomes.

Every area of the world is being sucked into this vortex. From Trump in the US to the upheavals in Brazil and Venezuela, from Brexit to the crisis in Europe and in the Middle East, from the rebellion of the youth in South Africa to the biggest single strike action in world history in India, involving between 150 and 180 million workers. No country can escape from this process. This applies particularly to Britain.

Impact on Britain

Britain was once held up as a very stable capitalist country. The Tory Party was the most successful bourgeois party in Europe. The British ruling class sneered at the instability on the European continent. But all that has now changed. The crisis has finally hit home hard. British society has been thrown into the melting pot and is now one of the most unstable countries in Europe.

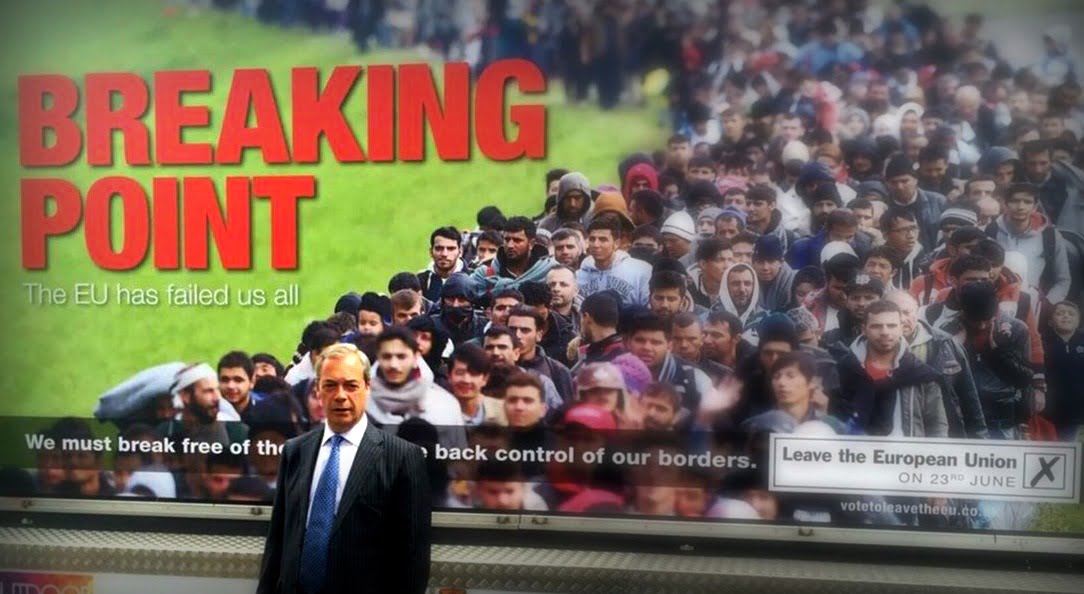

Suddenly Britain is facing the most serious political and constitutional crisis since the Second World War. The fact that Britain has had two constitutional referenda in two years is indicative of this instability. The victory of Brexit last June and the ending of almost half a century of close relations with Europe has created a shockwave which will reverberate far beyond these shores. It threatens the very future of the European Union, stoking the flames of anti-EU discontent throughout the continent.

It is true that the whole Leave campaign was permeated with racism and xenophobia, but the Brexit vote also reflected an anti-establishment mood and a reaction against the status quo and all the main Westminster parties. It was a rebellion by the dispossessed and forgotten people of those areas of Britain that were destroyed by Thatcher’s “counter-revolution”. The idea that such areas would be “stronger in Europe” sounded ironical to those on the scrapheap. By voting for Brexit they hoped somehow to “take back control” of their lives and communities that had been ravaged by capitalist crisis and deindustrialisation. Any racist and xenophobic sentiment amongst this section of the class, however, is overwhelmingly superficial, and could be cut across by a socialist programme, if one was offered by the labour leaders.

“Historians will see the largest revolt against political, business and financial elites as the nearest Britain has come in centuries to a revolution”, warned former prime minister Gordon Brown. “This is not just a British problem. In country after country, the gap between the promise of globalisation and people’s day-to-day experiences of insecurity, joblessness and stalled living standards is so stark that we are bound to see more ‘take back control’ protests.”

While the comment about “revolution” is exaggerated, Brown has a point. Brexit was driven by the same forces as with Trump in the United States, the Scottish Referendum and the victory of Corbyn. In different ways, these phenomena are part of the same process.

“The evidence so far suggests that the Brexit and Trump campaigns appealed to the same sort of voters”, explained the Economist, “those who feel they have been marginalised, or even victimised, by the march of globalisation. According to polling immediately after the Brexit vote, those who voted to Leave were trying, in Mr Trump’s words, to ‘take their country back’, or make it great again. Whereas nearly three-quarters of Remainers thought that life in Britain was better today than 30 years ago, 58% of Leavers said it was worse. Among Leavers, 80% thought that social liberalism had been a ‘force for ill’, 74% thought the same of feminism and 69% of globalisation. In other words, they were flatly rejecting the liberal worldview of an open, equal country that successive governments have cultivated over the past few decades. Ring any bells?”

The article concluded: “The open markets and classically liberal democracy that we defend, and which had seemed to be affirmed in 1989, have been rejected by the electorate first in Britain and now in America”.

“This as a vote that changed everything. Economic and foreign policies crafted over nearly half a century overturned in the course of a single night”, lamented the Financial Times. “A political establishment shattered by an insurgency against the elites. The nations of the UK divided; and England split between its metropolitan cities and post-industrial provinces. A vote against globalisation. A decision that weakens Europe and the West. Political earthquake is an underestimate.” (24/6/16) The paper then went on to describe it as a “roar of discontent from the nation’s working class heartlands.” (30/6/16).

The Brexit result came as a profound shock to the ruling class. Although there were divisions, their interests had been tied to the European single market for the last 43 years. The majority was in favour of Remain, but they had completely miscalculated, just as they had miscalculated over Scotland’s independence referendum. David Cameron, the Tory Prime Minister, only narrowly avoided the destruction of the United Kingdom.

Both these “upsets” were down to the political short-sightedness of Cameron, who had put his personal short-term interests, as well as those of the Tory Party, above the “national interest” (namely the interests of the bankers and capitalists) and the dangers posed to British capitalism. This time, Cameron gambled and lost spectacularly. This forced his immediate resignation and threw the establishment into deep political crisis.

Cameron’s political short-sightedness is not accidental, but an individual manifestation of the crisis of British capitalism. The declining standing of the bourgeois runs apace with the narrowing horizons of the Conservative Party. In place of the old grandees have come the upstart Thatcherites, their outlook determined by their base in finance capital and the reactionary monarchist petit-bourgeois. The rise of UKIP threatened to split the Tories, which would have severely weakened the main party of the ruling class. Hence, the promise of a referendum prior to the 2015 general election, which did nothing to solve the problem but led to the present chaos and the resignation of Cameron.

Crisis of the Tory Party

Overnight the whole situation was thrown into turmoil. Boris Johnson’s leadership hopes were sabotaged by his old friend Michael Gove, who stabbed him in the back. But Gove failed to win the nomination. The way appeared open for the reactionary Brexiteer Andrea Leadsom. Her victory would have immediately split the Tory Party. That could not be allowed to happen. In order to prevent an election the Tory Grandees forced Leadsom to stand down. The leadership was quietly handed over to Theresa May, a “safe pair of hands”.

Overnight the whole situation was thrown into turmoil. Boris Johnson’s leadership hopes were sabotaged by his old friend Michael Gove, who stabbed him in the back. But Gove failed to win the nomination. The way appeared open for the reactionary Brexiteer Andrea Leadsom. Her victory would have immediately split the Tory Party. That could not be allowed to happen. In order to prevent an election the Tory Grandees forced Leadsom to stand down. The leadership was quietly handed over to Theresa May, a “safe pair of hands”.

This exposed the deep rifts in the Tory Party. This time they had managed to avoid falling into an abyss. But although Mrs May was subsequently given a “coronation” as unelected Tory Prime Minister, the tensions in the Tory Party have not gone away and will re-emerge in the future as the wheeling and dealing over Brexit unravels. The entry of Theresa May into Number Ten, the Financial Times stated, “offered some hope that Britain has not gone completely mad.” But this relief will only be temporary. The whole situation is pregnant with instability.

In an attempt to mollify the discontent that drove the Brexit vote, May announced a new Tory vision “for a country that works for not just “the privileged few”. She then proceeded to appoint three leading Brexiteers – Johnson, Fox and David Davis – to senior posts in the Cabinet. Gove was ousted from the Cabinet and Johnson, who had insulted virtually every leading politician and head of state in the world, was brought in as Foreign Secretary.

This demonstration of “unity” would soon become the Achilles heel of the government. All Mrs May could say about Brexit was “Brexit means Brexit”. What kind of Brexit remains a complete mystery. Work would proceed on the negotiations after Article 50 was triggered in the spring of 2017. But the ranks of the Tory Party are pressing for a complete break with Europe, and the end to the free movement of labour, while others in the Cabinet are insisting on maintaining access to the Single Market, even if that means accepting free movement of labour. Unfortunately, the two propositions are mutually exclusive.

Immediately serious divisions were made apparent by the leaking of a secret memo. The leaked memo by Deloitte explained that the government has no overall Brexit plan and could need an extra 30,000 civil servants to deal with the complexity of the task facing the country. The memo, dated 7th November 2016, said that “divisions within the cabinet” were bedevilling Brexit preparations and that officials in different departments were being asked to work on 500 separate related projects.

There is no sign here of the clear-sighted preparations May talked about! Rather the whole thing appears to be in chaos, as different ministers and government departments constantly work against one another. Referring to frustrations, the memo says big businesses, in demanding certainties, could soon “point a gun at the government’s head” to secure what they need. Mrs May soon buckled. She announced at the CBI conference that the government’s agenda was “unashamedly pro-business.”

All bourgeois politicians say one thing and do the opposite. All the stupid talk of putting workers on boards and highlighting corporate greed at the Tory conference had not gone down well with big business. Therefore Mrs May quickly abandoned the idea, which was never going to happen in any case.

All that nonsense of “governing for the many, not the few” was soon forgotten. Mrs May made her position absolutely clear. “We believe in capitalism. And we believe in business”, she boldly announced to the CBI. “For if we support free markets, value capitalism, and back business – and we do – we must do everything we can to keep faith with them”. However, she did make a touching appeal to Britain’s top bosses to help her save capitalism by “avoiding corporate greed and other excesses”. Amen!

To moderate the effect of that sermon, she raised the prospect of cutting corporation tax on business to a mouth-watering 15%, a move that was far more to the taste of her audience. In addition, billions of pounds will be spent on new infrastructure to “get the country and business moving”, which will simply put more cash in their pockets. Here was an echo of the “guarantees” made to Nissan over its future investment plans in Sunderland.

Above all big business is fearful over the prospect of a “hard Brexit” and the potential loss of access to the Single Market. All May could offer was a hint at a transitional deal on Brexit. However, she was silent as to where such a transition would eventually lead. The government is trying to ride two horses at the same time. But the fudge over Brexit will not be passed over so easily.

The decisive section of the British bourgeoisie wants to stay in the Single Market at all costs, even if this means accepting the movement of labour, which it must. The Brexiteers on the other hand want to “take back control of our borders” and control immigration. The Cabinet is therefore split. Whatever they do will be seen as wrong and will have serious consequences in one form or another. There is no possibility of appeasing both wings.

The serious bourgeois strategists are alarmed by all this uncertainty and potential loss of markets, including access to cheap labour. In normal times, their interests are guaranteed, but these are not “normal” times. There are too many uncertainties that can upset the apple cart. As the Financial Times explained:

“This [process] will be subject of two sets of negotiations – the first with her own party, where the interests of business will collide with the ideology of Little Englanders, and then with the other 27 EU states. The former may be harder than the latter.” Her task is summed up as “squaring half a dozen circles.” The article concluded: “We are living through a period of political and economic upheaval – in Britain and in the rest of the continent.” We could add also in the rest of the world.

With fraught negotiations unlikely to be completed by October 2018, Mrs May is now thinking of a deal – a “transitional agreement” – allowing negotiations to string out for years in an attempt to kick the can down the road. But this is causing resentment. Any delay smells of betrayal to people like Nigel Farage, who has threatened to lead a popular revolt.

The Brexiteers will soon find that life outside the EU will not be as comfortable as they had hoped. After Brexit, Britain is fast losing its usefulness to the United States. Obama paid his final farewell trip to Europe, visiting not London, but Angela Merkel in Berlin. On top of this, American banks in London could be encouraged to relocate to New York, which will face even less regulation. Such an approach would tend to push the UK towards further cooperation with its European partners, only to find that Brexit has got in the way.

Boris Johnson hailed the victory of Donald Trump as “an opportunity” for Britain to get a favourable trade deal with the United States, overlooking the small detail that any trade deal with Trump must be to the advantage of America, not Britain. The so-called “special relationship” with Britain will count for less than nothing.

Trump’s election, rather than promoting British interests, is being very problematic, questioning the existence of NATO, demanding the Europeans shoulder greater military spending, talking up protectionism, and so on. Trump openly treats the British government with contempt. He personally called eleven other world leaders, including those of Ireland and India, before speaking to Mrs May. The real relationship was shown when the President elect met with Nigel Farage before any British minister. That was a public humiliation for Mrs May’s government.

Nor will May get a smooth ride in negotiations with the EU. The European leaders are not interested in the problems of the Tory Party in Britain. They do not wish to see the EU unravel and therefore will not want to make it easy or pleasant for the UK to leave for fear of setting an example to others. They have their own interests to defend, especially as they face the rise of anti-EU parties within Europe. The rules of Article 50 require consensus between all 27 countries on the terms of departure – making a good deal for Britain impossible. They will want to make it as hard and difficult as possible. Schauble, Hollande and Draghi have made this crystal clear.

Therefore, the UK could face a massive £100bn bill for Brexit over five years for the privilege of leaving the bloc. It has also been suggested that the UK will also need to keep paying into the EU budget for several years, all of which is like a red rag to a bull for the Brexiteers. “Until the UK’s exit is complete, Britain will certainly have to fulfil its commitments,” stated Wolfgang Schauble, Germany’s finance minister. “Possibly there will be some commitments that last beyond the exit… even, in part, to 2030… Also we cannot grant any generous rebates.”

These negotiations will therefore be very tough and very lengthy. This will only serve to entrench positions and poison the atmosphere, making things even harder. The Tory government will be pulled in all directions as it seeks to navigate between a rock and a hard place. This will open up all kinds of splits and divisions, as each step of the negotiations are leaked by either side.

With each new revelation, tempers will flare and the temperature will rise, making it even harder to reach an agreement. This in turn will be used by the Brexiteers to stoke up anger throughout the country. The people who voted for Brexit will feel increasingly frustrated and betrayed. With every prevarication, the government will become more and more unpopular.