The elections in Brazil on Sunday have brought to power Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right candidate, who promises to launch a full on assault against the working class. How was this reactionary figure able to win?

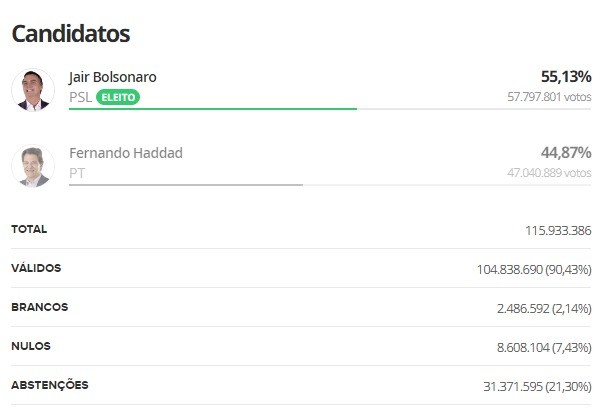

Bolsonaro won the second round of the Brazilian presidential election with 55 percent of the vote, defeating Haddad – the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate – who received 45 percent. Any hopes of a last-minute rally were dashed. This result is a setback for the working class and the poor. We need to understand what it means, what led to this situation and what strategy the workers’ movement should follow, faced with this reactionary government.

The second round of the presidential campaign was extremely polarised. There was a mobilisation from below on the part of the left in an attempt to stop Bolsonaro, and tens of thousands turned up at big rallies for Haddad in Sao Paulo, San Salvador de Bahía, etc.

In a taste of what is to come under a Bolsonaro government, the police, following orders from the electoral tribunal, waged a widespread campaign of preventing public meetings “against fascism” at universities and trade union buildings, removing anti-fascist banners from colleges and campuses and even sequestering trade union magazines. All of this was done in the name of “electoral fairness”, as these actions were considered to be “election propaganda” carried on outside of legal limits.

Emboldened by Bolsonaro’s rhetoric, there have been physical attacks on left-wing activists on the part of small fascist gangs, including the killing of Moa do Katendê, a capoeira master. These attacks need to be met with a bold response on the part of the workers’ movement, including the organisation of stewarding and self-defence of trade union and student meetings and the rejection of any form of censorship or curtailment of freedom of expression.

Brazil under Bolsonaro: a fascist regime?

However, those who today cry about ‘fascism’ having won in Brazil are mistaken. Fascism is a political regime based on the mobilisation of the enraged petty-bourgeois masses into armed gangs, with the aim of smashing working-class organisations. Historically, fascism came to power after the working class had been defeated during several revolutionary opportunities because of the lack of a correct leadership. On the basis of those defeats and missed opportunities, demoralisation set in and the fascist gangs were able to crush the workers’ organisations.

That is not the situation in Brazil today. Bolsonaro does not rely on armed fascist gangs. There are indeed fascist grouplets in Brazil, and they will be emboldened by his victory. They are dangerous and need to be met head on. But the Brazilian working class has not been defeated. In fact, it has not yet started to move in any significant way.

Let us remember that it is now two years since the election of Trump in the US. At that time, many liberal commentators and some on the left also talked about the victory of fascism in the US. Trump is certainly a reactionary politician and his policies represent an attack on workers, women, homosexuals, migrants, etc. But it would be a mistake to describe the situation in the US as a fascist dictatorship.

In fact, attempts by white supremacist groups in the US to take to the streets in the wake of Trump’s election were met with mass mobilisations that greatly outnumbered them. There has been a series of very militant (and victorious) teachers’ strikes in a number of states. There is a greater polarisation in society to the right – but also to the left.

What we are likely to see in Brazil is the continuation of a process (that had already started before the election) of bonapartist features appearing within the state. This was evident in the use of the judiciary as a political arbiter in the Car Wash scandal, the jailing of Lula and his disbarment from standing, etc. At the same time, the basis for a regime with bonapartist features is very weak, in conditions of severe economic crisis and widespread discrediting of all the traditional parties and institutions of the ruling class.

How could this happen?

Liberal commentators and some on the left look on in bewilderment at this election result. They cannot understand it. How is this possible? A far-right demagogue has been elected by democratic means. How could millions of people vote for someone espousing such odious views in such a brazen manner?

Liberal commentators and some on the left look on in bewilderment at this election result. They cannot understand it. How is this possible? A far-right demagogue has been elected by democratic means. How could millions of people vote for someone espousing such odious views in such a brazen manner?

They resort to all sorts of explanations that explain nothing: it was the fault of the networks around the evangelical churches, or it was the campaign of fake news on WhatsApp. This is the same as when the ruling class attempts to ‘explain’ strikes and revolutions as the work of ‘Communist agitators’.

Already, in the 1990s, in Brazil there was a huge propaganda campaign against Lula: “he is just a metal worker with no experience and no qualifications”; “he is a Communist”; “he doesn’t even have a university degree”. That, however, did not stop him from eventually winning the election, with 61 percent of the vote.

In Britain, we have seen an unprecedented campaign of demonisation against Jeremy Corbyn. The whole of the establishment has thrown the most outlandish and outrageous accusations at him (that he is anti-semitic, a friend of Hamas, a terrorist lover, a Putin puppet, etc). None of that has had much impact. On the contrary, his support has grown on the basis of his programme of renationalisation, free education, housing, etc.

As a matter of fact, the victory of Bolsonaro is a product of the protracted crisis of the Workers’ Party (PT). When Lula was first elected in 2002, he did so in the form of an alliance with bourgeois parties. He appointed Meirelles, a US-based banker, as president of the central bank, and he respected the agreements with the IMF and pursued a policy of fiscal austerity. He also carried out an initial counter-reform of the pensions system.

This is not the place for a full balance sheet of his government. But suffice it to say that it did not represent any fundamental challenge to the power of imperialism and the Brazilian ruling class. However, he was able to benefit from the relative stability that resulted from a period of economic growth.

When Dilma Rousseff was elected in 2010, the situation had already started to change. Her policies were similar to those Lula had implemented, but one step to the right. Her running mate was bourgeois politician, Michel Temer. She appointed the head of the landowners and cattle ranchers as Minister of Agriculture and an IMF official as her Minister of the Treasury. The main difference was that she was faced with an economic crisis rather than economic growth. On the back of the slowdown of the Chinese economy, the Brazilian economy went into a serious recession in 2014-16, from which it still has not recovered.

Already, in 2013, there were mass protests of the youth against the rise in transport fares, which were met with brutal repression by the regional governors, who had the full support of the national government. The 2013 “June days” reflected widespread opposition to the whole establishment by a growing layer of youth, but also workers. The PT, having been in power for over a decade, was seen as part of that establishment the youth were rising against.

Rather than change her policies, Dilma then announced a package of privatisations and austerity measures. The protests in 2013 were followed by mass protests in 2014 against the World Cup, which were also met with brutal repression. In order to deal with these protests, the Dilma government introduced a series of laws (on criminal organisations, anti-terrorism, and so on) that severely curtailed the right to protest and demonstrate.

The impeachment of Dilma

The 2014 election was a turning point in this process. Dilma managed to win in the second round on the basis of mobilising the working-class PT vote, on the grounds of fighting against the right-wing policies of the bourgeois candidate, Aécio Neves.

The 2014 election was a turning point in this process. Dilma managed to win in the second round on the basis of mobilising the working-class PT vote, on the grounds of fighting against the right-wing policies of the bourgeois candidate, Aécio Neves.

She betrayed her own voters, however, by proceeding to implement the policies Neves had advocated: austerity, cuts, privatisations and attacks on workers’ rights.

Her approval ratings, which had been over 60 percent in 2012-13, collapsed to just 8 percent in 2015 – the lowest for any serving president since the restoration of democracy. It was at that time, sensing her weakness, that bourgeois politicians in her government started to move to remove her from power through impeachment.

Then, when they saw the danger of Lula becoming a candidate and winning the election (given that many people remember him as having presided over economic growth, combined with his link with the historic, revolutionary traditions of the PT) the judiciary intervened with a corruption case against him.

Lula was found guilty, despite the fact that no actual proof was produced for the crime he was being charged with. Then they further stretched the limits of their own legality by preventing him from standing. Even at that time, however, while Lula was ahead in the polls, more people said they would vote for nobody than for him, showing a widespread rejection of the whole political system.

It can be said, therefore, that the PT government’s record in power – relying on the votes of the working class to stay in office and carry out capitalist policies in alliance with bourgeois parties – destroyed the party’s reputation and severed many of its links with the organised working class. This paved the way for the victory of Bolsonaro on Sunday.

Even when the bourgeois politicians were busy removing Dilma from power, the PT and the trade union leaders did not organise any serious defence. There were rallies and demonstrations, a lot of threats, but no serious campaign of sustained and growing mobilisation.

The situation worsened when the unpopular Temer government continued and intensified the attacks on the working class. There were huge “Temer Out” rallies and finally a general strike in April 2017. The Brazilian workers and youth showed their readiness to struggle, but their leaders did not lead or foster that struggle, and so all the potential for a fightback dissipated.

Of course, Bolsonaro cleverly used social media and the networks of the Evangelical churches to spread his message a combination of lies, half-truths, hysterical hatred of “PT-communism” and an appeal to “make Brazil great again”. These methods, however, only had such an impact because of the disastrous policies and track record of the PT in government.

There were, of course, other factors: such as the frightful economic crisis in Venezuela (in the last analysis, a result of the attempt to regulate capitalism rather than abolishing it), which was used effectively against the PT (whose leaders, however, had never really supported the Bolivarian revolution in the first place).

“Defence of democracy”?

The policy and strategy of Haddad in the second round was suicidal. While Bolsonaro made gestures – such as promising a Christmas bonus for recipients of the Bolsa Familia benefits – to appeal to the poorest voters who had supported the PT in the first round, Haddad shifted to the right, in a futile attempt to capture the so-called centre ground.

The policy and strategy of Haddad in the second round was suicidal. While Bolsonaro made gestures – such as promising a Christmas bonus for recipients of the Bolsa Familia benefits – to appeal to the poorest voters who had supported the PT in the first round, Haddad shifted to the right, in a futile attempt to capture the so-called centre ground.

In the first round, Haddad had presented himself as Lula’s candidate and Lula’s image was prominently featured in all the election propaganda material. In the second round, Lula was dropped from the pictures and the party’s red was replaced by the colours of the national flag.

Faced with an ‘anti-establishment outsider’, as Bolsonaro presented himself, Haddad thought he could defeat him by being the candidate…of the establishment! He presented himself as the candidate of democracy, appealing for the unity of all democrats (including the same bourgeois parties that had stabbed Dilma in the back).

The only way he could have recovered the lost ground would have been to wage a serious campaign denouncing Bolsonaro’s economic programme (privatisations, attacks on pensions and so on) and offering as an alternative the struggle to defend the rights and conditions of the working class on a clear anti-capitalist line. Instead, we had abstract appeals to defend democracy; for dialogue and understanding; and to “strengthen the constitution”.

There was already a very high level of abstention in the first round: 20.3 percent in a country where voting is compulsory, the highest since 1998. In the second round, it was even higher – 21.3 percent (31 million) – with an additional 9.5 percent (11 million) who voted blank or abstained. This shows a significant layer of the electorate reject Bolsonaro but could not bring themselves to vote for Haddad either.

Bolsonaro’s economic policies

Capitalist commentators are cheering on Bolsonaro’s victory and encouraging him to carry out his election programme of wholesale privatisations and a thorough counter-reform of the pensions’ system.

Capitalist commentators are cheering on Bolsonaro’s victory and encouraging him to carry out his election programme of wholesale privatisations and a thorough counter-reform of the pensions’ system.

“Markets have risen on hopes Mr Bolsonaro will deliver on his promises of economic reform, particularly an overhaul of Brazil’s costly pension system and privatisations of its state-owned enterprises,” said the Financial Times today. It then quotes from a Goldman Sachs note:

“Ultimately the administration faces the challenge of, through a combination of disciplined policies and structural reforms, accelerating the fiscal adjustment and boosting the animal and entrepreneurial spirits, to finally release the significant trapped potential of the economy.”

The ruling class judges any government according to one simple rule: how well it carries out its class interests.

A key turning point will come when Bolsonaro attempts to implement his programme, led by ultra-liberal ‘Chicago boy’ economist Paulo Guedes. He will face the organised resistance of the working class, which has not been defeated.

As with the Macri government in Argentina, Bolsonaro will face a wave of union action, mass mobilisations and general strikes against his economic policies. Furthermore, his position is not as strong as it seems, as he has to pass legislation through an extremely fragmented parliament where there are 30 different parties that he will have to make deals with.

The task now is not to give in to despair but rather to prepare for the battles to come. What is required in the first instance is a clear understanding of how we got to this point, so that the process of rebuilding a fighting, working-class movement can begin again.

There are also more general lessons to be learned from the Brazilian experience. Left-wing governments carrying out right-wing policies will only prepare the ground for the victory of reaction. You cannot fight the far right by appealing to the defence of the very same crisis-ridden, capitalist regime in crisis that gave birth to it.