This book charts the growth of Bolshevism in pre-revolutionary Russia. It begins with the birth of Russian Marxism through the ideological struggle with anarchist and reformist currents. The development continues through the founding of the Russian Social Democracy, its various splits, and the crystallisation of the Bolshevik and Menshevik tendencies.

The book explains the 1905 revolution in Russia and the role of the Soviet form of organisation. It follows the struggles of the Bolsheviks through periods of reaction and the first world war, before charting their emergence as the dominant force among the Russian workers and peasants in 1917, eventually leading them to the conquest of power.

Alan Woods wrote this book in 1999 as an answer to the various histories of Russia written from an anti-Bolshevik perspective, or its Stalinist mirror image. It sets out to disprove the various slanders spread about the Russian Revolution by so-called academics and historians who allege that the revolution was a coup, an accident of history, or simply as the work of one great man (Lenin).

The book uncovers the real history of Bolshevism as a living struggle to apply the method of Marxism to the specific situation in Russia in the early 20th Century. It is a work of historical materialism and a study of the revolutionary process. In particular this book contains many detailed and valuable lessons on methods and tactics for the building of a revolutionary party. The Bolsheviks carried through the greatest event in human history – the seizure of power by workers and peasants in Russia in 1917. Learning the lessons of how they built the party capable of leading this revolution is of vital importance for those fighting for revolution today.

Part One: The Birth of Russian Marxism

In the 1880s the Russian proletariat was in its infancy. The revolutionary intelligentsia therefore looked towards the peasantry as the main revolutionary force in society. However, despite its oppression, the peasantry has never been able to play an independent role in society. Nevertheless, a movement of mainly upper-class youths with confused ideas but boundless courage decided to ‘go to the people’, sacrifice everything, and commit to living a life among the peasants trying to incite them to revolution. This was the Narodnik movement.

The Narodniks were met with suspicion and hostility among the peasantry, so some turned to individual terrorism as a short-cut, aiming to spark the masses into action through propaganda of the deed. Russian Marxism was born out of an implacable struggle against this trend of individual terrorism. Plekhanov was the father of Russian Marxism, having studied the ideas in Germany. He set about building a small group to promote these ideas in Russia called the Emancipation of Labour Group, in the second half of the 1880s.

As the Russian working class developed throughout the 1890s Plekhanov argued that the Marxists must move from propaganda aimed at a small number of people, to agitation aimed at a wider layer. This was the only way to connect Marxist ideas with the growing workers’ movement. Work among a wider layer soon forced the Marxists to confront questions of how to fight national and racial oppression by the Tsarist state, including the oppression of the Jewish people.

The more successfully Marxist ideas began to connect with the movement in Russia, the more they were picked up and distorted or misunderstood by the Russian intelligentsia. This produced the phenomenon of ‘Legal Marxism’ which accepted Marxism in name, but in practice stripped it of its revolutionary content. At the same time the trend of ‘Economism’ arose, which rejected the political struggle in favour of a purely economic one. The rejection of the idea that a fundamental, revolutionary change – politically, economically, and socially – was needed in society was common to Legal Marxism, Economism, and the ideas of Bernstein in Germany, who thought he had ‘modernised’ Marxism.

To wage the struggle for genuine Marxism against these trends Lenin founded the Iskra newspaper in the first years of the new century and set about trying to clarify the political ideas and professionalise the work of the Russian Social Democrats. This was a serious battle, in which Lenin had to bend the stick very far on political and organisational questions to win his comrades over. Some of the organisational differences that arose at the second congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in 1903 were linked to this struggle, and provoked the split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Later these organisational differences developed into fully formed political differences.

Study questions:

- Why did the Narodniks look to the peasantry as the main revolutionary force in society?

- What was the “revolutionary voluntarism” of the Narodniks? How was it different to the terrorism of Narodnaya Volya?

- To what extent would it be true to say that “a terrorist is a liberal with a bomb”?

- What were the contributions and limitations of Plekhanov and the Emancipation of Labour Group?

- How did the working class in Russia develop numerically and politically before 1890?

- What argument did Plekhanov make in his article “All-Russian Ruin”?

- What was the significance of this argument in terms of the development of Russian Marxism?

- What was Legal Marxism? How was it similar to Economism?

- What relationship did these ideas have to the ideas of Bernstein?

- Explain the development and role of the Bund in the RSDLP

- Why was the founding of Iskra such an important step in the development of Russian Marxism?

- What was Lenin’s “unfortunate theoretical lapse” in What is to be Done?

- What was the nature and significance of the disagreements between Lenin and Martov at the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP?

- Why did Rosa Luxemburg write, in 1903, that Lenin tended towards “ultra-centralism” and “dictatorial methods”?

- In what way did the organisational differences between Menshevism and Bolshevism become political differences?

Part Two: The First Russian Revolution

The 1905 revolution was the ‘dress rehearsal’ for the October revolution of 1917. It was the first ever entry onto the stage of history of the Russian workers.

At the outbreak of the revolution the Bolshevik faction was very weak, politically and organisationally, with the Mensheviks in a stronger position. But neither the Bolsheviks nor the Mensheviks had much support among the workers. Under such difficult circumstances the Bolsheviks debated whether to work in the reactionary trade unions to reach the masses. Lenin emphasised tactical flexibility while maintaining resoluteness on questions of principle.

A priest called Father Gapon was thrust to the head of the growing workers’ movement in 1905. He was a contradictory and accidental figure who was pushed along by events. The workers pressed onwards to a general strike, but the Bolsheviks were still viewed with suspicion by the masses.

The Tsarist regime’s reaction to the strike was brutal, and this sparked the revolutionary movement in earnest. Consciousness changed rapidly, barricades appeared in the streets, and the Tsar began to retreat. The Bolsheviks were viewed more favourably by the workers and had to adjust their methods of organising accordingly.

The Tsarist regime tried to use the combination of carrot and stick to stop the revolution. Where concessions were granted, they were partial, and this provoked tactical debates among the Bolsheviks about how far to engage with the partial concessions. At all times, whether participating in reactionary unions or bourgeois democratic elections, the highest priority is the complete political independence of the revolutionary party.

The pace of events required the Bolsheviks to be agile and adaptable. But a layer of Bolsheviks, though self-sacrificing, were unable to adapt to a revolutionary situation having been working in the underground for so long. Lenin waged political war against this conservative, small-circle mindset.

The 1905 revolution saw the creation of soviets, which are enlarged strike committees, thrown up spontaneously by the movement. The revolution also illuminated the importance of the peasantry as an ally for the working class in their struggle to overthrow the autocracy, not least because much of the armed forces were made up of peasants. The Bolsheviks had to adapt to these circumstances.

In the end the 1905 revolution went down to defeat due to the lack of a revolutionary leadership capable of taking the struggle to its conclusion. This led to several weaknesses in the movement, which the Tsarist regime was able to exploit. But the experience was not wasted. The revolution taught a whole generation of workers and revolutionaries important lessons about the revolution process, without which future successes would never have been possible.

Study questions:

- Why was the Bolshevik party weakened in the year preceding the 1905 revolution?

- How well understood was the faction fight, by the party and wider membership, and what were the effects of this?

- What was “Police Socialism”?

- What question did it raise among the social democrats?

- What contradictions did Father Gapon’s character represent?

- How did the workers perceive the social democrats during the Putilov strike? Why?

- What does Marx mean by “whip of counter revolution”?

- In which way did Lenin’s attitude toward party membership change between 1903 and 1905?

- What does this reveal in terms of his approach to organisational questions?

- What tactical questions did the Shidlovsky commission raise for the Bolsheviks?

- Who were the committee men and why were they a problem?

- What was the difference between Bolshevik and Menshevik finances?

- What role did bank-robbing play? How might this pose dangers to the building of a revolutionary party?

- What is the relationship between workers, peasants, and soldiers in a revolutionary movement?

- Why did the Bolsheviks advocate “active boycott” of the Bulygin Duma?

- What are Soviets?

- Why was the 1905 revolution defeated?

Part Three: The Period of Reaction

As the revolutionary movement ebbed, the concessions that had been granted by the regime were discarded. Mass movements were replaced by individual terrorism and guerrillaism, especially in the countryside, and the offensive struggle for power was replaced by a defensive one against unemployment and for basic standards of living.

The revolution had pushed the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party closer together organisationally, but politically big differences remained. One of the biggest was the land question, which was essential if the peasantry was to be won as an ally for the workers.

Tactical considerations, such as whether to boycott a bourgeois parliament and how to respond when the Tsar closed it down, were rediscussed in light of the different objective situation in 1906-07, compared to 1905. Once again, the key emphasis was on an independent political line for the working class, who should rely on their own strength.

The Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in early 1907 saw heated debate between the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions, especially over what approach should be taken to the bourgeois parties. The Congress was won by the Bolsheviks, who pushed the Mensheviks onto the back foot for the first time since 1903.

The underlying political differences between the factions were rooted in their understanding of the nature and tasks of the Russian revolution: as a bourgeois democratic one, or a workers’ revolution. Questions of the development of Russian capitalism, and internationalism, were central to this debate.

By the second half of 1907 and into 1908 the reaction of the regime towards the revolutionary movement was in full swing. The fortunes of the Marxists reached their nadir, under pressure from all sides. Some of the Mensheviks in particular were so affected by this demoralisation that they wanted to liquidate the party and abandon the perspective of revolution.

Lenin struggled firmly against this liquidationism, and its subjective idealist philosophical justification which had become fashionable among the academics and intelligentsia. This struggle was so sharp, and the mood of demoralisation so infectious, that it even resulted in a split within the leadership of the Bolshevik faction itself during 1908.

The years 1908-1910 were the hardest for the Russian revolutionaries, above all Lenin, who was completely isolated even in his own faction. There were attempts at unity between different groupings, but Lenin remained intransigent on questions of political principle. Trotsky in particular was a strong advocate of conciliationism and pushed hard for unity between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, despite the obvious political differences, although Trotsky himself had nothing in common politically with the liquidators.

After 1910 the economic situation began to improve, the labour movement began to revive, and this breathed new life into the Party. A new revolutionary situation was brewing, and this time the position and prestige of the Bolsheviks was on a far higher level than in 1905.

Study questions:

- How did the Bolsheviks intervene in the struggle against unemployment, in comparison to the Mensheviks?

- What impact did the revolution have on the workers of each RSDLP faction?

- How did Lenin approach the land question and peasants’ revolt?

- What were the differences between Plekhanov and Lenin on the question of the boycott of the Duma?

- What effect did the conflict over Duma tactics have on the RSDLP?

- What happened to the first Duma? What were the positions of the Mensheviks and Lenin on this matter?

- What was Lenin’s attitude to guerrillarism? What are the risks of this tactic?

- What was Stolypin’s reform to ‘extinguish’ the revolutionary movement?

- What was Lenin’s position on participation in the second Duma?

- Which main political differences were raised between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks at the Fifth Congress?

- How did the period of reaction express itself in the intelligentsia?

- What was Lenin’s disagreement with liquidationism and the ultra-left Otzovists?

- What was the basis of Lenin and Trotsky’s disagreement?

- Why was the January Plenum futile?

- If Lenin knew a split was inevitable, why did the formal split not take place until 1912?

Part Four: The Revival

Lenin held firm to the idea that theoretical clarity and a politically independent tendency were the prerequisites for building a genuinely revolutionary party. Having gone through the failed attempt at unity, Lenin pushed for a clean break, as against the conciliationists who prioritised a big organisation over political clarity.

A clear revolutionary tendency was necessary to be able to conduct genuinely revolutionary work among the masses, which was the Bolshevik aim. Once the clean break and formal split was achieved after the Prague Conference of early 1912, Lenin considered this to be the re-birth of the Bolshevik Party.

April 1912 saw a huge strike wave, picking up where the movement had left off in 1907. Compared to 1905, the Bolsheviks now found themselves in a far stronger position. The upswing in the movement required a daily paper, and the Bolsheviks founded Pravda to meet that need. Unfortunately, the editorial board of the paper, including Stalin, adopted a conciliationist line towards the liquidators. Lenin waged a firm struggle against this.

The elections to the Fourth Duma resulted in the first ever Bolshevik deputies being elected, opening up questions of tactics and work in the parliamentary arena. These were debated hotly, and mistakes were made, but under criticism and direction from Lenin the Bolshevik deputies began making good use of their positions.

As the revolutionary movement continued its upswing the need for a clear revolutionary line became more apparent. The Bolshevik Duma deputies came under pressure from Lenin and the masses to distance themselves from the Menshevik reformists. They did this and thereby won more influence among the masses.

The strengthened position of the Bolsheviks subjected their political ideas and positions to greater scrutiny, especially on complicated subjects such as the national question which was emerging in a sharpened form in the Balkans around this time. Lenin wrote extensively on the national question, and debated figures like Rosa Luxemburg. The main aim of the revolutionary policy is to guarantee the unity of the working class internationally. Such a task requires strategy and tactics which cannot be worked out in advance according to a blueprint.

As the class struggle intensified and the war approached everything became clearer and sharper – the only outcome was revolution or reaction. The situation was ripe for revolution, but the subjective factor of a strong revolutionary party was lacking, although the Bolsheviks were making gains by leaps and bounds. Russian tsarism was more afraid of this revolutionary potential than of war.

Study questions:

- Why is theoretical clarity essential for mass work, especially under conditions of reaction?

- What happened at the Prague Conference?

- How did the Bolsheviks deal with agent provocateurs?

- What was the August Bloc?

- In what way was Pravda a ‘collective organiser’?

- Why did the Bolshevik deputies initially make mistakes in the Duma? What were the correct methods for this parliamentary work?

- Why did the Bolshevik deputies eventually split from the Mensheviks?

- What was Lenin’s position on the national question?

- What was Lenin’s approach to pacifism?

- What was the state of the Bolshevik party on the eve of the First World War?

- Why did there need to be an economic recovery for the class struggle to pick up again?

Part Five: The War Years

The outbreak of war in 1914 provoked a crisis in the Second International, with so-called Marxist parties around the world all supporting their own bourgeoisie, despite the clearly imperialist character of the war. This position was a product of the long period of capitalist upswing which affected the consciousness of the tops of the labour movement.

The war exposed all the political tendencies in Russia, with some Mensheviks including Plekhanov swinging over to a chauvinist position. The Bolsheviks didn’t entirely escape from disorientation but soon rediscovered their bearings and held the revolutionary line.

For Lenin, after the betrayals by Marxist parties all over the world, his chief task was the re-education and re-orientation of a small number of cadres. He did this by elaborating a position of ‘revolutionary defeatism’, emphasising the need to turn the war into a civil war, and the idea that the defeat of Russia would be the lesser evil. This contained an element of polemical exaggeration to hammer home the point to the cadres, but when connecting these ideas with the masses the Bolsheviks were more nuanced.

The war meant the decimation of the party and the arrest and trial of the Bolshevik Duma deputies. It caused some vacillation among leading Bolsheviks, some of whom tended towards pacifism. As well as some trends towards pacifism, Lenin also had to battle some ultra-left trends which rejected the struggle for basic democratic rights.

During the war the Bolsheviks were at pains to avoid any attempts by German agents to involve them in intrigues against the Tsarist government. At the same time they were driven underground by the regime. The only thing that allowed them to weather the storm was their solid core of well-educated and professional cadres. By contrast the war utterly disorganised the amateurish Mensheviks.

The Russian general staff were rotten to the core, and the army was ill-equipped and untrained. The Bolsheviks agitated among the soldiers as far as possible, many of whom were from a peasant background.

The Tsar could feel the ground shaking under his feet and so dissolved the Duma. This provoked even more protest and strike action. The crisis of the regime was revealed by the assassination of Rasputin. As the tide of class struggle began to turn the regime granted some concessions and the Bolsheviks debated to what extent they should accept them or push for more. Complicated tactical questions were involved.

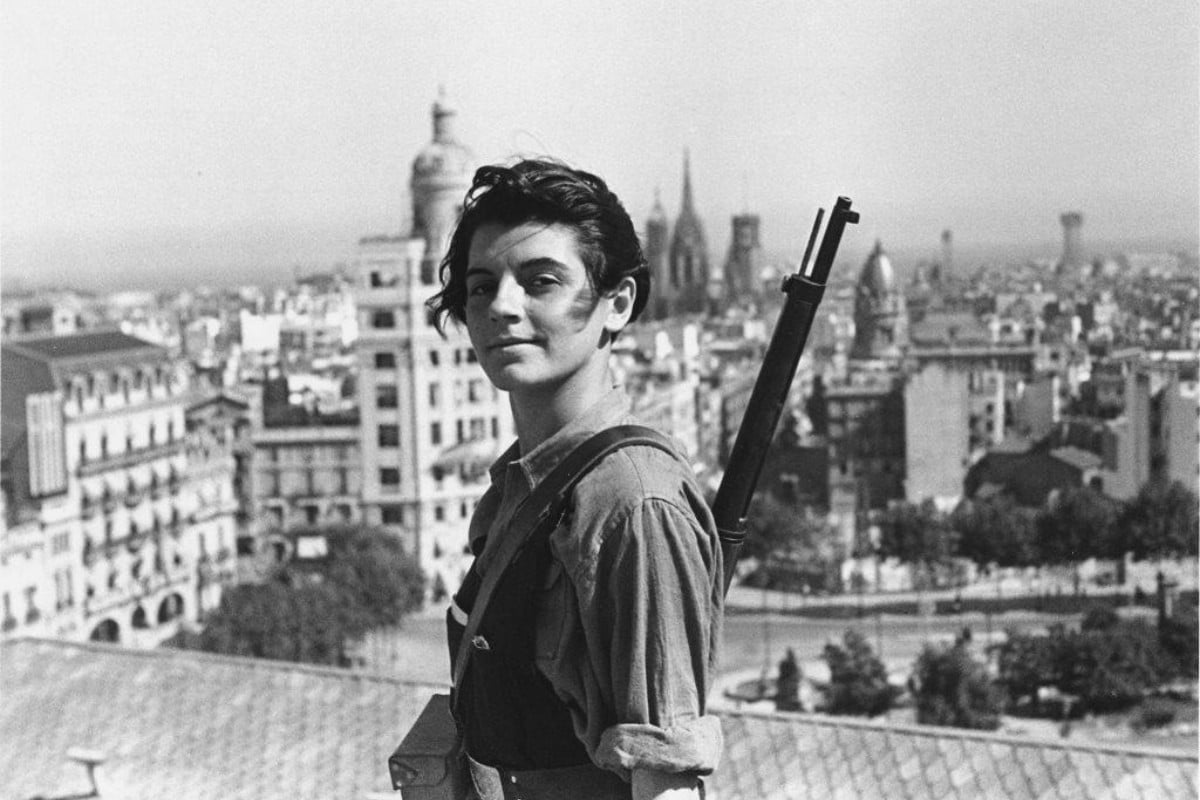

The Bolsheviks slowly began to rebuild as the mood among workers changed. They especially built among women workers, newly involved in the struggle. This work had nothing in common with feminism and everything to do with the fight for socialism through the unity of the working class.

The bankruptcy of the Second International led Lenin to call for the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915 to draw together the elements of a new revolutionary international. The conference attendees were a mixed bag politically, but it was a step forward in the struggle to crystallise a revolutionary current in the existing mass organisations around the world.

Study questions:

- What are the roots of social chauvinism?

- What were the various trends among the Russian social democrats in their attitude towards the war?

- What were the reasons behind Trotsky’s criticism of Lenin’s slogan: ‘turn the imperialist war into a civil war’?

- What pressure did the Bolshevik deputies in the Duma come under to clarify their position on the war, and from who?

- How do we answer the accusation that Lenin was a German agent?

- How did the Bolsheviks go from their disorganisation during the war to rapid growth and the seizure of power?

- What was the mood in the army after 1915? And what did the Bolsheviks do about it?

- What were the tactics of the liberals in the 1915 Duma?

- What was the Bolshevik attitude towards the war industry committees?

- Why and in what way was the question of unity on the left raised during the war?

- What was the significance of Rasputin’s assassination?

- How did the Bolsheviks agitate among women during the war?

- What was Lenin’s approach to the pacifists?

- What was the significance of the Zimmerwald conference?

Part Six: The Year of Revolution

A strike wave began in early 1917, and escalated to a general strike in Petrograd in February. The general strike poses the question of power. When soldiers were ordered to fire on the demonstrators they refused. This was the February revolution which overthrew the Tsar.

The workers had power in their hands, but were not sufficiently organised and conscious to carry the revolution through to the end. In fact, the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries simply propped up the liberals in the newly installed Provisional Government.

The February revolution caught the Bolsheviks by surprise and they had to adjust rapidly. The rank-and-file members of the party proved more revolutionary than many of the leaders. While the Bolsheviks were adjusting and consciousness was developing the Mensheviks had a head start and won the majority in the Soviets.

The situation was one of dual power with the Provisional Government and the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. This was an unsustainable situation because one acts on behalf of the capitalist class, and the other for the working class.

Independently and coming from different directions Lenin and Trotsky reached the same revolutionary conclusions and fought for them, against the vacillations of the Mensheviks and even some of the Bolshevik leaders, who offered support to the Provisional Government.

Lenin returned from exile in April 1917 and rearmed the party with the slogan ‘All Power to the Soviets’, with no support for the Provisional Government. The independence of the Bolshevik policy was more important now than ever.

Different layers of the Russian masses were moving at different speeds. The Bolsheviks tried to link these layers up with one another, which sometimes required the holding back of the most advanced layers to prevent them being isolated from the masses. This was the case in Petrograd in June 1917.

In July one wing of the ruling class backed a coup attempt by the reactionary general Kornilov. The Bolsheviks proved themselves the most resilient fighters against this coup, although they offered no support for the Provisional Government. The coup was defeated, but it caused the revolutionary movement to falter for a few weeks, only to return again on a higher level.

Throughout the year the Bolsheviks, who were in a minority in the Soviets, patiently worked to win over the masses through their slogans and their programme. Gradually their position of all power to the Soviets and no support for the Provisional Government was gaining ground, while the compromise position of the Mensheviks was losing support.

Winning the masses is 90% of a revolution, but the other 10% is a meticulous plan of action, which the Bolsheviks made. They set a date, won over the military garrisons, armed the workers, and legitimised the seizure of power in the eyes of the masses. So overwhelming was the support for the Soviets to take power that the old regime simply collapsed with hardly a whimper. There was no one left to defend the Provisional Government.

The insurrection was successful. The Soviets took power in October 1917. What followed was a bloody civil war and foreign invasion. The heroism, organisation and discipline of the Red Army was the key to victory, but international solidarity also helped defend the Russian revolution at that time. The Bolshevik party had been built from nothing into the force that carried through and defended the greatest event in all of human history.

Study questions:

- How did the February revolution begin?

- Why did it not result in the workers taking power?

- Why were the leaders of the Bolshevik party lagging behind the mood of the masses at various points throughout 1917?

- What is dual power?

- What is the significance of the slogan: ‘for the democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry’?

- What is the meaning behind the slogan ‘all power to the Soviets’ and how did it draw the working class towards the Bolsheviks?

- How did the Bolsheviks win over the peasantry to supporting the soviets?

- What were Lenin’s April Theses?

- What role did the Bolsheviks play during the June days, and why?

- How did the Bolsheviks respond to the Kornilov rebellion?

- What were the circumstances in which Trotsky joined the Bolshevik party?

- What tactics did the Bolsheviks use to guarantee the success of the insurrection?

- Was the Russian Revolution a coup?

- What, according to Rosa Luxemburg, is “the essential and enduring” element of Bolshevism?