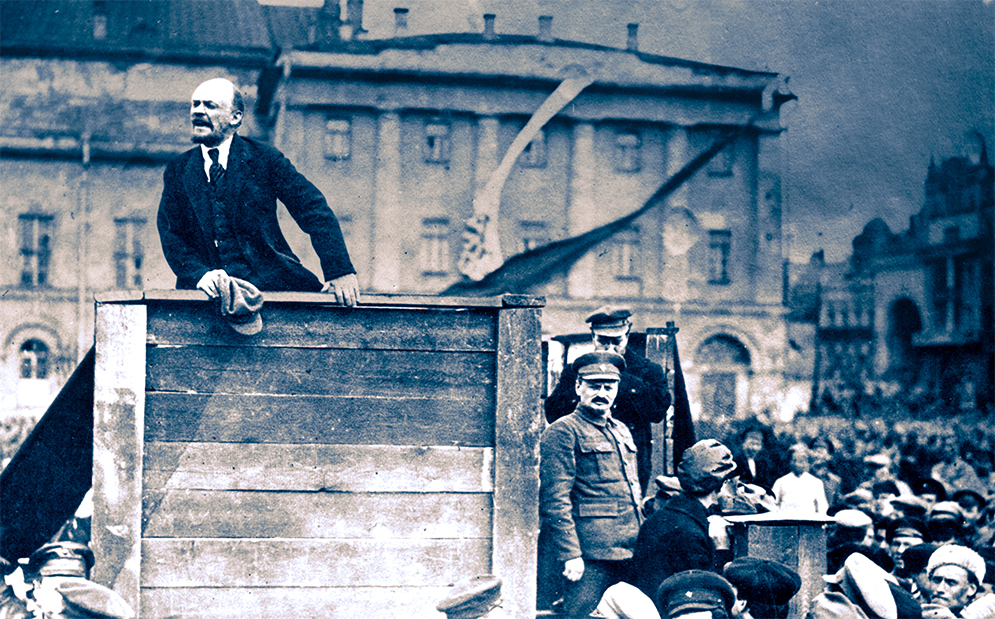

120 years ago, on a cold Sunday in 1905, tens of thousands of unarmed St. Petersburg workers marched to the Tsar’s Winter Palace to deliver a petition. When they arrived, tsarist soldiers fired into the crowd, killing hundreds and wounding thousands.

The events of that day, 9 January 1905 [Old Style, which is 22 January in the New Style calendar; all dates in this article are listed in the Old Style], went down in history as the Bloody Sunday massacre, and it marked the beginning of the Russian Revolution of 1905. It was on this day and in the months that followed that, for the first time, large numbers of Russian workers and peasants came to clearly understand that the Tsar was not and could not be their protector, but was one of their oppressors. At the same time, as they fought back, they began to realise their power as a class to change not only the conditions of their daily lives, but the whole world!

Background

Since the 1870s, Russia’s major cities had been undergoing rapid industrial development. St. Petersburg, Moscow, Baku, and others were becoming centres of concentration for a new industrial class, the proletariat. They concentrated within them enormous contrasts between the splendour and luxury of the elites and the poverty of the working people.

Russia remained by and large a poor, underdeveloped agrarian empire, with peasants making up the vast majority of its population. But amidst this backwardness arose these major cities, which were overcrowded, unhealthy, harsh centres of exploitation for the working class. Workers toiled eleven or more hours a day, six days a week, lived in cramped, uncomfortable conditions and performed forms of manual labour long outdated in more developed western capitalist countries.

For the tsarist government, these workers were little more than cattle. This attitude is vividly illustrated by the fact that, during this period, the tsarist government had a policy of deliberately getting the working and peasant population drunk with vodka – the state had an enormously profitable monopoly on the sale of vodka, and up until 1914, a full third of state revenue came from selling vodka to the working masses.

For years, many had rebelled against this state of affairs. Some tried to form small local trade unions; others even joined radical political organisations like the People’s Will (Narodnaya Volya) or the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). But, repressed by the vast tsarist police apparatus, these groups remained small and did not exert any serious influence on the growing mass of workers. At that time, the Social Democrats could only hope to reach a very thin layer of the most advanced workers. On a national scale, their forces were no more than a drop in the ocean.

A fateful day

In 1904 in St. Petersburg, dozens of worker activists under the leadership of a priest named Father Georgy Gapon, founded a workers’ organisation called the Assembly of Russian Factory Workers of St. Petersburg. Gapon was encouraged and directed by tsarist officials who wanted to create a reformist workers’ body that could channel the discontent of the proletariat onto the path of economic reform and away from political struggle.

In other words, the organisation had to be under strict control in order to keep the workers politically passive – for example, each meeting closed with the singing of the imperial anthem, “God save the Tsar”. This was known as ‘Zubatovism’, after its main conductor at the top of the empire, the head of the Special Department of the Okhrana (the secret police), Sergei Zubatov.

Despite the restrictions, Gapon’s organisation offered a means for workers to come together and organise in solidarity with one another, and by 1905 its membership had grown to at least 2,000. It was at this point that the workers’ themselves, responding to their harsh living and working conditions, pushed the organisation toward a more radical position, taking more of a fighting stance towards the tsarist regime.

On 3 January, a small group of workers were fired from the Putilov Iron and Steel Works, one of the largest factories in St. Petersburg. Gapon and the Assembly demanded their reinstatement, and a strike began. Initial demands, including an eight-hour day and better working conditions, gradually evolved into political demands, including the right to freedom of speech and assembly. By 7 January, 140,000 workers were on strike. The sweep and strength of the movement began to give workers a concrete idea of how they could exercise their power.

According to Leon Trotsky, in his brilliant and detailed analysis of the 1905 Revolution, it was at this moment that “the Social Democrats came to the fore.” By Social Democrats, he meant the Marxist RSDLP, the party out of which the Bolsheviks would later emerge. These activists helped draft the famous petition that the demonstrators attempted to deliver on 9 January.

The petition – in the most respectful tone – asked for various legal, political and labour reforms that would alleviate some of the suffering of the workers. It called the Tsar “sire” and begged him to protect them from the bureaucrats and employers who exploited them. In these poignant lines, the St. Petersburg workers described their situation:

“Sire! There are more than three hundred thousand of us here, yet all of us are human beings only in appearance; in reality, we are not recognised as having a single human right, not even the right to speak, to think, to gather, to discuss our needs, or to take measures to improve our situation.

“Any of us who dares to raise our voices in defence of the interests of the working class is thrown into prison or sent into exile. They punish us as if it were a crime to have a kind heart, a responsive soul. To pity a worker, a downtrodden, disenfranchised, tormented person, means to commit a grave crime!

“Sire! Is this in accordance with the divine laws, by whose grace you reign? And is it possible to live under such laws? Is it not better for all the working people of Russia to die, so that the capitalists and embezzling officials, the robbers of the Russian people, can live and enjoy themselves?”

However, despite its respectful tone, the petition demanded significant changes that, if accepted, would have called into question the very basis of the Tsar’s rule. In particular, it asked him to convene a Constituent Assembly that could usher in a new democratic era in Russia, in which the workers and poor peasants could at least have their voices heard. Clearly, the Tsar and the feudal lords could not allow such a concession.

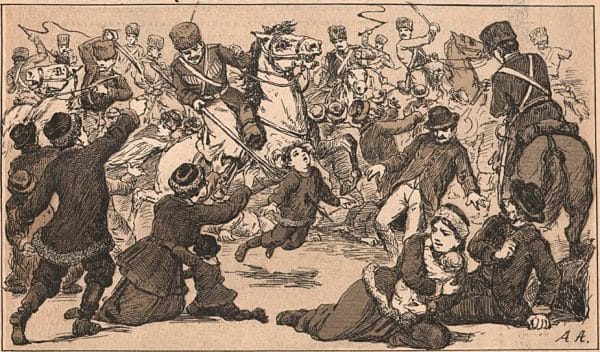

The petition, signed by 150,000 people, was never accepted by the Tsar. Instead, on 9 January, St. Petersburg police, troops, and mounted Cossacks attacked the unarmed demonstrators at various points in the city, shooting many in open squares and hacking them to death with sabres in cavalry charges. Estimates of the dead vary so widely that it is impossible to give an exact number. At least hundreds were killed and at least thousands were wounded in the hours of urban fighting in the Russian capital.

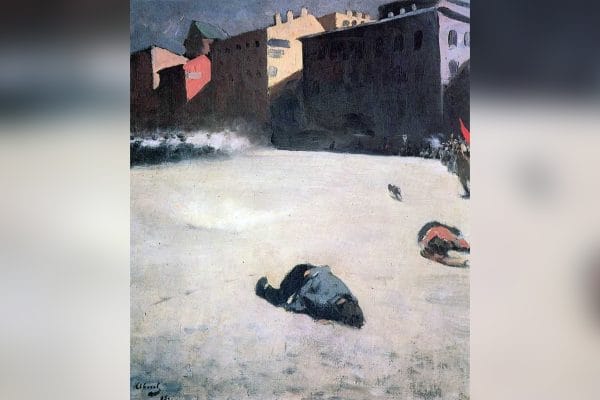

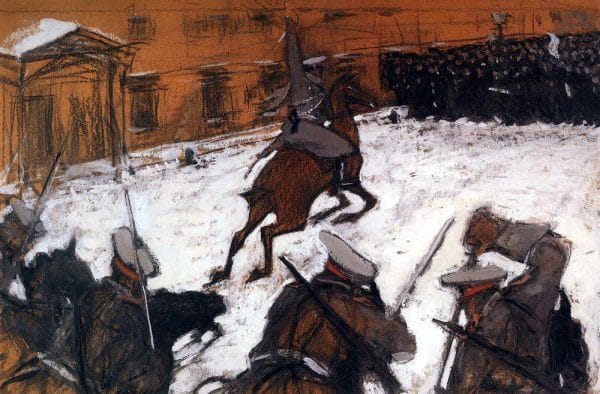

That day, Sunday 9 January, has since become known as Bloody Sunday. The violence that took place has become a symbol of the merciless exploitation and oppression that Russian workers and peasants have faced for centuries. The massacre left a profound impression on the lower and middle classes of Russian society. Having witnessed what happened on the streets of St. Petersburg that day, the artist Valentin Serov painted one of his most famous paintings, the title of which was imbued with bitterness, irony and a sense of deep disappointment: “Soldiers, brave boys, where is your glory?”

But it was also a turning point, the moment at which the masses could no longer accept their oppression, and were instead compelled to challenge their oppressors and fight for control of society. The massacre clearly revealed that the Tsar was one of their oppressors, no different from the powerful landowners or the rich factory owners who directly exploited them. Lenin wrote that “the revolutionary education of the proletariat has made a leap forward in one day that it could not have made in months and years of grey, everyday, downtrodden life.”

The enormous leap in the political consciousness of the Russian proletariat – who, in the course of a day, had gone from marching to the Tsar with icons in their hands, to organising a strike and rising up in armed struggle against the regime – came as a shock to the liberal intellectual public, who had declared the Russian proletariat “insufficiently mature” for revolution, as described by Leon Trotsky:

“‘The Russian worker is culturally backward, downtrodden and (we mean mainly the workers of St. Petersburg and Moscow) not yet sufficiently prepared for organised social and political struggle.’

“This is what Mr. Struve wrote in his Liberation. He wrote this on 7 January 1905, two days before the uprising of the St. Petersburg proletariat was crushed by the guards regiments.

“‘There is no revolutionary people in Russia yet…’

“These words should have been engraved on Mr. Struve’s forehead, if his forehead had not already resembled a tombstone, under which rest so many plans, slogans and ideas – socialist, liberal, ‘patriotic’, revolutionary, monarchist, democratic and others – always calculated not to run too far ahead, and always hopelessly behind…

“‘There is no revolutionary people in Russia,’ said Russian liberalism through the mouth of Liberation, having managed to convince itself during a three-month period that it was the main figure on the political scene, that its program and tactics determined the entire fate of the country. And before this statement had even reached its destination, the telegraph wire carried to all corners of the world the great news of the beginning of the Russian people’s revolution.” (L. Trotsky, After the Petersburg Uprising: What Next?, 2 February, 1905)

The aftermath

The massacre in the capital provoked a nationwide general strike that escalated into what is now considered the first Russian revolution. In the days and weeks following the massacre, word of the bloodshed spread, and the anger of the people exploded.

First, the city’s electricity workers went on strike. Then the printing workers. Then the sailors at the Kronstadt naval base. Finally, in October, a general strike began. The railroad workers spread it throughout the country. Then the miners stopped work, and so on. Marching from city to city, the general strike spread throughout the Russian Empire. The strikes would last a month or more, then die down, only to be followed by another strike a month or two later.

Leon Trotsky’s description conveys the wave-like development of the strike, which developed into full-blown revolution:

“The strike begins to confidently rule the country. Indecisiveness finally leaves it. Together with the growth in numbers, the self-confidence of its participants grows. Revolutionary demands of the class are put forward above the economic needs of the professions. Having broken free from professional and local frameworks, it begins to feel like a revolution – and this gives it unheard-of courage.” (L. Trotsky, Strike in October)

In the midst of these surging revolutionary waves, Russian workers became pioneers of a new form of organisation – the Soviets. These workers’ councils were created in early October as bodies that could unite workers of different professions and political parties into one body for the coordination of self-defence and strike actions. The Soviets were to represent only one class: the working class.

The first such body, organised in St. Petersburg, was called the Soviet (the Russian word for ‘council’) of Workers’ Deputies. It immediately got to work in organising the revolution, by calling for strikes, promoting communication between workers’ organisations, demanding policy changes from the city government, dealing with issues of food and goods supplies, making public statements on behalf of the working class, and organising the defence of factories and striking workers. Although many of the representatives were non-party workers, others were Mensheviks and Bolsheviks, members of the RSDLP. It was the first democratic, working-class body in Russian history.

By late 1905, however, the upsurge of the revolution was slowly fading under the pressure of a combination of tsarist repression, mild reforms, and exhaustion. In November, the members of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies were arrested and sent into exile. In December, the last workers’ revolt in Moscow was brutally suppressed, and the revolution of 1905 entered its twilight years.

The significance of Bloody Sunday

In spite of its defeat, the revolution of 1905 heralded the dawn of a new era. Not only had workers, peasants, and soldiers who participated in the revolution shed their old illusions about the Tsar, they had also witnessed their own colossal collective power in struggle against their oppressors and the repressive system that shaped their lives, and had developed powerful new tools for exercising it: the general strike and the soviets. Both would be used twelve years later, in the Russian Revolution of 1917. In fact, the experience of the revolution of 1905, and the lessons drawn from it, laid the foundation for the successful socialist revolution 12 years later.

The trigger for all of this was Bloody Sunday. The murder of hundreds of workers in St. Petersburg on that cold day violently awakened the proletariat, the peasants, and even the soldiers to an understanding of their position in society, their enemies, and – as they rose up, arms in hand – their own strength, which they would use to irreversibly change the world.