US Democratic Congressman Dennis Kucinich described the

$700bn bail-out of the US banks by the Bush administration as: “The largest

single act of class warfare in the modern history of this country”

In Britain £50bn is being doled out in a similar scheme.

That’s approximately £833 for every man, woman and child in the country, or

£1,500 for every taxpayer. If someone was to help themselves to £1,500 of your

money and spend it wouldn’t you at least want to know how and why? Yet the

language saturating the media is full of panic and obfuscation.

In line with the government’s wishes the BBC slavishly

described it as an “investment” in the financial sector. Everyone else is

calling it a bail-out. Far worse words have been used in private. Is the plan,

as the Chancellor says, all about “providing cash and investment for families

and businesses” or is this as Congressman Kucinich says, “An act of class warfare”?

Bad debts

We all know what bad debts are. If you lent a friend some

money you would expect it to be paid back. If they were to become elusive,

repeatedly forget to return it, or confess that they couldn’t afford to repay

you, you would have incurred a bad debt. You gambled on your friend being able

to repay you in the future and you lost.

Credit and debt is all about time. I may borrow to cover a

temporary shortage which I will repay when the shortage is over, or I may

borrow to help me make something, and I will repay my debt when the investment

pays off. All borrowing and lending is on the assumption that things will

change over time; a shortage will end or investments will yield returns.

Bad debts simply arise when this gamble doesn’t pay off. If

I borrow to build a business and not enough people buy my product, I run into arrears.

The bank acquires a bad debt. Likewise, if I borrow money to buy a house on the

assumption that my wages will cover it, only to find that interest rates grow

faster than my wages, I find myself unable to keep up my mortgage repayments.

Many households and businesses have found debts hard to

repay recently but the banks have been remarkably accommodating. The so-called

‘consolidation loan’ is a good example of this: people with multiple debts were

encouraged to take a single loan to pay them all off. The consolidation loan

would then reduce repayments to a manageable level. In effect, these schemes,

and many others devised by banks to ‘help’ their customers, postponed the

reckoning. They didn’t help businesses make products that would sell nor stop

interest rates and other expenses outstripping wages. They were simply, as the

old saying goes, throwing good money after bad.

As if this wasn’t bad enough it turns out that City traders,

like doorstep scamsters, have been dreaming up get-rich-quick schemes, selling

on debts to each other. Each transaction involves a little more speculation and

a little more slice of profit. With the jargon of these schemes they try to

bamboozle us, the same way they hid the bad debts from each other in the first

place. Among the ‘derivatives’, ‘futures’ and ‘options’ the real source of

profit and loss is hidden. We are meant to think that this is all too complex

for anyone but financial experts to understand, but it is all so terribly

important for the real economy that we should just ‘invest’ in them and shut

up.

In fact, a debt is a debt and there is no fundamental

difference between lending a friend a few quid and the massive loans made by

financial empires – apart from the amount of money involved. If a friend can’t

pay you back you might decide to let him off, or say “give me what you can and

we’ll call it quits”. Normal relations would be restored except that you would

be more reluctant to lend to your friend in the future. Why can’t the financial

institutions do the same thing, and what would happen if they did?

Market solutions?

Normally, when a debtor cannot repay their debt, the

creditor takes whatever the debt has been secured on. This is sometimes

referred to as ‘foreclosure’. When a business reaches this point, for example,

its premises and equipment are sold. The creditor takes the proceeds and cuts

their losses while the debtor is left with nothing. It is the equivalent of

‘paying what you can and calling it quits’.

In a market economy this is not as easy as it sounds.

A financial institution has no concrete use for such things as premises and

equipment, while rivals to the bankrupt business are powerful buyers. So these

things are sold off relatively cheaply, further devaluing bank assets. This is

why banks always prefer to reschedule payments. Only when the calculated loss

of doing this is greater than the cost of foreclosure are bad debts called in.

In the meantime debts accumulate.

When assets are finally sold off some businesses get bigger

by swallowing the previously indebted ones. But why take over a loss making

business? The predator takes a larger share of the market, reducing price

competition, and allowing it to charge more for the same services. It also has

what are called ‘economies of scale.’ For example, one business needs only one

reception, whether large or small. The process of ‘streamlining’ means that,

wherever there are two workers doing the same job, the business may be more

profitable with just one. One worker is made to work harder and the other is

made unemployed.

Because banks have been frantically lending to each other,

every bad foreclosure robs another loan of its security. In other words, if I

borrowed money from you, secured on a debt to someone else, and then wrote that

debt off, you would see my assets dwindling. It would pay for you to call in

your debt straight away to cut your losses. The longer you wait the less I will

have to give you.

So a problem for the banks and the financial system becomes

a problem for everyone.

A vicious circle of debt

default means job losses. Every lost job reduces the ability of individuals to

meet their debt repayments. A BBC journalist estimated that writing off bad

mortgages will mean around one million homes will be repossessed. No experts contradicted

him, nor pointed out that this is only the start. When businesses close jobs

are lost, and it should be no surprise that the unemployed find it harder to

repay their mortgages.

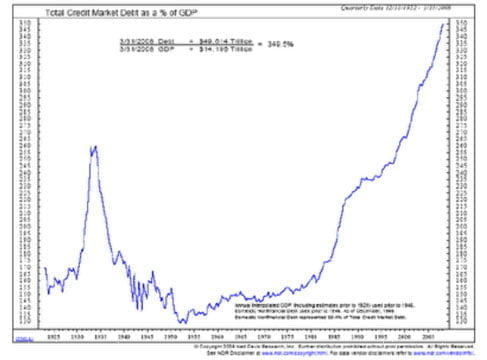

The net result of foreclosing on bad debts within the

The net result of foreclosing on bad debts within the

capitalist system is mass unemployment and economic slump. This would be the

free market solution. Last time it happened, whole economies disintegrated and

social conflict exploded. This graph shows the level of bad debt in the US

economy as a proportion of the economy.

The peak on the left shows the beginning

of the Great Depression, a period that produced the most horrendous Fascist and Stalinist barbarism and ended with a

World War. It is dwarfed by the current

level of personal and business indebtedness.

The Free Market

Everyone likes the word ‘free’. Any good marketeer knows

that associating it with any product will instantly get that product noticed.

That’s why the slogan ‘buy one get one free’ has replaced the old-fashioned

‘Two for the price of one’. Imply that something is free, even if it isn’t, and

the consumer is seduced.

A similar rule applies to ideology. That’s why the

‘freedom-loving’ people of the ‘free’ world have been subjected to so much talk

about free markets recently. For post-war capitalism the watchword was

‘progress’ – an ideal that could be taken any way you liked. But after the mid

1970s, when capitalism experienced its first global recession, new economic

theories came to the fore.

Characters like Milton Friedman, the Chicago School of

Economics and Mrs Thatcher and her acolytes sold an old product in a new

package. The product is simple: cut taxes for the rich, cut welfare for the

poor, limit the supply of money so that it retains its value and deregulate

everything you can. The theory says that the rich will invest more and direct

it to where it is most productive, so everyone will gain. The ‘product’ was the

looking after the best interests of the rich. The package was the ‘free market’

with the very idea of freedom thrown in.

Since the late 1970s governments all over the world have

tried to implement the theory. Wherever it has appeared to succeed, it has not

done so for the reasons claimed. Governments that deregulate and keep taxes on

the rich low can win investment at the expense of others. Ultimately

competitive deregulation benefits no one but the profiteers. But the process

helped to suck in and ruin weaker and less developed economies. It helped to

keep the global market opening up, as well as vastly expanding the flow of

credit.

In fact the ‘free market’ is only one part economic model,

and several parts ideology. It is a brand name that has been used to sell

welfare cuts, privatisation, attacks on trade unions and de-regulation,

blighting the lives of working people and driving millions, especially in the

so-called ‘developing world’ into absolute poverty.

On September 18th, when US Treasury Secretary,

Henry Paulson announced a plan to buy $700 billion of “illiquid assets” the

money markets rallied in support. Suddenly, the capitalists didn’t give a damn

about free markets. Why the change of heart? Paulson said it was to “save the

world economy”. How? By ‘recapitalising’ assets and injecting ‘liquidity’. It

makes it all sound like a technical exercise, like topping up the lubricant in

an otherwise well-balanced machine.

This marks the

beginning of a change in the dominant ideology of capitalism. While the

free market ideology said ‘the economy works as long as you don’t interfere

with it’, the new ideology says ‘the economy is too complicated for you, leave

it to us’

In fact, all these fancy-mouth phrases mean nothing more

than giving money to bankers. It is a massive dole out. It is what the American

documentary maker Michael Moore calls ‘Corporate Welfare’. In the US, where

free market ideology is most deeply entrenched, ‘welfare’ is used in the

reactionary media as a dirty word. It means living on other people’s money. For

years the sick, disabled, unemployed and impoverished in America have been

stigmatised by this label.

In reality it is the super-rich who have, even in the good

times, been living on other people’s money, more precisely on the unpaid labour

of the working class. The poorest have been thrown the crumbs, while the

super-rich have taken the cream. Now that the good times are over the veil is

falling, the so-called ‘free’ market turns out to be all packaging. The super-rich

came begging to the state. One of their representatives (Paulson) literally

knelt on the floor of Congress. The welfare cheque to end all welfare cheques

was handed over.

Given the choice between the free market solution of

foreclosing on loans, accepting that some gambles didn’t pay off and taking a

cut in profit, or looting the treasury to cover bad debts and carrying on just

as before: the capitalists chose the more lucrative option. The actual decision

was taken by governments, clearly demonstrating that they are not neutral

before the interests of the capitalist class. They say that our jobs are at

stake. But if that is so it just shows that the super-rich have the power to

hold us all to ransom.

Bowing to the overwhelming public distaste for the handouts,

both the US and British Governments have set conditions. The Chancellor

Alistair Darling explained them by mixing the stupidly obvious with the

obviously stupid. He said “you mustn’t take decisions that will damage the

economy” and that financial institutions would be advised to retain more

capital to minimise ‘systemic risk’”.

They agreed that Chief Executives who preside over failure

will not be rewarded. Their salaries will be capped at £400,000. There is

something seriously rotten at the heart of a system that can consider only

getting £400,000 a punishment.

Marx and regulated markets

Contrary to the claim made in a recent debate on BBC Radio

4’s Today programme, Karl Marx never “warned of the dangers of unregulated

market capitalism”. Marx was not a victim of the ideological trick that equates

capitalism with the free market. He spent the last decades of his life

tirelessly studying the inner workings of the capitalist system so that future

generations could use that knowledge to put an end to its self-evident

instability and injustice.

Banks gamble on the creation of value in the future. They

lent to households and businesses on the assumption that in the future they

would make and sell goods and services and hence have the money to pay them

back. While it is true that the crisis was caused by bad loans, commentators

who repeat this are simply voicing the financiers’ perspective. It is equally

true to say that the crisis was caused by the failure to produce real values.

Marx explained that capitalism spreads relentlessly across

the globe chasing new markets, that is, it makes and sells new things or sells

old things in new places. In this way it brings the whole world into one

interconnected system of production, trade and commerce, a phenomenon recently

rediscovered under the name of globalisation.

The financial system generates investment capital, that is

to say it extends credit, to exploit potential new markets. This capital looks

like real assets on paper, or on a computer screen: it can be converted into

hard cash and spent. But unless the new markets materialise and real value is

created it becomes fictitious capital, its value disappears as soon as you try

to realise it. Marx saw capital as the lifeblood of the system, and fictitious capital

as its inevitable product. He had no illusions that it could be regulated.

In that same radio debate a Bishop defended the Archbishop

of Canterbury’s attack on unregulated capitalism, but quickly distanced

himself, and by implication the church, from Marx himself, saying that Marx’s

very breath was corrupt. Consider for a moment how deep hypocrisy can get: to

hear such spite from a man who parades his fear of death in finery every

Sunday, and calls on the poor to seek their reward in the world beyond from his

privileged seat in this one: a world still mired in fear, war, hunger and

misery, and one in which allowing a big businessman no more that £400,000 a

year is considered a punishment.

The Bishop’s ugly slander not only shows how far the church

has diverged from the values of its founder, but also the contortions the

pillars of society are prepared to make in its defence. That Marx’s predictions

have been proved right and his conclusions sound is inescapable, the only way

to divert people from the next step, the solutions, is to spread mistrust and

confusion.

What Marx discovered working tirelessly (and in poverty),

over a century ago, is that labour is the source of all value, and that all the

credit notes, derivatives, futures, options and what have you, are ultimately

worth nothing without the production of real values by labour to back them up.

Furthermore the capitalist system depends on competition for

innovation and development. So it constantly increases the proportion of

expenditure on capital relative to labour, called the organic composition of

capital. This in turn causes the production of surplus value relative to the

value of the investment, that is the rate of profit, to fall. This is easy to

understanding by considering two businesses in competition with an equal share

of a market. An innovation, involving investment in capital, gives one business

a market advantage and extra profits. The other must compete by making the same

investment, restoring the equal market share. Now both businesses spend more on

capital, with no necessary change in the size of the market. The extra profits

have gone and the two businesses have an equal share of the market again, but

capital costs are higher.

Ways to offset the tendency of the rate of profit to fall are

to find new markets, borrow money in the hope of finding new markets, or

failing that, get a massive handout from the state. Marx also discovered that

the capitalists are not motivated by freedom or by any particular economic

model. They can pick up and discard ideologies like brand names. They are

motivated by class interests: in practice the defence of their power and

privileges.

Consequently there is nothing ‘free’ about the free market.

There is nothing remotely ‘free’ about capitalism. It is a system that ties

millions of people to the drudgery of unfulfilling, powerless jobs. It confines

millions more to abject poverty on the dirty streets of the 3rd

world. It allows 8 million children to die of hunger every year. It drowns

every voice of opposition in spiteful slander and unleashes brutality and

murder when it is threatened, as we saw in Bolivia only last September.

These things were all true of capitalism during the last

three decades of its most prosperous credit-fuelled boom. What does it have to

offer now? Now that the capitalists opted for the ‘bail-out and keep going’

option: not withstanding Alistair Darling’s helpful regulator permanently

dispensing advice on systemic risk?

Socialist solutions?

For many years socialists have been arguing for the

nationalisation of investment banking. The idea was regarded as impractical. As

of the middle of last month it suddenly became the only practical course of

action. It is worth considering how many other ‘impractical’ socialist ideas are

becoming more practical every day.

In the 1980s the

Conservative government under Mrs Thatcher saw an opportunity to roll back the

gains made by the working class on the housing front, while simultaneously

undermining Labour councils, stimulating the housing market and fostering the

illusion of a ‘property owning democracy’. She declared that council tenants

could buy the houses they lived in at a big discount. Such was the failure of

the Labour leaders to offer any opposition, or any alternative to the

inadequacy of existing ‘council housing’, that the Tories succeeded in their

massive sell off. Free from local authority tenancies, some working

class families gained more control over their homes and the freedom to move

home more easily.

As home repossessions climb in the coming period, there is a

danger that houses will be sold off to private landlords and more poor and

working class families will become tenants again, this time of worse landlords

than local authorities. While it is true that many private landlords on ‘buy to

let’ mortgages will lose their properties, their tenants can rarely afford to

buy them. So most small private landlords will be swallowed up by bigger ones.

By taking the properties of mortgage defaulters into public

ownership low rents could be charged, more direct democratic control could be

introduced and ways could easily be devised through democratic participation to

ensure rents could be transformed into assets. Rational systems could easily be

devised to allow tenants to move home even more easily than in a ‘free’ housing

market. A socially owned and democratically controlled estate agency would make

this possible.

Likewise, defaulting businesses should also be taken into

public ownership, rather than swallowed up by larger competitors. Many small

businesses with debt problems were originally set up by former workers who

wanted to be their own boss. This was a way of achieving more power in the

workplace. If they keep their job, but as an employee of a bigger firm, those

personal gains will be lost.

Socialism does not necessitate nationalising small

businesses. In most such businesses the owner is not privileged but is

exploited by landlords, money-lenders and the big businesses they are often

contracted to. Such small businesses could be helped to thrive by removing

these sources of exploitation and giving cheap credit from a social bank. Where

small businesses are unviable however, they can be merged and nationalised. The

former businessman need not lose their individual power and scope for

initiative in a system of genuine worker’s democracy.

None of these measures involve giving rich bankers any

money. In fact they would cost next to nothing. Even the administration costs

would be minimal, given the willing participation of workers keen to safeguard

their jobs. This is a considerable saving on the £50 billion currently being

spent by the government.

As the recession, which now even Gordon Brown admits is

coming, slips into slump unemployment will grow. The socialist solution is to

bring into social ownership firms that threaten closure or redundancies.

Productive work with a good income can be guaranteed because socially owned

firms can plan production for public good, get free investment capital from the

social bank and share work fairly on the basis of worker’s democracy. A socialist

employment service would eliminate unemployment by offering productive work

according to a worker’s needs and abilities.

Class warfare

The ruling class emerged from the crisis of the 1970s with

its new ideology of the free market. It seized its moment to reverse the gains

of the working class and enrich itself. This financial crisis is our moment. It

is an opportunity for the working class to fight back.

We need a leadership prepared to make the case for a

socialised investment bank, an improved social housing sector and more secure

employment in nationalised businesses. Yet such gains will not be made and

could not be secured without the direct action of the working class and the

abolition of a capitalist state that hands out massive welfare cheques to rich

bankers.

This £50 billion programme of massive corporate welfare has

nothing to do with ‘cash for families’ as Alistair Darling makes out. Such

things are incidental to the capitalists who are concerned only for their own

profits.

We commend Congressman Kucinich for his honesty when he

describes the bail-out as ‘class warfare’ but so far this is a one-sided war

conducted by the capitalist class against the workers. Who is going to fight

back?

Kucinich went on to say of his own party “The Democrats have

become unfortunately so enamoured and beholden to Wall Street that we are not

functioning to defend the economic interests of the broad base of the American

people. This is an outrage. This was democracy’s black Friday.”

Only a party of the working

class can adequately respond to an act of ‘class warfare’. A strong and well

organised party of Labour is essential.

But the lesson of Britain shows that a party of Labour

is not enough. The full participation of the workers is necessary to prevent

their party being used against them. The £50 billion bail-out is a criminal

act. It is such a blatant plunder of wealth by a parasitic class that even a

Bishop can see it. The Labour Movement needs a leadership that takes the fight

back to the capitalists: that understands the class nature of society and takes

the decisive steps to end it.