This year marks the 90th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. In the words of John Reed, "No matter what one thinks of Bolshevism, it is undeniable that the Russian Revolution is one of the greatest events in human history." We would say that, leaving aside the heroic episode of the Paris Commune, it was the greatest event in history because for the first time the working class actually conquered and held power, sweeping aside the despotic rule of the capitalists and landlords.

The strategists of Capital and their reformist shadows have attempted every year to bury the Revolution and to eradicate its real achievements and perspectives. It is not enough simply to defeat a revolution. They find it necessary, in the words of Carlyle, to bury it under a heap of dead dogs. For us, there are enormous lessons to be learned from the Russian Revolution. We therefore celebrate this key anniversary by publishing an article on the need for young people and trade unionists to study theory. Theory, after all, is the generalised experience of past struggles, above all revolutions and counter-revolution. How better can we prepare for the future? We need to learn the lessons of the past in order not to repeat the mistakes in the future.

Women and men enter into activity in the labour and trade union movement for a variety of reasons:

Careerism

For some, unfortunately in the past few years far too many, it has been and is a career opportunity. Just as anyone would embark upon a career in the civil service or in business, the fantastic salaries at the top of our movement are enough attraction to entice the careerists. As these individuals move upwards through the ranks of the movement, they become imbued with the "modus operandi", the way of doing things, of the organisation, be it a trade union or the Labour Party. Just as Marx said that conditions determine consciousness, so too these people begin to think like those who already hold top positions in the movement.

In addition, their mode of thinking is also conditioned by the lifestyle they have, due to the salaries they receive, which are often four to five times greater than the average wage of the members they are there to represent. When members are under the cosh from attacks on their wages and conditions, those at the top of the movement do not fall under the same pressures and are therefore increasingly less likely to understand the problems of the members, and are therefore less likely to initiate or support action to safeguard wages and conditions.

This is not to say that we, as Marxists, are against taking leading positions in the movement. We do so under specific conditions, for there are some in the movement who genuinely represent their members. We call for the regular election of all officers at all levels of the movement, with the right of recall if the job that they were elected to do is not done. That is democratic control. We advocate that officers should not receive a wage that is above the average wage of those they are there to represent, so that they do not lose touch with the members. We also demand that the democratic decisions of the members, arrived at democratically through national conferences, are carried out. How often have we seen the likes of Tony Blair, the man who constantly speaks of the need to defend and enhance democratic values, openly stating that he will ignore the democratic decisions of the Labour Party conference because he doesn’t agree with them?

We have become used to these kinds of careerists in the movement and we understand that they are a product of particular historical conditions, especially at times when the base of the movement has suffered defeat or has been lulled into a period of inactivity. Many of these careerists start with left wing credentials and then gradually turn to the right as they become enmeshed in the bureaucracy of the movement.

Genuine Activists

In the movement however there is another broad group who enter into activity because of an uncompromising hatred of the injustices of capitalism and a burning desire to see the creation of a more just, more equitable, more human way of conducting the affairs of human beings. This group is roughly divided into two categories:

Reformism

The first group is made up of those who believe, however genuinely, that it is possible to reform the capitalist system piece by piece until we reach the promised land. This group is very strong in the ranks of the movement and share some of the characteristics of the careerist group above. This is not to say that this group of genuine activists are careerists! It is to say that on the occasions when the ideas of reformism have taken hold of the labour movement, it has been at times of defeat of the movement after a revolutionary wave has been unsuccessful, or when there has been an upsurge in capitalist development resulting in the ability of the capitalists to distribute more crumbs to the working class. That is the ability of capitalism to grant reforms, albeit of a temporary nature, in order to buy the support of the working class or to stave off revolution.

Such periods were the 1950s and 1960s in Europe with the expansion of capitalism world wide on the backs of post-war reconstruction. Further back in time, the beginning of the 20th century produced the same results. An upswing of capitalism producing reformist illusions. Even the Conservative Party in the middle of the 19th and 20th centuries recognised that at times reforms have to be granted to gain the support of the working class. Unfortunately, in our movement there have been, and are, genuine activists who have been seduced by the ability of capitalism to sometimes "deliver the goods", and who therefore adopt the programme of reformism.

Revolution

In this second group, however, there is another wing, a revolutionary wing, that understands that reforms under capitalism are temporary and can be taken away at any time because the levers of power in society remain in the hands of the capitalists. This power consists of economic power through private ownership of the means of producing wealth: the factories, the land and the banking and insurance system. In addition, there is the state apparatus consisting of the armed forces, the police, the judiciary, the media, the education system etc., whose sole purpose is to protect the "status quo", and to prevent change that would harm the interests of those who own and control the wealth in society.

This revolutionary wing, small in Britain at the present time but growing in influence, is part and parcel of the labour movement and intervenes at all levels of the movement to protect and enhance the conditions of the working class, the creator of wealth in our society, but which also in the process of intervention constantly raises the issue of the need to disempower the capitalist class and fundamentally change the nature of society.

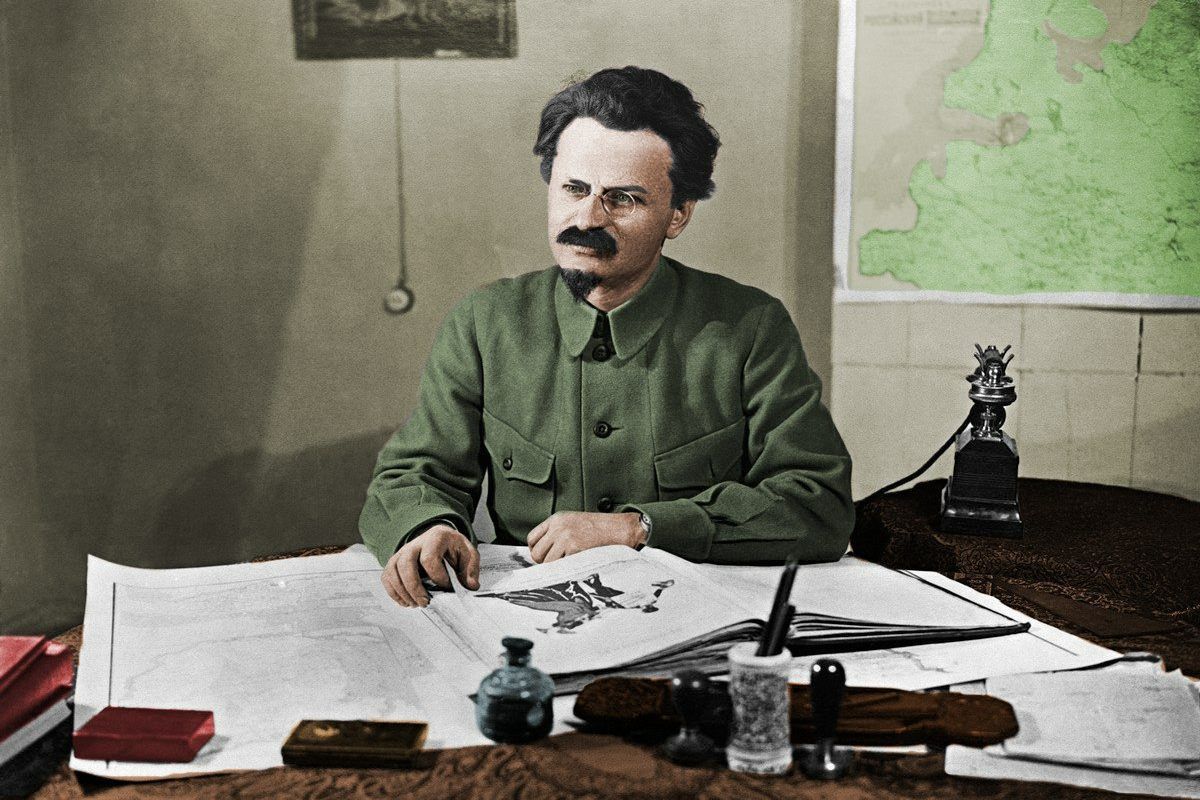

The major issue facing revolutionaries, however, is to understand when there are revolutionary possibilities for changing society and how to gain support for such changes. They must recognise that there is no blueprint for a revolution. Each revolution develops according to the specific conditions that exist in any society at any given time. This is not to say, however, that each revolution does not have features in common with other revolutions. If these similarities did not exist, then it would be impossible to work out beforehand the general line of development and therefore prepare the forces that will change society. It would also mean that we became empiricists, merely reacting to each particular circumstance that we came across with no plan or programme to confront that event. The contribution of all the great Marxist leaders: Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Grant and others, have been the recognition of the features that each revolutionary process has in common. What are they?

Common Features

Firstly, the inability of the class that owns and controls society to play any further progressive role in taking society forward. This class, in Marxist terms the bourgeoisie, has become a fetter on the development of the productive forces. Even more, this class itself feels under threat from a new class that is willing to take hold of the levers of power and change the nature of society. Such a threat leads to divisions amongst the existing ruling class as to how they can continue to keep their power and privileges. Such a situation leads to social and political instability.

Secondly, intermediate classes and layers in society, which, under conditions of relative normality, are quite content to give their support to the ruling class, either actively or through acquiescence, are now in the process of withdrawing this support and can no longer be relied on by the ruling class as a basis of social and political support. These intermediate layers, referred to by Marxists as the petite bourgeoisie, had been long convinced that their social well being lay in the hands of the ruling class and that their interests were synonymous with the interests of the ruling class. They had been deceived but were unaware of this deception. Now they are beginning to question where their interests really lie, and are seeking an alternative class that they can give their support to. This intermediate class does not play an independent role. It either supports the ruling class or the new class, in Marxist terms the proletariat, that is willing to fight for power and change society in the direction of socialism.

The third factor is the existence of a working class that sees no future for itself as a class under capitalism and is, therefore, ready and willing to take over the leadership of society, reorganise production to meet social need rather than serve the interests of parasitic shareholders, and in doing so begin the process of doing away with social classes themselves that arose on the basis of private property and the accumulation into a few hands of the surplus value created by the labour of the working class. When value is owned and controlled by society as a whole, and wealth is used for the benefit of the whole of society, there is no need for the existence of social classes.

These three factors, termed by Marxists as objective factors, have been described by the great Marxists as a result of studying in detail the processes of revolutions as they occurred since the death of one form of society, such as feudalism, and the birth of another system, capitalism. In addition, they have also studied in detail the revolutions that have challenged capitalism, some successfully and others not so. Marx’s work on the Paris Commune of 1871, Lenin’s writings on State and Revolution and Trotsky’s analyses of the 1905 and 1917 revolutions in Russia, stand out as classics that need to be studied by revolutionaries if they are serious about changing the nature of the society that we live in.

Study Revolutions

These analyses of past revolutions are an absolute must and are the principal reason why revolutionaries have paid so much attention to this question when educating activists. Without revolutionary theory distilled from previous revolutionary practice, there will not be a successful revolution. At the same time however the mere studying of revolutions without applying the lessons through work in the labour movement will condemn activists to revolutionary sterility. All talk and no action – and on the fringes of the movement there are countless examples of such revolutionaries!

There is more, however. Even after having studied revolutionary developments in various countries, it is not possible to transplant the lessons learnt word by word, letter by letter, to other countries. What is important is the method used to study these revolutions; the development of an understanding of the relationship between the crisis in the means of production, that is the inability of the present methods of creating wealth to take society forward, and its effects on the psychology of the classes that make up society. It is this understanding that is crucial if revolutionaries wish to intervene in the movement to build support for the ideas of socialism and therefore convince others of the need to change society. Such an understanding will enable revolutionaries to relate theory to reality, to outline possible lines of development and to advance demands that raise the consciousness of those participating in the movement.

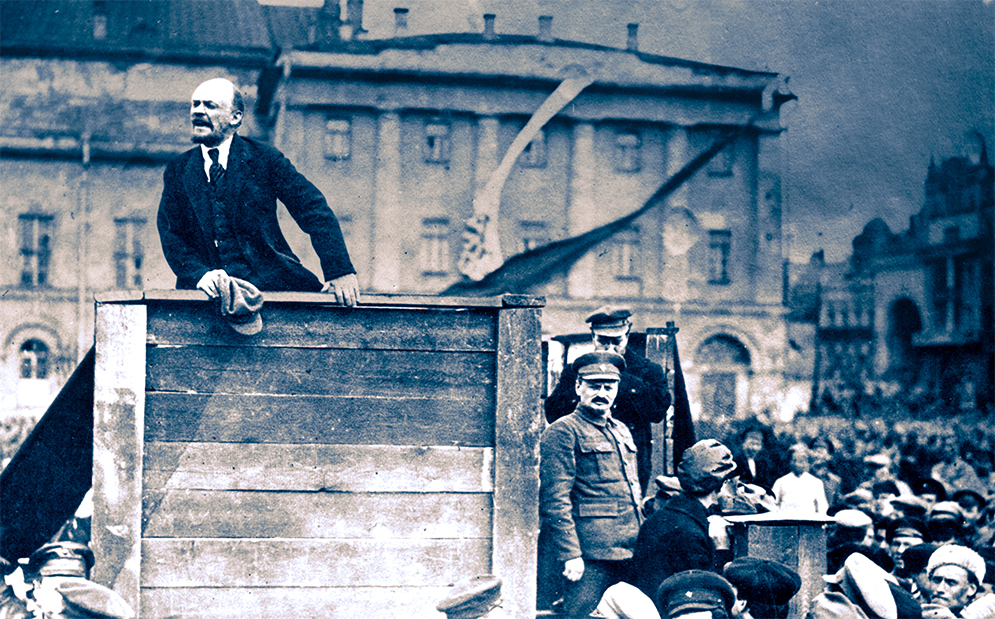

The Russian Revolution

For all who are serious in their activity, a study of Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian revolution is absolutely essential. Here, Trotsky lays bare the bancruptcy of Russian capitalism. He shows how modern methods of capitalist production created huge factories in the cities but that these existed alongside feudal property relationships of serfdom. He analyses the complete inability of the Russian ruling class to take society forward and to improve the conditions of the working class and the peasantry. He demonstrates how the social base of support for Tsarism, the peasantry, which made up the overwhelming majority of the population, is whittled away under the process of revolution. He also highlights the role of the working class, although comprising only 4% of the population, in alliance with the peasantry, as the only class that can take society forward.

In doing so he draws the conclusion that the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution – land reform, destruction of the economic and political power of the feudal aristocracy, the establishment of democratic rights, national independence, etc., – cannot be carried out by the weak capitalist class that is tied by a thousand threads to imperialism. These tasks can only be carried out by the organised working class which will not stop at the completion of these tasks but will go over to the socialist transformation of society as the only guarantee that these rights will not be removed by a counter revolution. And it is this class, the working class, that Marx called the gravedigger of capitalism. A class that is willing to fight to change society. A class that has nothing to lose but its chains.

All of these lessons are laid bare in Trotsky’s work. But the work also builds on the lessons drawn from previous great revolutionaries and from the Russian revolution itself. The mere existence of the three objective features outlined above is no guarantee that a revolution will take place, or if it does, that it will be successful. There is also the need for a fourth, subjective feature: the existence of an organised group of revolutionaries who understands the objective processes, as well as how different classes in society react to such processes, that is, the psychology of the classes. Such a group will have also sunk deep roots in the labour movement and be respected and listened to by organised workers because this group is a product of the day-to-day struggles of the movement combined with a theoretical understanding of how revolutions develop. When such a group is large enough to be counted in tens, if not hundreds of thousands, then it is a revolutionary party. Without such a party, which acts as the memory and general staff of the labour movement, a successful revolution will not be possible. This was the great contribution of Trotsky in this work, which should be studied by all activists who are serious about changing capitalist society into a socialist one as the only guarantee for the future of the planet and therefore of humanity.