The Grunwick strike was the first dispute where a majority

of strikers who were from ethnic minorities received widespread support from

the labour movement. Earlier disputes in Leicester and Southall had remained

marginalised, but in the 1970s the labour movement was regaining its militancy

and also taking up the anti-racist cause. The trades union movement stood at

11.5 million members.

A pamphlet and DVD

on offer from Brent Trades Council give an impressive outline of the extent of

solidarity that existed within the trades union movement at the time with

thousands prepared to attend mass picketing. It also shows the length that

employers such as George Ward at Grunwicks would go to in order to combat

trades unionism. In this he had the support of the courts, the Conservative

Party, the National Association for Freedom and the police.

Also it shows that the trades union leadership although

giving vocal support to the strikers were not prepared to support their members

until the bitter end, preferring to put their hopes in court action coming down

on the side of the strikers.

Grunwicks was a photograph processing factory in Brent,

North London, run by an anti-union employer George Ward. Previous attempts to

gain union recognition had been rejected and in August 1976 Jayaben Desai led

137 workers out on strike. They were soon all sacked. None of the workers had

ever taken strike action before.

They approached the

local Citizens Advice Bureau and APEX – their trades union which gave the

strike official recognition. These workers had never even been involved in a

trades union before but they were thrust into the front line of a nationally

acclaimed battle between the trades union movement and sections of the ruling class. They were to learn the

political lessons very quickly.

Solidarity action spread throughout the trades union

movement as the strike ran and ran and Grunwick became a household name.

Chemists were picketed and asked not to send photos for processing at

Grunwicks. George Ward tried to get this picketing outlawed but was

unsuccessful. Local postal workers, members of the Union of Postal Workers

refused to cross picket lines and deliver post. Calls however to cut off all

supplies of water and electricity to the plant were not supported by the

leaders of APEX or the TUC

The postal workers

also had to abandon their secondary action at the instruction of their union.

However Len Murray, general secretary of the TUC attended a packed meeting in

Brent.

Mass picketing began in

June 1977. There were 3,000 pickets. The police and Special Patrol Group

also turned up in force and there were 84 arrests. Scenes to become familiar in

the Miners’ Strike 1984/85 began to be seen on the streets of North London in

what was almost a civil war atmosphere.

On the 11th July 12,000 pickets blockaded the factory for

six hours including branches of the National Union of Miners from Kent and

Yorkshire. All this can be seen vividly on the DVD. In a controversial move the

pickets were called off at midday and marched around the town centre in Brent

allowing the strike breakers buses to go in.

The author of the pamphlet blames a compromise between the

strike committee and the leadership of APEX for this strategy. However mass

picketing would not have won the strike – secondary action like cutting off

power supplies to the factory could have done.

The Advisory, Conciliation and Artitratin Service (ACAS)

The Advisory, Conciliation and Artitratin Service (ACAS)

recommended union recognition following a ballot in March 1977 and the TUC

favoured a Court of Inquiry. The catch was – who was to be balloted – the

strikers or the whole workforce? George Ward refused to allow those inside the

factory to be balloted – they benefited from the industrial action by receiving

pay rises which would not otherwise be forthcoming. This catch allowed the Law

Lords to overrule the ACAS recommendation that the union should be recognised.

By the end of 1977

the strikers were getting desperate. The TUC had backed down from a call for

essential services to the factory to be blocked and APEX wanted an end to mass

picketing. This had become more bitter. On one day 8,000 pickets gathered

outside the factory and in the battles that took place over 243 were injured.

The Tory press turned against the strikers.

The strike carried on into 1978 and was eventually lost. But

it was not due to lack of solidarity or determination on behalf of the

strikers. They were let down by the right wingers in the leadership of the

trades union movement.

This pamphlet and DVD should be seen particularly by those

who did not live through the 1970s. It would be an eye-opener. For those of us

who did it brought back memories -both good and bad. The strike also gives a

different twist to the current debate about multiculturalism – there was no

doubt in those days that the strikers at Grunwick belonged in the trades union

movement, regardless of their ethnic background or culture. Workers from all

different cultures were united at Grunwicks.

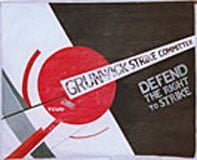

"Grunwick – bravery and betrayal:

a Brent Trades Union Council

pamphlet"

DVD – The Grunwick

Strike 1976-1978

Stand together 52 minutes

Look back at Grunwick 26 minutes

Available from Brent Trades Union Council, 375 High Street,

London

NW10 2JR