It was April 1968. I was sixteen years of age at the time. For

the previous two years, I had been an active member of the Swansea Labour Party

Young Socialists and a supporter of the Militant Tendency, after hearing Ted

Grant speak about the Russian Revolution.

In 1968 things had reached a very low ebb in the Labour

Party. Prime Minister Harold Wilson had succeeded in demoralising Labour

supporters after introducing a series of counter-reforms. The euphoria of the

general election of 1966, where Labour had won a landside victory, had

evaporated. As you can see, there are certain parallels with today. Many

radicalised young people had turned away from Labour towards the anti-war

movement, opposing the American intervention in Vietnam. It was part of the

general radicalisation that was taking place amongst students internationally,

reflecting itself in demonstrations and campus occupations.

However, revolutionary events in France were about to

transform everything in a big way. It also had a profound effect in Britain. Although

these events took place 40 years ago, I can still remember them clearly and the

enormous impact they made on me. The events of France in 1968 left an indelible

impression on the consciousness of all who lived through them.

|

| Rob Sewell, 1968 |

At school I had studied ‘O’ Level French and had been

corresponding with a pen friend living in Paris, who I had stayed with the

previous summer. Given the approaching Easter holidays I persuaded a school

mate to come and explore Paris for a couple of weeks during the school break. I

remember we arrived very late in to London and made our way to Kings Cross Station

where we were forced to stay the night. The experience was quite scary as we

were carrying enough French Francs to last us two weeks and Kings Cross was a

very seedy area. In the early morning, to our relief, we headed off to Victoria

to catch a boat train to Paris. When we finally arrived we managed to find a

scruffy boarding house near the Gare du Nord. After seeing most of the tourist sights

of Paris in the first week my friend decided to return home early, but I

decided to stay on and seek out a French friend Roland Ede who I had stayed

with the year before.

His mother and brother had gone away on holiday and he had

the flat all to himself. I could stay for as long as I liked. He took me to

visit various places, including the student cafes. There was always some new

experience in Paris. I remember he cooked a meal from horse meat, the first

time I had ever eaten the stuff, but it wasn’t bad at all.

Then one day he asked me if I was interested in attending a

student demonstration in the centre of Paris. Students were demonstrating

against the archaic education system. I was keen to see a French demonstration,

although I wasn’t expecting a huge turnout, judging from British standards. We

made our way on the Metro to a point where the march was due to pass by. As

with all major avenues in Paris the boulevard was absolutely enormous. I

wondered to myself what a small student demonstration would look like in such a

huge space. Not expecting much, my mind drifted back to the last May Day march

I attended in Swansea which had attracted no more that about 200 people. I

wasn’t paying too much attention, when I heard this faint but distinct noise in

the distance.

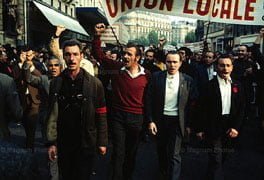

The noise got progressively louder and louder. I looked down

the boulevard. Then the noise got closer and closer. Suddenly, a huge wall of

people turned the corner filling the entire boulevard, waving red and black

flags flying, chanting and singing the ‘Internationale’. Wow! I was completely stunned.

I had never seen anything like it before. I was staggered at the large numbers involved

and this display of student militancy. A rush of excitement ran through my

whole body. It was a truly breath-taking sight. I will never forget it. Roland

and myself quickly joined the throng, caught up in the euphoria of the moment. We

shouted slogans and joined in the chanting as best we could.

Clearly, this was no ordinary student demonstration, at

least nothing I had ever experienced before. It had drawn into its ranks layers

who traditionally had never ever been involved. It was part of a general

movement of students, university and school, including demonstrations, strikes

and occupations that were serving to shake up French society.

As this huge demonstration moved through the streets of the

Latin Quarter heading towards the Arc de Triomphe, commotion broke out at the

front as police attacked the demo with tear gas and water cannon. Everyone

scattered for cover as the police waded in to the crowds, although many stood

their ground against the water cannons. Distraught students covered their faces

against the effects of the gas. It was a totally new experience for me. It

showed the state in its most brutal fashion. It was certainly far removed from

the placid Swansea May Day march that I was used to.

The next day Roland took me to Nanterre University, which

had become a hot-bed of student revolt. Students had taken over lecture halls

where continuous debates were held over student rights and demands. I was taken

into one assembly of a couple of hundred, which appeared pretty chaotic. The

air was thick with the stink of Gauloises’ cigarette smoke as speaker after

speaker put forward their arguments of how the struggle should be continued.

The whole situation was extremely politicised. Outside,

students swarmed around talking and discussing about the latest attacks. I met

a girl selling ‘Rouge’, a sectarian paper, who could speak English. While I

explained the need to turn towards the workers’ organisations, she based her whole

perspective on the student movement. All the French sects, which were much

bigger than those in Britain, had this view. They had no faith in the working

class. Others were distributing leaflets calling for student revolution. I

remember being hand an anarchist pamphlet, all of which were duplicated at the

time, explaining in detail how to make Molotov cocktails and other such bits of

useless information. It reinforced my impression of anarchists in their fantasy

world of conspiracy, black cloaks and bombs – completely divorced from the

struggles of ordinary working people.

Over the next few days I returned to Nanterre to meet

various left-wing students for discussions. None had any idea of what was to

come.

When I returned to London I visited the ‘Militant’ offices

in Kings Cross Road and told Ted Grant about my experiences. He was very

critical of the French sects, who had no orientation towards the working class.

“They have absolutely no idea”, he said, shaking his head.

It was only a week or so after returning to Swansea when the

news broke of a general strike paralysing France. Ten million workers had

occupied the factories and the country was in the grip of revolution. It was

the biggest general strike in history! In the short time I stayed in Paris I

could feel something was about to erupt. I vividly recall reading the ‘Sunday

Times’ with spreads of material including pictures about the ‘French events’. I

was full of expectation. Could this be the revolution we were waiting for? Was

a socialist society was finally within the grasp of the working class? The

monthly ‘Militant’ arrived with the banner heading ‘All power to French

workers!’ The French Revolution had begun.

Unfortunately, the opportunity was lost due to the cowardice

of the workers’ leaders. Nevertheless, as a sixteen year old, the French events

suddenly brought home to me the reality of socialist revolution and how we had

entered a new stormy period, which the tendency had predicted. Within a couple

of years, the Labour government had fallen and Britain entered a convulsive

period including a near general strike. The French events of 1968, after a

short delay, had even found an echo in Britain. Those days of 40 years ago will

return again. This time we can be better prepared. Without doubt, 1968 will be

forever remembered as a political turning point by all those who were touched

by those historic events. That was certainly my experience.