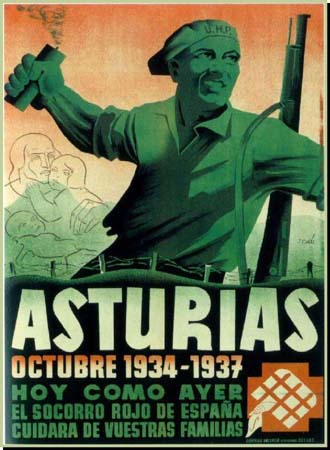

Yesterday (Monday 5th Oct) marked the 75th anniversary of the

Asturian Commune. The mining and industrial region of Asturias in Spain

witnessed one of the key revolutions of the 20th century. We want to

bring to the attention of our readers an article by Ramon Samblas written in 2004 for the www.marxist.com website and Socialist Appeal. For a more general analysis of the Spanish Revolution read Ted Grant’s The Spanish Revolution 1931-37.

70 years ago, the mining and industrial region of Asturias in Spain

witnessed one of the most fascinating revolutions in the history of the

20th century. During the course of 15 days men and women fought to

establish a new society free of exploitation and ruled by the

principles of workers’ democracy. This was the beginning of the

Asturian Commune.

On April 12, 1931 the Spanish masses voted massively for Socialist

and Republican candidates in local elections that took place throughout

the country. One of the main features of these elections was the high turn

out. Two days later, on April 14, the hated Monarchist regime

collapsed, the king was forced to flee the country and Spain became a

Republic.

The masses were seeking to end centuries of exploitation,

cultural backwardness and the influence of the almighty Catholic Church

in the economic and social affairs of the country. The bourgeois-democratic programme of land reform, development of industry,

the separation of the church from state affairs and the promises of

decent education and healthcare for all filled the Spanish peasants and

workers with hope. This situation opened up a period of

Socialist-Republican coalition governments and hope for the

historically oppressed masses in Spain.

However, by 1934 the bourgeois-democratic republic had shattered the

early democratic illusions and hopes of a big layer of the working

class and peasants. Three years after the proclamation of the

Republic, the working class was beginning to see that this Republic had

not solved any of the problems they faced. In the elections that took

place on November 19th, 1933, the workers massively abstained, and

together with manoeuvres of the bosses a shift to the right in

parliament took place. Lerroux’s Radical Party emerged as the winner,

but without an absolute majority. This meant they needed the support of

the CEDA, a far right bourgeois party. The CEDA was a far right party,

which represented landowners, “caciques” (direct political

representatives of the landowners in the countryside), army officers

and the bosses.

The situation in Spain became one of profound instability, which ran

through every section of the country, beginning at the top. One of the

main features of political life became the permanent crisis in the

cabinet. In the space of two years the cabinet changed 6 times, but the

Radical party (a bourgeois party which used a left rhetoric) was a

permanent feature of all these cabinets.

Another permanent feature of this period was repression. The

Republican-Radical government used laws that had been passed by the

Socialists when they had been in office (in coalition with bourgeois

Republican parties) against the very same Socialist Party! Between

November 1933 and September 1934 more than 100 issues of “El Socialist”

were sequestered. Prior to the 1934 uprising 12,000 workers were in

prison. The Socialist militias were banned and disarmed. The funds of

the trade unions were also sequestered. It was a cruel irony for the

Socialists; they were prosecuted with the same laws they themselves had

passed against, “wreckers and enemies of the Republic”.

It was becoming increasingly clear to the mass of workers that the

Republic could not fulfil their hopes and demands for a better life.

Experience had dashed their illusions in just three years. The

impotence of parliamentarism in the face of such a severe crisis of

capitalism was becoming increasingly evident.

The struggle against fascism and the impact on the workers’ organisations

This period was one of Revolution and Counterrevolution across the

whole of Europe. The 1929 crash had pushed this process even further.

Unfortunately, the Social democratic leadership, and the ultra-left and

sectarian policies pursued by the Communist parties, had led these

revolutions to bloody defeats and the triumph of Fascist and other

reactionary regimes. In 1933 Hitler had taken power in Germany. The

most organised working class in Europe had suffered a terrible defeat.

A similar situation unfolded in Austria. Years before, the Italian

working class had been crushed under the jackboot of Fascism.

The defeat suffered by the German and Austrian working class alerted

the rest of the European proletariat – especially the Spanish – to the

dangers of Fascism. Among the rank and file of all the workers’ parties

and trade unions a feeling of unity sprang up. Here we saw in practice

an example of how the working class, when it feels the need to

struggle, rejects splits and divisions as a general rule. The Spanish

proletariat was determined to defeat Fascism. They did not want to go

through the same experience as their German comrades.

The situation across Europe had the effect of pushing the parties of

the Second International to the left. This shift to the left was

initiated by the growth of the left wing within the PSOE (Spanish

Socialist Party). Largo Caballero and his supporters within the UGT

(Socialist trade union federation) and in the Socialist Youth even

stated they were in favour of the preparation of the proletarian

revolution. Even Prieto (identified with the moderate wing of the

party) stated in Las Cortes (the Spanish parliament) that he was

committed to preventing, by whatever means necessary – including an

armed uprising – a fascist regime coming to power. The pressure of the

masses on their leaders was pushing them further and further to the

left.

Largo Caballero illustrated the mood developing amongst the rank and

file of the workers’ parties. He had been a Minister of Labour during

the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1924-1930). In spite of that, in the

1930s his shift to the left was such that he became known as the

“Spanish Lenin”. However, the PSOE leaders were far from being Marxists

or Leninists. They replaced their earlier parliamentary cretinism with

an increasingly ultra-left policy. They suddenly declared they were no

longer interested in “bourgeois politics” anymore. Having abandoned the

idea of changing society slowly through parliamentary means, they now

failed to grasp the role that the platforms provided by the system

could play in the fight against capitalism.

The Revolutionary Workers’ Alliance

At the same time as a wide layer of the PSOE ranks was shifting to

the left a new phenomenon, the Revolutionary Workers’ Alliance (RWA),

was springing up all over the country. Its aim was to give expression

to the deep-rooted feeling of unity among the proletariat. In October

1933 the BOC (Peasants’ and Workers’ Block) and the Catalan federation

of the PSOE organised a rally appealing for the formation of a Workers’

United Front.

Later on, after the defeat suffered by the left-wing parties in the

November general election and the failure of the last Anarchist

uprising promoted by the FAI, a Revolutionary Workers’ Alliance was

created in Barcelona. The original committee consisted of the BOC, UGT,

PSOE (Catalan federation), FSL, Communist Left, USC (Catalan Socialist

Union), Unio de Rabassaires (Catalan small and medium landowners’

union), trade unions expelled from the CNT (controlled by the BOC) and

the dissident trade unions within the CNT gathered around Angel Pestana.

The Unio de Rabassaires and the USC withdrew from the Workers’

Alliance. The fact that both were giving support to the bourgeois

Companys government quite quickly brought them into conflict with the

original spirit of the Workers’ Alliance, which was that of a workers’

united front.

The first practical test for the Workers’ Alliance took place on

March 13, 1934. The Workers’ Alliance called for a strike against the

increasing influence of reaction in the central government. However,

the strike was called without appealing to the CNT (Anarchist trade

union federation). The CNT organised half of the unionised working

class in Spain at the time. The adventurism of the Workers’ Alliance

leaders and the sectarianism of the CNT leaders (especially in

Catalonia) prepared the ground for the defeat of that strike,

particularly in Barcelona. In general, the Workers’ Alliance failed to

be a real united front against Fascism.

The sponsors of the Alliance, the Communist Left led by Andreu Nin

and the BOC by Joaquin Maurin, never tried to unite the workers’

organisations at rank and file level. They always sought unity from the

top. This bureaucratic method undermined the whole project despite the

desires and mood in favour of unity against fascism within the rank and

file of the trade unions and workers’ parties. They failed to stand for

a Leninist policy on the united front – march separately and strike

together.

The sectarianism of the CNT leadership and the then tiny Communist

Party played a major role too. The Communist Party went so far as to

call the Workers’ Alliances “Reactionary Workers’ Alliances”. This was

in line with Stalin’s policy of the Third Period where the Socialists,

Anarchists and Trotskyists were denounced as Fascists.

Despite the opposition of the CNT to the Workers’ Alliance in

Catalonia the Asturian CNT leaders supported the idea of the Alliance

and they eventually joined it against the will of the CNT leaders in

the rest of Spain.

The explanation for the curious behaviour of the Asturian CNT is to

be found in the fact that the UGT and the CNT had almost equal forces

in Asturias. This situation had pushed the workers from the Socialist

and Anarchist trade unions to work together and fight together. For

instance, whilst the SOMA-UGT (Socialist mineworkers’ trade union)

dominated in all the pits, the majority of the metal workers were

organised in the CNT.

Historically, the Asturian labour movement had been the best

organised in Spain. The number of “People’s Houses” (social centres run

by the PSOE), Anarchist Social Centres, Cooperatives and even schools

run by the trade unions, is one example of how well organised the

Asturian proletariat was.

However, the process of drawing the CNT into the Revolutionary

Workers’ Alliance was not free from controversy and opposition within

the CNT itself. The stronghold of La Felguera controlled by the FAI

always opposed the Workers’ Alliance.

It is also important to remember the role played by the Communist

Party leadership. In the early 1930s the Communist Party had adopted

the ultra-left Stalinist idea of the “Third Period”, whereby the

Leninst tactic of the United Front was abandoned, which led them to

split the labour movement down the middle and facilitate the rise of

the fascists to power.

The mistaken policies of the Stalinist leaders led to defeats in

China (because of the Popular Front tactic), and in Germany and then

Austria (because of the sectarian “Third Period”. Through these various

zig-zags, by 1934, the Comintern had ceased to be a genuine

revolutionary International. Instead, as Trotsky explained, it had been

reduced to the role of border guard for the Stalinists in Moscow.

Later on, the Stalinists shifted to the right again and adopted the

tactic of the popular front. They changed their ultra-sectarian outlook

on the Social Democracy to one of class collaboration. Marxism explains

that ultraleftism and opportunism are two sides of the same coin. Both

policies resulted in catastrophe during the course of the Spanish

Revolution. In Asturias, on the eve of the uprising, the PCE (Communist

party) leadership dropped their definition of the Workers’ Alliance as

the “live nerve of counterrevolution” and instead applied to join it!

The pressure of events, and from their own rank and file, was becoming

too much for them to resist.

From the General Strike to the Revolution

By the end of September the crisis was so serious that the

Radical-Republican cabinet headed by Samper collapsed and in the early

October days, Alcala Zamora (the president of the Republic) called on

Lerroux to appoint a new government.

The ruling class did not have a real way out. There was also

mounting anxiety and tension amongst the working class. Everybody was

waiting to see whether Lerroux would give any ministries to the CEDA.

The working class regarded the entry of CEDA into the new government as

the first step towards Fascism in Spain. The German experience was

fresh in their minds. On October 3, Lerroux appointed three CEDA

ministers. Six hours later the UGT and the Workers’ Alliances called a

general strike.

Despite the shortcomings of the leadership – their failure to call

on workers to occupy factories and peasants to seize land, and the lack

of real soviets and clarity – the working class threw themselves into

the fight.

In the end the general strike was doomed by the lack of

participation of the workers of some key sectors of the economy

organised by the CNT, such as the railways. This allowed the

transportation of ammunition and troops to crush the protest. The

workers did not receive arms until hours after the public

appeal for the general strike. The Army used this time to arrest

workers and disband militias. But, the workers resisted with the

general strike going on for days and industry and trade were paralysed.

In spite of the limitations of its leadership, when the working class

starts to fight with such determination, it cannot be easily stopped. A

ferocious struggle ensued. However, in the end, the failure of the

leaders was decisive and the movement was defeated.

The failure of that movement was analysed by Leon Trotsky. In his article The consequence of parliamentary reformism, in which he stated:

“The Socialist Party, like the Russian Social Revolutionaries and

Mensheviks, shared power with the republican bourgeoisie to prevent the

workers and peasants from carrying the revolution to its conclusion.

For two years the Socialists in power helped the bourgeoisie

disembarrass itself of the masses by crumbs of national, social, and

agrarian reforms. Against the most revolutionary strata of the people,

the Socialists used repression (…). When the Socialist Party was

sufficiently compromised, the bourgeoisie drove it from power and took

over the offensive on the whole front. The Socialist Party had to

defend itself under the most unfavourable conditions, which had been

prepared for it by its own policy”.

Trotsky pointed out that as a result of the previous parliamentary

cretinism of the Socialist Party, anarcho-syndicalism was strengthened

as a tendency within the labour movement and it drew towards itself the

best militant layers of the proletariat.

Nevertheless the role of the Anarchist leadership was as pernicious

as the social democratic leadership. They refused to support the

insurrection led by the Socialists. The insurrection is a decisive

moment, not a game, and it must be skilfully used and prepared.

Again Leon Trotsky: “Marxism is quite far from the thought that

armed struggle is the only revolutionary method, or a panacea good

under all conditions. Marxism in general knows no fetishes, neither

parliamentary nor insurrectional. There is a time and place for

everything.”

The worst betrayal of the movement took place in Catalonia. Lluis

Companys (Catalan Premier) feared the workers more than the troops sent

by the Republican government. He used the divisions within the labour

movement in Catalonia (especially in Barcelona) to proclaim the “Estat

Catala” (Catalan state). The President of the Generalitat appealed to

the Catalan people to calm them down. When the troops arrived from

Madrid and surrounded Barcelona, he just surrendered without

resistance. Of course, this “Estat Catala” did not challenge private

property nor the current social establishment. The Catalan bourgeoisie

was attempting to divert the attention of the masses through this

manoeuvre. Leaving the leadership of the struggle in the hands of the

petty bourgeoisie represented by the ERC (Catalan Republican Left) and

the Unio de Rabassaires proved to be a grave mistake.

This manoeuvre of the Catalan petty bourgeoisie could have been

overcome, but the CNT leadership dismissed the general strike as

“political” and did not join the movement. In a decisive moment, the

CNT that organised the majority of the Barcelona proletariat provided

no leadership. As dialectics explains, nature abhors a vacuum. This

vacuum was filled by the petty bourgeoisie led by Companys who did not

hesitate to betray the movement. In spite of this the Madrid government

“rewarded” Lluis Companys by jailing him and sentencing him to death,

which was later commuted. With the failure of the insurrection in

Catalonia the struggle in the rest of the country was seriously

undermined.

UHP! (Proletarian brothers and sisters unite!)

In Asturias, however the situation was completely different. Here

the General Strike took the form of an armed uprising. Only hours after

the armed uprising began important mining areas like Mieres were under

the control of the revolutionary workers. In two days the revolutionary

workers took over the Oviedo council, the Asturian capital. The

Workers’ Alliance had been established more than a year earlier and was

a real united front.

As explained before, the pressure of the workers on the leadership

in Asturias made them unite whether they wanted to or not. For

instance, the PCE was forced to join the Workers’ Alliance despite the

sectarian and ultra-left position of the leadership on this question.

The mineworkers led by Gonzalez Pena and Grossi were clearing the way

ahead with barrels of dynamite due to the lack of arms and ammunition.

The revolutionary Asturian proletariat was making up for the lack of

means and experience with their class instinct and creativity.

While the workers and peasants were establishing a new order called

the Commune, the institutions of the capitalist system were collapsing.

The Civil Guards and the Assault Guards were fleeing from the barracks.

When they saw the armed workers, some of them even joined the

proletarian army. The case of lieutenant Torrens is one of the most

famous. He surrendered his squad of Civil Guards and joined the workers

as a military advisor.

The Workers’ Alliances and the bodies which emerged from them (like

the Revolutionary Councils) during the revolution, acted as real

soviets. Despite the failure of those organisations in the rest of the

country, in Asturias they led the revolution.

During the 15 days of the Asturian Commune, the Revolutionary

Councils seized land, occupied factories, put the enemies of the

working class on trial through the Revolutionary Tribunals (a right

that reaction never conceded to the Asturian workers following the

repression of the Commune), established Workers’ Democracy and held off

the Moorish troops and the Legion, the two most reactionary bodies of

the Spanish army.

In spite of the courage of the Asturian masses the movement faced

serious problems. On the one hand the insurrection was isolated to

Asturias. This made it easier for reaction to defeat it. But the lack

of coordination of the different areas where the uprising was taking

place also made it very difficult for the militias to overcome their

lack of ammunition and weapons.

The failure of the insurrection in the rest of the country made it

possible for the Republican government to focus their efforts on

smashing the Asturian Commune. It became a common saying that if three

Asturian Communes had taken place, the Revolution would have been

successful throughout the country. Instead of the greatest of victories

there was the most terrible of defeats.

Repression was horrific. The Republican Army, led by Franco, did not

hesitate to use aerial bombing against the civil population. They also

sent thousands of troops to kill, rape and torture women and children.

These are the brutal methods that the ruling class used to crush the

Asturian uprising. They could not allow the workers and peasants to

decide their own fate. There are no exact figures, but different

sources calculate the numbers killed as 2000-4000. The people in jail

were counted in tens of thousands.

Once again, the lack of a clear programme and tactics proved to be a

disaster and the working class paid for it. If a genuine Bolshevik

leadership in the Socialist and Communist party and the trade unions

(both anarcho-syndicalist and Socialist) had led the revolution

throughout the country, the result would have been substantially

different.

But the sacrifice of the Asturian workers was not completely in

vain. They did prevent the rise of Fascism through parliamentary means.

The ruling class could only impose its open dictatorship after a 3 year

long civil war in which the Spanish workers fought like lions despite

being led by lambs.

We wish to pay homage to the struggle of these men and women who

bravely fought for a better world. They showed to the workers and

peasants of the entire world that a society without classes is

possible. Once again we reclaim the motto of the Asturian Commune

against capitalism, Unios Hermanos Proletarios! (Proletarian Brothers

and Sisters Unite!) UHP!

(Article first published in 2004)