Time and time again we are told that humankind is inherently selfish; that people are not interested in sharing with others and that a more equal and caring society, where people treat each other fairly and respectfully is a utopian ideal that can never be realistically achieved. What lies behind this is the idea that capitalism, with its free market economics and dog-eat-dog morality, is the most natural and practical economic system.

Is it true then that we are doomed to live in a state that resembles nothing more than barbarism – an unstable economic system that will forever go through booms and busts, with the dictators passing their money around amongst themselves while the vast majority of mankind has to suffer for it?

The world of art, cinema and music, however, show us many things that contradict the idea that people are self-centred and care nothing for unity and human solidarity.

Freed from the fetters of feudalism

Capitalism emerged from feudalism, a system of perpetual war between lords and monarchs over land, where the Church was the dominating political and ideological force of Europe and people accepted their God-given place in the world without question. The bourgeoisie in its early stages played a progressive role. It was the class that was responsible for bringing mankind out of the oppressive feudal system.

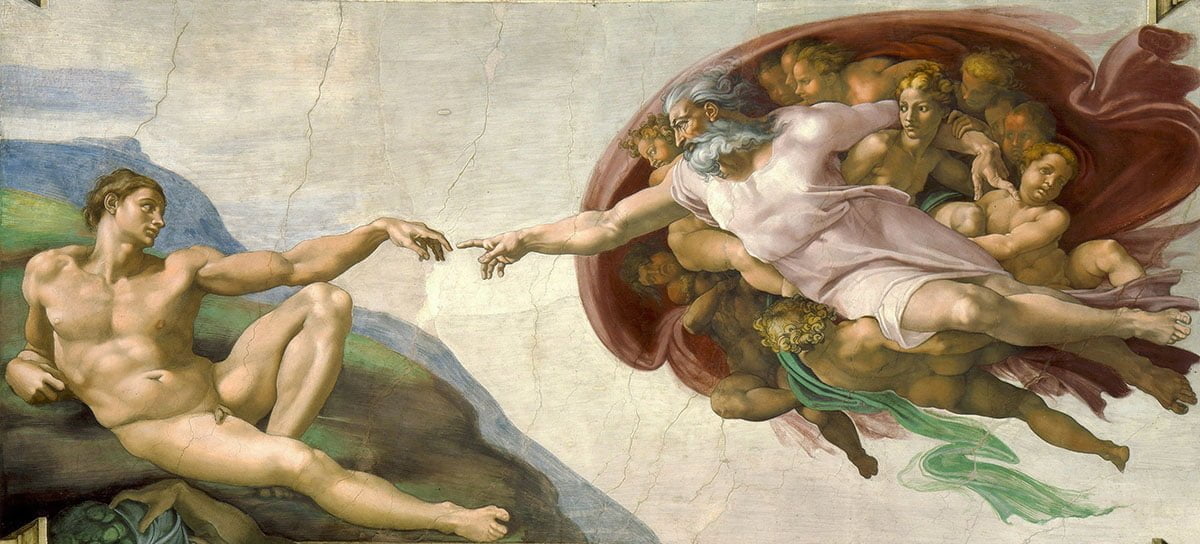

In the towns the bourgeoisie established for themselves a system of trade and business that could exist independently of the Church and Crown. And with the rise of the bourgeoisie there came a huge advancement of the arts. No longer was art purely designed to display the majesty of God. Now art was a way of displaying one’s position in this world. For the bourgeoisie of the Italian Renaissance, art was directly linked to intellectual knowledge of the classical past, the beauties of nature, and the importance of the individual in the world. We see this in various works such as Michelangelo’s David, Botticelli’s Primavera, the portraits of Raphael and Titian etc.

Amongst this new breed of intellectual artist, probably the greatest was Leonardo da Vinci, a man who sought not glory and fame, but rather an understanding of the material world and its intricacies. Perhaps Leonardo’s greatest contributions to art were his scientific drawings. Here we see an artist who really saw a value in his work. These drawings were not made for money, and were never made to be seen by anybody apart from Leonardo, and yet they possess something which is fundamentally understandable to all humans: a need to observe and understand the essence of life.

The most striking example of this is his anatomical drawing showing a foetus in the womb. To call this a purely observational and scientific work is to misunderstand what Leonardo wanted to capture in his study: the fundamental beginnings of all human beings, the state in which mankind exists before it enters the world; something every human being has to go through.

When we are told by bourgeois collectors and critics that art is something beyond everyday human life, in a realm of ideals of beauty, they ought to be reminded that Leonardo, one of the greatest artists of all time, never sought to reflect anything but the most fundamental human life in his works. Even in religious works Leonardo offers us humanity first and foremost. In the Virgin of the Rocks we see a mother looking after children. In the Last Supper we see a group of individuals eat a humble meal.

The Golden Age

Since Leonardo, this need to observe and understand the beauty of humankind has been carried on by artists with completely different professional careers. The Dutch Golden Age (roughly the entire 17th century) was a period of economic boom following the successful revolt of the Dutch against their Spanish rulers in the late 16th century. The Dutch Republic was intensely Protestant and its bourgeoisie were proud of the material success that their monopolised trade with Japan and other countries of the Far East secured them.

In Golden Age Holland, people of all different social standing were buying art of different varieties. The poorer folk could buy etchings or cheap paintings showing ‘genre scenes’, which usually depicted comic depictions of quack doctors, drunkards, prostitutes etc. as well as still life paintings, which displayed all the fundamental material requirements for the good life. This was art that could be understood by anyone, and the Dutch people took pride in being able to own individual works of art.

The more wealthy class could have their portraits painted, reflecting their belief in their own self-worth. Among the portrait painters of Amsterdam was Rembrandt van Rijn, a man who revolutionised the way we see each other. Rembrandt painted in a style of thick impasto and dirty colours, determined to capture the essence of his subjects rather than painting an exact likeness. Amongst his most intimate and touching works are those he made of the women and children he knew. The portrait of his son Titus is a great example of this.

Here we see a boy stare directly into the eyes of his father. As a portrait, it is miles away from the flamboyant and over-complimentary style of Rembrandt’s contemporaries like Rubens and Van Dyke. Rather than create an image of an ideal, Rembrandt has sought to show us directly the connection he feels to another human being. It is not only in pictures of people he loves that Rembrandt does this, in almost all his portraits, commissioned or not, Rembrandt attempts to show us the humanity of his subjects.

Vermeer and the Old Masters

The Dutch Golden age spawned one other outstanding artist, Jan Vermeer. Vermeer lived a humble life in the town of Delft, painting small pictures for little money. Cheap though these painting were, their intense beauty and quality as works of art make them outstanding to the eyes of a modern viewer. Long before photographers became obsessed with capturing ‘everyday life’, Vermeer was painting quiet scenes of the Dutch middle class.

Vermeer’s work is notable in that unlike contemporaries like Jan Steen, he does not attempt to present the people he depicts in a humorous way, but attempts instead to show them in their apparently most dull and uninteresting moments. He paints a lady reading a letter or a child playing on the street with as much intense care as any other artist would paint a mythological scene.

For Vermeer at his most profoundly beautiful and touching we should look at the small painting known as The Milkmaid. Here we have a women at work, doing something she must have to do every day. Seeing something like this in real life we would be forgiven for being uninterested or bored. And yet this painting is anything but boring. It shows directly the beauty of everyday life most people will miss if they do not pay attention.

Here Vermeer seems to be calling for us to appreciate the little things that go on every day. It is miles away from what a working class person might understandably think of the art of the Old Masters. Who could fail to see why Vermeer has felt the need to use Lapis Lazuli, an expensive blue pigment, to create the stunningly beautiful apron around her waist? The bourgeois historian may (wrongly) point out that these works reflect humanity only due to Dutch Protestant materialism (Vermeer converted to Catholicism). In reply to this we should examine some of the Catholic art of this period and see if we find anything different.

Caravaggio and the Church

The painter Caravaggio worked mainly for the Catholic Church in Rome during the Counter-Reformation. While his works are undoubtedly religious, they are above all, to the modern eye, intensely humanist. Unlike his contemporaries, Caravaggio did not paint in the highly ornamental, decorative Baroque manner; full of absurd amounts of floating virgins and puffy cherubs. Caravaggio painted everyday reality; the people he saw on the streets of Rome – prostitutes, beggars, criminals – and the religious aspects of his works are always linked to the poverty and deprivation Caravaggio saw all around him.

Caravaggio was not a slave to the power of the Church. Many of the works he produced were rejected by those who commissioned them because of his insistence on using real life models for his religious figures, particularly his use of famous Roman prostitutes as models for his Madonnas. Many bourgeois art historians have depicted Caravaggio as a straight foreword thug (he famously killed a man in a duel). Yet what they forget is that Caravaggio lived in a time of extreme poverty and crime, from which he could not escape. He saw the world around him was full of horrors, and yet he was able to look through these horrors and see the humanity that connects us all.

Take for example his altarpiece The Seven Acts of Mercy. Here we have a religious work, based upon a Christian ideal of mercy. Yet where is the work of God? Where is the authority of the church? The angels and the Madonna and child do not appear any less human than the rest of the figures. On the right we see a woman feeding an old prisoner with milk from her breast, on the left a man taking off his cloak to give to a naked beggar. What could be more human than an image like this? Here Caravaggio reflects how our worst moments we can still rely on our fellow man to help.

A reflection of humanity

The humanity reflected in these artworks is not something strange to be studied academically. It is a humanity that still connects people today and should therefore be understood as such. Socialism is, before anything else, a way of re-connecting mankind and eliminating the hatred and exploitation brought on by capitalism. In the development of human existence, the bringing of people together in overthrowing their oppressors is of infinite value.

Marxists have absolute confidence in the working class. Art has the power to influence people, and so it should not be seen as a useless luxury reserved for those who have too much time and money. Art reflects better than anything else the beauty of human existence. Art is not necessary in the way food and shelter are, but rather it is there to offer us consolation and give us reason to live, and this is something we all need. Without some means of understanding life artistically, we would be left with a hollow kind of existence.

Art is at once a reflection and a driving force for life. Under socialism, the alienation of working people from art and culture will be destroyed and art can finally take the place in society it should have.