Introductory Note: The following letter by Leon Trotsky appeared in one of the early issues of Partisan Review in 1938 under the editorship of Dwight MacDonald. Trotsky’s hope that this magazine would “take its place in the victorious army of socialism” was not borne out by its subsequent evolution, as his second letter indicates. The disillusioned intellectuals on Partisan Review proceeded from “re-evaluations” of Marxism and rejections of Bolshevism to a sterile preoccupation with problems of pure aesthetics and literary techniques detached from their social roots along with an adaptation to the standpoint of liberal supporters of imperialist policies. In the process MacDonald separated himself from his associate editors and launched a new magazine Politics which, after wallowing helplessly in political, cultural and aesthetic disorientation, recently folded up. Diego Rivera later made his peace with Stalinism, a step which improved neither his art nor his politics. Despite the reconversion of these intellectuals to capitalism and Stalinism, Trotsky’s remarks on the relations of art and politics retain their validity and urgency. More than ever today “the function of art is determined by its relation to the revolution.”

You have been kind enough to invite me to express my views on the state of present-day arts and letters. I do this not without some hesitation. Since my book Literature and Revolution (1923), I have not once returned to the problem of artistic creation and only occasionally have I been able to follow the latest developments in this sphere. I am far from pretending to offer an exhaustive reply. The task of this letter is to correctly pose the question.

Generally speaking, art is an expression of man’s need for a harmonious and complete life, that is to say, his need for those major benefits of which a society of classes has deprived him. That is why a protest against reality, either conscious or unconscious, active or passive, optimistic or pessimistic, always forms part of a really creative piece of work. Every new tendency in art has begun with rebellion. Bourgeois society showed its strength throughout long periods of history in the fact that, combining repression, and encouragement, boycott and flattery, it was able to control and assimilate every “rebel” movement in art and raise it to the level of official “recognition.” But each time this “recognition” betokened, when all is said and done, the approach of trouble. It was then that from the left wing of the academic school or below it – i.e. from the ranks of new generation of bohemian artists – a fresher revolt would surge up to attain in its turn, after a decent interval, the steps of the academy. Through these stages passed classicism, romanticism, realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism, cubism, futurism… Nevertheless, the union of art and the bourgeoisie remained stable, even if not happy, only so long as the bourgeoisie itself took the initiative and was capable of maintaining a regime both politically and morally “democratic.” This was a question of not only giving free rein to artists and playing up to them in every possible way, but also of granting special privileges to the top layer of the working class, and of mastering and subduing the bureaucracy of the unions and workers’ parties. All these phenomena exist in the same historical plane.

Decay of Capitalist Society

The decline of bourgeois society means an intolerable exacerbation of social contradictions, which are transformed inevitably into personal contradictions, calling forth an ever more burning need for a liberating art. Furthermore, a declining capitalism already finds itself completely incapable of offering the minimum conditions for the development of tendencies in art which correspond, however little, to our epoch. It fears superstitiously every new word, for it is no longer a matter of corrections and reforms for capitalism but of life and death. The oppressed masses live their own life. Bohemianism offers too limited a social base. Hence new tendencies take on a more and more violent character, alternating between hope and despair. The artistic schools of the last few decades – cubism, futurism, dadaism, surrealism – follow each other without reaching a complete development. Art, which is the most complex part of culture, the most sensitive and at the same time the least protected, suffers most from the decline and decay of bourgeois society.

To find a solution to this impasse through art itself is impossible. It is a crisis which concerns all culture, beginning at its economic base and ending in the highest spheres of ideology. Art can neither escape the crisis nor partition itself off. Art cannot save itself. It will rot away inevitably – as Grecian art rotted beneath the ruins of a culture founded on slavery – unless present-day society is able to rebuild itself. This task is essentially revolutionary in character. For these reasons the function of art in our epoch is determined by its relation to the revolution.

But precisely in this path history has set a formidable snare for the artist. A whole generation of “leftist” intelligentsia has turned its eyes for the last ten or fifteen years to the East and has bound its lot, in varying degrees, to a victorious revolution, if not to a revolutionary proletariat. Now, this is by no means one and the same thing. In the victorious revolution there is not only the revolution, but there is also the new privileged class which raises itself on the shoulders of the revolution. In reality, the “leftist” intelligentsia has tried to change masters. What has it gained?

The October revolution gave a magnificent impetus to all types of Soviet art. The bureaucratic reaction, on the contrary, has stifled artistic creation with a totalitarian hand. Nothing surprising here! Art is basically a function of the nerves and demands complete sincerity. Even the art of the court of absolute monarchies was based on idealization but not on falsification. The official art of the Soviet Union – and there is no other over there – resembles totalitarian justice, that is to say, it is based on lies and deceit. The goal of justice, as of art, is to exalt the “leader,” to fabricate a heroic myth. Human history has never seen anything to equal this in scope and impudence. A few examples will not be superfluous.

The well-known Soviet writer, Vsevolod Ivanov, recently broke his silence to proclaim eagerly his solidarity with the justice of Vyshinsky. The general extermination of the old Bolsheviks, “those putrid emanations of capitalism,” stimulates in the artists a “creative hatred” in Ivanov’s words. Romantic, cautious by nature, lyrical, none too outspoken, Ivanov recalls Gorki, in many ways, but in miniature. Not a prostitute by nature, he preferred to remain quiet as long as possible but the time came when silence meant civil and perhaps physical annihilation. It is not a “creative hatred” that guides the pen of these writers but paralysing fear.

Alexis Tolstoy, who has finally permitted the courtesan to master the artist, has written a novel expressly to glorify the military exploits of Stalin and Voroshilov at Tsaritsin. In reality, as impartial documents bear witness, the army of Tsaritsin – one of the two dozen armies of the revolution – played a rather sorry role. The two “heroes” were relieved of their posts.[1] If the honest and simple Chapayev, one of the real heroes of the civil war is glorified in a Soviet film, it is only because he did not live until the “epoch of Stalin” which would have shot him as a Fascist agent. The same Alexis Tolstoy is now writing a drama on the theme of the year 1919: “The Campaign of the Fourteen Powers.” The principal heroes of this piece, according to the words of the author, are Lenin, Stalin and Voroshilov. Their images [of Stalin and Voroshilov!] haloed in glory and heroism, will pervade the whole drama. Thus, a talented writer who bears the name of the greatest and most truthful Russian realist, has become a manufacturer of “myths” to order!

Very recently, the 27th of April of this year, the official government paper Izvestia, printed a reproduction of a new painting representing Stalin as the organizer of the Tiflis strike in March 1902. However, it appears from documents long known to the public, that Stalin was in prison at that time and besides not in Tiflis but in Batum. This time the lie was too glaring! Izvestia was forced to excuse itself the next day for its deplorable blunder. No one knows what happened to the unfortunate picture, which was paid for from State funds.

Dozens, hundreds, thousands of books, films, canvases, sculptures immortalize and glorify such historic “episodes.” Thus the numerous pictures devoted to the October revolution do not fail to represent a revolutionary “Centre,” with Stalin at its head, which never existed. It is necessary to say a few words concerning the gradual preparation of this falsification. Leonid Serebriakov, shot after the Piatakov-Radek trial, drew my attention in 1924 to the publication in Pravda, without explanation, of extracts from the minutes of the Central Committee of the latter part of 1917. An old secretary of the Central Committee, Serebriakov had numerous contacts behind the scenes with the party apparatus, and he knew enough the object of this unexpected publication: it was the first step, still a cautious one, towards the principal Stalinist myth, which now occupies so great a place in Soviet art.

The Mythical “Centre”

From an historical distance the October insurrection seem much more planned and monolithic than what it proved to be in reality. In fact, there were lacking neither vacillations, search for solutions, nor impulsive beginnings which led nowhere. Thus, at the meeting of the Central Committee on the 16th of October, improvised in one night, in the absence of the most active leaders of the Petrograd Soviets, it was decided to round out the general staff of the insurrection with an auxiliary “Centre” created by the party and composed of Sverdlov, Stalin, Bubnov, Uritzky and Djerjinsky. At the very same time at the meeting of the Petrograd Soviet, a Revolutionary Military Committee was formed which from the moment of its appearance did so much work towards the preparation of the insurrection that the “Centre,” appointed the night before, was forgotten by everybody, even by its own members. There were more than a few of such improvisations in the whirlwind of this period.[2] Stalin never belonged to the Military Revolutionary Committee, did not appear at Smolny, staff headquarters of the revolution, had nothing to do with the practical preparation of the insurrection, but was to be found editing Pravda and writing drab articles, which were very little read. During the following years nobody once mentioned the “Practical Centre.” In memoirs of participants in the insurrection – and there is no shortage of these – the name of Stalin is not once mentioned. Stalin himself, in an article on the anniversary of the October insurrection, in the Pravda of November 7, 1918, describing all the groups and individuals who took part in the insurrection, does not say a word about the “Practical Centre.” Nevertheless, the old minutes, discovered by chance in 1924 and falsely interpreted, have served as a base for the bureaucratic legend. In every compilation, bibliographical guide, even in recently edited schoolbooks, the revolutionary “Centre” has a prominent place with Stalin, at its head. Furthermore, no one has tried, not even out of a sense of decency, to explain where and how this “Centre” established its headquarters, to whom it gave orders and what they were, and whether minutes were taken where they are. We have here all the features of the Moscow trials.

With the docility which distinguishes it, Soviet art so-called, has made this bureaucratic myth into one of its favourite subjects for artistic creation. Sverdlov, Djerjinsky, Uritsky and Bubnov are represented in oils or in tempera, seated or standing around Stalin and following his words with rapt attention. The building where the “Centre” has its headquarters is intentionally depicted in a vague fashion, in order to avoid the embarrassing question of the address. What can one hope for or demand of artists who are forced to follow with their brushes the crude lines of what they themselves realize is an historical falsification?

The style of present-day official Soviet painting is called “socialist realism.” The name itself has evidently been invented by some high functionary in the department of the arts. This “realism” consists in the imitation of provincial daguerreotypes of the third quarter of the last century; the “socialist” character apparently consists in representing, in the manner of pretentious photography, events which never took place. It is impossible to read Soviet verse and prose without physical disgust, mixed with horror, or to look at reproductions of paintings and sculpture in which functionaries armed with pens, brushes, and scissors, under the supervision of functionaries armed with Mausers, glorify the “great” and “brilliant” leaders, actually devoid of the least spark of genius or greatness. The art of the Stalinist period will remain as the frankest expression of the profound decline of the proletarian revolution.

This state of things is not confined, however, within the frontiers of the U.S.S.R. Under the guise of a belated recognition of the October revolution, the “left” wing of the western intelligentsia has fallen on its knees before the Soviet bureaucracy. As a rule, those artists with some character and talent have kept aloof. But the appearance in the first ranks, of the failures, careerists and nobodies is all the more unfortunate. A rash of Centres and Committees of all sorts has broken out, of secretaries of both sexes, inevitable letters from Romain Rolland, subsidized editions, banquets and congresses, in which it is difficult to trace the line of demarcation between art and the G.P.U. Despite this vast spread of activity, this militarised movement has not produced one single work that was able to outlive its author or its inspirers of the Kremlin.

Rivera and October

In the field of painting, the October revolution has found her greatest interpreter not in the U.S.S.R. but in faraway Mexico, not among the official “friends,” but in the person of a so-called “enemy of the people” whom the Fourth International is proud to number in its ranks. Nurtured in the artistic cultures of all peoples, all epochs, Diego Rivera has remained Mexican in the most profound fibres of his genius. But that which inspired him in these magnificent frescoes, which lifted him up above the artistic tradition, above contemporary art in a certain sense, above himself, is the mighty blast of the proletarian revolution. Without October, his power of creative penetration into the epic of work, oppression and insurrection, would never have attained such breadth and profundity. Do you wish to see with your own eyes the hidden springs of the social revolution? Look at the frescoes of Rivera. Do you wish to know what revolutionary art is like? Look at the frescoes of Rivera.

Come a little closer and you will see clearly enough, gashes and spots made by vandals: Catholics and other reactionaries, including, of course, Stalinists. These cuts and gashes give even greater life to the frescoes. You have before you, not simply a “painting,” an object of passive aesthetic contemplation, but a living part of the class struggle. And it is at the same time a masterpiece!

Only the historical youth of a country which has not yet emerged from the stage of struggle for national independence, has allowed Rivera’s revolutionary brush to be used on the walls of the public buildings of Mexico. In the United States it was more difficult. Just as the monks in the Middle Ages, through ignorance, it is true, erased antique literary productions from parchments to cover them with their scholastic ravings, just so Rockefeller’s lackeys, but this time maliciously, covered the frescoes of the talented Mexican with their decorative banalities. This recent palimpsest will conclusively show future generations the fate of art degraded in a decaying bourgeois society.

The situation is no better, however, in the country of the October revolution. Incredible as it seemed at first sight, there was no place for the art of Diego Rivera, either in Moscow, or in Leningrad, or in any other section of the U.S.S.R. where the bureaucracy born of the revolution was erecting grandiose palaces and monuments to itself. And how could the Kremlin clique tolerate in its kingdom an artist who paints neither icons representing the “leader” nor life-size portraits of Voroshilov’s horse? The closing of the Soviet doors to Rivera will brand forever with an ineffaceable shame the totalitarian dictatorship.

Will it go on much longer – this stifling, this trampling under foot and muddying of everything on which the future of humanity depends? Reliable indications say no. The shameful and pitiable collapse of the cowardly and reactionary politics of the Popular Fronts in Spain and France, on the one hand, and the judicial frame-ups of Moscow, on the other, portend the approach of a major turning point not only in the political sphere, but also in the broader sphere of revolutionary ideology. Even the unfortunate “friends” – but evidently not the intellectual and moral shallows of The New Republic and Nation – are beginning to tire of the yoke and whip. Art, culture, politics need a new perspective. Without it humanity will not develop. But never before has the prospect been as menacing and catastrophic as now. That is the reason why panic is the dominant state of mind of the bewildered intelligentsia. Those who oppose an irresponsible scepticism to the yoke of Moscow do not weigh heavy in the balance of history. Scepticism is only another form, and not the best, of demoralization. Behind the act, so popular now, of impartially keeping aloof from the Stalinist bureaucracy as well as its revolutionary adversaries, is hidden nine times out of ten a wretched prostration before the difficulties and dangers of history. Nevertheless, verbal subterfuges and petty manoeuvres will be of no use. No one will be granted either pardon or respite. In the face of the era of wars and revolutions which is drawing near, everyone will have to give an answer: philosophers, poets, painters as well as simple mortals.

In the June issue of your magazine I found a curious letter from an editor of a Chicago magazine, unknown to me. Expressing (by mistake, I hope) his sympathy for your publication, he writes: “I can see no hope however [?] from the Trotskyites or other anaemic splinters which have no mass base.” These arrogant words tell more about the author than he perhaps wanted to say. They show above all that the laws of development of society have remained a seven times sealed book for him. Not a single progressive idea has begun with a “mass base,” otherwise it would not have been a progressive idea. It is only in its last stage that the idea finds its masses – if, of course, it answers the needs of progress. All great movements have begun as “splinters” of older movements. In the beginning, Christianity was only a “splinter” of Judaism; Protestantism a “splinter” of Catholicism, that is to say decayed Christianity. The group of Marx and Engels came into existence as a “splinter” of the Hegelian Left. The Communist International germinated during the war from the “splinters” of the Social Democratic International. If these pioneers found themselves able to create a mass base, it was precisely because they did not fear isolation. They knew beforehand that the quality of their ideas would be transformed into quantity. These “splinters” did not suffer from anaemia; on the contrary, they carried within themselves the germs of the great historical movements of tomorrow.

“Splinters” and Pioneers

In very much the same way, to repeat, a progressive movement occurs in art. When an artistic tendency has exhausted its creative resources, creative “splinters” separate from it, which are able to look at the world with new eyes. The more daring the pioneers show in their ideas and actions, the more bitterly they oppose themselves to established authority which rests on a conservative “mass base,” the more conventional souls, sceptics, and snobs are inclined to see in the pioneers, impotent eccentrics or “anaemic splinters‚” But in the last analysis it is the conventional souls, sceptics and snobs who are wrong – and life passes them by.

The Thermidorian bureaucracy, to whom one cannot deny either a certain animal sense of danger or a strong instinct of self-preservation, is not at all inclined to estimate its revolutionary adversaries with such whole-hearted disdain, a disdain which is often coupled with lightness and inconsistency. In the Moscow trials, Stalin, who is not a venturesome player by nature, staked on the struggle against “Trotskyism,” the fate of the Kremlin oligarchy as well as his own personal destiny. How can one explain this fact? The furious international campaign against “Trotskyism,” for which a parallel in history will be difficult to find, would be absolutely inexplicable if the “splinters” were not endowed with an enormous vitality. He who does not see this today will see it better tomorrow.

As if to complete his self-portrait with one brilliant stroke, your Chicago correspondent vows – what bravery! – to meet you in a future concentration camp either fascist or “communist.” A fine program! To tremble at the thought of a concentration camp is certainly not admirable. But is it much better to foredoom oneself and one’s ideas to this grim hospitality? With the Bolshevik “amoralism” which is characteristic of us, we are ready to suggest that gentlemen – by no means anaemic – who capitulate before the fight and without a fight really deserve nothing better than the concentration camp.

It would be a different matter if your correspondent simply said: in the sphere of literature and art we wish no supervision on the part of “Trotskyists” any more than from the Stalinists. This protest would be, in essence, absolutely just. One can only retort that to aim it at those who are termed “Trotskyists” would be to batter in an open door. The ideological base of the conflict between the Fourth and Third Internationals is the profound disagreement not only on the tasks of the party but in general on the entire material and spiritual life of mankind.

The real crisis of civilization is above all the crisis of revolutionary leadership. Stalinism is the greatest element of reaction in this crisis. Without a new flag and a new program it is impossible to create a revolutionary mass base; consequently it is impossible to rescue society from its dilemma. But a truly revolutionary party is neither able nor willing to take upon itself the task of “leading” and even less of commanding art, either before or after the conquest of power. Such a pretension could only enter the head of a bureaucracy – ignorant and impudent, intoxicated with its totalitarian power – which has become the antithesis of the proletarian revolution. Art, like science, not only does not seek orders, but by its very essence, cannot tolerate them. Artistic creation has its laws – even when it consciously serves a social movement. Truly intellectual creation is incompatible with lies, hypocrisy and the spirit of conformity. Art can become a strong ally of revolution only in so far as it remains faithful to itself. Poets, painters, sculptors and musicians will themselves find their own approach and methods, if the struggle for freedom of oppressed classes and peoples scatters the clouds of scepticism and of pessimism which cover the horizon of mankind. The first condition of this regeneration is the overthrow of the domination of the Kremlin bureaucracy.

May your magazine take its place in the victorious army of socialism and not in a concentration camp!

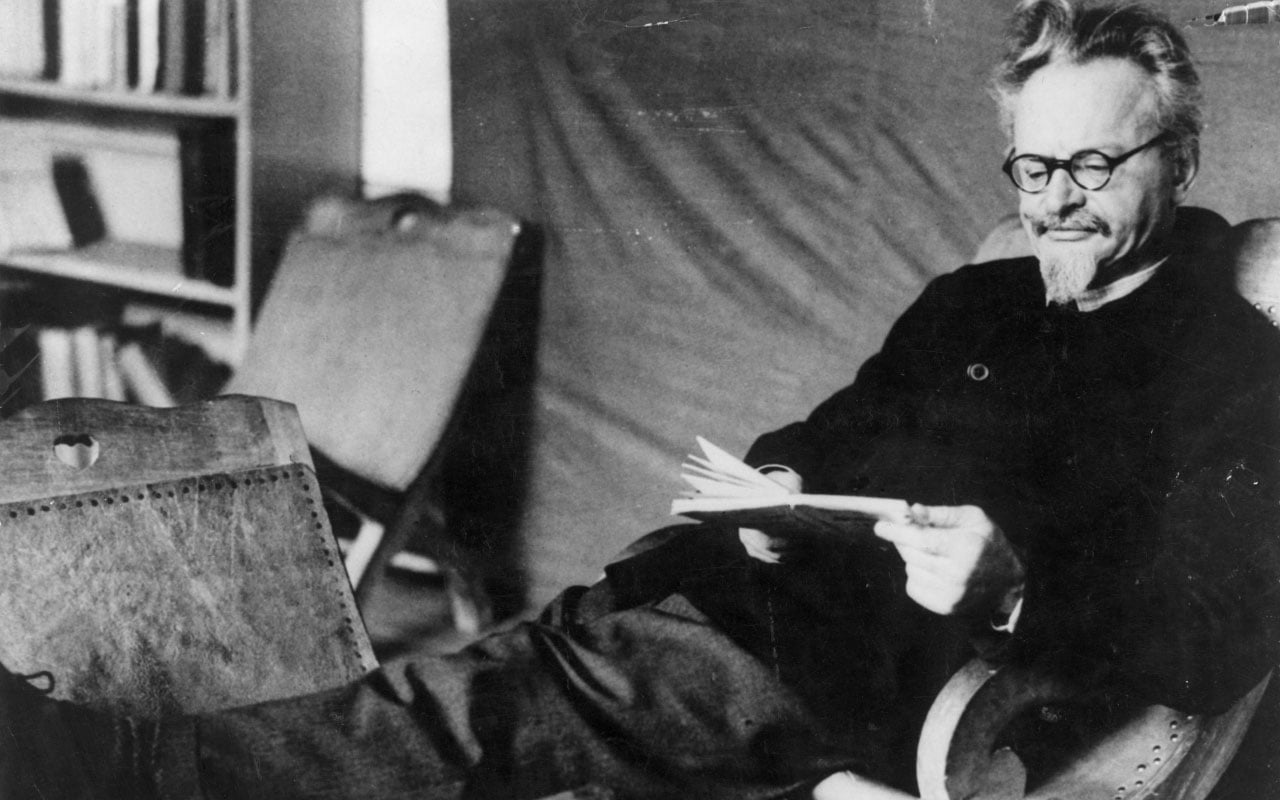

Leon Trotsky,

Coyoacan, D. F., June 18, 1938

(First Published: Fourth International March-April 1950, Volume 11 No. 2 page 61-64. Copyleft: This text was taken from the Leon Trotsky Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1938/1938-lit.htm. Permission is granted to copy and/or distribute this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License)

A Second Letter

(The following letter was addressed to Dwight MacDonald, then editor of Partisan Review on January 29, 1938.)

Dear Mr. MacDonald:

I shall speak with you very frankly inasmuch as reservations or insincere half-praises would signify a lack of respect for you and our undertaking.

It is my general impression that the editors of Partisan Review are capable, educated and intelligent people but they have nothing to say. They seek themes which are incapable of hurting anyone but which likewise are incapable of giving anybody anything. I have never seen or heard of a group with such a mood gaining success, i.e., winning influence and leaving some sort of trace in the history of thought.

Note that I am not at all touching upon the content of your ideas (perhaps because I cannot discern them in your magazine). “Independence” and “freedom” are two empty notions. But I am ready to grant that “independence” and “freedom” as you understand them represent some kind of actual cultural value. Excellent! But then it is necessary to defend them with sword, or at least with whip, in hand. Every new artistic or literary tendency (naturalism, symbolism, futurism, cubism, expressionism and so forth and so on) has begun with a “scandal,” breaking the old respected crockery, bruising many established authorities. This flowed not at all solely from publicity seeking (although there was no lack of this). No, these people – artists, as well as literary critics – had something to say. They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist.

So far as your publication is concerned, it wishes, in the main instance, apparently to demonstrate its respectability. You defend yourselves from the Stalinists like well-behaved young ladies whom street rowdies insult. “Why are we attacked?” you complain “we want only one thing: to live and let others live.” Such a policy cannot gain success.

Of course, there are not a few disappointed “friends of the USSR” and generally dismal intellectuals who, having been burned once, fear more than anything else to become again engaged. These people will send you tepid, sympathetic letters but they will not guarantee the success of the magazine since serious success has never yet been based on political, cultural and aesthetic disorientation.

I wanted to hope that this was but a temporary condition and that the publishers of Partisan Review would cease to be afraid of themselves. I must say, however, that the Symposium outlined by you is not at all capable of strengthening these hopes. You phrase the question about Marxism as if you were beginning history from a clean page. The very Symposium title itself sounds extremely pretentious and at the same time confused. The majority of the writers whom you have invited have shown by their whole past – alas! – a complete incapacity for theoretical thinking. Some of them are political corpses. How can a corpse be entrusted with deciding whether Marxism is a living force? No, I categorically refuse to participate in that kind of endeavour.

A world war is approaching. The inner political struggle in all countries tends to become transformed into civil war. Currents of the highest tension are active in all fields of culture and ideology. You evidently wish to create a small cultural monastery, guarding itself from the outside world by scepticism, agnosticism and respectability. Such an endeavour does not open up any kind of perspective.

It is entirely possible that the tone of this letter will appear to you as sharp, impermissible, and “sectarian.” In my eyes this would constitute merely supplementary proof of the fact that you wish to publish a peaceful “little” magazine without participating actively in the cultural life of your epoch. If, on the contrary, you do not consider my “sectarian” tone a hindrance to a future exchange of opinion then I remain fully at your service.

Sincerely,

Leon Trotsky, January 29, 1939

Notes

[1] See, for example, the article of N. Markin, “Voroshilov and the Red Army” in Leon Trotsky’s The Stalin School of Falsification.

[2] This question is fully developed in History of the Russian Revolution in the chapter entitled “Legends of the Bureaucracy.”