Only a few short years ago it seemed that the tech market could do no wrong. Whatever problems the rest of world capitalism faced, the tech industries looked to be moving from success to success, with ever-larger profits each year. But, as Steve Jones (not Jobs) reports, the major technology firms – such as Apple – are now facing an increasingly uncertain future.

Only a few short years ago it seemed that the tech market could do no wrong. Whatever problems the rest of world capitalism faced, the tech industries looked to be moving from success to success, with ever-larger profits each year. Every new product was greeted by queues of enthusiasts lining up at midnight to be first to buy the new device, even if it was almost identical to the old one they already had.

The fact that most new devices now seem very similar to older models or competitors products, however, is an indication of some of the problems facing the industry. Where once Apple ruled the world, various other firms are now able to provide seemingly decent substitutes for a lower price. The Android operating software – which covers both phones and tablets – seems to have founds its feet after several false starts and abandoned alternatives to Apple’s iOS. The same applies to the Google software now widely used.

In fact, the world is now awash with mobile phones, laptops, tablets, etc. So much so that there are not enough people on the planet to buy all this produce, even if they could afford it. The tech industry is now facing a classic crisis of overproduction, as Marx would have explained it long ago. Even businesses like Twitter are not immune, with the company announcing a 9% cut in its workforce following a slowdown in profit growth.

You would think therefore that Apple – along with other competitors like Sony and newer entries into the field like Huawei (let alone Microsoft, of course) – would have been privately ecstatic over the Samsung exploding Galaxy Note 7 fiasco. Samsung – one of the big players in the tech world – have had to withdraw the high-profile phone and are now facing an expected 30% fall in profits. It is hard to feel any sympathy for them, however, given they knew long ago about the problem with the lithium batteries but for months chose not to seriously try and fix it. So why the gloom now surrounding Apple and the rest?

The gadget glut

One factor is that the battery problem goes beyond Samsung and the doomed Galaxy model. Modern portable technology requires smaller but far more powerful batteries to operate devices, all of which are extremely energy-hungry. The lithium battery provides this, but, at the small size now required by manufacturers, has stability problems – that is, they can swell up, overheat and then catch fire. Any production flaw in a battery may cause them to become dangerous over time. Laptop batteries have been problematic for several years now, and experts warn against leaving them attached to chargers for long periods. There is also a problem that batteries left with no charge for a long period, of weeks or months, may stop working full stop or become erratic.

The wider problem is to do with the sheer glut of devices and the fact that there is a limit as to how far forward you can take these based on current technology. The classic case study is Apple itself, the market leader for the whole of the 21st century so far. Anyone who had shares in Apple seemed to posses a gateway to endless profits. However, Apple has now reported a 4% fall in quarterly revenue, the third such fall in a row, representing the first annual fall in profits for 15 years. Even worse, Apple’s profit figures for China have fallen by a fifth. China and Korea are where most of the world’s tech production is sited.

For years Apple seemed to have the knack of producing ever more popular items, pulling an endless stream of rabbits out of the hat. The MacBook came out in 2006; the iPod in 2001; the iPhone in 2007; and the iPad in 2010. Each of these effectively created a completely new market.

Apple: Hoist by its own petard

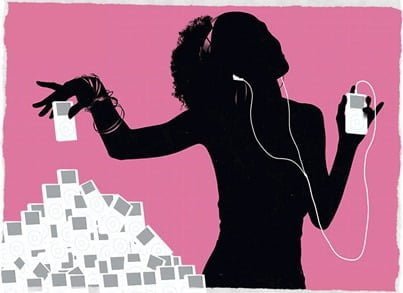

The iPod is a useful case study to look at. Before the iPod was introduced, the music industry was still largely hostile to the download market. They could see how BitTorrent software and the peer-to-peer sharing were creating a huge resource of free but illegal music, encoded into mp3 files using freely available software – files that were being shared around online by millions of people. But they had no idea what to do about this.

The iPod is a useful case study to look at. Before the iPod was introduced, the music industry was still largely hostile to the download market. They could see how BitTorrent software and the peer-to-peer sharing were creating a huge resource of free but illegal music, encoded into mp3 files using freely available software – files that were being shared around online by millions of people. But they had no idea what to do about this.

As the internet got faster, so the problem got bigger. They tried suing individual downloaders, creating a public relations nightmare in the process. They tried restricting what could be officially and legally downloaded, forcing firms selling these downloads to have restrictive Digital Rights Management (DRM) encoded into the files. All of this merely pushed people back to the “grey area” free downloads and file-sharing operations.

Apple came along and said they were having none of this. Using the integrated iTunes software, they set up a synchronised easy-to-use operation, whereby people could easily download and start playing music on a sleek portable iPod with just a few clicks and no DRM to boot. They could rip their cds using iTunes and even burn discs to create new cds using downloaded files. The iTunes software also accepted imported mp3 files obtained from “other” sources. Given the size of the market Apple had created, the music industry quickly stopped holding back on what was available and embraced the new market, despite their concerns over the lower profits from digital downloads compared to physical media.

A similar “ease-of-use” experience would be presented for other devices, such as the iPad and the iPhone, both of which were market leaders. However, the seeds of Apple’s problems were planted here. The iPhone – as it has become more and more powerful as a device – has killed off the iPod since the phone now does the same job.

Streaming

In addition, with faster internet connections and the introduction of services such as Spotify, the music industry has gravitated towards streaming as the new option of choice to replace downloads. Streaming has the advantage that you never actually own the music and has much lower royalty payments attached to them compared to downloads. So low, in fact, that many artists now earn most of their income from gigs and merchandising, etc.

YouTube has also become a main source of music for many people. Although initially hostile to YouTube, the music industry has come to see it as a useful tool for promotion. The big music labels were also bought off. When Google were about to buy YouTube, all the major record companies were given free equity stock in the company. After the sale went through, the new owners offered to buy back the equity, giving the companies a nice income which – as it was classified as investment profits – did not have to be shared out with the artists who were now seeing a further fall in royalties.

Apple has introduced a music streaming service also – called, with stunning originality, Apple Music – but has to compete with already existing operations like Spotify, Deezer or Tidal, nearly all of which have a free-option service. Amazon has also snuck in with their own service, linked to Amazon Prime, and the new voice-controlled Echo speakers. Although none of the streaming services seem to be making any great profits yet, this has left Apple and iTunes in something of a pickle.

Storm clouds

Suddenly iTunes no longer rules the roost. The other Apple devices are facing competition from cheaper options and Apple seems to have hit a technology dead-end. The new iPhone is pretty much the same as the old one, apart from the inconvenience of not having a dedicated earphone socket. Apple hope you will buy their own expensive (poor quality) earphones that either use the Apple-unique lighting rod charging socket or are wireless; although the Air Pods, as they are called, have hit a production delay.

Suddenly iTunes no longer rules the roost. The other Apple devices are facing competition from cheaper options and Apple seems to have hit a technology dead-end. The new iPhone is pretty much the same as the old one, apart from the inconvenience of not having a dedicated earphone socket. Apple hope you will buy their own expensive (poor quality) earphones that either use the Apple-unique lighting rod charging socket or are wireless; although the Air Pods, as they are called, have hit a production delay.

The trick of “forced obsolesce” is also popping up with other Apple devices. The new range of MacBooks, being announced as part of a big “hello again” presentation of “new stuff” on 27th October, not only remove the cheapest 11-inch MacBook Air option from the market, but also only have USB-C sockets, taking away the old standard USB-A sockets. The SD-card sockets are also gone, although we do get a touch-screen “magic toolbar” bar at the top of the keyboard, replacing the F-keys, and a fingerprint scanner button has been sighted in leaked pics. New Skylake processors and/or mobile Xeon E3 chips may be introduced which could force up costs – a problem with Apple computers already compared to the opposition.

In truth, many industry observers are now detecting a slowdown in what actually changes from model to model as each new version comes onto the market. For devices such as the industry-standard MacBook Pro, the new changes will be the first since 2013 and the leaked pics hardly suggest a dramatic change this time around. Operating software upgrades, such as the new iOS 10.1, seem to contain less that is really new or wanted each time. Apple did hope that the iWatch smart watch device, introduced in 2014, might be the next big thing, but the sales of these have not proved as popular as was the case with iPads or iPods when they first came out.

And so the storm clouds are starting to appear in the numbers. Firms like Apple are having to look at their rising research and development costs and have started “revising” production targets. Meanwhile, the warehouse mountains of tech goods are getting larger and larger. Ironically, from being the industry which bucked the trend during the recent crisis, the consumer technology sector may now become its most high-profile example.

Technology and revolution

The huge advances in technology over the last few decades should have provided the basis for rising living standards and a better society. However, for the full potential of technological advances to be realised, we need socialism: a system that could utilise these advances to plan production and distribution for the benefit of all. Instead, we have billions of smartphones, laptops and a plethora of other gadgets, on the one hand; and yet, on the other hand, people are living in poverty, facing basic problems of hunger, sickness, and homelessness on a daily basis.

At the end of the day, you cannot live inside a smartphone or eat it if you are hungry. Capitalism – with private property, competition, and production for profit – has become an enormous barrier to continued development of science and technology. To have a further technological revolution in society, we need a socialist one!

Only a few short years ago it seemed that the tech market could do no wrong. Whatever problems the rest of world capitalism faced, the tech industries looked to be moving from success to success, with ever-larger profits each year. Every new product was greeted by queues of enthusiasts lining up at midnight to be first to buy the new device, even if it was almost identical to the old one they already had.

The fact that most new devices now seem very similar to older models or competitors products, however, is an indication of some of the problems facing the industry. Where once Apple ruled the world, various other firms are now able to provide seemingly decent substitutes for a lower price. The Android operating software – which covers both phones and tablets – seems to have founds its feet after several false starts and abandoned alternatives to Apple’s iOS. The same applies to the Google software now widely used.

In fact, the world is now awash with mobile phones, laptops, tablets, etc. So much so that there are not enough people on the planet to buy all this produce, even if they could afford it. The tech industry is now facing a classic crisis of overproduction, as Marx would have explained it long ago. Even businesses like Twitter are not immune, with the company announcing a 9% cut in its workforce following a slowdown in profit growth.

You would think therefore that Apple – along with other competitors like Sony and newer entries into the field like Huawei (let alone Microsoft, of course) – would have been privately ecstatic over the Samsung exploding Galaxy Note 7 fiasco. Samsung – one of the big players in the tech world – have had to withdraw the high-profile phone and are now facing an expected 30% fall in profits. It is hard to feel any sympathy for them, however, given they knew long ago about the problem with the lithium batteries but for months chose not to seriously try and fix it. So why the gloom now surrounding Apple and the rest?

The gadget glut

One factor is that the battery problem goes beyond Samsung and the doomed Galaxy model. Modern portable technology requires smaller but far more powerful batteries to operate devices, all of which are extremely energy-hungry. The lithium battery provides this, but, at the small size now required by manufacturers, has stability problems – that is, they can swell up, overheat and then catch fire. Any production flaw in a battery may cause them to become dangerous over time. Laptop batteries have been problematic for several years now, and experts warn against leaving them attached to chargers for long periods. There is also a problem that batteries left with no charge for a long period, of weeks or months, may stop working full stop or become erratic.

The wider problem is to do with the sheer glut of devices and the fact that there is a limit as to how far forward you can take these based on current technology. The classic case study is Apple itself, the market leader for the whole of the 21st century so far. Anyone who had shares in Apple seemed to posses a gateway to endless profits. However, Apple has now reported a 4% fall in quarterly revenue, the third such fall in a row, representing the first annual fall in profits for 15 years. Even worse, Apple’s profit figures for China have fallen by a fifth. China and Korea are where most of the world’s tech production is sited.

For years Apple seemed to have the knack of producing ever more popular items, pulling an endless stream of rabbits out of the hat. The MacBook came out in 2006; the iPod in 2001; the iPhone in 2007; and the iPad in 2010. Each of these effectively created a completely new market.

Apple: Hoist by its own petard

The iPod is a useful case study to look at. Before the iPod was introduced, the music industry was still largely hostile to the download market. They could see how BitTorrent software and the peer-to-peer sharing were creating a huge resource of free but illegal music, encoded into mp3 files using freely available software – files that were being shared around online by millions of people. But they had no idea what to do about this.

As the internet got faster, so the problem got bigger. They tried suing individual downloaders, creating a public relations nightmare in the process. They tried restricting what could be officially and legally downloaded, forcing firms selling these downloads to have restrictive Digital Rights Management (DRM) encoded into the files. All of this merely pushed people back to the “grey area” free downloads and file-sharing operations.

Apple came along and said they were having none of this. Using the integrated iTunes software, they set up a synchronised easy-to-use operation, whereby people could easily download and start playing music on a sleek portable iPod with just a few clicks and no DRM to boot. They could rip their cds using iTunes and even burn discs to create new cds using downloaded files. The iTunes software also accepted imported mp3 files obtained from “other” sources. Given the size of the market Apple had created, the music industry quickly stopped holding back on what was available and embraced the new market, despite their concerns over the lower profits from digital downloads compared to physical media.

A similar “ease-of-use” experience would be presented for other devices, such as the iPad and the iPhone, both of which were market leaders. However, the seeds of Apple’s problems were planted here. The iPhone – as it has become more and more powerful as a device – has killed off the iPod since the phone now does the same job.

Streaming

In addition, with faster internet connections and the introduction of services such as Spotify, the music industry has gravitated towards streaming as the new option of choice to replace downloads. Streaming has the advantage that you never actually own the music and has much lower royalty payments attached to them compared to downloads. So low, in fact, that many artists now earn most of their income from gigs and merchandising, etc.

YouTube has also become a main source of music for many people. Although initially hostile to YouTube, the music industry has come to see it as a useful tool for promotion. The big music labels were also bought off. When Google were about to buy YouTube, all the major record companies were given free equity stock in the company. After the sale went through, the new owners offered to buy back the equity, giving the companies a nice income which – as it was classified as investment profits – did not have to be shared out with the artists who were now seeing a further fall in royalties.

Apple has introduced a music streaming service also – called, with stunning originality, Apple Music – but has to compete with already existing operations like Spotify, Deezer or Tidal, nearly all of which have a free-option service. Amazon has also snuck in with their own service, linked to Amazon Prime, and the new voice-controlled Echo speakers. Although none of the streaming services seem to be making any great profits yet, this has left Apple and iTunes in something of a pickle.

Storm clouds

Suddenly iTunes no longer rules the roost. The other Apple devices are facing competition from cheaper options and Apple seems to have hit a technology dead-end. The new iPhone is pretty much the same as the old one, apart from the inconvenience of not having a dedicated earphone socket. Apple hope you will buy their own expensive (poor quality) earphones that either use the Apple-unique lighting rod charging socket or are wireless; although the Air Pods, as they are called, have hit a production delay.

The trick of “forced obsolesce” is also popping up with other Apple devices. The new range of MacBooks, being announced as part of a big “hello again” presentation of “new stuff” on 27th October, not only remove the cheapest 11-inch MacBook Air option from the market, but also only have USB-C sockets, taking away the old standard USB-A sockets. The SD-card sockets are also gone, although we do get a touch-screen “magic toolbar” bar at the top of the keyboard, replacing the F-keys, and a fingerprint scanner button has been sighted in leaked pics. New Skylake processors and/or mobile Xeon E3 chips may be introduced which could force up costs – a problem with Apple computers already compared to the opposition.

In truth, many industry observers are now detecting a slowdown in what actually changes from model to model as each new version comes onto the market. For devices such as the industry-standard MacBook Pro, the new changes will be the first since 2013 and the leaked pics hardly suggest a dramatic change this time around. Operating software upgrades, such as the new iOS 10.1, seem to contain less that is really new or wanted each time. Apple did hope that the iWatch smart watch device, introduced in 2014, might be the next big thing, but the sales of these have not proved as popular as was the case with iPads or iPods when they first came out.

And so the storm clouds are starting to appear in the numbers. Firms like Apple are having to look at their rising research and development costs and have started “revising” production targets. Meanwhile, the warehouse mountains of tech goods are getting larger and larger. Ironically, from being the industry which bucked the trend during the recent crisis, the consumer technology sector may now become its most high-profile example.

Technology and revolution

The huge advances in technology over the last few decades should have provided the basis for rising living standards and a better society. However, for the full potential of technological advances to be realised, we need socialism: a system that could utilise these advances to plan production and distribution for the benefit of all. Instead, we have billions of smartphones, laptops and a plethora of other gadgets, on the one hand; and yet, on the other hand, people are living in poverty, facing basic problems of hunger, sickness, and homelessness on a daily basis.

At the end of the day, you cannot live inside a smartphone or eat it if you are hungry. Capitalism – with private property, competition, and production for profit – has become an enormous barrier to continued development of science and technology. To have a further technological revolution in society, we need a socialist one!