Context and summary

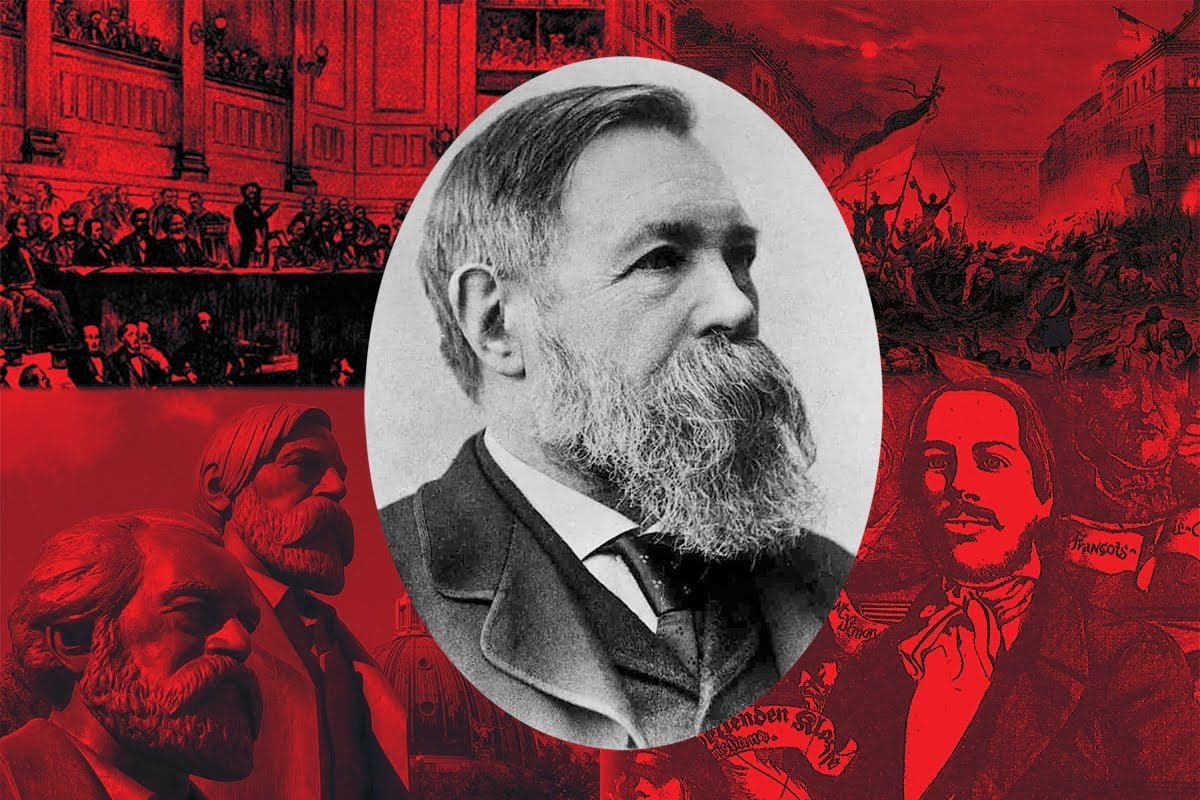

Originally (and sarcastically) titled “Herr Dühring’s Revolution in Science”, but more commonly known as “Anti-Dühring”, Engels’ monumental polemic against Prussian philosopher Eugen Dühring stands the test of time and remains one of the most complete outlines of the Marxist method that can be found in one volume.

It was written in response to Dühring’s works in which he claims to have created “a new mode of thought”, “system creating ideas”, and a “strictly scientific conception of things and men” all with what he proudly announces to be “from the ground up, original conclusions and views.”

In 1874 the German Social-Democratic Party (SPD) published an article in their newspaper by the prominent leader August Bebel, in favour of Dühring’s work. His ideas began to gain some popularity. At this point Marx and Engels had worked tirelessly to provide the working class with a scientific theory of their struggle, and through their clarity and patience had won significant sections of the workers organisations of Europe to their method and programme.

In a series of letters to one another they decided that a theoretical response to Dühring was necessary to keep the workers’ movement, particularly in Germany, based on a scientific and proletarian philosophy.

Anti-Dühring was according to Engels an attempt “to produce an encyclopaedic survey of our conception of the philosophical, natural-science and historical problems.” From a foundation of philosophy, Engels counters Dühring’s idealism with the philosophy of dialectic materialism. Through nature, to morality and then dialectics in general, Engels derives his method for an incredibly thorough analysis of political economy. The detail with which Engels describes real, concrete relations and historical processes, from which he draws his conclusions, is in marked contrast to the lazy assertions and abstract generalisations of Dühring. It is a truly remarkable demonstration of historical materialism at work.

Introduction: I & II (I.General) (II. What Herr Dühring Promises)

Herr Dühring’s initial claims in philosophy

3 fields of thought:

- The universe

- The realm of nature

- The realm of humankind

The development of thought:

Human thought generally forms certain patterns and trends. General ideas and world outlooks can be categorized into different schools of thought. These ideas take hold in such a way because they are in fact a general expression of the social and material interests of a certain class or layer of society.

The ruling ideas in society are always the ideas of the ruling class. But contrary philosophies emerge – the class struggle expressed on the ideological plain. The philosophies developed by other classes in different material conditions, do not hold good for the working class.

The dramatic change in material relations brings with it a dramatic change in world outlook. A new philosophy is developed. In the bourgeois period, a new class emerged onto the scene of history, the working class. The working class therefore, taking in the new world around it and its new social relations, must develop its own world outlook and philosophy, and all this at a time of immensely advanced knowledge and scientific method. For the first time in history, a class was able to express its world outlook scientifically.

Marxism is a proletarian outlook, because it bases itself on the interests of the working class, understood scientifically and in their totality.

Study questions and prompts:

- Can any idea take hold in society at any time?

- Why was the dialectics of the classical ancient Greeks described by Engels as a “primitive, naive, but intrinsically correct conception of the world?”

- What is the difference between metaphysical and dialectical thought?

- How did metaphysical thought enter into the field of philosophy?

- What was the most significant contribution made by Hegel to philosophy?

- What was the basis for the limitations of the Hegelian philosophy?

Part 1 – Philosophy

Philosophy: III. Classification and Apriorism

The question that Engels chooses as his starting point is the nature of knowledge itself, and types of thought.

Materialism and idealism are introduced as the two most general types of thought. The chapter deals with questions such as logic, mathematics, classification, and asking: what is their essence? How do they work? Why do they work? Where do we get them from? In doing this Engels tries to show the true relation between the material world and human thought.

Dühring states that:

“In pure mathematics the mind deals “with its own free creations and imaginations”; the concepts of number and figure are “the adequate object of that pure science which it can create of itself”, and hence it has a “validity which is independent of particular experience and of the real content of the world”.”

Engels, however, insists on a materialist approach:

“Like all other sciences, mathematics arose out of the needs of men: from the measurement of land and the content of vessels, from the computation of time and from mechanics.”

Study questions and prompts:

- Why is the idea of ‘universal truths’ or the idea that ‘the realm of pure thought is limited to logical schemata and mathematical forms’ an idealist mode of thought?

- What is the similarity between Hegel’s ‘Philosophy of mind’ and Dühring’s ‘inner logical sequence’?

- Does this mean that Marxists oppose the validity of logic?

- Why is the supposed existence of universal truth antithetical to actual human thought?

- In what way is Dühring’s conception of mathematics upside down?

- What is the basic reason that our system of mathematics and hypothetical geometry can be accurately applied to the material world?

Philosophy: IV. World Schematism

Dühring uses the difference between non-sensation and sensation as an example of qualitative difference (differentiation in the genus of things) as having no relation to the magnitude (or quantity).

I.e. things can be differentiated by quality firstly and then measured by magnitude secondly. According to Dühring, these are the scientific and mathematical truths of knowledge and therefore are the fundamental truths of reality. When expressed in this way it is clearly an idealist conception of reality.

Engels argues that although this is how we sometimes classify and measure things; in reality all things are composed of matter, and all matter is arranged in different quantities and ratios giving it different qualities. It is from that reality that we then are able to define genus, then species and then finally, measure magnitudes of various properties within the range of that qualitatively determined category (genus or species).

Study questions and prompts:

- What is materialism?

- Why does Engels argue that Dühring’s ‘schematism of categorisation’ is the same as that of Hegel?

- How do quantity and quality relate?

Philosophy of Nature: V. Time and Space

Dühring struggles with the concept of infinity. He attempts to use formal logic to prove that time and space cannot have always existed in the past as all infinite series (as in mathematics) must have a starting point and therefore can only be infinite in 1 direction.

Engels points out that in reality nothing can be understood in only 1 direction, as it is elementary that the real world has 3 dimensions and each dimension has 2 directions.

Kant, far before Dühring, pointed out that formal logic can be used to both prove infinity and to disprove it. Upon this foundation Hegel stated that infinity can be understood only by accepting that contradiction is inherent to it.

Dühring argues that time is only measurable in the sense that we break down motion into digestible and relative units, which is correct. But he uses this along with the assertion that time cannot be traced back infinitely (nor ‘causes’, celestial bodies, or particles of matter), to conclude that matter must therefore have had an original, unchanging state of being, and therefore time has a starting point when the process of change and motion is commenced.

This is a classic example of a-priori philosophy: making assertions about reality to fit your a-priori model.

Study Questions and prompts:

- What is wrong with the analogy between infinite space-time and an infinite mathematical series?

- What is Engels’ argument against Dühring’s conception of a self-equal state of being?

- How does this relate to creationism?

- How does this relate to the theory of the Big Bang as a singularity?

Philosophy of Nature: VI. Cosmology, Physics, Chemistry

For much of this chapter, Engels takes a closer look at Dühring’s method regarding the nature and origins of matter and the universe.

Firstly Engels addresses Dühring’s dismissal of previous philosophers, such as Kant, because his theory could not answer every question which arises from it. Although Kant’s theory was not complete (as no theory or model of reality ever can be), Engels explains that “The Kantian theory of the origin of all existing celestial bodies from rotating nebular masses was the greatest advance made by astronomy since Copernicus.” This is because his theory introduced the idea that nature itself had a history, and a process of development, and that even matter and energy have known different states of being. This was revolutionary in that it challenged some of the fundamental assumptions and assertions, and opened the door to new questions and the possibility of a whole new field of investigation into the laws of matter and motion. It has since become an undisputed fact that forms of matter that we are familiar with have indeed developed from an unfamiliar universe of gas clouds and nebulous masses. The mechanisms that governed their development are of course far more complex than Kant was able to explain or even conceive of. And yet through his incomplete yet generally correct theory, this mechanism can be discovered, investigated, and now explained in detail.

The general mistake that underpins Dühring’s false theories is once again a-priori reasoning. He asserts that the evolution of matter through different stages must have an original stage. The ‘primordial, self-equaling state’ of rest. The ‘unity of matter and mechanical force’. This assertion is not based on an analysis of the real stages of development that can be investigated, but is rather based on a ‘logical-real formula’ that must underpin his ‘world medium’.

Engels points out that Dühring’s method is not only flawed, but also not as original as he suggests. Engels does this by comparing his theory to the philosophical categories of Hegel: “What we have gained by this is not any proof of the reality of that fantastic primordial state, but only the fact that it is possible to bring this state under the Hegelian category of “in itself”, and its equally fantastic termination under the category of “for itself”.

Study questions and prompts:

- Explain how and where Dühring’s method falls into a-priorism again.

- Consider how Engels’ method differs from this.

- What is the relationship between motion, rest, and mechanical energy?

Philosophy of Nature: VII. The Organic World

In the previous chapter, Dühring is shown to dismiss Kant’s contributions to cosmology, for not explaining the precise mechanisms within it. Similarly, in this chapter, Dühring rejects Darwinism for not explaining the cause of variation: “But Darwinism “produces its transformations and differences out of nothing.”

In attempting to highlight the flaws in Darwinism, Dühring exposes that he has not fully understood the distinction between the process of evolution, which amounts to ‘unconscious purposive activity’, and the process that causes new variations to emerge in the first place.

Study questions and prompts:

- What does Engels mean by the term ‘unconscious purposive activity’?

- How does this relate to evolution and adaptation?

- How does this relate to the dialectical relationship of necessity and accident?

- Can something have a ‘purpose’ without conscious intervention of ideas?

- What is the misconception made by Dühring (and others) about the process of natural selection?

Philosophy of Nature: VIII. The Organic World (continued)

Engels begins this chapter by examining the types of categories we use to define the variations in the organic world. He examines how they are derived, what their usefulness is and their limitations. He does this with relation to the categories of plant and animal. As the organic world is under a constant process of change and development, intermediate forms between categories can exist and exceptions can exist that cannot be placed within a clear category. Engels explains that this does not necessarily mean that those categories, such as plant and animal, are therefore of no relevance or usefulness whatsoever.

He then goes on to look more concretely at the processes underpinning life. Using the limited knowledge available at the time, Engels attempts to give an explanation of life in its most general terms: “Life is the mode of existence of certain chemical forms (‘albuminous bodies’)”. We can see in his method a scientific and sober approach, and the dialectical method of explaining life as a process (the mode of existence), rather than defining it as a list of fixed qualities.

Study questions and prompts:

- What is meant by the term ‘development’?

- How does this relate to nature?

- How could this relate to human society and history?

- How does Engels’ method differ from Dühring’s when attempting to study the phenomenon of life?

- “But what are these universal phenomena of life which are equally present among all living organisms?”

- What are the purposes and limitations of our categorisations and definitions?

- regarding life forms in nature?

- in general?

Morality and Law: IX. Eternal Truths

When discussing the question of morality, the difference between materialism and idealism really becomes clear in their relation to practical political life.

Dühring’s idealist method makes the claim that morality can stand “above history and also above the present differences in national characteristics.” This is not an uncommon view, nor is the opposite position; that morality is entirely subjective, individual, and therefore ‘not real’.

He also asserts that there is such thing as ‘eternal truths’ in general: “it is altogether stupid to think that the correctness of knowledge is something that can be affected by time and changes in reality”.

Throughout the text Dühring claims to have created “a new mode of thought”, “system creating ideas”, and a “strictly scientific conception of things and men”. Dühring claims to have done this all with “from the ground up, original conclusions and views.”

This in itself should be a warning sign for those pursuing a scientific method. As Engels is quick to point out, the nature of science is that things are discovered cumulatively, and that our understanding and knowledge in fact comes from a continuous “series of relative errors”. Through a scientific method, the more that humankind experiences, passes on, and discovers about reality, the more our misunderstandings are revealed to us and our conceptions corrected. The idea that Dühring himself, from purely original thought, without inheriting anything from the great thinkers of the past, has discovered “a final and ultimate truth” is unscientific from the outset.

In contrast to Dühring’s indiscriminate insulting of various philosophical pioneers, the method of Marx and Engels was knowingly developed upon the shoulders of great thinkers of the past, whose contributions to a closer understanding of nature and thought were greatly appreciated and admired by the founders of scientific socialism.

Through their analysis of the actual development of human thought over “time and changes in reality”, Marx and Engels placed the notion of truth back in its real context. The dialectical method allows them to arrive at the understanding that human thought can only be true in terms of how well it applies to reality. As reality changes, various truths will inevitably become false and vice-versa. Human thought is therefore always incomplete and yet developing. Human thought cannot reach an ultimate or final truth, yet this does not mean that some ideas cannot be true where others are false.

In the latter part of the chapter Engels places morality on a material basis. He examines various trends of morality and shows how they are the product of generalised class interests. The experience and material needs of the working class cannot be satisfied by the morality of capitalist relations. Just as the material needs of the bourgeoisie could not be satisfied by the morality of feudal relations.

Revolutions in morality express the beginnings of a growing need for a revolution in social relations.

“We therefore reject every attempt to impose on us any moral dogma whatsoever as an eternal, ultimate and for ever immutable ethical law… A really human morality which stands above class antagonisms and above any recollection of them becomes possible only at a stage of society which has not only overcome class antagonisms but has even forgotten them in practical life.”

Study questions and prompts:

- What does Engels mean when he says “we have not yet passed beyond class morality”?

- What are some fundamental differences between bourgeois morality and a proletarian morality?

- How do these moralities arise from their respective class conditions?

- Why is proletarian morality the morality of the future?

- Is proletarian morality as it exists under capitalism the same as proletarian morality would be under socialism?

- What is the contradiction between human thought in general and the thought of individual humans?

- With this in mind:

- Can human thought be sovereign?

- Is human thought limited?

- Can any morals be absolute or eternal?

Morality and Law: X. Equality

Engels dedicates a whole chapter to the question of equality. This is because the moral concept of equality has been of particular importance in the course of the class struggle since the enlightenment. It serves as a very good example of how moral concepts are based on class interests.

Once again, Dühring is off to a false start due to the same idealist starting point. He focuses on the abstract concept of the thing and tries to define equality in those terms.

Engels responds with a very interesting history of the origins of the concept of equality, and the way it has evolved. He shows how the idea of equality as a political demand evolved with the development of real inequalities that take on a general form, and more importantly, the material feasibility of political or legal equality.

Study questions and prompts:

- Dühring tries to characterise the basic forms of moral justice from an abstract, imaginary scenario involving only 2 people. He asserts that ‘two human wills are as such entirely equal.

- What are some of the main problems with this method?

- Why is this another example of a-priori reasoning?

- Why could there be no talk of general equality of men in the ancient Greek or Roman society?

- Under the feudal political structure, the economic conditions of life developed into bourgeois relations.

- Consider how this process took place.

- What effect did this process have on political demands and morality?

- How did the notions of freedom and equality come to be considered ‘human rights’?

- Regarding the demand for equality, what does Engels mean when he says that ‘the proletarians took the bourgeoisie at its word’?

- What are the two meanings of the proletarian demand for equality?

- What does Engels mean when he says that the proletarian demand for equality ‘stands or falls with bourgeois equality itself’?

- What is the ‘real content of the proletarian demand for equality’?

Morality and Law: XI. Freedom and Necessity

When discussing freedom, we must be concrete. Freedom from what? Humans, like all living organisms, are not free of the need to nourish and replenish themselves. In the process of development, primarily the development of the productive forces, we have freed ourselves from many of our former obligations set by nature. The vast majority of us are free from the obligation of crafting our own tools and clothing in order to survive. But for many this has been replaced with the gruelling necessity of working longer hours for a capitalist master.

Engels explains that we can therefore only have relative freedom; to make a choice within given parameters. Humanity in general discovers new freedoms by accumulating knowledge of the natural laws and necessities imposed on us and “systematically making them work for us”:

“Freedom therefore consists in the control over ourselves and over external nature, a control founded on knowledge of natural necessity.”

Study questions and prompts:

- What does Engels mean by freedom?

- What is the relationship between freedom and necessity?

Dialectics: XII. Quantity and Quality

In Dühring’s work, he directly criticises Marx’s method of dialectical materialism. One of these criticisms is against the theory of quantitative changes becoming qualitative transformations. In particular he dismisses Marx’s example of capital being the qualitative transformation resulting from the quantitative accumulation of money. Dühring objects to these theories, accusing Marx of reducing everything to ‘one and the same thing’:

“How comical is the reference to the confused, hazy Hegelian notion that quantity changes into quality, and that therefore an advance, when it reaches a certain size, becomes capital by this quantitative increase alone.”

However, Marxism does not claim that ‘quantitative increases alone’ – in an automatic way – are all that are required to explain such transformations. In fact, what distinguishes the theories of Marx and Engels from Dühring’s is that they are not based on a-priori assertions, but they are extracted from a close study of the process in question.

To take the example of the transformation of quantity into quality; they do not draw this conclusion to fit their world view. The conclusion is drawn from observation.

For instance; we know it to be so, that different elements are made up of different combinations and different quantities of the same subatomic particles. We know that 6 carbon atoms connected to 6 hydrogen atoms makes Benzene while 1 carbon atom connected to 4 hydrogen atoms makes methane; chemicals with qualitative differences.

We know that a molecule of methane behaves in a qualitatively different way (mechanically and otherwise) to a whole gas cloud of methane molecules.

And we know that a quantitative increase in methane molecules leads to a change in temperature and can even have a qualitative change in the weather systems, seasonality, and the rate of temperature change itself.

At all levels of reality, the phenomenon of quantitative changes tipping over into qualitative transformations is observable. It is from this reality that we consider it a law.

This can also be seen in human relations.

Now we can return to this tendency of the transformation from a quantitative increase of currency, into the ability to apply it as capital (a qualitatively different phenomenon). Under certain conditions, a given quantity of money becomes something qualitatively new – capital. But under this quantitative threshold, it cannot become capital.

Study questions and prompts:

- What do we mean by the term contradiction? What are some examples of contradictions in nature?

- What is the contradiction inherent in motion?

- How does a quantitative increase produce the qualitative transformation into capital?

- What are some examples where we find quantitative changes producing qualitative changes?

Dialectics: XIII. Negation of the Negation

One of the most fundamental, underlying characteristics of Marxist Philosophy (Dialectical Materialism) is that it seeks to explain processes. It seeks to look at things in their motion. It is a philosophy of change; from quantity to quality; the motion of matter; its constant change and development. After a long examination of various fields of thought and nature, it is fitting that the last chapters of this section seek to draw out the most general patterns of change.

As was explained throughout this section of the book, contradiction is inherent to change, and is in fact its continuous driving force: opposing forces lead to both gradual change and revolutionary tipping points. The negation of the negation is one of these patterns of change, and can help us to understand which processes are in opposition to others; which one will overcome the other; what the driving force of the process in question is. From this philosophical foundation, historical analysis and practical political life can be based on the actual process in question. It is this that allowed Marx and Engels to reveal that the abolition, or ‘negation’, of capital is not in fact a utopian creation of the mind, but a necessary outcome of the development of labour. The basis for this particular conclusion is dealt with in the two subsequent sections on ‘Political Economy’ and on ‘Socialism’.

Study Questions and Prompts:

- What is the difference between the way that Marx identified the law of the negation of the negation, compared with the straw-man that Dühring is arguing against?

- What does Marx mean by the negation of the negation, with respect to private property?

- Describe the way in which this process developed.

- What are some examples of the negation of the negation in other processes?

- What does Engels mean by the term ’laws of motion’? What is the usefulness of understanding the negation of the negation?

Part 2 – Political Economy

Chapter 1 – Subject Matter and Method

In this chapter, Engels explains the Marxist approach to Political Economy and attempts to uncover the concrete material laws that govern production, distribution and exchange and explain how these have evolved historically through various stages of society. Political economy, Engels explains, is “the science of the laws governing the production and exchange of the material means of subsistence in human society” (pg. 177).

Engels emphasises that these laws are not static, as the conditions of production and exchange vary in time and place; thus, political economy is a historical science that deals with constantly changing material. General laws, therefore, can only be developed through an investigation of the specific laws of each stage of production.

Engels explains that the mode of production and exchange within a given society determines distribution. For example, in a tribal or village community – where there is no private ownership, only communal ownership of the means of production – distribution is fairly equal. When distribution is not equal, this is a reflection of the existence of class differences within a society. Capitalism has very rapidly created extreme inequality in distribution as a result of the concentration of capital in the hands of an increasingly tiny minority on the one hand, whilst on the other hand a concentration of propertyless masses.

Engels also explains that this mode of distribution, along with the political institutions that uphold it, will at a certain stage of development act as a brake on the development of the mode of production. This is the stage that capitalism has reached today, where alongside enormous reserves of wealth there are stagnant means of production and an enormous labour force that cannot be put together in a profitable way. Thus, production and exchange have a dialectical relationship with distribution, distribution is a product of the prevailing modes of production and exchange within a given society but in turn it acts back upon the modes of production and exchange.

Dühring, however, as with his philosophy, claims to have found “the most general laws of nature governing all economics.” (pg. 183) Dühring divorces the connection between production and exchange and distribution, claiming that they act independent from one another. He then eliminates the need to explain different historical forms of distribution by claiming that they all rest solely on force, a question which Engels deals with at length in the next few chapters. He thus transfers the entire theory of distribution from a question of concrete material laws to one of morality. As Engels explains: “he therefore no longer has any need to investigate or to prove things; he can go on declaiming to his heart’s content and demand that the distribution of the products of labour should be regulated, not in accordance with its real causes, but in accordance with what seems ethical and just to him” (pg. 187-8).

This approach to the question of distribution is not unique to Dühring. In fact the idea that distribution under capitalism is fundamentally a moral rather than an economic question is the dominant theory of the reformist left who, for example, see austerity as simply a political choice rather than a requirement based on the logic of capitalism.

Engels explains that if all we had to rely on for the impending overthrow of the capitalist system was consciousness of the fact that the system was “unjust”, then the task of the revolutionary transformation of society would appear impossible. In truth, it is the objective economic developments that lay the ground for the overthrow of capitalism – the development of the working class, which can play the revolutionary role of overhauling society, and the crises that show the capitalist class is no longer capable of controlling the productive forces and advancing society.

Study questions and prompts:

- What is the relationship between production, distribution and exchange?

- Is it possible to find ‘general laws’ of political economy?

- In what way does the capitalist mode of distribution and the political institutions of capitalism retard the development of the productive forces of society?

- Similarly, in what way did the feudal mode of distribution and political institutions hold back the development of capitalism?

- Why is distribution a question of concrete economic laws and not simply a question of morality?

- Why is understanding these economic laws so vital when it comes to the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system?

Chapter 2 – The Force Theory

In the second chapter on Political Economy, Engels challenges Dühring’s “force theory”. Dühring subjects economics to political conditions, claiming that direct political force explains distribution in any given society. As an allegory, Dühring uses the example of Robinson Crusoe and his enslavement of Friday, which was achieved through force as Crusoe physically compelled Friday to produce for him.

Engels, however, explains that the act of enslavement itself has certain preconditions – production must have reached such a level to provide the instruments and material for the slave’s labour and the means of bare subsistence for him. For slave labour to become the dominant mode of production for a whole society there must be a certain level of production, trade and accumulation of wealth. Engels explains that in early, pre-class societies, not only was there not the material capacity for the enslavement of large parts of the population, there also was not the will – only when labour becomes productive enough to produce a surplus does there become a logic to the enslavement of parts of the population.

Engels uses the example of Rome which was originally a peasant city. Only once it became a “world city” and land ownership was centralised into a small number of wealthy proprietors, was the peasant population supplanted by slaves. Therefore, it was the development of the productive forces – of a highly developed handicraft industry and extensive commerce – that laid the basis for the development of slavery. Force was simply the means by which the economic interests of the developing ruling class could be realised.

Furthermore, if the advent of slavery requires a certain level of production before it can be enacted through force, how is it that society can reach such a level? Engels explained that it must have been created through labour. Private property, Engels says, existed – to a limited extent – even within primitive communes. This developed into production of commodities within those communities for barter with other communities. As more products assume commodity form and the more the natural division of labour was extruded by exchange within the commune, the more inequality developed in ownership of property, out of which formed classes.

It is the class struggle, which expresses the contradictions within any given mode of production, that drives history forward. Political force is simply the means of maintaining the class divisions that exist within any given society. Engels explains that if, as Dühring argues, “political conditions are the decisive cause of the economic situation,” then the bourgeoisie could never have conquered power in their struggle against the feudal nobility. Political power rested solely in the hands of feudal nobility throughout the whole period; however, development of the bourgeois mode of production had outgrown the political institutions of feudalism. Guild privileges and customs barriers had become a fetter on the development of the growing bourgeois market, so the bourgeois class did away with the political situation in order to meet the economic needs of their class.

In the same way, political force today rests in the hands of the capitalist class, in the state – or ‘armed bodies of men’. The power that rests within the hands of the proletariat is not military power but economic power. It is only with the kind permission of the working class that capitalism is able to function. If the working class organises, however, and takes conscious control of the means of production – including, for example, the means to produce weapons – then they can use this to cast out the capitalists and to smash the bourgeois state. If all that mattered was who had political force at a given time then the proletarian revolution would be doomed from the outset.

Study questions and prompts:

- Why can the ‘force theory’ not explain the existence of pre-class society?

- What are the preconditions necessary for the development of class society?

- How do the bourgeois revolutions demonstrate the inadequacies of the ‘force theory’?

- If inequality cannot be explained by the use of political force, how can it be explained?

Chapter 3 – The Force Theory (Continuation)

In this chapter, Engels explains that not only is force simply the – or, in fact, a – means through which to enact the economic interests of classes within society, but the use of force is also itself determined by the productive capacity of society, and thereby the economic conditions. In reference to Dühring’s allegory with Crusoe and Friday, Engels simply asks: Where did Crusoe get the sword? For the use of force for the subjugation of a part of the population must as a basic precondition require the development of a society with the productive capacity to produce the weaponry required to wield such force. As Engels jibes: “if Crusoe could procure a sword for himself, we are equally entitled to assume that one fine morning Friday might appear with a loaded revolver in his hand, and then the whole ‘force’ relationship is inverted.” (pg. 199)

Force is not merely an “act of will”, it requires certain preliminary conditions before it can operate and the production of the necessary instruments. The triumph of force is therefore the triumph of arms and of production in general, therefore the triumph of economic power. Force is incapable of creating wealth, in fact it depends on already existing wealth in order to be sustained. As Engels explains: “nothing is more dependent on economic prerequisites than precisely army and navy. Armament, composition, organisation, tactics and strategy depend above all on the stage reached at the time of production.” (pg. 200)

The invention of gunpowder, which came via the Middle East in the early fourteenth century, revolutionized the methods of warfare through the creation of firearms. This was not an act of force but the advancement of industry. The production of these firearms required both money and industry, both of which, Engels explained, rested in the hands of the burghers of the towns. Engels writes: “the stone walls of the nobleman’s castle, hitherto unapproachable, fell before the cannon of the burghers, and the bullets of the burgers’ arquebuses pierced the armour of the knights. With the defeat of the nobility’s armour-clad cavalry, the nobility’s supremacy was broken.” (pg. 201) Thus, it was not mere force that broke the power of the feudal nobility, but the economic development within the towns that provided the necessary instruments with which the rising burghers were able to smash the nobility.

Study questions and prompts:

- What is wrong with Dühring’s allegory wherein Crusoe enslaves Friday with a sword?

- Why is military power dependent on the development of the productive forces?

- How did the bourgeoisie overcome the political power of the feudal nobility?

Chapter 4 – The Force Theory (Conclusion)

In this chapter, Engels demonstrates that Dühring’s force theory can in no way explain the historical development of society and that, in fact, it is the development of the productive forces and the class struggle that act as the motor force of history. Central to Dühring’s theory that inequality in society is simply the result of the use of force is the idea that the domination of nature by man presupposes the domination of man by man. Dühring explains that cultivation of landed property in tracts of considerable size never took place without bondmen because there cannot be large landowners without bondmen since they and their family could only work a tiny part of the property. Dühring’s claim is that ‘nature’ was transformed into ‘landed property in tracts of considerable size’ with no stages in between and that this was immediately transformed into the property of the landowners.

Engels, however, explains that landed property originated in tribal and village communities that maintained common ownership. In India, he notes, this was the norm right up until colonial rule. In the Middle ages, peasant farming was the predominant form of agricultural production across Europe. In fact, Engels notes, far from advancing the process of cultivation, the big landlord has historically played the role of undermining the productivity of land. Engles explains: “where he does make his appearance in antiquity, as in Italy, he does not bring wasteland into cultivation, but transforms arable land brought under cultivation by peasants into stock pastures, depopulating and ruining whole countries.” (pg. 212)

Dühring has once again abstracted laws from the society in which he lives and tried to impose those onto the whole of human history, with “unprecedented ignorance” and a complete disregard for history.

Dühring’s theory that the history of society can all be explained simply by force is, in a distorted way, an acceptance of the class nature of society. However, it is so general that it can in no way explain the classes and the contradictions within any given society. It cannot, for example, explain the origin of capitalism, or explain how or why it functions in a way that is distinct from previous forms of class society. Moreover, as Engels explains “the mere fact that the ruled and exploited have at all times been far more numerous than the rulers and the exploiters, and that therefore it is in the hands of the former that the real force has reposed, is enough to demonstrate the absurdity of the whole force theory.” (pg. 214)

Engels goes on to explain how class relations actually developed. In prehistoric hunter-gatherer tribes, he explains, there was an equality of social positions, although certain roles may be given to specific individuals, i.e. adjudication of disputes, control of water supplies, religious functions etc. As the productive forces of society advances, however, the increasing population density creates both common and conflicting interests between communities, out of which develops the need for certain organs to safeguard the common interests and combat conflicting ones. These organs hold a special position and soon make themselves independent through, for example, a heredity of functions. As Engels describes: “the exercise of a social function was everywhere the basis of political supremacy.” (pg. 215)

Only once production developed to the point at which the labour power of one person can produce more than that required for subsistence did labour power acquire a value. However, at this stage, the community provided no available, superfluous sources of labour. War, and the capture of slaves from neighbouring communities, became the source of this labour. Therefore, force was able to provide a vital service to the economic situation, but it was the economic development of society that set things in motion. Slavery, by making possible the division of labour between agriculture and industry, marked an enormous step forward in the productive forces of society at that time.

Ultimately, Engels explains that force does play a role in the development of society, in that it can be wielded to either accelerate or slow economic development. Force does not only play the role of maintaining the domination of the ruling class over the rest of society, it can also play a revolutionary role in overthrowing the social formation that has become a fetter on the economic development of society. The key point, however, is that the use of force is not primary, in the first place it depends upon the development of the productive forces, the creation of instruments of force and therefore on the economic development of society. Furthermore, it is the economic developments that create the class divisions within society, that create the need for the use of force. Only by studying the economic laws that govern society, understanding how they function and where they come into contradiction, can we understand how to take conscious control of the productive forces.

Study questions and prompts:

- What is wrong with Dühring’s assertion that the dominance of man over nature must be preceded by the domination of man over man?

- What are the implications on the class struggle today of the idea that class society is purely a result of political force and not objective economic laws?

- How and why did class society develop out of hunter-gatherer society?

- What role does force play within the development of society?

Chapter 5 – Theory of Value

This chapter is the first in which Engels explains the Marxist approach to political economy. Engels outlines the Labour theory of value in opposition to Dühring’s force theory. According to Dühring, wealth is the governing concept in political economy and wealth itself consists of “economic power over men and things.” Engels explains that this is wrong for two reasons – firstly, because wealth existed in tribal and village communities not through domination of men over men. Secondly, because in class society, wealth obtained through domination over men is possible only by virtue of the domination of things, by the control of the ruling class over the means of production.

Once again, Dühring has attempted to drag economic questions into the domain of morality. As Engels explains: according to Dühring “domination over things is quite all right, but domination over men is evil; and as Herr Dühring has forbidden himself to explain domination over men by domination over things, he can once again do an audacious trick and explain domination over men offhand by his beloved force.” (pg. 223) If wealth is domination over men then wealth is “robbery” and therefore immoral, or so Dühring argues.

Through this trick, Dühring has divided the concept of wealth into two separate aspects: production and distribution. Wealth as domination over things – or production – is moral. Whilst wealth as domination over men – or distribution – is immoral. Therefore, the capitalist mode of production is fine and can remain, it is just the mode of distribution that must change. This leads directly to reformism, the idea that the working class need not overthrow the entire economic system but simply fight for a fairer distribution of the product of society.

Dühring then provides an extremely confused definition of value, where in the one instance it is defined in relation to price – which Dühring describes as the monetary expression of value – and in another as determined by the labour-time necessary for production. This, Engels explains, is false. If value was determined purely by the labour-time put into the creation of a commodity that would mean the value of something with no use-value – such as mud-pies – would be equivalent to the value of something with enormous use-value – like items of food – simply because the labour-time put into each was equivalent. Furthermore, if one person spent 4 hours producing a commodity by hand, whilst another produced 10 of the same commodity in the same time by using machinery, clearly the value of the one commodity would not be equivalent to that of the 10 commodities.

Dühring, in addition, claims that a part of the value of any commodity is also the tax surcharge, which is imposed “sword in hand.” In other words all value, according to Dühring, is a monopoly price. Engels explains that if all commodities have such a monopoly price, either each individual loses as a buyer what he gained as a seller – which would mean that the price remains the same in relative terms. Or, on the other hand, what Dühring describes as “tax surcharges” are in fact the unpaid labour of the value producing class – meaning we arrive at Marx’s theory of surplus value, which Engels explains at length in later chapters.

Engels explains, therefore, that value cannot be determined simply by the labour-time, nor is it determined by tax surcharges demanded by the capitalists through force. In fact, value can only be determined through the “socially necessary general human labour embodied in them.” Therefore, value is a social average that reflects the general productive capacity of labour at any given time within a society. Significantly, workers are capable of producing in a day a value greater than the value of the means of subsistence required to keep them going. This surplus is the basis of all class societies. As Engels explains: “The whole development of human society beyond the stage of brute savagery begins on the day when the labour of the family created more products than were necessary for its maintenance, on the day when a portion of labour could be devoted to the production no longer of the mere means of subsistence, but of means of production.” (pg. 231)

Study Questions and prompts:

- Why can the mode of distribution not act independent of the mode of production? And therefore why is distribution based reformism impossible?

- What is the labour theory of value?

- How does Engels explain that profit under capitalism is not a result of force or ‘robbery’?

Chapter 6 – Simple and Compound Labour

In this short chapter, Engels tackles Dühring’s assertion that all labour-time is of equal value. According to Dühring “all labour-time is in principle and without exception absolutely equal in value”, and when the product of one person’s labour is unequal to another this can be explained by the fact that “the labour-time of other persons may be concealed in what appears to be only his own labour-time” (pg. 234) – i.e. within the prior manufacture of tools.

Engels explains that if all labour-time is equal in value that must mean that labour-time, and labour itself, has a value. However, it is labour that creates value, “value itself is nothing else than the expression of the socially necessary human labour materialised in an object” (pg. 238). Therefore, labour can have no value as it is the creator of value.

Engels argues that the claim of equality of value of labour-time would imply a universally equal production of value within a given time, however, this is clearly not the case. The value produced within a time period will vary greatly depending on many factors, most notably the intensity of work and the skill of the labourer. As Engels states “not even an economic commune can remedy this” (pg. 239). Dühring has taken up the demand of “equal wages for equal labour time” and to justify this moral demand is trying to impose onto the material world a situation where the labour of everyone in society is capable of producing the exact same value in a given time.

Engels explains that in a capitalist society, compound labour – that is more complex, skilled labour – is developed through the individual or family bearing the costs of training the worker and therefore the cost of the worker’s labour, their wage, is higher. In a socialist society, however these costs are borne by society to which belong the greater values produced by this compound labour. The worker does not receive extra pay, but the increased productivity of labour means that the surplus can be reinvested into increasing the productive capacity of society as a whole, meaning an increase in living standards. This shows the drawbacks of the demand that workers receive “the full proceeds of labour” which would mean no surplus to be reinvested into the development of the productive forces.

Study Questions and prompts:

- What is compound Labour? And how is it paid for in capitalist and socialist society respectively?

- What is wrong with Dühring’s claim that all workers’ labour-time is of equal value?

- What is wrong with the demand that workers should receive “the full proceeds of labour”?

Chapter 7 – Capital and Surplus Value

In this chapter, Engels explains Marx’s theory of surplus value which is central to understanding the way in which capitalism functions. In a characteristically lazy manner, Dühring tries to attack Marx’s theories on capital by claiming that Marx states that capital is “born of money.” Engels retorts that this is like saying that metallic money was born of cattle because cattle once functioned as money. Marx’s actual claim is that the “final product of the circulation of commodities is the first form in which capital appears.” This refers to the circulation of capital by which money – which is a universal equivalent representing the value of real commodities in relation to one another – is invested in production with the aim to sell the created commodities for a profit.

Engels explains that the circulation of capital is inverse to the circulation of commodities. The owner of commodities sells what he has in order to buy what he needs, whereas the capitalist buys what he does not need in order to sell and regain the value, with added surplus value. The key question is, from where is this surplus value derived?

Engels challenges a few common explanations for this – explanations which are still prevalent today. Firstly, he challenges the idea that profit is made by the capitalist either buying things from below their value or selling them at above their value (or indeed both at once). However, whilst there may be aspects of this process taking place within the real economy, Engels explains that this cannot be the root of profit because each capitalist is both buyer and seller, therefore any gains or losses cancel one another out. Secondly, Engels challenges the idea that profit is produced purely through cheating or trickery, which Engels explains would not augment the sum of value in circulation.

The conclusion at which Marx arrived, as Engels explains, is that the source of surplus value is labour-power. Labour-power describes the ability of the worker to labour. So the worker sells their Labour-power – their ability to labour, not their labour itself – for a part of the day as a commodity. The value of this commodity is determined by the labour-time required to produce the means of subsistence, to maintain the worker. Crucially, as Engels explains, “the value of the labour-power and the value which that labour-power creates, are two different magnitudes” (pg. 244) For example, the worker may be capable of producing in 4 hours an amount of value equivalent to that which they require to sustain themselves, however – since the capitalist owns the means of production upon which the worker depends to sustain themselves – the capitalist can demand the worker works another 4 hours in which time all the value created by the worker belongs to the capitalist. Therefore, profit can be created not through cheating or trickery but by an equal exchange of values, an exchange of money in the form of wages for the labour-power of the worker.

Engels explains that this situation is not natural but the product of previous historical developments. The relationship between capital and wage-labour requires, as a precondition, the creation of a class of free labourers – free in the sense that they are free to sell their labour power to the capitalist, but also free from the means of production and incapable of realizing their labour-power except through selling it to the capitalist.

Dühring is unable to explain this historical development and relies solely on his two men theory. As a result, he falls into the trap of seeing all cases of surplus-labour as capital – which would mean all forms of class society where one class exploits the other by expropriating the surplus-labour, i.e. slave society, feudalism etc, are all the same as capitalism. Engels explains that it is only when surplus-labour creates a surplus-value that it assumes the character of capital. Wealth is only capital when it is fused with labour-power in order to produce more wealth.

Study Questions and prompts:

- Why is profit not derived from simply buying low and selling high?

- What is labour-power?

- What is surplus value?

- What is capital?

- What historical preconditions are necessary for the circulation of capital to occur?

- In what way are previous forms of class society – such as feudalism and slave society – different from capitalism?

Chapter 8 – Capital and surplus value (conclusion)

In this short chapter, Engels explains the relationship between surplus value and profit. Dühring claims that Marx equates ‘surplus-value’ with the ‘earnings of capital’, or profit. However, Engels explains why this is not the case. There is no one-to-one relationship between surplus value and profit. Whilst profit is derived from surplus value, it does not account for surplus value in its entirety. Profit represents, as Engels describes it, “a subform and frequently only a fragment of surplus-value” (pg. 253). Engels explains that surplus-value is broken up into a number of forms of which profit is just one, other forms include rent and interest which take a chunk out of the surplus-value but do not represent a part of the circulation of capital and operate separately.

Dühring tries to claim that Marx insinuates that the capitalist, regardless of circumstances, always sells commodities at their full value. Engels explains that this is not the case, that Marx recognises, as one example, the fact that the manufacturer will often sell commodities to the merchant below their value, thus relinquishing a part of the surplus-value. Dühring also claims that Marx’s conception does not explain how competing entrepreneurs are able to constantly sell at a price above the “natural outlays of production” – an apparent gap that Dühring explains simply through the utilisation of force on the part of the ruling class. Engels explains that in the surplus-product, however, there are no “natural outlays of production” because the surplus-product is precisely that which costs nothing to the capitalist.

Dühring’s one-word explanation for profit, ground rent – force – explains precisely nothing. Force is incapable of creating value. Engels explains that within Dühring’s theory force distributes, but the question arises “force distributes what?.” Engels argues that “surely there must be something to distribute, or even the most omnipotent force, with the best will in the world, can distribute nothing. The earnings pocketed by the competing capitalists are something very tangible and solid. Force can seize them, but cannot produce them.”

Dühring’s attempt to relegate economics to the sphere of politics cannot explain a single economic fact.

Study Questions and prompts:

- Why are profit and surplus-value not equivalent?

- Why are there no “natural outlays of production”? How can commodities be sold at their real value and yet still yield a profit?

- What is wrong with Dühring’s attempt to explain economics solely in political terms, in terms of force?

Chapter 9 – Natural laws of economics: Ground-rent

In this chapter, Engels challenges Dühring’s claim to have found the “natural laws of national economy.” These “natural laws”, as with Dühring’s grand philosophical claims, amount to banal and self-evident statements such as: “the productivity of the economic instruments, natural resources and human energy is increased by inventions and discoveries” (pg. 264), which Dühring fashions into axioms that explain precisely nothing about the nature of the capitalist economy.

Engels then goes on to investigate Dühring’s concept of ground-rent. Engels explains that the theory of ground-rent is a specifically English part of political economy, since it was only in England where a mode of production existed where ground-rent was independent of profit and interest. In England, there existed three classes of bourgeois society – the landlord, drawing ground-rent, the capitalist, drawing profit and the labourer, drawing wages. Dühring claims that no clear explanation for the origin of the farmer’s earnings exists and suggests that these earnings are a kind of wage. Engels explains that not only are their earnings evidently profit derived from capital but that this position has been undisputed since the work of Adam Smith.

Essentially, Dühring’s concept of ground-rent sees the only difference between capital earnings and ground-rent as being the fact that ground-rent is derived from agriculture whilst capital earnings come from industry. This confused stance derives directly from Dühring’s “force theory.” As Engels explains, Dühring thinks that “as soon as land is cultivated by means of any form of subjugated labour, a surplus for the landlord arises, and this surplus is the rent, just as in industry the surplus labour product beyond what the labourer earns is the profit on capital. (pg. 269). Dühring defends his idea that rent forms the entire surplus product of agriculture by pretending the question of the division of agricultural income – the relationship between profit and ground-rent – has never previously been investigated and thus denies over a century of work on the question.

Study Questions and prompts:

- What is wrong with Dühring’s approach to political economy and his “natural laws of national economy”?

- Explain Dühring’s concept of ground-rent and the problems with it.

Chapter 10 – From the critical history

In this final chapter of the political economy section, Engels investigates the history of political economy. He explains that political economy reflected the scientific insights into the economics of the period of capitalist production but that certains principles and theorems had been found, for example, in Ancient Greek society where certain phenomena – such as commodity production, trade, money etc – exist within both societies. For example, Engels notes that Aristotle recognised the differentiation between the use value and exchange value of an object and that the role of money within society was as a measure of value. Engels explains that “because of this their views form, historically, the theoretical starting-points of the modern science” (pg. 271) Dühring, on the other hand claims that there is “absolutely nothing positive to report of antiquity concerning scientific economic theory” (pg. 271)

Dühring dismisses the work of Petty, not mentioning his proposition that labour and even labour-time are a measure of value, claiming that “imperfect traces can be found in his writings. Engels explains that Petty’s Treatise on Taxes and Contributions provides a clear and correct analysis of the magnitude of value of commodities, laying down “a definite and general form that the values of commodities must be measured by equal labour. (pg. 275).

In a similar way Dühring dismisses the contributions of many great bourgeois political economists such as Adam Smith, Boisguillebert, Locke, North etc. Only Hume manages to earn the respect of Herr Dühring, although Engels explains that whilst a competent economist Hume was certainly not original, or epoch-making and that his influence was reflection of the time his ideas were presented in – one of flourishing trade and a rapid rise of capitalism in England.

Dühring demonstrates an inability to understand the ideas of the Physiocrats, claiming that they “could offer nothing but confused and arbitrary conceptions, ascending to mysticism” (pg. 296). Engels explains that for their time they provided a “brilliant depiction of the annual process of reproduction through the medium of circulation” (pg. 296). Ultimately, Dühring’s Critical History, as Engels explains, sees all earlier economists either as providing the principles necessary for his deeper investigations, or as a foil to them. He does not recognise the profound contributions that have been made to the study of Political Economy or how the discipline has developed historically. Instead he finds the most minor, nitpicking points to attack them on, whilst dismissing many of the greatest contributions and claiming important questions have not been sufficiently investigated in order to advance his own lazy conceptions. Engels, on the other hand, recognises the contributions of these thinkers but also the limitations imposed upon them by their epoch, looking not to discard the ideas of the past but to build upon them.

Engels concludes by summing up the chapter. He explains that Dühring’s theory of political economy amounts to a con, with great promises that amount to nothing. Dühring’s “theory of value” consists of five different and contradictory sources of value, his “natural law of all economics” turn out to be empty platitudes and axioms that explain nothing; meanwhile his only real “explanation” is the one-word, cover-all “force” which without analysing its origins and effects he expects us to simply accept as the ultimate explanation of all economics.

Study Questions and prompts

- How should Marxists approach the ideas of the bourgeois economists of the early period of capitalism?

Part 3: Socialism

The first two chapters of this final part on “Socialism” were famously used by Engels for the pamphlet Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. As such, the notes below should be read in conjunction with our reading guide on this later, more polished exposition: which is linked above.

Chapter 1: Historical

Engels refers back to the Introduction, where he dealt with the rationalist French philosophers of the 18th century. The goal of a rational society, however, was nothing more than an idealised understanding of the “citizen” (burgher), who was evolving into the bourgeois. Eternal peace had turned into endless wars of conquest and the new rational society in practice only managed to deliver poverty and misery. Thus, compared with the splendid promises of the rationalist philosophers, the social and political institutions born of the “triumph of reason” were “bitterly disappointing caricatures.”

It was up to the great “Utopian” Socialists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries to formulate this disappointment. Providing a brief history of socialist thought from the early-modern era onwards, Engels traces the rationalist, democratic and communist movements of the period not simply as a battle of ideas, but rather of the theoretical expressions of the rise and conflict of newly emerging classes in society. Using the same method, Engels then turns to the first ideological shoots of the new-born working class in Britain and France: the “three great Utopians” of Saint-Simon, Jean-Baptiste Fourier and Robert Owen.

Analysing each of their theories in brief, Engels not only demonstrates the fatal flaws and limitations of their ideal “social systems”, but also places them in their historical context, of a class struggle (between the bourgeoisie and proletariat) which was only just coming into being and so, for that reason, still “crude” in its form and expression. This can be seen in the Utopians’ eschewing of the working class in favour of the “workers” or “people” in general.

However, Engels is by no means dismissive of the great intellectual and political contributions made by these individuals. He reserves his sharpest lines for those “Philistines” who “crow over the superiority of their own bald reasoning” over the “grand thoughts” of the Utopians. For Engels, there was much that was correct in their flawed theories, and much which was later inherited by Marx and himself.

Ultimately, from his treatment of the early and Utopian socialists Engels also puts Marxism in its own context as the product both of the theoretical products of earlier socialists, and of the modern proletariat in its full material development.

Study questions and prompts:

- Why were the institutions set up by the “triumph of reason” such “bitterly disappointing caricatures”?

- What unites all of the “three great Utopians”?

- How does “Modern Industry” make a revolution necessary?

- Why were the new social systems of the founders of Socialism “foredoomed as Utopian”?

- In what sense is politics “the science of production”?

- In what sense was Fourier’s conception of history dialectical?

- What similarities can we see between Owen’s philosophy and that of Marx?

- What were the limitations of Owen’s Communism?

- In what sense is Dühring practising “social alchemy” in his hunt for the “philosopher’s stone”?

Chapter 2: Theoretical

Engels begins this chapter by explaining that understanding material reality is the key to understanding society, that economic reality is the most important factor in determining society, not ideas. This, in essence, is the backbone of historical materialism.

Engels then identifies how capitalism came to be, taking the reader through the change from feudalism to capitalism and thus, the establishment of the modern bourgeoisie. He explains how the means of production were developed, and how the division of labour developed. Here we see a sudden jump into organisation, from the production of goods with the only purpose of need, to the organised factory that produced commodities to sell on the market. Previously, goods had belonged only to the person who made them, as only one person was generally responsible for production. This clear basis for ownership was no longer possible when any commodity was the product of many workers, and so private property came to mean the exploitation of those who worked but owned nothing.

Engels pins down that there must be an end to capitalism; redefining society not as a cycle, but a spiral that returns to previous points, only on a higher level. He goes back to the new and developed means of production, looking at how machinery will develop under capitalism. He speaks of overproduction, and explains why capitalism will overproduce, and more importantly, why this will become a scourge on the existence of capitalist society.

Moving on from this, the chapter then gives us an understanding of the state machine: what it is there for, and how it will wither away under socialism. “The state is not abolished. It dies out”, Engels explains.

Finally, Engels concretely lays out the history of states from Medieval Society to the future Proletarian Revolution. In doing so, he explains the importance of genuine scientific socialism.

Study questions and prompts:

- What major changes in the division of labour and productive forces have taken place in recent decades, and what political and social changes have been associated with these changes?

- How would you apply Engels’ observation that “the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in men’s better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange” to a major social movement of our times, such as the political polarisation across the West?

- Engels refers to the arrival of planned production with the factory system. Exactly what did he mean by this?

- Engels places a lot of emphasis on production of “commodities”. What is a commodity?

- Engels mentions a couple of examples of a “vicious circle” in the development of capitalism. What were they?

- What does Engels mean by the “rebellion of the productive forces”, and what are the “productive forces”?

- What is the fundamental reason that social forces are not understood or controlled by humanity? What needs to change in order for them to be understood and controlled?

- Which different relations between the State and the community does Engels mention as having arisen down the ages? What could it mean for the state to become “the real representative of the whole of society” and why would it then disappear?

Chapter 3: Production

The scientific view of socialism, which sees socialism as a necessary product of historical development, is a concept alien to Dühring. Engels sarcastically says he has it all worked out much better and his socialism is “a final and ultimate truth”.

Certain theoretical errors flow from this idealist approach. Like present-day reformists, Dühring cannot grasp the fundamental reason why capitalism periodically goes into crisis, i.e. overproduction. Instead he is stuck with the old notion of the underconsumption of the masses, which, as Engels points out, has been a constant feature in history for thousands of years and was a “necessary condition” in all class societies. It is precisely the new phenomenon of overproduction that sets capitalism apart from previous modes of production.

Engels then delves into one of Dühring’s preconceived schemas of economic communes, his “natural system of society”, but as with a lot of modern academic writings, we are left “to cudgel [our] brains as to what this means”. Instead Engels uses Dühring’s obscure and ambiguous writings to clarify his own position on one important aspect of how to organise a future communist society: the division of labour.

Whereas Dühring merely accepts the status quo of capitalism, Engels embraces the arguments of the utopian socialists, who wrote extensively on this question. In communist society, the “lifelong uniform mechanical repetition of one and the same operation” and “this stunting of man” would be done away with, but this requires a sufficient development of the productive forces.

Study questions and prompts:

- What exactly does Engels mean when he says “under-consumption of the masses is a necessary condition of all forms of society based on exploitation”?

- Are Marxists in favour of abolishing the division of labour? How does this tie in with Fordist production methods and automation?

- What does Engels mean by the “abolition of the antithesis between town and country” and how is this relevant to today’s ecological crisis?

- In what way does Engels depart from the arguments of the utopian socialists like Owen and Fourier and why does he introduce an element of “necessity” in this question?

Chapter 4: Distribution

Engels begins this chapter with a summary of Dühringian economics: “the capitalist mode of production is quite good, and can remain in existence, but the capitalist mode of distribution is of evil, and must disappear.” Dühring, like reformists today, is quite content to retain the capitalist mode of production and as a result doesn’t have much to say at all about how to organise production in his commune. As Engels says at the very end of the chapter, like Proudhon, Dühring “wants existing society, but without its abuses.”

Instead, the bulk of his theory is dedicated to distribution, which Engels likens to “social alchemizing”. Ironically, by ignoring the mode of production, or rather accepting the existing capitalist one, Dühring ends up setting up a scheme or plan for the future socialist society purely based on redistribution. That was not the method of Marx and Engels but of the utopian socialists.

In Dühring’s socialist system there would be trade between the “economic communes” (cooperatives) with pricing on the basis of estimates of the quantity of labour used. Inside the communes, each member would get a stipend and there would be an exchange of “equal labour for equal labour”.

Engels points out if you leave the capitalist mode of production untouched, this would lead to private hoarding and the “recreation of high finance”. Dühring ties himself in knots by ignoring the labour theory of value, which Engels addresses in this chapter whilst also elaborating the concepts of labour power and socially necessary labour time.

Study questions and prompts

- What are some of the flaws in Dühring’s understanding of capitalist economics?

- Engels describes trying to abolish the capitalist form of production by establishing “true value” as being “tantamount to attempting to abolish Catholicism by establishing the ‘true’ Pope.” What does he mean by this?

- What do Marxists think about cooperatives?

- What is the labour theory of value and why is it relevant here?

- Would the law of value apply in a socialist society? Did it apply in the Soviet Union? What about the production of commodities and surplus value in a transitional workers’ state?

Chapter 5: State, Family, Education

The final chapter shows an increasingly exasperated Engels grappling with some more of Dühring’s “detailed prescriptions” imposed on the future socialist society, in reality a “watery mess.” In Dühring’s society, there will still be an army and police force, but religious worship will have been abolished. Engels points out the absurdity of that decree, and the following couple of pages remain an excellent exposition of the materialist position on religion, which “is nothing but the fantastic reflection in men’s minds of those external forces which control their daily life, a reflection in which the terrestrial forces assume the form of supernatural forces.”

Just as Dühring “imagined that the capitalist mode of production could be replaced by the social without transforming production itself, so now he fancies that the modern bourgeois family can be torn from its whole economic foundations without changing its entire form.” In fact, the utopians were far ahead of Dühring and had valuable things to say about the transformation of private domestic work into a public industry, as well as the transformation of the education system.

At this point we should state that the working out of blueprints for the socialist society of the future formed no part of the materialist method of Marx and Engels, who were quite content to allow future generations to work out the details for themselves. But this does not at all signify that they left no idea about what socialism would look like, as Anti-Dühring itself proves. Marx and Engels traced the general lines in other works as well, such as The Critique of the Gotha Programme, Capital, The Civil War in France, and The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Lenin later developed these ideas in his writings on the state, especially State and Revolution.

However, unlike the utopian socialists or philistines like Dühring, Marx and Engels did not invent schemes for the future society, but always attempted to derive their ideas about socialism from the real historical conditions and the real movement of the working class. There are elements of the future socialist society already present in capitalism, just as the elements of capitalism were already coming into existence in the later stages of feudalism. Workers’ power and socialism are not invented by utopians or in the study of university professors or in Internet chat rooms but arise from the class struggle and the concrete historical experience of the proletariat.

Moving back to this final chapter of the book, Dühring also has his own fully worked out “prescription” and even curriculum for education, but again introduces absurdities such as banning the teaching of ancient languages, which Engels as a skilled polyglot understood to be fundamental to the understanding of the grammar of modern Indo-European languages.

Engels counterposes some of Dühring’s “spineless and meaningless ranting” to the clarity of Marx’ writing in Capital, in which Marx develops the thesis that:

“from the Factory system budded, as Robert Owen has shown us in detail, the germ of the education of the future, an education that will, in the case of every child over a given age, combine productive labour with instruction and gymnastics, not only as one of the methods of adding to the efficiency of production, but as the only method of producing fully developed human beings”.

At this point, the reader can sense Engels’ frustration during the writing of this classic of Marxism, and at the very end of the book bluntly states his verdict against Herr Dühring in the words: mental incompetence due to megalomania.

We for one, as socialist revolutionaries in the 21st century, are grateful to Engels for leaving behind this treasure trove of Marxist theory.

Study questions and prompts

- What does Engels mean when talking about the “natural death” of religion?