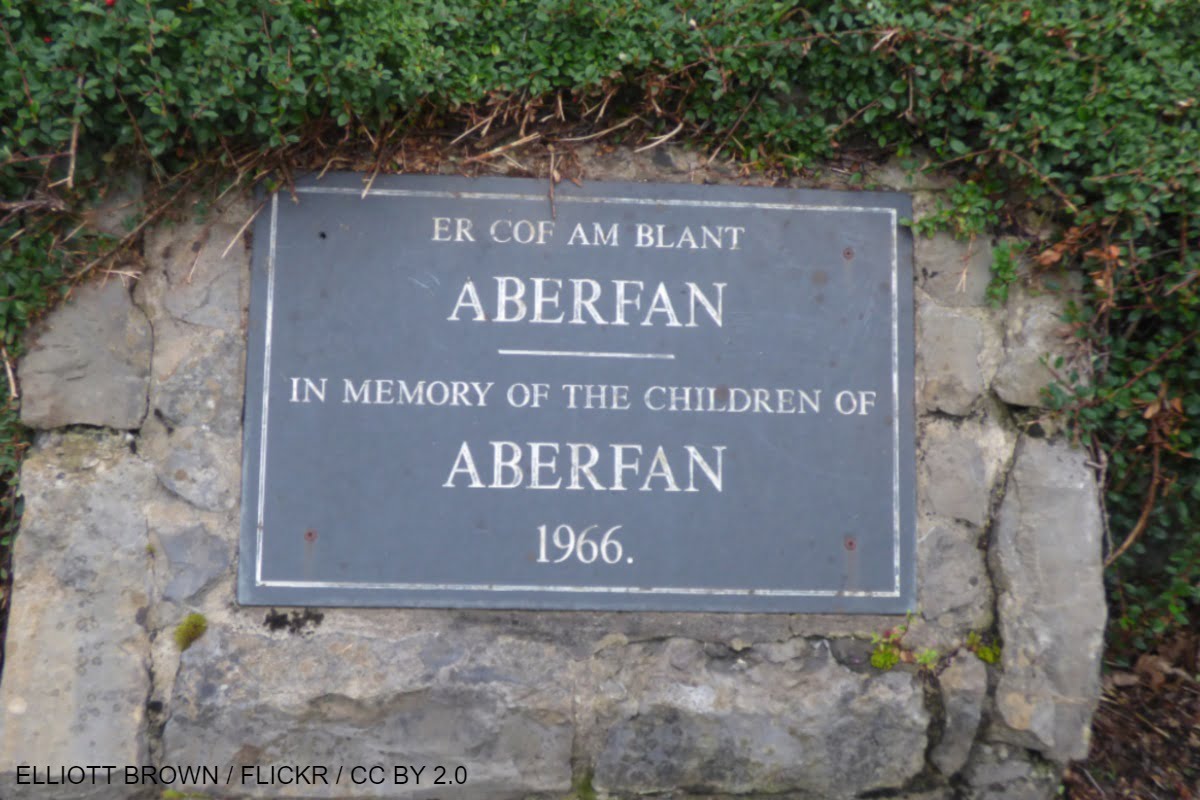

On this day in 1966, 144 people – including 116 children – were buried alive under 40,000 cubic meters of coal waste, which hurtled down a hillside at 80 miles per hour in a “glistening black avalanche”.

The slurry collided with Pantglas Junior School and several houses in the small Welsh village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil, at 9:13 in the morning. The last survivor was pulled from the rubble at just after 11:00 – an eight-year-old boy.

This avertible disaster, recently depicted by Netflix’s popular series, The Crown, was a direct consequence of the criminal negligence of the National Coal Board, and ultimately the British capitalist establishment.

A disaster waiting to happen

Aberfan is a mining village, and its 5,000 residents were well-acquainted with the dangers of both the profession and its byproducts. In particular, a series of vast spoil tips, consisting of two million cubic meters of waste material, loomed ominously over the village.

Aberfan is a mining village, and its 5,000 residents were well-acquainted with the dangers of both the profession and its byproducts. In particular, a series of vast spoil tips, consisting of two million cubic meters of waste material, loomed ominously over the village.

The valley in which Aberfan is situated experiences high rainfall. Coupled with the boggy ground, this meant that the tips were inherently unstable.

This was not helped by exceptional levels of flooding in the years leading up to the disaster, with residents repeatedly complaining to the Merthyr borough council that black, filthy flood water was seeping out of the tips.

Tip seven had already undergone two shifts in 1963. The National Coal Board (NCB), a government body responsible for coal mining, nevertheless continued to pile spoil onto the tip.

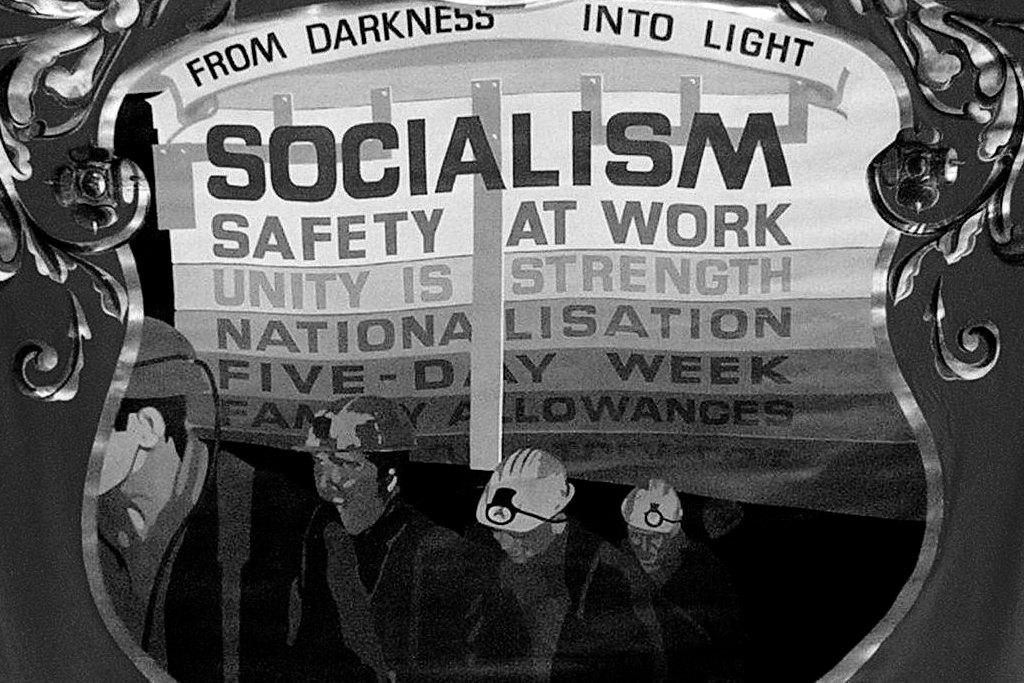

The NCB was created following the nationalisation of the coal mining industry in 1947. This was a step forward compared to private management by the capitalist coal magnates. However, the bureaucrats running the NCB were subservient to the bosses whose boardrooms they shared.

When coal mining declined in the 1960s, rather than investing in upgrading the sector, the NCB simply passed these losses onto the working class through dozens of pit closures – upending mining communities all over the country to protect the capitalists’ profits.

On multiple occasions between 1963 and 1964, warnings from Aberfan residents about the spoil tips were conveyed to the NCB via the borough council.

In a letter headed, “Danger from Coal Slurry being tipped at the rear of the Pantglas Schools”, DCW Jones, the council’s Borough and Waterworks Engineer, wrote:

“I regard it as extremely serious as the slurry is so fluid and the gradient so steep that it could not possibly stay in position in the winter time or during periods of heavy rain.”

In a second letter, he added that residents “have previously experienced…the movement of the slurry to the danger and detriment of people and property adjoining the site of the tips.”

Threats of closure

Local officials of the National Union of Mineworkers also raised the concerns of residents to managers at meetings of the Colliery Joint Consultative Committee.

A letter in reply from NCB’s Area Chief Mechanical Engineer acknowledged the risk:

“As you will appreciate, these tailings are very difficult to handle and we are very careful in disposing of this material, so as not to inconvenience any person or persons and, therefore, we would not like to continue beyond the next 6/8 weeks in tipping it on the mountain side where it is likely to be a source of danger to Pantglas School.” [our emphasis]

Instead of acting on these concerns and spending the money to remove the tip, the NCB allegedly threatened that any further fuss would see the mine closed altogether, effectively cutting the entire village off from its livelihood.

This was proved by the later testimony of S.O. Davies, Aberfan MP for Labour – to the shame of the party, which also led the central government under Prime Minister Harold Wilson.

Davies stated that he had long held concerns that the tip “might not only slide, but in sliding might reach the village”. He had not spoken out because he had “more than a shrewd suspicion that that colliery would be closed”.

In 1965, local people finally secured a series of meetings with representatives of the NCB, who promised to clear out the clogged pipes and drainage ditches around the tips. But by 1966, nothing had been done. The consequences were both tragic and inevitable.

Tragedy strikes

At 7:30am on 21 October, tip seven finally gave way. Workers assigned to the tip described a 30-foot-tall “tsunami of sludge” racing down the hillside and slamming into Pantglas School, immediately burying those inside.

The eight-year-old Jeff Edwards, who was pulled alive from the wreckage, later described struggling to breathe under the ocean of slurry as the screams and cries of his classmates “got quieter and quieter… buried and running out of air”.

There are tremendous stories of heroism amidst this tragedy. A dinner lady named Nansi Williams saved five students at the cost of her own life, shielding them from the landslide with her own body.

An army of workers and volunteers helped dig out survivors – and then bodies, after hopes of finding anyone living had faded. My partner’s relatives were among their number.

Having started at 9:30 in the morning of 21 October, a letter from a reporter described the men of the town still at work the following day, “with shirts off and bodies sweating despite the cold”.

The age of victims ranged from three months to 82. Of the 116 students, most were between the ages of seven and 11.

Empty gestures

The Crown depicts Queen Elizabeth declining to visit Aberfan until eight days after the disaster “out of respect” for the victims.

The Crown depicts Queen Elizabeth declining to visit Aberfan until eight days after the disaster “out of respect” for the victims.

In truth, this appearance came under pressure from the outpouring of public sympathy and rage for Aberfan, and was rightly regarded as a belated, empty gesture by an aloof establishment, following an avoidable tragedy in a working-class community.

A tribunal found the NCB solely at fault for the disaster, despite its chairman, Lord Robens (who kept his job), denying all wrongdoing. The borough council and NUM were not apportioned any responsibility.

The HM Inspectorate of Mines was also spared any direct blame, although it was found to have “failed in its duty”.

In the end, nobody at the top of the big coal bodies faced any punitive measures whatsoever, with the report concluding it was punishment enough “to be named by a tribunal of this sort”.

This is what justice looks like for the privileged bureaucrats and state officials responsible for the death of nearly 150 people!

In a final insult, the cost of removing the town’s remaining tips was paid out of a memorial fund of £1,750,000 (equivalent to £20 million today).

Relatives were then offered a ‘generous’ handout of £500 each from this fund – although the commission responsible originally intended to give them £50! This was all the compensation they would receive for the loss of their loved ones.

Never again

The callous capitalist system, along with the politicians and state bureaucrats at its beck and call, have repeatedly ignored dire warnings and allowed working class people to die rather than risk their profits.

The callous capitalist system, along with the politicians and state bureaucrats at its beck and call, have repeatedly ignored dire warnings and allowed working class people to die rather than risk their profits.

The arrogant elite act with impunity, safe in the knowledge that their near-sighted incompetence will seldom be punished.

We have seen this time again: from Aberfan, to Hillsborough, to Grenfell, to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Just this week, despite a new wave of cases, the Tories are refusing to take even basic safety precautions, with Health Secretary Sajid Javid passing off 1,000 deaths a week as “mercifully low”.

The victims of these acts of social murder will never see true justice under this rotten system.

The labour movement must organise and fight to put an end to capitalism: the only way to ensure that horrors such as the Aberfan disaster are banished forever to the dark past of human history.