The last few years have seen a number of Hollywood film companies marking their centenary anniversaries. Marxists see film, as with other art forms, as providing a reflection of class society and its structures. Bob Stothard looks over the long history of film and what it can tell us.

The last few years have seen a number of Hollywood film companies marking their centenary anniversaries. Of course, given the financial twists and turns within the film industry, many companies have not made it to the 100 year mark, or exist only as brand-names with very little in the way of actual film production taking place. Once-great companies like United Artists and MGM have suffered this ignoble fate with others like Orion and Avco-Embassy having gone for good. Nevertheless, we can see how cinema has survived and developed as a dominant art form both throughout the twentieth century and into the current one. Although the overwhelming majority of the films produced throughout the century could easily be described as trash (as, to be truthful, is the case with most other forms of media) there has been a layer of important and enduring films produced which are worthy of study. Marxists see film, as with other art forms, as providing a reflection of class society and its structures. Even popular exploitation films have something to tell us.

In this article, Bob Stothard looks over the long history of film and what it can tell us.

Rapid development

The initial development at the start of the 20th century of the film or motion picture industry was rapid. From Eadweard Muybridge’s sequence of a galloping horse in 1888, within a couple of decades the first studios and cinematographs would be established throughout the developed world.

In post-revolutionary Russia, Sergei Eisenstein made Battleship Potemkin (1925) in which montage unified the whole production. Eisenstein had earlier made the innovative leap of moving the camera to follow a subject. Prior to this, scenes were often enacted very much as stage plays with the camera as a static observer.

Eisenstein was revolutionary not only in film but also in political life. He eagerly supported the October Revolution and joined the military to further the aims of the Bolsheviks. Lenin and Trotsky quickly realised the powerful medium of film offered the revolution the opportunity to be observed and explained in the far-flung districts of the new Soviet Union. As internationalists they hoped also to spread the message to other countries.

In 1927 the first films with sound – ‘talkies’ – appeared along with Disney sound animations.

Many countries now had budding film industries, notably the French and Italians, but it was the USA where it burgeoned most quickly. California, with its reliable warm weather, long coastline, verdant rural interior, mountains and desert provided everything the film producers needed, nearby and at low cost.

In the difficult years of recession after the Wall Street crash young people set out west in the hope of finding fame and, maybe, fortune but, most pressingly, work of any kind.

Cinema attendances rocketed as the public sought light relief in escapist movies from the daily horrors of the recession and rampant unemployment.

Capitalists had quickly seen the money to be had in film. Huge studios were built and actors hired who were groomed into ‘stars’ – usually tied into sole-use contracts, restricting their abilities to work for competing companies.

Amongst the early subject staples were costume dramas, comedies, gangster and western themes or genres. With an eye on what was happening on the political stage the gunfighter or gangster was portrayed as a hero against the prevailing power – the individual who was unafraid of the Establishment; the entrepreneur against collective thought and ‘creeping socialism’.

Cinematic devices were – and still are – widely used. The tilt of the camera looks up to the hero, the good guy wears a white hat, an image in a mirror hints at ill-fortune and an animal, a dog or a horse for example, will always bark or whinny.

Social realism

Unlike France and Italy, the US industry largely steered clear of social realism. Some films made huge profits – mostly fantasies and costume dramas. But the odd realist movie which slipped through was heavily censored via the Hays Code (1930-68) established after some 37 states had enacted individual film censorship bills. This code exercised ‘moral’ and political guidelines for studios to follow or face the consequences.

The Supreme Court had decreed in 1915 that the hallowed Free Speech enshrined in the Constitution did not apply to films. The code laid down thirty-six possible transgressions which included miscegenation, use of the words ‘God’ ‘Jesus’ ‘damn’ and others, married couples not to be shown in bed unless both were in nightclothes and the husband had one foot on the floor!

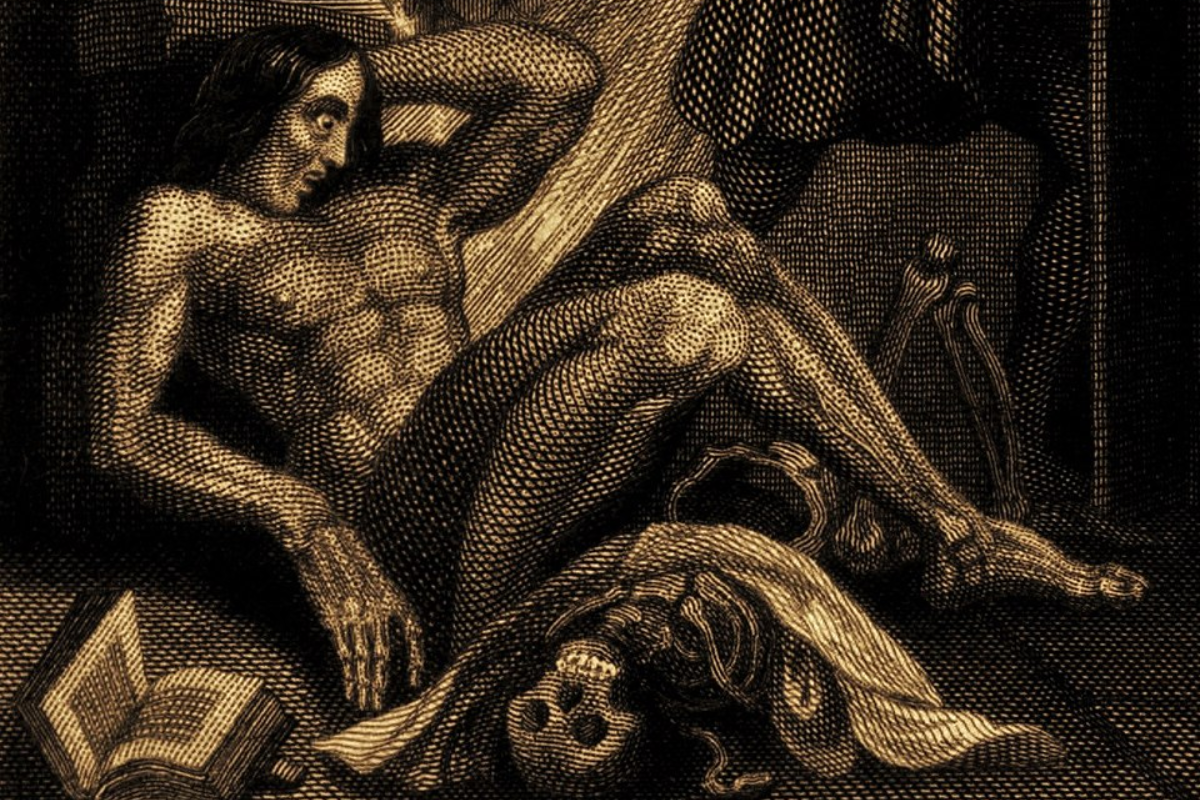

Perhaps the best-known crime of The Hays Code is the butchering of John Ford’s 1940 adaptation of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. The title comes from the Battle Hymn of the Republic. The second half of the film bears little resemblance to the book in that the family is never seen working on the farms – indeed, not a peach is seen throughout – and they end up not in a ‘jungle’ camp but a government-run facility with plentiful food, education and health care. Steinbeck’s stark, poignant ending, a woman having given birth to a stillborn child, offers her full breast to a man dying in a ‘jungle’ shack, was deemed unacceptable.

In Germany, the Nazis had seized the propaganda opportunities offered by film. Leni Riefenstahl, a popular actress, directed Triumph of the Will about the Nuremburg rallies. Fritz Hippler then directed The Eternal Jew infamously cutting between scenes of scurrying rats and Jewish life. It also featured Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein as Jewish ‘traitors’. The Americans and British responded with their own anti-Nazi propaganda during the war years.

Fear of Communism played a big part in Hollywood for the thirty years covering 1940 to 1970, particularly during the Korean War and the long Cold War. Countless gung-ho films – usually featuring John Wayne against the whole of China – and spy films showcasing unscrupulous Russians faced down by macho Americans or suave James Bond types were standard fare in cinemas. In between, beautifully produced but schmaltzy musical productions fought for air alongside religious ‘epics’ which had the curious side benefit of allowing much more female flesh on show – after all, who could complain when it was in the Bible? The Cecil B. DeMille epic “The Sign of the Cross” (1932) had been attacked by the Catholic Church for showing excessive violence, nudity and even hints of lesbianism yet thirty years later Cleopatra (1963) copied many of the same scenes including Elizabeth Taylor repeating the famous Claudette Colbert bathing shot

The one area where sexual allusion was permitted – indeed, encouraged – was the portrayal of black males. At a time when racism was enshrined in the statutes of many states the fear of rape by Afro-American men of white women was widespread. Consequently film portrayals frequently, shamelessly, cast such men as opportunist ravishers of defenceless white females – the stalking phallus.

Hollywood was not without directors, writers and actors who spoke out against McCarthyism, authoritarianism and for social justice. Many careers and job prospects were ruined by a witch hunt fronted by that paragon of towering intellect Ronald Reagan.

It is, in passing, strange that a country which pays so much lip service to God, the Bible and Creationism is also the world’s biggest legal producer of pornography. Nine tenths of this particular commodity is produced in the US, although Russia is trying to catch-up and Japan has long had its own peculiar variation of this. Porn, in fact, has been around since film technology appeared. It is cheap to produce and sales (or downloads) continue to boom. For the entrepreneur producers nothing is too sordid if there is an easy dollar to be had including trafficked women, children and animals

In the US and the UK ‘mainstream’ film caters for narrow interests. In Britain, productions concerning the urban middle class (Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Bridget Jones’ Diary et al) take plaudits from middle class film reviewers. In the USA however, reflecting that country’s apparent obsession with war and violence, military themed movies predominate. Even the gangster genre frequently features villains from abroad, usually Russia, who are even more ruthless than the home grown variety.

The working class in film

A cursory look at the subject matter of other types of US mainstream film shows a fanatical obsession with leading characters who are already wealthy professionals. When was the last time you saw an American film featuring working class (Americans don’t like to admit ‘class’ exists – they prefer ‘blue collar’) characters? In many senses the producers feel duty bound to protect the idea of the fabled American Dream – anyone can strike it rich if they work at it and those that can’t are somehow unworthy, unintelligent or lazy. In short, they are not suitable subject matter.

Michael D Higgins, President of Ireland and a former Irish Minister of Art and Culture, observed, “It is quite wrong that all the images of the world should come from one place.”

There was – indeed, still is – a belief within the British industry that to add an American actor to the cast would add ‘glamour’ and make the production more attractive to US audiences. The fact that said actors were not only often poor at their chosen profession but almost unknown in their native land seems to have been overlooked.

Who in Britain would argue Ken Loach’s films are uninteresting? Loach knows many of the best tales are within the lives of ordinary people – bus drivers, labourers, care workers and so on.

Yet, in the 1960s Britain produced a series of fine films, dubbed ‘kitchen sink’, based on a literary phenomenon known as ‘The Angry Young Men’. In A Taste of Honey, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Room at the Top issues of class and the everyday life of the working class were dealt with – not always to the liking of socialists it has to be said. Morality, humour, companionship and a desire for justice and fairness are to be found in spades within working class communities and households.

Independents

US actor and director Robert Redford has attempted to buck the US trend by encouraging independent filmmakers at his Utah Sundance festival. Rest assured, there are dissenting voices in the US film world as, like Loach, there are in Britain. Big distributors will not touch them and so they are doomed not to wider public acclaim but small independent – or ‘art house’ – cinemas.

The late John Cassavetes, an American innovative ‘naturalist’ film maker, suffered this fate despite critical praise being given for many of his titles, a number of which are now being re-issued on DVD.

Lousy US mainstream productions suffer the indignity of going straight to DVD or Netfix. In this latter category one can safely shove any film starring Jean Claude van Damme or Steven Seagal who, to judge by Channel Five’s listings, must make a movie every single week.

Compare, then, the recent offerings emanating from Europe – France and Italy in particular. Subject matter is considerably more realistic, supported by exemplary acting and directing. Add to this the terrific output from Japan, Russia and Korea. India has the world’s largest film industry (and audience) followed by China but both pursue a highly stylised output.

Whilst having followers in other countries, Indian and Chinese films are made chiefly for the huge domestic market because, when all is weighed up, the main objective is to make money. Add to this the fact that film audiences in the West, generally, do not like sub-titles, and dubbing (the norm for non-English films at one point) has largely fallen out of favour.

Yet again, as another capitalist crisis lurches along, those hardest hit seek escapist fantasy in film, whether at the cinema or at home taking brief respite from their troubled and care-worn lives.

Film is a branch of the arts and as such should be the property of the people. Art, in all its guises and forms is at present the purloined property of the bourgeoisie. Moving about in the social whirl that is the intelligentsia is as important to them as changing their shirts – and, ultimately – just as meaningful. There is kudos and money to be had and these come first.

A socialist society would make every effort to return the arts to its rightful and meaningful place at the heart of everyday life where it would flourish amongst a people freed from unemployment, want and fear.