Fifty years ago, on 11 September 1973, the coup d’état against Salvador Allende’s socialist government took place in Chile.

Allende’s election was the first time in history that a candidate who identified as a Marxist came to power through the electoral route. This fostered great illusions amongst social democrats around the world.

As president, however, Allende failed to carry the revolution through to its conclusion. The ensuing counterrevolution was relentless. The cost was paid by millions of Chilean workers.

In this article, we remember this painful milestone, and collect valuable lessons for the future of the class struggle.

On the morning of 11 September, 50 years ago, the inhabitants of Santiago awoke to the roar of warplanes over their heads. In the last radio station to be silenced, President Allende’s voice could be heard addressing his countrymen:

“My words have no bitterness, but disappointment, and they will be the moral punishment for those who have betrayed the oath they made (…). Given these facts, the only thing left for me is to say to workers: I am not going to resign! Placed in a historic transition, I will pay with my life for the people’s loyalty.”

Not only were the radio stations bombed, but also the President’s house and the government’s palace, in a grotesque scene that would be burnt into the memories of socialists around the world. After a symbolic resistance, Allende took his own life.

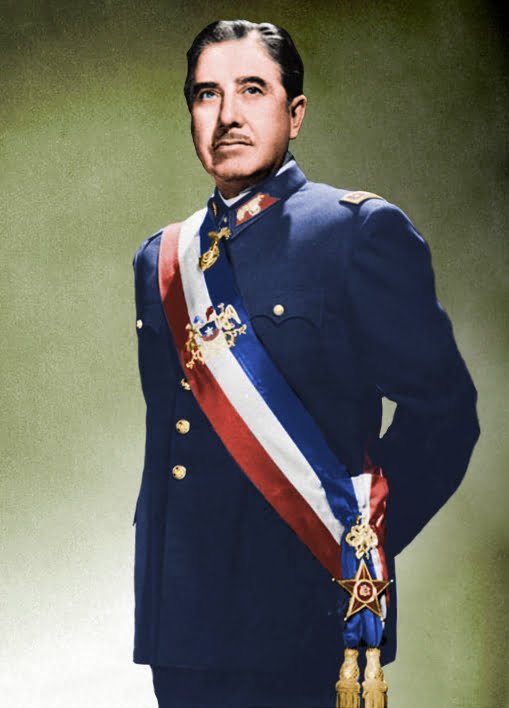

From that same day began a carnage against the Chilean working class, which would last for 17 horrific years. The dictatorship led by General Augusto Pinochet left a trail of death, disappearances and torture.

In a small country of 10 million people, official figures indicate that at least 27,000 people were tortured, 2,300 executed, and 200,000 exiled. The flower of youth and the working class was annihilated.

‘People’s government’

Salvador Allende was the leader of a coalition called Popular Unity (Unidad Popular – UP). The UP was formed in 1969 as a popular front, an alliance between petty-bourgeois parties and mass workers’ parties – in this case the Communist Party and the Socialist Party.

Salvador Allende, a Socialist Party parliamentarian, finally won the elections on September 4, 1970, with 37% of the votes, while the right obtained 35% and the Christian Democracy (DC) 28%.

The split of the conservative vote between the right wing and the DC candidates allowed the UP to obtain a majority. But the triumph was above all an expression of an increasing radicalisation of the masses during the sixties.

The UP strategy proposed a gradual and institutional transition to socialism. Its manifesto included a series of radical reforms in favour of the oppressed masses.

These included: the participation of workers in some areas of the state apparatus; national planning at the centre of a mixed economic model; nationalisation of the natural resources, the financial system and strategic industries; and state control over foreign trade.

Social programmes were launched in areas such as housing, social security, medical care, and education. Crucially, the manifesto planned to accelerate the agrarian reform, with expropriated lands to be cooperatively organised.

This programme, although reformist, was too far-reaching to be compatible with the interests of US imperialism and the local capitalists. As Lenin explained, moribund classes never relinquish power voluntarily.

Conspiracy

Once in government, the UP implemented its programme of democratic and anti-imperialist reforms. These included measures that directly affected US interests, such as the nationalisation of the copper mines, banks, and strategic companies.

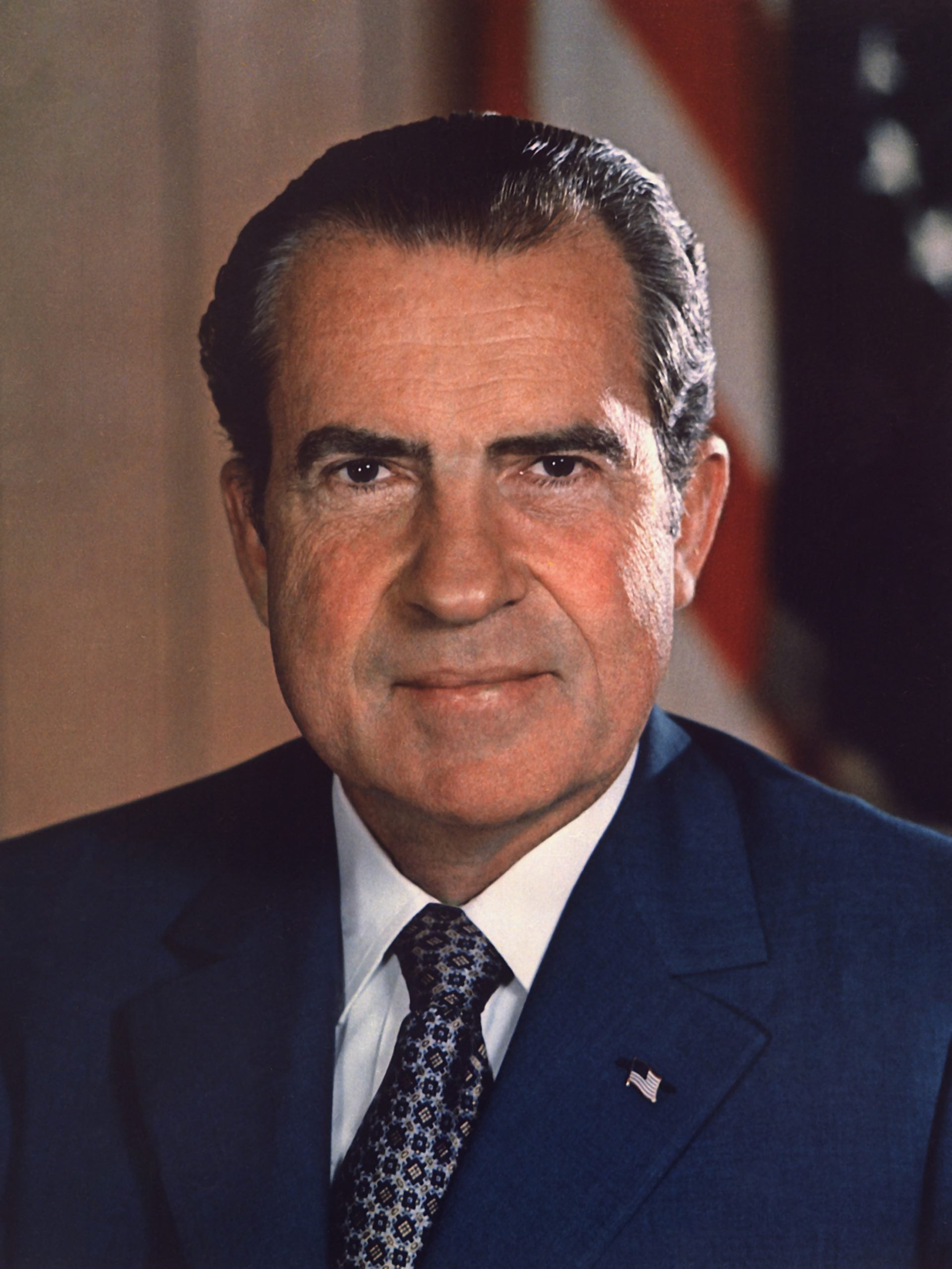

This triggered the fury of President Nixon, who declared that it was necessary to “make the Chilean economy scream”. The imperialist boycott meant the seizure of financial assets and cargoes of Chilean copper abroad, as well as blocking access to loans, machinery and spare parts.

All this contributed decisively to the deterioration of the social and economic situation. But surreptitiously, imperialism also intervened through the CIA, devoting more than $13 million to right-wing parties, opposition media and employer’s associations. This led to three years of economic sabotage, parliamentary blockade, propaganda campaigns, and terrorism.

During the first months of government, a ‘Social Property Area’ was created, with the participation of workers, comprising 90 nationalised strategic companies. Workers took this initiative much further through factory occupations, taking the total to 254 companies in the Social Area.

Until mid-1972, in some nationalised companies production doubled, which went hand-in-hand with a growth in the consumption of national products, a sign of a better quality of life for workers.

The agrarian reform expropriated 5.3 million hectares of basic irrigation land from rich landlords, reaching up to 35% of agricultural land. All this was reflected in an increase in electoral support for the UP parties in the 1971 municipal elections, reaching 50%.

The nationalisation measures carried out by the Allende government, however, were half-hearted, shying away from replacing the anarchy of the market with democratic planning. Once the bourgeoisie’s institutional maneuvers failed, they took advantage of this situation by using the control it still maintained over the economy to sabotage the government.

The bourgeoisie and imperialism were aware of the sharpening of the class struggle. The working class was threatening to outstrip the limits of bourgeois democracy, despite attempts at containment by the leadership.

The factory owners therefore called for a lockout. The owners of trucks carried out a ‘strike’ that affected the transport of fuels, raw materials, food, and maritime loads. They were joined by a reactionary strike of public transport and some mining sectors, along with mobilisations of students from private universities and petit-bourgeois professional sectors.

Workers’ organisation

The working class responded to these provocations in a formidable display of conscious mobilisation in defence of its class interests. They established democratic grassroots organisations, such as the Supply and Price Boards, which organised the distribution of basic products, and fought the bourgeoisie’s tactic of hoarding and the black market.

The peasant committees protected the recovered land from the armed bands of landowners. To combat the lockout, the committees in defence of industrial production occupied the factories abandoned by the bosses, controlled production, and manufactured their own spare parts, with the strategic support of the committees of housewives.

In district areas, these organisations combined into the ‘Cordones Industriales’ (Industrial Belts) which mobilized between twenty and thirty thousand workers in Santiago.

As in all revolutions, an embryo of dual power was thus established, which went beyond the factories, and which managed to organise peasants and working class communities. A revolution ‘from below’ began to overtake the revolution ‘from above’ of the government and the unions.

The Chilean workers showed in a rudimentary way how the working class can direct production and society on a new basis. But this drive towards the seizure of power was thwarted on every important occasion by the leaders of the Communist Party and the socialist President Allende.

After a month, the bosses’ lockout was defeated. Allende’s response was not to arrest or expropriate those bosses, but to form a new cabinet involving the military. This was an attempt to placate the capitalist class by making the military tops part of the government. But it was a slap in the face of the workers, since they had already defeated the bosses and had no reason to placate them.

A gun control law was also enacted, which was used in raids against the Cordones Industriales, taking weapons off the workers’ organisations. Yet in the months before the coup, it was the fascist gangs that carried out up to twenty attacks daily, and they were barely touched.

As a left reformist, Allende believed in the democratic character of the state, hence there was no need for workers to be armed: the military would protect the government voted in by workers. The same belief meant he saw no need to ‘provoke’ the fascists by disarming them, since once again the military would defend the government against them.

Dress rehearsal

The UP obtained 44% of the votes in the parliamentary elections of March 1973. The right failed to weaken the government in the electoral field. But the advanced workers were conscious that a coup conspiracy was imminent. The question then was whether to wait for aggression or to take the initiative.

On 29 June 1973, mid-level army officers organised a revolt against the government. The loyal commander-in-chief, General Prats, accompanied by a certain General Pinochet, repressed the insurgents in the centre of Santiago (Prats would later end up killed in exile on Pinochet’s orders).

The Cordones Industriales took the initiative and occupied all the factories in the capital and the main accesses to Santiago, and the peasants centralised the supply of food. The dress rehearsal for the coup was defeated.

This would have been an enormously favorable moment for Allende to lean on the working class and launch an offensive to expropriate the capitalist class as a whole. He should have said to the workers: “occupy the factories, and we will nationalise them”. There is no doubt that the workers would have done so, capitalism in Chile would have been finished, and the working class would have held power.

Instead, Allende asked the workers to stop the occupation of factories, allowing the capitalist saboteurs to retake them. The very government the workers were using revolutionary means to defend was betraying the workers.

Still, on 4 September, 800,000 workers marched in front of the presidential palace, asking for weapons to defend against the right-wing military conspiracy, and the closing of the congress. On 5 September, the Cordones Industriales sent a letter to President Allende with a clear warning:

“We are absolutely convinced that historically the reformism that is sought through dialogue with those who have betrayed us time and time again, is the fastest path to fascism.”

Coup

Allende and the leaders of the UP, however, remained stubbornly attached to their conception of a ‘democratic’ state that obeyed the government and a ‘constitutionalist’ armed forces that respected the chain of command.

Ignoring the clamour of the working class, Allende proposed to the parties a plebiscite, in an attempt to use parliamentary methods to resolve the class struggle. The date of the coup d’état was set by the senior military commanders for 11 September, to prevent the announcement of this measure.

That day, workers concentrated themselves in the workplaces, waiting for instructions. But none were forthcoming.

Naturally, the military of the bourgeois state always has enormous technical advantages over the working class. They have at their disposal vast armouries of killing machines. It is said that Allende’s mistake was not to arm the workers, which is true, but this misses the bigger problem, which is political and organisational.

Even if the workers were armed, the military would retain an advantage in weaponry. But its weapons always require soldiers to do the aiming and firing, and these soldiers are largely members of the working class and peasantry.

This is why the revolutionary party is indispensable. In the Russian Revolution, the Bolshevik Party recruited and developed cadres in the working class and in the military, and before taking power they used their cadres to win over swathes of the Tsarist military rank-and-file to the revolution. This made it impossible for the counter-revolution to stop the insurrection, which as a result was a bloodless affair.

Had the Chilean working class been organised and led by such a revolutionary party, it could have quickly won over and organised the forces used by Pinochet in his coup and prevented it from even taking place.

Instead, Allende relied upon the formal chain of command at the top of the military. But Pinochet consciously betrayed his government, and proved loyal to another chain of command: that of the ruling class and the US imperialists, who helped organise and fund his coup d’etat.

Whilst spontaneous resistance took place here and there, the confusion and lack of leadership meant that the military controlled the whole situation in a few hours.

Allende’s final speech summed up the impotence of his leadership:

“Workers of my country: I want to thank you for the loyalty that you always had, the confidence that you deposited in a man who was only an interpreter of great yearnings for justice, who gave his word that he would respect the Constitution and the law and did just that (…). The people must defend themselves, but they must not sacrifice themselves. The people must not let themselves be destroyed or razed, but they cannot be humiliated either (…).”

Dictatorship

The DC and moderate sectors of the bourgeoisie thought that the military would transfer power to them in the short term. But the dictatorship lasted 17 years. The masses were demoralised and powerless in the face of the triumphant reaction.

There was a disastrous economic situation, after years of sabotage by the right wing itself, but also a product of the international crisis of capitalism. Despite its internal contradictions, the dictatorship was able to maintain itself by inertia.

It was not until the arrival of economists educated at the liberal school of the University of Chicago, the ‘Chicago Boys’, that the regime adopted an economic and political project that was combined with local Catholic conservatism.

The dictatorship did not simply recover the lost positions of the bourgeoisie and imperialism, but transformed the social and economic structure of Chile into the notorious so-called ‘neoliberal’ model that would be exported around the world.

This included vicious anti-trade-union laws (that inspired Thatcher); the privatisation of copper, a key pillar of the economy; the privatisation of pensions, massive cuts to public education and the privatisation of university education, and many, many more.

But the economic liberalisation imposed by blood and fire did not have the effects that its creators supposed. In 1982, Chile suffered the biggest economic crisis since 1930. GDP fell 15%, and unemployment reached 40% in some areas.

Resistance

These factors explain the protests that took both the military and political parties by surprise. The demonstrations were massive and especially combative in the slums of Santiago, but trade unions and professionals also joined in.

The Communist Party, after a series of ups and downs, and influenced by the spirit of young militants inside the country, started to promote a mass rebellion. The largest national protests took place in 1986, with a general strike.

Faced with the growth of a pre-insurrectionary mood that threatened to overwhelm negotiations for the end of the dictatorship, the Communist Party formed the paramilitary organisation Patriotic Front Manuel Rodriguez (FPMR).

But the attempt to set up an armed organisation separate from the mass movement was a failure. Weapons sent from Cuba were seized, and a month later, an attack on Pinochet was foiled. These defeats plunged the Communist Party and the FPMR into a crisis.

The surviving social democratic leaders drew all the wrong conclusions from their catastrophic defeat in 1973, and like social democrats all over the world at this time, moved to the right. They abandoned any pretence of fighting for socialism. Their main idea was to come to an agreement with the military for the return of bourgeois democracy.

Transition

This idea produced the Concertación, the alliance between social democrats and Christian Democrats, which campaigned for a plebiscite in 1988. ‘Option No’, which implied the departure of Pinochet and a call for free elections, won with 56% of the votes.

The agreed democratic transition was a compromise from above, to avoid revolution from below. The official myth fed to Chileans today is that the dictatorship was defeated with pen and paper. Impunity for the crimes of the dictatorship was established and the armed forces remained untouched.

The Concertación administered the democratic aspirations of the Chilean people after the dictatorship. But they ruled keeping most of the legacy of the dictatorship intact, making the necessary superficial changes so that nothing changed. The same ‘neoliberal’ capitalist policies remained.

Ultimately, the coup took place not for the sake of having a dictatorship, but to protect capitalism from the revolutionary demands of the masses. Capitalism, and the economic policies of Pinochet, remained in place despite the removal of Pinochet himself from power.

Fifty years after the bloody coup d’état, Chileans still live with the legacy of that defeat. The uprising of 2019 represented a rejection of the entire regime created at the end of the dictatorship.

It is crucial to draw the necessary lessons from the Popular Unity government. The main one is understanding the class character of the bourgeois state, which cannot be used to gradually introduce socialism.