Fifty years ago today, British troops were sent into the North of Ireland, marking the start of the Troubles. Rob Sewell explains why only the fight for a Socialist United Ireland can bring an end to sectarianism.

At 5.15pm on 14 August 1969, British troops were sent onto the streets of Northern Ireland. They were to remain there in force for more than a quarter of a century. It marked the beginning of the ‘Troubles’, in which 3,500 people were to lose their lives and 50,000 were injured.

The Northern Ireland state had been brought into being in 1922 as a result of the division of the living body of Ireland by British imperialism. The creation of the six counties arose out of the fear that the revolutionary upheavals in Ireland in 1918-1920 would spread to Britain. The British ruling class also wanted to hold onto the industrial north, together with its important strategic ports.

The state of Northern Ireland was an artificial creation, based on a Protestant majority and with a Catholic minority that faced systematic discrimination and oppression. Stormont became “a Protestant Parliament for Protestant people”.

The Southern state, the so-called Free State, was in turn dominated by a semi-military government, resting on the domination of the Catholic church, where abortion and contraception were banned.

Despite all the talk, the unification of Ireland could not be brought about by the enfeebled Irish bourgeoisie, who were not interested in absorbing a disgruntled Protestant minority. The only class capable of solving the national question, as James Connolly explained, was the working class united in the struggle for a 32 county Workers’ Republic.

Sectarianism

The sectarian-based rule in the North was founded on gerrymandering and the fostering of sectarian hatred. The right to vote was denied to many as only ratepayers were enfranchised, meaning that, for example, slum landlords owning 100 properties had 100 votes. Catholics were deliberately kept out of power, while the parliament at Stormont and the local authorities were dominated by the Unionist Party.

There was widespread poverty, slum housing and unemployment in the North, especially amongst Catholics. They faced daily discrimation in jobs and housing. Emigration for the youth became a way of life. Working class Protestants also faced such problems but to a lesser extent.

The Unionist domination was backed up by the armed Royal Ulster Constabulary (the RUC) and reinforced by an auxiliary police force, the A, B and C-Specials. These were Protestant armed bodies defending a Protestant state.

However, by the 1950s and 1960s, the strategists of British capitalism had come to regard the border as an anachronism to free trade. By 1969, Britain was taking 70% of the South’s exports and providing 50% of its imports. They dominated Ireland economically and the North was becoming a drain on the British Exchequer.

An Anglo-Irish free trade agreement was therefore signed. The Irish prime minister Lemass met O’Neill, the Unionist prime minister, for talks about closer cooperation. The Unionist hardliners, led by the Reverend Ian Paisley, were outraged. They represented the face of open Protestant reaction. Sectarian clashes were whipped up to undermine the initiative.

The problem for the British ruling class was the very sectarian state that they created and which relied upon partition. They had created a Frankenstein’s monster over which they had little control.

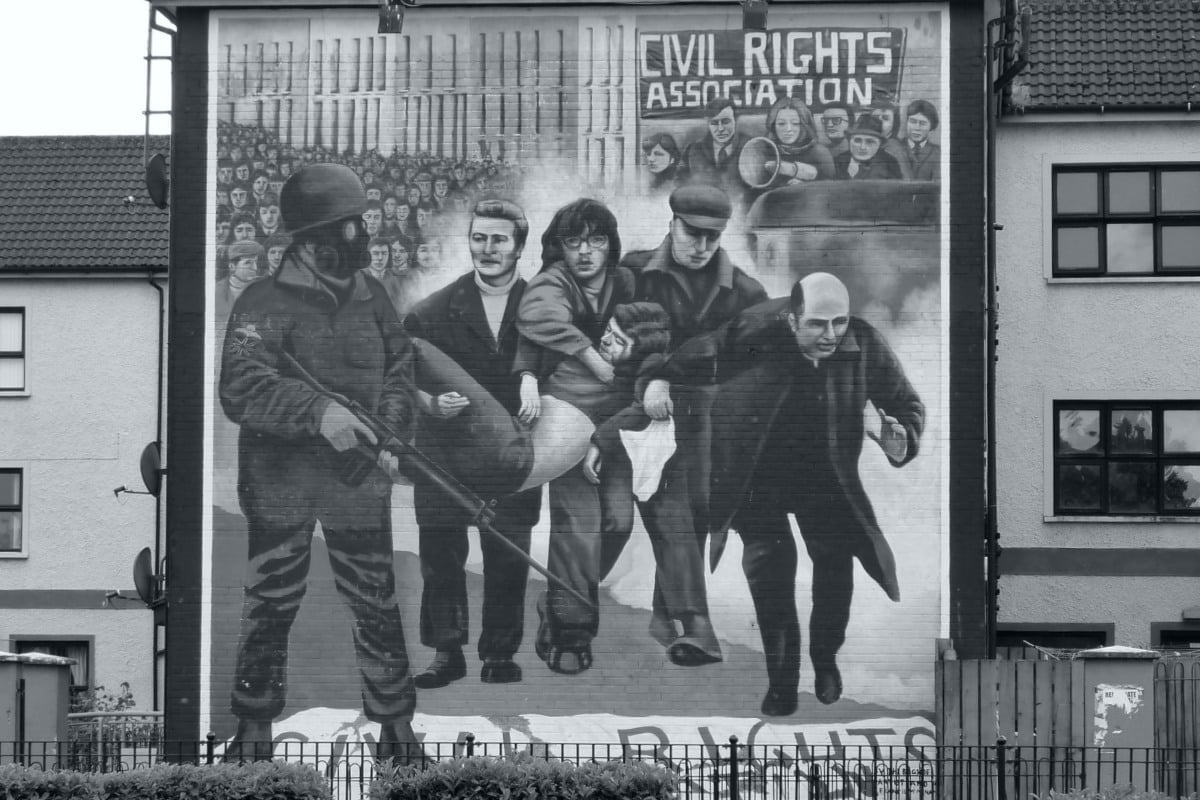

Civil rights

The 1960s was a period of universal international radicalisation and revolt against the old order. The French general strike in 1968 reverberated around the world. The civil rights movement in the United States also had a massive impact on the situation.

This turmoil provided the background to the formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), a broad alliance, in April 1967, which involved the Communist Party. This body became the focal point for the mass movement for civil rights in Northern Ireland. However, the CP adamantly refused to arm the movement with socialist demands, saying that it must confine itself to broad-based ‘democratic’ demands.

In Derry, however, the anger of the youth spilled over into direct action, especially focusing on the discrimation in housing. A demonstration was organised for 5 October 1968, which involved the Derry Young Socialists, with the slogans “working class, unite and fight” and “Orange and Green Tories out”.

Eamonn McCann, a leading left winger in the Derry Labour Party, who would later document much of what happened, played a key role. This was in marked contrast to the NICRA.

The demonstration was banned by the authorities, but the ban was defied. However, when they tried to march, they were set upon by the RUC, who savagely beat the protesters with their truncheons. But this only served to intensify the movement.

The scenes of police violence that appeared on TV screens opened the floodgates of discontent within the Catholic working class. There was a call for further marches and a strike.

The NICRA as usual called for restraint. This backsliding led to the vacuum being filled by a new body, the Citizens Action Committee (CAC), a middle class body, led by John Hume. He stated, “It was a movement without political aims. Civil rights is not a political issue. It is a moral issue.”

The civil rights movement could have united Catholics and Protestants, but this non-political approach undermined it. Only a socialist programme fighting poverty across the religious divide could achieve unity.

However, another organisation sprung up in Belfast’s Queen’s University called People’s Democracy (PD), which was far more radical than the NICRA or the CAC. They organised militant pickets, occupations and marches. Its leading figure was a young student, Bernadette Devlin. The PD was a left-wing socialist organisation, albeit without a clear programme. Groups of the PD sprung up everywhere, attracting a large layer of Catholic youth.

Whenever they organised marches, they were set upon and beaten up by hardline Paisleyites.

Rampage

Fearing the situation could get out of hand, a few concessions were promised by the Stormont government, which led to the CAC and the NICRA suspending its activities.However, after an interval, the PD stepped in to organise a march across the North.

On New Year’s Day 1969, about 80 people set out from Belfast. The march was continually taunted and blocked by Loyalists, supported by the RUC. The march eventually grew to 400. At one point, the marchers were ambushed, attacked and stoned, while the police just looked on. On their way to Derry, they were viciously attacked once again, including by the B-Specials. Bloodstained and battered they eventually reached Derry.

That night, the RUC went on a rampage in the Catholic Bogside area of Derry. This provoked a mass response. The people rose up and built barricades and so ‘Free Derry’ was born. The RUC were kept out of the area for a week.

On 17 April 1969, a by-election was held for the Mid-Ulster seat in Westminster. The 21-year-old civil rights campaigner, Bernadette Devlin, won the election on a 91.78% turnout with the biggest anti-Unionist majority since the seat was created.

“The only hope for the people is to unite against the system,” explained Bernadette. “I believe that Catholic and Protestant workers realise the necessity of standing together on a non-sectarian platform of radical policies.”

Loyalist reaction

The Paisleyites were busy stoking up sectarianism. Their constant refrain was “Ulster is Protestant and British”. Every civil rights march would produce a Loyalist counter-demonstration. Derry had become a battle ground. Every time the RUC would charge demonstrators, attempting to push them towards the Bogside. This provoked serious rioting, where youths used stones and petrol bombs to ward off the police. Over one weekend in April 1969, 165 people were admitted to hospital with serious injuries.

On one foray into the Bogside, the RUC had broken into a house where Samuel Devenney and his family lived. His daughter explained what happened:

“My father fell in backwards through the front door. The police appeared. My father fell on the floor. Seven or eight policemen came into the room. There were four policemen around and three of them were standing and hitting my daddy with their batons and kicking him. The fourth was kneeling and hitting him with his baton.” (Irish News, 16/12/69).

He was admitted to hospital with head injuries and died a few months later. He was the first victim of the ‘Troubles’.

In the same month, Loyalist reaction raised its head with the formation of the Shankill Defence Association, an extreme and virulent anti-Catholic outfit. Its aim was to make the Shankill one hundred percent Protestant, by means of threats and intimidation.

The CAC vanished, not wishing to take any responsibility. A new “Derry Citizens Defence Association” was formed to protect the area from attack by the Paisleyite gangs, the RUC and the B-Specials.

Days of battle

Everyone knew the crunch would come on 12 August, the day of the Apprentice Boys’ parade in Derry. It would be attended by thousands of Orangemen from all over the North, fuelled by sectarianism. The march was a calculated insult to the Derry Catholics. As resentment grew, the first barricades went up on the 11th in anticipation.

Everyone knew the crunch would come on 12 August, the day of the Apprentice Boys’ parade in Derry. It would be attended by thousands of Orangemen from all over the North, fuelled by sectarianism. The march was a calculated insult to the Derry Catholics. As resentment grew, the first barricades went up on the 11th in anticipation.

Feelings reached fever pitch. The march was stoned. This was the excuse the RUC wanted to intervene, supported by the Loyalists. The fighting was heading towards a pogrom. This provoked a mass uprising in the Bogside, with barricades being erected in streets to defend their homes.

“As the volume of stone-throwing increased a mixed force of RUC and supporters of the Apprentice Boys made a charge into the area, which was the signal for the hostilities to begin,” recalled Eamonn McCann later.

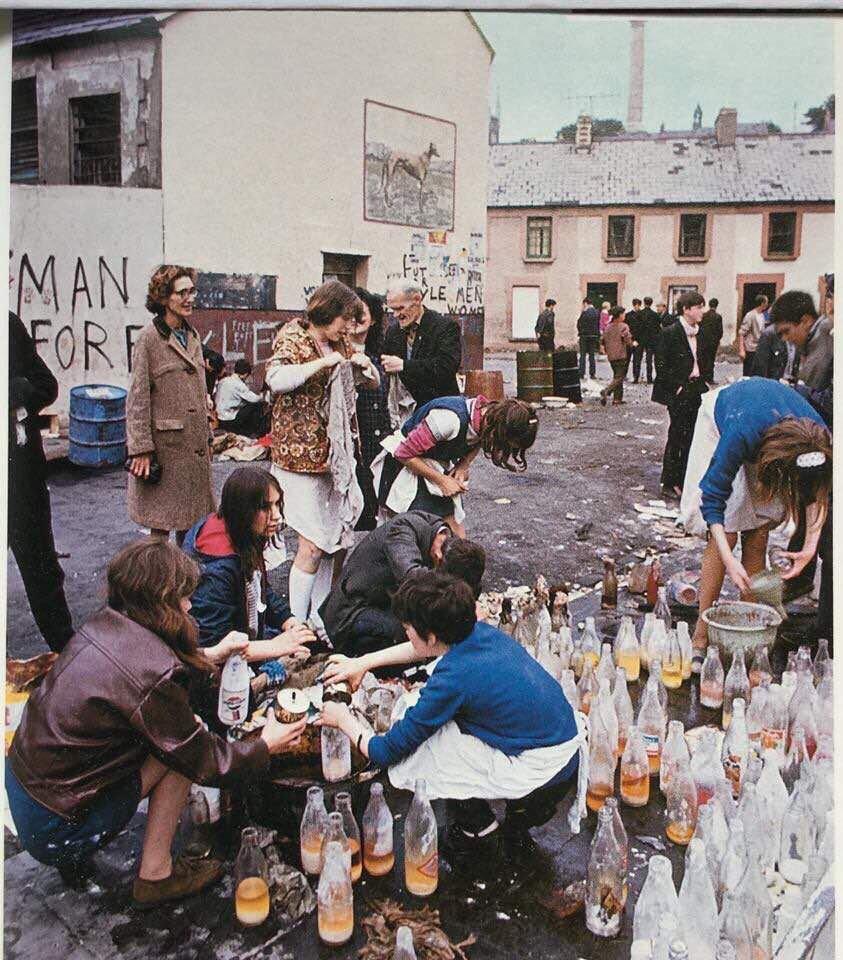

“The battle lasted for about forty-eight hours. Barricades went up all around the area, open-air petrol bomb factories were established, dumpers hijacked from a building site were used to carry stones to the front. Teenagers went on to the roof of the block of High Flats which dominates Rossville Street, the main entrance to the Bogside, and began lobbing petrol bombs at the police below.”

The police started using tear gas. Water and vinegar were rushed to the front as an antidote to the fumes. Phone calls were made to other areas to come to Derry’s assistance by drawing away the police.

In the main battle at the edge of the Bogside, the fighting was led by Bernerdette Devlin, who displayed particular heroism.

The ‘Battle of the Bogside’ lasted a few more days. There were reports of other disturbances in Belfast, Strabane, Dungiven, Omagh, Lurgan, Newry, Enniskillen and elsewhere. The RUC were being worn down. Out of a force of 3,200, six hundred officers had already been injured since the beginning of the civil rights protests. In the Bogside, the police were being pushed back and they were unable to contain the insurrection.

Paisley demanded the mobilisation of the B-Specials and a ‘people’s militia’ to crush the insurgence. By the 14 August, the B-Specials were being used and fears grew that live ammunition would be used to put down the Catholics.

This was the same day as the first duplicated edition of the Barricades Bulletin was put out by the Derry Labour Party, detailing how to handle petrol bombs and appealing against any vandalism or joyriding in the area. “The enemy is weakening. They have been on their feet for two nights. One more push” it said.

British soldiers on the streets

It was at this point, late in the afternoon, that the RUC and the B-Specials began to withdraw. In their place appeared armed British soldiers from the Prince of Wales Regiment.

It was at this point, late in the afternoon, that the RUC and the B-Specials began to withdraw. In their place appeared armed British soldiers from the Prince of Wales Regiment.

The Bogside regarded this as a defeat for the RUC. There was widespread relief. Bernadette Devlin urged that the troops should not be made welcome, but this was not the general feeling.

Within 24 hours, the army was asking for a meeting. A delegation from the Defence Committee put forward their demands, which included holding onto the area until the police were disarmed and the B-Specials, the Special Powers Act and Stormont were abolished. No soldier would be allowed through the barricades. The army was forced to bide its time and agreed not to enter.

Power in the Bogside resided with the Defence Committee, which had greatly expanded from an ad-hoc body to one representing the community. It was an embryo of workers’ power. It took all the decisions democratically at public meetings held every few days. “When the fighting ceased representatives of various groups – tenants’ associations, street committees and so on – were accepted as members,” explains McCann. It established its own ‘police force’ to deal with any problems. ‘Punishment’, more often than not, consisted of a stern lecture.

The left acted as a caucus within the Defence Committee, most of whom were in the Labour Party or the Republican Club. “For weeks we were fairly happy about the way things were going. Our public meetings were well attended and enthusiastic. Our bulletins were accepted and read eagerly. It appeared that our faction represented a considerable body of opinion, that we were a force to be reckoned with – and no longer trapped within a ‘moderate’ alliance,” explained McCann.

Barricades were also thrown up elsewhere, including in Belfast in the Falls Road and the Ardoyne, where there was rioting. 150 Catholic homes were burned in Belfast by Loyalist mobs. In fact, in July, August and September, 1,820 families fled their homes in Belfast, 82.7% were Catholic.

The Loyalists bigots felt embittered. They were outraged by the existence of “No-Go” areas behind the barricades, where the Crown’s forces were not allowed to operate.

Eventually, the barricades did come down, first in Belfast, then Derry, but the intimidation continued. However, there were attempts to curtail sectarianism. Defence committees, which had sprung up, worked to keep order.

At the Harland and Wolff shipyard a mass meeting approved a resolution unanimously “for the immediate restoration of peace throughout the community”. Loyalists however stepped up their efforts to sow sectarian disunity. The trade unions failed to counter this with the establishment of organised defence committees.

This failure to defend the Catholic areas led to the rise of the IRA. Given this vacuum, both the Official and the Provisional IRA grew substantially. The truce between the army and the Catholic community came to an abrupt end. Internment was introduced. A new phase opened up: the so-called ‘armed struggle’.

Deep divides

British troops had not been sent in to defend the Catholic minority, which was the main official reason given, but to ‘contain’ the situation. The army was sent to the North as agents of the British ruling class to protect their property and safeguard their interests. They were not going to play a neutral role, as many on the left believed, with the honourable exception of the Militant, which opposed troops being sent.

Among those who supported the intervention of British troops were the Socialist Workers Party, as well as the Labour left. Eventually, the interests of the British army and the interests of the Catholic minority would come into conflict. This became abundantly clear in the period that followed.

Derry Labour Party stood out against the general mood at the time. Its Barricade Bulletin explained:

“We were pleased to see the troops. They have behaved well. For this reason some people seem to think that the troops are here to protect us. They are not, any more than the RUC and the Specials. They are here to protect the interests of the British government in this part of the United Kingdom.”

Many of the youth who participated in the ‘Battle of the Bogside’ were drawn into the armed struggle, believing they were fighting for a socialist united Ireland. This whole generation was later betrayed as their ‘leaders’ swopped the gun for a nice ministerial post in a revamped Stormont, alongside Paisley and the DUP.

The sectarian divide is deeper today than ever before. The collapse of ‘power-sharing’ is a reflection of the impasse of capitalism in the North. The 25 years of the so-called ‘peace process’ has not resolved the problems facing the working class, despite all the money poured in by the European Union.

The only solution to these problems, North and South, is the overthrow of the capitalist system that breeds poverty, homelessness, unemployment and sectarianism. Only the unity of the working class, born out of the class struggle, as James Connolly explained, can offer the way forward. Only they can resolve the national question and eliminate the border. That means the fight for a Socialist United Ireland and a Socialist Federation of Britain and Ireland.