In the third and penultimate part of his series commemorating the life and ideas of the Bard, Alan Woods looks at the central role of politics, plots, and intrigues in Shakespeare’s plays, and – in particular – his attitude towards the idea of social revolution.

In the third and penultimate part of his series commemorating the life and ideas of the Bard, Alan Woods looks at the central role of politics, plots, and intrigues in Shakespeare’s plays, and – in particular – his attitude towards the idea of social revolution.

Shakespeare and politics

The age of Shakespeare was also the age of Machiavelli. That brilliant Italian philosopher was the man who first explained that the conquest and maintenance of political power has nothing to do with morality. The state itself is organised violence, and the seizure of state power can only be brought about by violent means. Moralists have given the Italian philosopher a very hard time, but history has shown that his analysis was basically sound.

In Shakespeare’s plays, particularly the history plays, we have an eloquent description in literature of what Machiavelli demonstrated in political philosophy. The history plays deal with the power struggles that culminated in what became known to us (incidentally thanks to Shakespeare) as the Wars of the Roses. The struggle for power (in this case, monarchical power) is achieved through intrigue, backstabbing, betrayal and murder.

This was a world in which violence and treachery were the normal tools of the trade in monarchical politics. The feudal system was breaking down and capitalism was beginning to take root. The old aristocracy was being undermined and physically annihilated by a long and bloody conflict. This senseless conflict between rival dynasties was characterised by extreme violence and thuggery in pursuit of power. Two gangs of robber barons slugged it out, while the kingmaker Warwick balanced between them. For thirty two years the nobles of England had slaughtered each other without mercy.

That bitter struggle for the English throne played an important role in undermining the feudal order in England. In the end both Houses – York and Lancaster – were exhausted. Edward IV (1461-1483), of the House of York, was succeeded by his brother Richard, made notorious by Shakespeare in his play Richard III. In this play Shakespeare describes how the Duke of Clarence was knifed and then drowned in a barrel of wine on the orders of his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later Richard III. Henry VI was murdered in prison, probably by Richard himself. These were typical of the charming methods used by the nobility of England in the Age of Chivalry.

This was an example of the “the brutal display of vigour in the Middle Ages” to which Marx refers in The Communist Manifesto. These murderous civil wars finally ended with the death of Richard III, the last Yorkist King, at Bosworth in 1485. The result was the rise of a new dynasty founded by the Welsh adventurer Henry Tudor.

The Tudors encouraged the development of trade, industry and the nascent bourgeoisie. But the new dynasty was unstable, its legal foundations very shaky. Both Henry VII and his son Henry VIII were faced with plots and revolts that threatened to thrust England back into civil war. For this reason, the majority of the upper classes and middle classes were fervently loyal to Elizabeth, who seemed to stand between them and a return to the chaos that they feared.

This was an age of great insecurity in which conspiracies, political intrigue and rebellion were always in the air. Shakespeare’s great contemporary, Christopher Marlowe, who had earned great popularity and success with plays such as The Jew of Malta and Tamerlane, was killed in a pub brawl, apparently because he was suspected of being a spy.

Elizabeth herself lived in a permanent state of anxiety, fearing assassination at the hands of discontented Catholics or Spanish agents. Her person was guarded by a vast network of spies and informers under the ever-vigilant Walsingham, one of her most loyal ministers. There is a portrait of Elizabeth that was painted in her old age. Her face has been heavily made up. In order to hide the ugly reality beneath it, it is painted white. She is dressed in magnificent silks and satins and covered in priceless jewels.

But a closer inspection reveals a curious and rather macabre detail. Her dress is decorated with human eyes and ears. The meaning of this is perfectly clear: “My eyes and ears are everywhere. I see what you are doing, I hear what you are whispering, I can read your innermost thoughts and penetrate the secrets of your heart and soul.” In a word: Big Sister is watching you.

Nowhere is this peculiar world of intrigue, plots and assassinations better described than in Julius Caesar. Here the psychology that drives ambitious politicians is dissected with the accuracy of a skilled surgeon. Julius Caesar is yet another tale of Machiavellian intrigue and backstabbing (literally) that faithfully conveys the essence of the political life, not just of the late Roman Republic but of every other period in history, especially our own.

Looking around him at the faces of his future assassins, Caesar comments with a wry sense of humour:

“Let me have men about me that are fat;

Sleek-headed men and such as sleep o’ nights:

Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look;

He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.”

Anthony tries to reassure him:

“Fear him not, Caesar; he’s not dangerous;

He is a noble Roman and well given.”But Caesar is not fooled, replying:

“Would he were fatter! But I fear him not.”

(Julius Caesar, Act one, scene ii)

In Henry VI, the Duke of Gloucester (the future king Richard III) says:

“Why, I can smile, and murder whiles I smile,

And cry ‘Content’ to that which grieves my heart,

And wet my cheeks with artificial tears,

And frame my face to all occasions.”(Henry VI Part Three, Act three, scene i)

Here in a few lines we have the distilled essence of what we now call Machiavellianism. It is a chilling echo of the words put in the mouth of Donalbain in Macbeth: “There’s daggers in men’s smiles.” In the same play Duncan, musing over the death of the Earl of Cawdor, utters the following words:

“There’s no art

To find the mind’s construction in the face.

He was a gentleman on whom I builtAn absolute trust.”

(Macbeth Act 1, scene iv)

All this is a faithful reflection of the mood of the times. Despite its external appearance of glitter, the myth of “Merry England” in Elizabethan times was just that – a myth. It was an age of extreme insecurity, where plots of assassination were ever present, spies were listening at every street corner and in every tavern, and the air was thick with fear and suspicion.

Elizabeth herself was steeped in the habits of a mind characteristic of Machiavellianism. She spent most of her life eaten up by suspicion and fear of assassination. Against real or imagined enemies, she showed herself to be utterly merciless. A man could be her favourite one moment, only to find himself a prisoner in the Tower of London awaiting execution the next.

An opportunist with few principles other than that of personal survival, her religious beliefs always came second to that principle. Even in her persecutions, she lacked the conviction of her late brother Edward, a fanatical Protestant, or her sister Mary, and equally fanatical Catholic. Mary burnt hundreds of people she regarded as heretics in order to save their souls. Elizabeth hanged or cut off heads, not to save souls but to serve herself, her interests and her throne.

Shakespeare’s attitude to revolution

Shakespeare’s plays can tell us a lot about life at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century. This was a time of tremendous political and social turbulence. One play in particular had a significant role in political events. Here Shakespeare’s involvement in politics – albeit an indirect one – could have ended very badly for him. This occurred towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, when she was already an old woman and speculation about the succession was becoming acute.

As a rule, the message of Shakespeare’s history plays is pro-monarchical and in that sense conformist. For obvious reasons he wished to acquire the favours of the ruling monarch – both Elizabeth and later James I. The reason for this was not merely pecuniary. Shakespeare and his generation had every reason to fear political instability. Their psychology was rooted in the experience of recent events. The memory of the Wars of the Roses was still vivid in people’s minds.

Yet in several of his plays Shakespeare gives free rein to subversive and even revolutionary thoughts. Shakespeare was capable of seeing the world from every conceivable angle. Although he was from a relatively privileged background, he was capable of understanding the misery and sufferings of other people. He lived at a time when colonialism was at its earliest beginnings. White Europeans were coming into contact with people of different colour, religion and customs. The result was a violent clash of culture that generally did not have a happy ending.

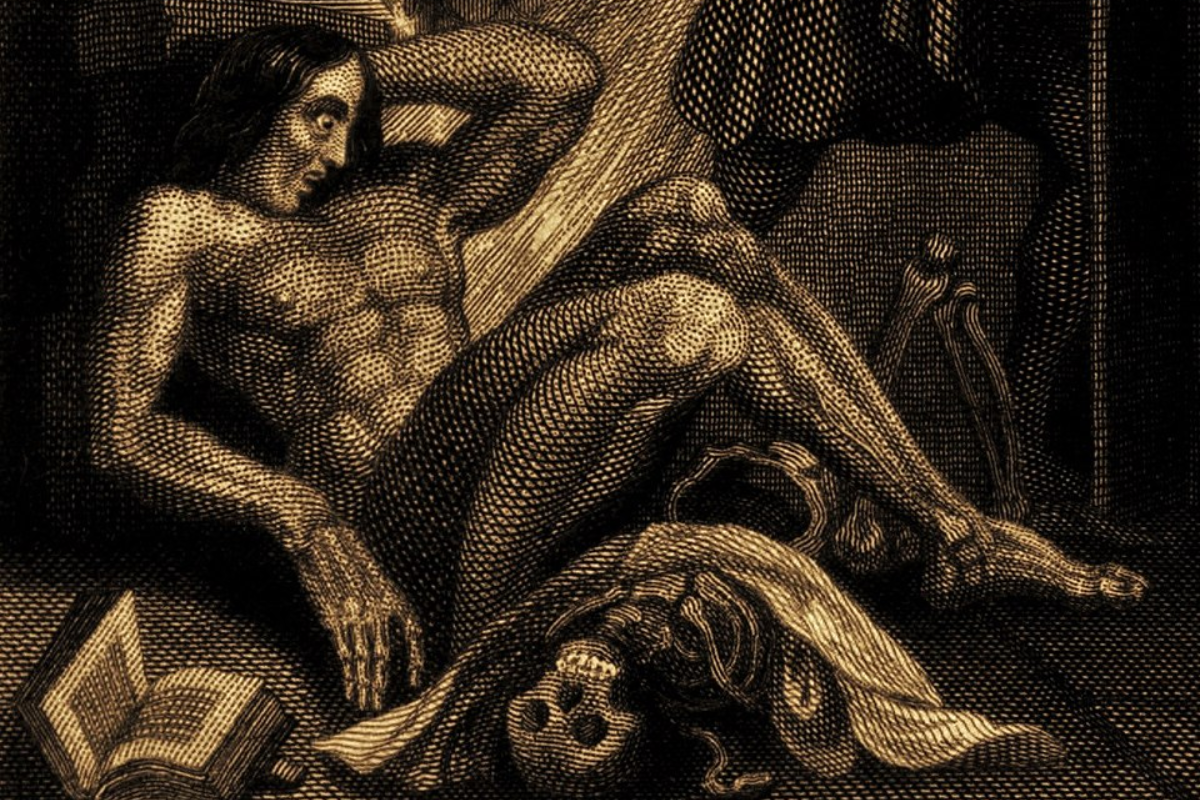

In The Tempest, Shakespeare’s last play, we find a startling denunciation of colonial slavery. Caliban is a monstrous being living in a state of savagery who has been enslaved by the wizard Prospero, the leading character in that play. The latter is portrayed as a magician and a highly knowledgeable person. According to some critics, Prospero is the depiction of Shakespeare himself as a powerful man of the Renaissance. Yet Shakespeare puts into Caliban’s mouth a speech that eloquently expresses the revolt of the slave against his master:

“You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you

For learning me your language!”(The Tempest, Act 1 scene ii)

London itself was a very violent place in those days. There were frequent riots, mainly by poor apprentices who expressed their frustrations in attacks on gentlemen’s serving men, foreigners and prostitutes. Such disturbances were regarded by the City authorities as a normal part of life. Far more serious were the rebellious outbursts in rural areas. These were provoked by the enclosure of common land, wastelands, and forests by greedy landowners and agents of the Crown.

Such popular anti-enclosure protests were fairly common in Shakespeare’s time, especially in the period from 1590-1610. They generally consisted of tearing up hedges and filling in ditches. Women and children participated in these actions. Small village riots, which were very common, were considered a misdemeanour. But on a larger scale they were punishable as treason. The largest, known as Kett’s Rebellion, involved 16,000 peasants. The leader Kett died in jail. He was fortunate not to have suffered a worse fate.

Cade’s rebellion

There is a challenging of authority in Hamlet, Julius Caesar and Richard II. Yet Shakespeare was no social revolutionary. The message of Shakespeare’s great history plays is precisely this: a warning against the chaos of civil strife – and revolution. The only explicit depiction of social revolution in Shakespeare is contained in the play Henry VI part 2.

The facts of the case are as follows. During the chaotic reign of Henry VI the peasantry, maddened by the increasingly heavy burdens of taxation and other oppressive measures, rose in revolt. In June 1450 an army of 20,000 rebels from Kent marched on London under the leadership of a man calling himself John Cade. Cade, who was reputedly an Irishman, defeated the forces sent by the King against the rebels and killed their commander, Sir Humphrey Stafford.

In Henry VI, Lord Say describes Kent as:

“the civil’st place of all this isle:

Sweet in the country, because full of riches;

The people liberal, valiant, active, wealthy.”

Yet in the same play the men of Kent are depicted in negative terms, as senseless, riotous, unruly rebels against authority. But this judgement appears to be both one-sided and unjust. As was usually the case in all such uprisings during the Middle Ages, the rebels claimed to be fighting, not against the King, but against his ministers, specifically the royal treasurer, Lord Say. These demands were well received by the people of London and also by the soldiers in the King’s army. Despairing of victory, the king fled to the relative safety of Kenilworth.

Henry’s fears were well founded. As the rebels approached the capital the King’s army melted away, its soldiers refusing to fight the rebels who maintained an admirable level of discipline. The rebels entered London with no resistance, and captured Lords Say and Cromer, who they beheaded. But thereafter the movement seemed to lose its sense of direction and degenerate into mere rioting. Cade had issued orders that there be no pillaging or theft. But some of the rebels began to plunder the homes of the rich, provoking a backlash against them. The rebels were forced to leave London and Jack Cade fled to Kent where he was murdered by a sheriff, allegedly while hiding in a garden.

The impression one gets when reading the version presented by Shakespeare in his play Henry VI is an unfavourable one. It reflects the fears of the Elizabethan upper classes of the mass of downtrodden and oppressed people who represented a constant threat to their privileged situation. The Elizabethan gentry must have felt that they were sitting on the brink of a large and dangerous volcano that at any time could erupt with elemental violence. These fears clearly coloured Shakespeare’s portrayal of Jack Cade and his rebel army. Cade is made to say:

“We will not leave one lord, one gentleman;

Spare none but such as go in clouted shoon,

For they are thrifty honest men, and such

As would, but that they dare not, take our parts.“But then are we in order when we are most out of order”,

Cade is supposed to have said:

“I thank you, good people: there shall be no money;

all shall eat and drink on my score.“Seven half-penny loaves (3 1/2 cents) shall sell for a penny.

“All the realm shall be owned in common — no private property; just take what you want.

“All shall wear the same livery, that they may agree like brothers, and worship me their lord.”

At this point Dick the Butcher shouts the famous line,

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”

At that point, a clerk enters. Someone accuses the clerk of being able to write and read. Cade orders:

“Hang him with his pen and inkhorn about his neck.”

In the end Cade’s severed head was paraded through London and his body was left for “crows to feed upon.” The Elizabethan middle classes could sleep soundly in their beds once more.

We shall never know what Jack Cade actually did say, but the above lines sound suspiciously like what the defenders of capitalism constantly repeat today: that the idea of socialism is utopian, that we are promising people things which cannot be achieved, and misleading the “ignorant masses” with the promise of a fool’s paradise.

One thing is clear: William Shakespeare was no revolutionary. He supported the existing order of Elizabethan England, upon which his success was based. He supported the monarchy and considered all movements of the downtrodden classes to be at best misguided, and at worst a recipe for chaos and anarchy. Despite this fact, there are many elements in Shakespeare’s plays that show a keen understanding for the sufferings of the downtrodden, as well as what one might call “the common touch.” It is no accident that his plays found favour, not only with the prosperous middle class from which he came, but with the poorer layers of society.

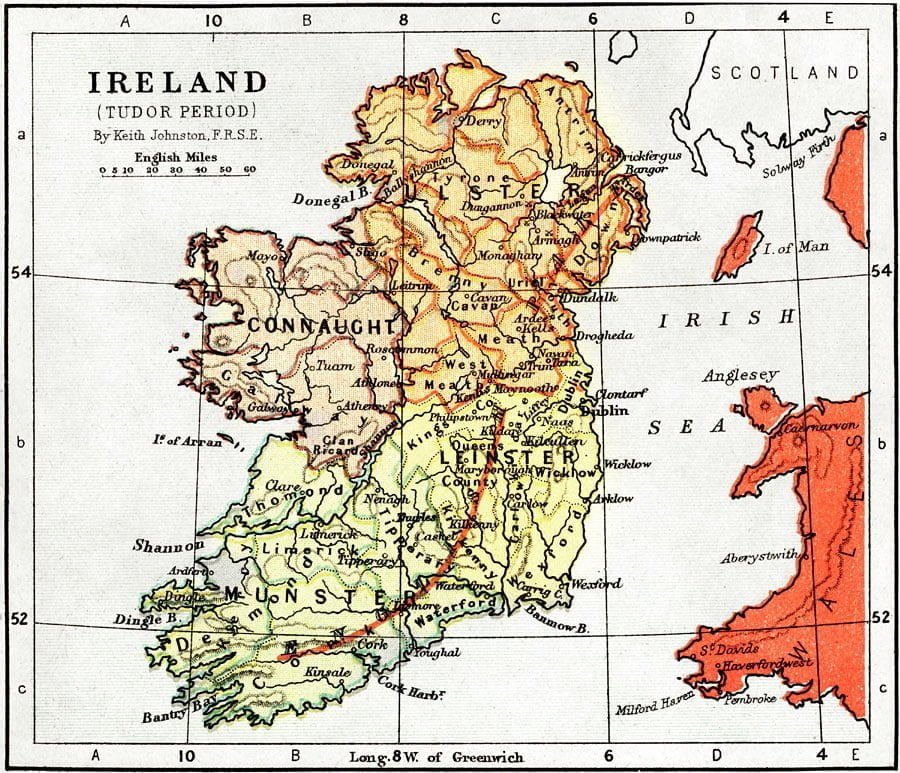

Ireland and the Essex Rebellion

Primitive accumulation not only signified the plunder and dispossession of the English peasantry but also the even more brutal dispossession of the lands of the Irish people. The Tudor period, and in particular the Elizabethan, was marked by the most ferocious oppression of the Irish. Here class oppression was mounted a thousandfold by national, religious and linguistic differences.

Primitive accumulation not only signified the plunder and dispossession of the English peasantry but also the even more brutal dispossession of the lands of the Irish people. The Tudor period, and in particular the Elizabethan, was marked by the most ferocious oppression of the Irish. Here class oppression was mounted a thousandfold by national, religious and linguistic differences.

Ireland was England’s first colony and the real cruel face of the English ruling class can be seen by its treatment of the Irish people. The Irish were treated as slaves and criminals, aliens in their native land. English soldiery butchered men, women and children without mercy, exterminating entire communities. For the English overlords, the Irish were not human beings but little better than animals without any rights, including the right to life.

As a result, there was a whole series of bloody uprisings and rebellions, ruthlessly put down by the forces of the English crown. The most serious of these was the rebellion of an Irish Ulsterman, Hugh O’Neill (Aodh Mor O Neill), earl of Tyrone, who repeatedly defeated the English forces and was making overtures to Spain, inviting military intervention in the pursuit of their common Catholic cause.

The English crown was spending a lot of money and losing an increasing number of men in this sanguinary conflict. England’s darkest hour in Ireland came on 14 August, 1598, when the English forces were cut to pieces at the battle of the Yellow Ford in County Armagh. 2,000 Englishmen, including its commander, the marshal of Ireland Sir Henry Bagenal were killed. Already in command of Ulster and Connacht, O’Neill’s army advanced rapidly into Leinster and then Munster.

In this desperate situation Elizabeth sent one of her “favourites”, Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex to Ireland with a huge force of 17,000 foot soldiers and 1,500 horsemen, 2,000 of these being veterans transferred from the Low Countries and with the promise of 2,000 more to come. Two years earlier Essex became a national hero when he shared command of the expedition that captured Cadiz from the Spanish.

With such a large force as this “the hero of Cadiz” could hardly fail to crush the Irish rebels. But fail he did. Devereux seems to have been a spoilt aristocratic brat with strong narcissistic tendencies. Excessively fond of his personal appearance (he wore his hair long) his tender self-regard was not replicated by courage and foresight on the battlefield. His military campaign failed miserably. He behaved like a coward whose only successes were in perpetrating the usual massacres of Irish men, women and children.

In the end, he fell into a trap carefully set for him by O’Neill. The latter offered him a truce, which he accepted with alacrity. He then entered into a private discussion of terms with the Irish rebel. This was a bad mistake. When Elizabeth found out about it she flew into a fury, suspecting treachery. To make matters worse, Devereux hastened to London to explain himself to his erstwhile mistress, bursting into her bed chamber in his riding boots, his cloak bespattered with mud for greater effect.

Effect his dramatic entrance undoubtedly had. Elizabeth, who now required several hours every morning for her serving ladies to paint her face white, dress her in finery and do everything possible to cover up the ravages of old age, was not at all accustomed to men – even former lovers – appearing unannounced at her bedside in this state of undress. Devereux had committed the most unforgivable faux pas, and would pay for it dearly.

One of the more endearing aspects of the Earl of Essex was his unstinting devotion and assistance to the arts. He befriended Shakespeare and attended his plays, his favourite apparently being the tragedy of Richard II. The play tells the story of the last two years of Richard II’s reign and how he was deposed by Bolingbroke – the future Henry IV – imprisoned and murdered.

On Saturday, 7th February, 1601, just two years before the death of the aged Queen, Shakespeare’s company was asked to perform the play Richard II at the Globe Theatre. It was to play a fatal role in the plot that was hatched by the Earl of Essex after he had suffered disgrace and banishment from the court.

Shakespeare wrote and published Richard II around 1595. The parallels between the ageing queen and Richard II were too uncomfortable. It is clear that Elizabeth was aware of the political parallels between herself and Richard II, and of the potential ramifications.

The Virgin Queen, as she liked to be known, had no children. Next in the line of succession was Mary Queen of Scots, whom she had executed while cynically blaming other people. The most likely candidate after this was Mary’s son, King James VI of Scotland. Although he himself was undoubtedly inclined towards Catholicism, James was more pragmatic than his mother, whose infatuation with Catholicism led her straight to the executioner’s block.

Since James had let it be known that he was open to do a deal with the Protestant party in London if he came to the throne, a faction of the English nobility saw James as a likely candidate and entered into contact with him. Among these was almost certainly Robert Devereux. This was the turbulent political and social background to Shakespeare’s plays of the period 1590 and 1613. The play shows the overthrow of Richard II by a group of rebellious nobles. The fall of the king is depicted in the following scene:

NORTHUMBERLAND

“My lord, in the base court he doth attend

To speak with you; may it please you to come down.KING RICHARD II

“Down, down I come; like glistering Phaethon,

Wanting the manage of unruly jades.

In the base court? Base court, where kings grow base,

To come at traitors’ calls and do them grace.

In the base court? Come down? Down, court!

down, king!

For night-owls shriek where mounting larks

should sing.”(Richard II Act 3, Scene iii)

In the given context, the play was provocative, politically subversive and even treasonous. Supporters of Robert Devereux paid Shakespeare’s company forty shillings – well above the normal rate – as a bribe to perform the play on the appointed day and hour. It was intended as propaganda to convince the public of the righteousness of the rebels’ cause.

The very next day, 8th February, Devereux marched into London at the head of 300 armed men hoping to seize the crown. But their hopes were soon dashed. The people did not rise and the rebellion ended in a farce. Essex was captured and on 25th February, 1601, he was beheaded as a traitor. It is said that Elizabeth wept bitterly for the fate of her former lover. But then she is said to have wept about the fate of Mary Queen of Scots and other of her victims. Just how sincere these tears were is anyone’s guess, but none of them served to stop the axe from falling on its target.

Were Shakespeare and his company aware of the real significance of the play they were asked to perform? Or were they enticed by the extra money on offer? Either way, they got off very lightly. Some members of the audience were arrested and executed for treason, but no charges were made against Shakespeare or the actors.

Did Elizabeth herself realise the meaning of the play? William Lambarde reported that in August 1601 he had a conversation with the Queen in which she said, “I am Richard II, know ye not that?” The authenticity of this statement has been questioned – like many other things. But I would like to think it was true. In a supreme act of historic irony, Shakespeare’s company was commanded to perform Richard II at Whitehall in the presence of the Queen herself on Shrove Tuesday 1601 — the day before Essex’s head was parted from his shoulders. Maybe the old Queen was enjoying a private joke at his expense.

A new reign

If the Earl of Essex had had a little more patience he could have achieved his objective and kept his head. In 1603, James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. England, Scotland and Wales were now united under one crown. Possessed of a sharp intelligence, and an even sharper instinct for self-preservation, James was an expert in the black arts of manoeuvre and intrigue. For years he had been plotting to take the English throne (to which he had a claim, though not a particularly strong one, by right of descent) once Elizabeth had gone to a better world. There is little doubt that he was involved in the Essex plot. James immediately released the surviving members of Essex’s faction from prison.

If the Earl of Essex had had a little more patience he could have achieved his objective and kept his head. In 1603, James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. England, Scotland and Wales were now united under one crown. Possessed of a sharp intelligence, and an even sharper instinct for self-preservation, James was an expert in the black arts of manoeuvre and intrigue. For years he had been plotting to take the English throne (to which he had a claim, though not a particularly strong one, by right of descent) once Elizabeth had gone to a better world. There is little doubt that he was involved in the Essex plot. James immediately released the surviving members of Essex’s faction from prison.

As King of Scotland, a relatively poor country, James was unable to indulge himself in the kind of extravagances to which he aspired. Now, with the English exchequer brimming with stolen Spanish gold at his disposal, the king could afford to be generous with money. His court was known for its lavishness and extravagance, but it was also a nest of intrigue, and jockeying for position. James had his favourite courtiers – usually good-looking young men – who received exquisite gifts. His romantic attachments might, of course, have been merely an expression of “passionate physical and spiritual love.” But that did not prevent people from speculating that these relationships were of somewhat more than a platonic nature.

Under King James the theatres flourished as never before. Shakespeare was the immediate beneficiary of his lavish generosity. His company was awarded a royal patent. At the king’s invitation, Shakespeare’s theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, became known as the King’s Men, and they produced new works under his patronage. It was during King James’s reign that Shakespeare wrote many of his most celebrated plays dealing with the struggle for political power. Among these are King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra and, of course, Macbeth.

Having so recently come close to disaster in relation to the late Queen Elizabeth, Shakespeare was anxious to get into the new monarch’s good graces from the beginning. To this end he composed one of his greatest plays. Written early in James’s reign, Macbeth (“the Scottish play”) was clearly composed as a means of impressing the new monarch. The play pays tribute to the king’s Scottish ancestry, presenting James’s ancestor Banquo in a very flattering light, while the presence of the three witches was designed to please a man who was obsessed with the subject of witches and witchcraft.

Already when he occupied the throne of Scotland, James saw himself as sacred. He also felt that he had a special insight into the agents of Satan. He had a morbid fear of a violent death and saw witchcraft as an evil that threatened his divine rule. Before his reign, witchcraft persecutions had been rare in Britain. While thousands of alleged witches were burnt on the European continent, only a relatively small number suffered that fate during Elizabeth’s reign. But James changed all that. In 1590 he had personally overseen the North Berwick Witch Trials. Over seventy people were accused of raising the storm that nearly sank James’ ship when he sailed home from Norway with his new bride, Anne of Denmark.

The precise number of people burned at the stake as the result of this trial is unknown. But thousands of Scottish women and some men were to be accused of witchcraft, tortured and killed, especially after 1597 when James published a book on Demonology. When he became king of England, James brought his views on witchcraft south of the border where the laws against it were rather less harsh than in Scotland. Only one year after James ascended to the English throne, he passed a new Witchcraft Act, which made “raising spirits” a crime punishable by execution.

James liked to hold lavish celebrations and masques for the court nobility. The services of such an accomplished writer as Shakespeare were very welcome to him. And he was prepared to pay the bills. Macbeth was the first English drama to depicted witches gathering in secret to perform their devilish rites. Performed for James’s court in 1606, the play presumably met with his most enthusiastic approbation. One doubts that this enthusiasm was shared by the poor wretches who paid with their lives for His Majesty’s morbid fantasies.

The lavish lifestyle of James I’s court led inevitably to equally lavish debts. The king’s subjects were naturally presented with the bill. Parliamentary disputes over the king’s debts doubtless took some of the shine off the joys of court life. But it continued on its merry way regardless. Ultimately the debts he left to his son and successor Charles I led to a conflict between king and parliament that led directly to Civil War and Revolution. But that is another story.