Can this be true? In the land of warm beer and test matches

in cricket that last five days without a result? This is what happened then.

The times of the post-War boom were fat years for most

working class people. Living standards went up year after year and there was

virtually full employment. As a result the labour movement had built up

enormous strength.

But the golden era was coming to an end. The ruling class

could see it was time to settle accounts with the working class. In 1970, Edward

Heath’s Tories were elected and introduced a new repressive piece of

legislation against trade unions – the Industrial Relations Act and its

centrepiece, the National Industrial Relations Court to put workers in their

place.

The following episode is taken from Rob Sewell’s book ‘In

the cause of labour ‘.

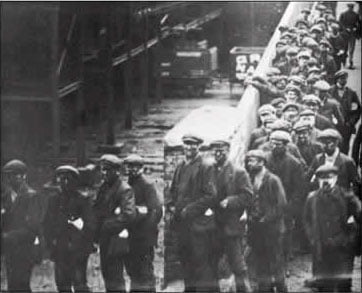

The preceding Labour

government had called time on casual labour on the docks – the humiliating

ritual of standing in line to be picked out by a charge hand or sent back home

without a job and a wage.

The dock strike to defend this reform was official,

supported by the dockers’ union, the TGWU.

The dockers picketed various warehouses that were technically not their

employers. They knew that –

- Secondary

picketing was effective picketing - Mass

picketing was effective picketing.

These are both activities that are currently illegal.

Under the Industrial Relations Act the union could be held

responsible for the actions of its members and fined. This secondary picketing

was actually a rank and file initiative.

The warehouses the dockers were picketing applied for an

injunction, a court order to stop. When the dockers disobeyed they were put in

prison – for being trade unionists and defending their livelihoods.

The TUC called a one day general strike. But organised

didn’t wait for this. Miners, print workers and engineers started to down tools

and walk out. An unofficial general strike was taking place under our old

slogan, ‘an injury to one is an injury to all.’

The ruling class backed down. They found the Official

Solicitor, a post invented six hundred years before for just this purpose, to

let the workers walk free. The capitalist class knew that no wheel turns unless

we say so. We have the power. We still do. We just have to discover it, as

workers did thirty five years ago.

The Road to Pentonville

Of all the great working class victories in history, the miners’ strike of

1972 stands out as one of the greatest. Since the beginning of the century, the

miners had been at the centre of all important working class struggles in

Britain. However the defeat of 1926 struck a heavy blow against the miners, who

saw their communities crucified by hunger and unemployment. After decades of

keeping their heads down, the miners had finally emerged victorious and given

the ruling class a bloody nose. It was their revenge for the heavy defeats of

the past. Moreover, since they were regarded traditionally as the advanced guard

of the British proletariat, the miners’ victory was regarded as a triumph of the

whole working class.

The miners’ victory had set alarm bells ringing in upper class circles. The

The miners’ victory had set alarm bells ringing in upper class circles. The

government was profoundly worried by the general spread of industrial and civil

disorder. A secret government report a few weeks after the miners’ strike

revealed, "A majority of shop floor workers lacked appreciation of the risks of

lawlessness and were easily led by comparatively few but energetic elements

intent on subversion." Another observer, Paul Ferris, stated: "The trade union

movement is more left-wing than at any time in its history� The idea of ‘direct

action’, of using unions for political ends, has revived after half a century."

(1)

The Civil Contingencies Unit was established under Brigadier Richard Bishop

in the spring of 1972 to deal with any such potential disorder. The CCU was kept

secret and its very existence was still officially denied a decade later. A

report in The Times revealed that "by early 1973 ministers had detailed

estimates of 16 key industries, their capacity for disruption, their importance

to the country’s well-being and the possibility of using alternative military

labour in the event of strikes." (2)

In the spring of 1972, after some trouble on the railways, a battle flared up

on the docks. The Tories had made no secret of the fact that they were keen to

get rid of the National Dock Labour Scheme, which protected dockers from the

indignities of casual labour. The Tory Cabinet nevertheless decided not to press

ahead, because, according to an internal report, "union officials were having

difficulty retaining control, in the face of increasing militancy at a local

level". However, their caution was upset by the news that two haulage firms,

Heaton’s and Craddock’s, had taken legal action against the TGWU for allowing

their members (unofficially) to boycott their haulage business in protest

against containerisation.

Typically, the NIRC under the chairmanship of Tory judge Sir John Donaldson

proclaimed that the TGWU nationally was responsible for their stewards’ actions

at the Heaton’s terminal and were in breach of the law. In the light of union

policy, the TGWU refused to attend the court hearing and was fined �5,000 for

contempt. Then, with the blacking still in place, an additional fine of �50,000

was imposed with the threat of total sequestration of the union’s assets if the

union failed to comply with the order to lift the boycott. The capitalist courts

had thrown down the gauntlet. But instead of calling a national strike of the

TGWU, which would have brought the country to a complete standstill within

hours, the union leadership decided to take its case to the TUC.

If the union leaders had gone at first to its own rank and file with an

appeal to defend the union, there is no doubt they would have been met with a

massive response. Then a call for solidarity could have been made to other

unions. Given the size and influence of the TGWU, a strike by this union alone

would have been equivalent to a general strike. But the leaders were not

prepared for this kind of showdown and decided on what they regarded as a safer

route. This proved a fatal mistake.

"The union was caught between the devil and the deep blue sea", stated Jack

Jones. "From the dockers there were increasing calls for a national strike; on

the other hand the threat of sequestration posed a challenge to the very

existence of the TGWU. Because of its size the TGWU was very vulnerable, but I

was still convinced that a collective response by the whole trade union movement

could defeat the challenge�

"In the event, when the General Council had had spelled out to it the need to

back the TGWU with all the consequences that might follow defiance of the court,

some of the members � according to one commentator � ‘ran like rabbits

frightened by gunfire’. A motion I proposed � ‘that the TGWU be advised to

continue the policy of non-co-operation with the National Industrial Relations

Court; that any financial penalty involved is accepted as the responsibility of

the TUC; and that a fund be organised for this purpose � was ruled out of

order by the chairman.

"At a later meeting a similar motion by Dick Briginshaw was shelved. The

majority on the General Council decided to hedge its bets; the TGWU was advised

to pay the fines and it was decided that unions should have the right to be

represented at the NIRC, without prior consultation with the General Council, ‘where

offensive actions were taken against unions or their members’. To sugar the pill

it was also agreed that, in the case of the TGWU, ‘a measure of financial

responsibility should be accepted by the TUC.’ In fact, when it came to the

point, a paltry �20,000 was paid to the TGWU. It was offered reluctantly and I

accepted it as a token rather than engaging in a dutch auction with Vic Feather.

I felt let down. I realised then how weak an instrument the General Council was,

and tried to get approval for the calling of a special congress so that the

whole movement could determine its position. I said there was a need to

re-establish unity against the Industrial Relations Act and to adopt positive

policies which would show that the movement meant what it said. Although I was

supported by Hugh Scanlon and others, we were defeated by fifteen votes to

eleven." (3)

Jack Jones, who was a genuine left-winger and a very sincere man,

nevertheless demonstrated a lack of understanding when he writes that the size

of the TGWU was a source of "vulnerability". This demonstrated a lack of

confidence in the ranks of the union on the part of even the best of the Lefts.

Some weeks later the dockers showed that they were clearly prepared to struggle

against the Tory government. But they now looked for a fighting lead from the

top. Unfortunately, no such lead was forthcoming, and the workers were left to

their own devices.

The T&G leadership was split with Jack Jones unfortunately arguing to

support the line of the TUC. When the vote was taken on the executive committee,

the decision of the TUC to pay the fines was carried by a wafer-thin majority.

The opposition to the Tory anti-union laws, so heroically taken up from below,

was coming apart at the top of the movement. Nevertheless, despite the wobbling

of the leadership, the dock shop stewards remained defiant and refused to lift

the boycott of the haulage companies.

Pentonville Five

A worried Tory Cabinet met to review the situation and discuss tactics. Its

memorandum of the 18 July 1972 recognised that an "unofficial shop stewards

committee still has support from many moderate-minded dockers because they fear

for their jobs." Options were then discussed: a state of emergency, rationing of

essential food, and the requisitioning of vehicles to transport food around the

country. But as the Cabinet wracked its brains for a solution, events began to

overtake them.

The haulage bosses sought a court order to halt picketing at the Chodham Farm

container depot, but were turned down by the Court of Appeal. However, the

Midland Cold Storage Company, which was also being blockaded, succeeded in

bringing its own injunction. On hearing the news, the dispute rapidly spread

throughout the London docks. On the evidence of private detectives, five dockers

were arrested and imprisoned in Pentonville Prison on 21 July. As the news

spread about the "Pentonville Five", the working class erupted. 44,000 dockers

and 130,000 other workers immediately downed tools in protest. Docks were

brought to a complete standstill at London, Liverpool, Cardiff, Swansea,

Glasgow, Bristol, Felixtowe, Leith, Chatham, Ipswich, Middlesborough and even

King’s Lynn. This was the magnificent spontaneous answer from the working class

to a direct attack on their organisations.

The movement spread like wildfire from below. Tommy Hilton, the spokesman for

the Swansea dockers said: "People must realise that this is not a dockers’

strike, but a strike in defence of trade union rights against the Industrial

Relations Act." Pressure mounted rapidly on the TUC General Council to act.

Belatedly they were forced to call (by 18 votes to 7) a one-day general strike

scheduled for 31 July. This was in complete contrast to the platitudes of TUC

general secretary Vic Feather, who had some weeks earlier dismissed the idea of

a general strike as a complete fantasy: "Such things happen in Italy and France,

but not in Britain", he had said.

The marvellous movement from below had the potential to develop into an

all-out general strike. Either the Tories would make big concessions, or the

whole situation threatened to spiral out of control. The TUC was reluctantly

forced to put itself at the head of this movement. They wished to steer it into

safe channels, but this was also extremely risky because if the one-day general

strike had gone ahead, there was no guarantee that it would last 24-hours. The

whole situation was extremely volatile.

Panicking, the Tory government called in the Official Solicitor, an obscure

unknown legal figure, to bail them out of the crisis. The law was now

reinterpreted to state that the Courts held the unions, rather than individual

pickets, responsible for their actions. The Pentonville Five were immediately

released and the general strike, to the utter relief of the TUC leaders, was

called off. The Times humorously compared the actions of the Tory government to

a "disordered slot-machine, which produced a succession of unforeseen results,

mostly raspberry flavoured."

On 28 July, when dockers struck again over job security, the government

declared another state of emergency. The question of sending in the troops to

break the strike was raised, then dropped like a hot potato. A few days later, a

government contingency group reported, "If troops were used there is a real

danger of sympathetic action by lorry drivers and others which would be more

damaging than the present situation." The dockers’ national shop stewards

committee stepped up their campaign to close all ports using unregistered

labour. By mid-August the Tory government was forced to accept a deal to end the

action.

A further skirmish over the Industrial Relations Act occurred when the

engineering union, the AUEW, was fined �55,000 on 1 December 1972, for refusing

union membership to James Goad, a scab, lay preacher, and crusader for the "freedom

of the individual". The union’s refusal to pay resulted in the fine being

sequestrated from the union’s funds by the Courts. In the face of this blatant

attack on trade unionism, 750,000 workers struck unofficially. The AUEW

leadership, however, confined themselves to verbal protests. In reality, as the

dockers had shown, the only effective means of crippling the anti-union laws was

through the militant actions of the mass movement. But the leaders of the trade

unions, both right and left, did not relish the prospect of a direct challenge

to the Tory government, and they recoiled.

Shrewsbury trial

1972 saw not only the first official miners’ strike but also the first

official building workers’ strike since the 1920s. Building workers, whose

separate unions merged to form the Union of Construction, Allied Trades and

Technicians (UCATT) in 1971, staged their national stoppage for �30 for a

35-hour week, and for the abolition of lump (self-contract) labour. The 13-week

strike resulted in increased union organisation and the biggest single rise ever

negotiated in the building industry. Again, the key weapon in this struggle was

the use of flying pickets that toured around the construction sites ensuring the

strike was solid.

The Tory government was desperate to contain the situation and stop the mass

picketing. They decided to achieve this by making an example of those guilty of

mass picketing, by framing them on charges of intimidation, violence and

conspiracy. They hoped this would stop the militant workers and act as a

deterrent to others. As a consequence arrests were made of two-dozen leading

building workers in the North Wales area. The trial of the "Shrewsbury 24", as

it was called, was a political trial. It was a deliberate conspiracy of the

Employers’ Federation, government and state, to frame the men and demonstrate to

everyone that militancy does not pay.

"I have heard the judge say that this was not a political trial, just an

ordinary criminal case, and I refute that with every fibre of my being�"

stated one of the accused, Ricky Tomlinson. "I look forward to the day when the

real culprits, the McAlpines, the Wimpeys, the Laings and the Bovis’ and their

political bodies are in the dock facing charge of conspiracy to intimidate

workers from doing what is their lawful right � picketing."

Des Warren was just as defiant.

"Mr Bumble said ‘The law is an ass’. If he were here now he might draw the

conclusion that the law is quite clearly the instrument of the state to be used

in the interests of a tiny minority against the majority." (4)

In the end, six men were found guilty in the capitalist courts of unlawful

assembly and three of affray. On appeal, the charge of affray was quashed.

McKinsie Jones, Des Warren, and Ricky Tomlinson were found guilty of conspiracy.

The latter got nine months, three years and two years respectively. In the

subsequent trials, pressure was brought on defendants to plea guilty to unlawful

assembly to avoid the charge of conspiracy. Some accepted the deal, while others

steadfastly refused. Brian Williams, Arthur Murray and Mike Pierce were

subsequently found guilty on unlawful assembly and affray and were given

sentences of six months and four months concurrent.

In the last of the trials, Terry Renshaw, John Seaburg and Lennie Williams

again refused to plead guilty to unlawful assembly. Seaburg was found guilty on

both charges and got suspended sentences of six and four months, while Renshaw

and Williams were found guilty of unlawful assembly and given suspended

sentences of four months. These were class laws passed against those who

challenged the employers and their state, every much as those against the

Tolpuddle Martyrs or the Glasgow spinners. Now as then, the spirit of these men

was not broken.

Des Warren wrote optimistically from his prison cell:

"I was greatly encouraged by the sentiments expressed in it as in all the

other messages of support my family and myself have received from comrades and

fellow workers from all over the country. I tend to be something of an optimist

and so tend to put setbacks such as the position Mac Jones, Eric Tomlinson, me

and our families find themselves in, in their right perspective and gauge them

against the advances made.

"Through their attack on the trade union movement and workers’ reaction to

it, in the form of ‘Free the Three’ campaign, new links, contacts and

friendships have been made and unity is being formed as with the miners’ fight,

which will last until long after we are out of prison and which will stand the

movement in good stead in the continuing struggle, for these reasons I believe

our time in prison will not have been in vain and I look forward to my day of

release so that I can rejoin that struggle, not with a feeling of bitterness or

revenge but with a strengthened resolve to help bring about a socialist Britain."

(5)

Scandalously, despite the campaign of protests, Warren and Tomlinson were

left to serve the remainder of their prison sentence under a new Labour

government, which came to power in February 1974. The Labour Home Secretary, Roy

Jenkins (who crossed the floor and ended up as a Lord) refused to "compromise

the law of the land". Ricky Tomlinson was released on 25 July 1975. Des Warren

was then left isolated in prison. At the end of his sentence Des Warren served

six months in solitary confinement, was reported on 36 occasions by prison

officers and moved 15 times through ten different prisons.

Maltreatment in prison undermined Warren’s health and destroyed his family

life. Tragically, he contracted Parkinson’s disease. Such was the pressure on

Warren and his family that in February 1976 his wife Elsa suffered a nervous

breakdown and their five children were taken into care. The stress finally

resulted in a family break-up and eventual divorce. Today, Des resides at home

in the North East, crippled by illness, and remarried to his former carer Pat.

The last time Des Warren appeared in public was three years ago at the Durham

miners’ gala, but since then his health has continued to deteriorate. The

expense of his care was met by a trust fund set up by the Durham miners’

mechanics and the Wear Valley and District Trades Council. Eric Tomlinson, who

was blacked for his union activities, subsequently became famous as a result of

his acting career, but remains true, now as then, to the cause of trade unionism

and the working class.

1972 could be accurately described as the year of industrial insurrection.

23,909,000 days were lost through strikes � excluding about 4 million lost

through political action. Even if the figures for the miners’ strike are

excluded, only once, in 1919, was the number of strike days greater. Old

traditions of militancy were being reborn. This titanic movement on the

industrial front was also shaking up the Labour Party. Under the impact of this

militancy, Labour’s NEC also began to swing to the left. For the first time

since the 1920s, a left grouping emerged simultaneously on both the TUC General

Council and the Labour Party NEC.

As always, the right wing on the TUC General Council was still interested in

collaborating with the Tories. In April 1972, the TUC was invited to Downing

Street to meet Ted Heath and discuss the economic situation.

"Before this was reported to the General Council Vic Feather had a word with

me in a heavily confidential way", stated Jack Jones. "At that stage I was

opposed to such a meeting and I quizzed Vic, saying: ‘Why do you keep having

these private meetings? They may give the impression that we’re weak, when it’s

the government that’s taking a battering!’ His reply was: ‘We’ve got to talk.

Ted’s coming our way.’ He knew he was on an easy wicket with a majority of the

General Council, who at that time were opposed to confrontation with the

government. A motion objecting to the talks was defeated by 21 votes to 9.

"Should we talk to the government, if they want to talk to us? That question

became an issue the General Council debated over many months." However, in due

course, Jack Jones succumbed to the pressure and went along with it. "I became

convinced that it was in our members’ interests not to miss an opportunity of

changing the government’s mind." (6)

The right wing was desperate to avoid a confrontation with the Tories and

attempted to curtail the growing militancy from below. However, the Lefts had no

perspective for the movement. Instead of preparing the ground and mobilising the

workers to bring down the government, they dithered and prevaricated, and

eventually capitulated to the right wing on the General Council. When it came

down to it, they all had illusions about how they could influence the Tories

through discussion. They treated the whole affair as a polite conversation,

rather than a struggle of mutually antagonistic class interests.

These illusions did not take them very far. To their utter bewilderment, the

trade union leaders were shown the door by the government.

"Proposals and counter-proposals were argued over the table. The TUC and the

government spokesmen did most of the talking, the CBI contribution was very

limited", continued Jones. "Then, after countless hours of meetings, there was

an abrupt ending. To the surprise of the trade union side, Ted Heath declared

that certain important items we had been emphasising � pensions, rents, the

impact of EEC membership, Industrial Relations Act � were outside the scope of

negotiation. Such matters, we were told, were for the House of Commons to

determine. A rigid posture was suddenly adopted by the government; even to this

day I am unable to understand why.

"No one could have been more disappointed than Vic Feather. He had been a

firm supporter of the talks throughout and had taken at face value the

government’s claim that it was prepared to enter into a real partnership with

both sides of industry in the management of the economy. He felt that Ted Heath

had thrown away a golden opportunity."

Here Jack Jones reveals the real face of Toryism: "In place of talks we had

confrontation." But still the General Council, fearing the alternative, wanted

to convince Heath of the error of his ways: "The government must be given a

chance to get off the hook," pleaded Len Murray, the new general secretary of

the TUC. But it did not do them a bit of good. The door of Number Ten was firmly

closed.

In November 1972, the Heath government imposed "Phase One" of a statutory

incomes policy, which was met with muted response. This was later followed by "Phase

Two". After the tremendous struggles of the previous two years, there was an

inevitable ebb on the industrial front. The mass movement, which had reached

unprecedented heights, could not be sustained indefinitely, especially as no

clear alternative was coming from the top. After a period of prolonged

militancy, workers had to "take a breather" and take stock of the situation.

This lull in the movement continued for most of 1973. The number of days lost

through strikes declined dramatically. From a peak of 24 million strike-days

lost, the figure plummeted to just under 8 million. Despite the pause, the

number of shop stewards had risen to around 300,000 and trade union membership

was rising substantially, especially amongst white collar and professional

workers. With practically every layer of the working class involved in strike

action over the previous few years, confidence was very high. The possibility of

a general strike, given the provocative behaviour of the Tories, was implicit in

the situation. Britain had entered an epoch of sharp turns and sudden changes,

politically, economically and industrially.

The turnaround in the industrial situation took place towards the end of

1973, which coincided with the announcement of "Phase Three" of the Tories’

incomes policy. This now allowed a 7 per cent wage norm � well below the rate

of inflation. If accepted, it would mean a significant cut in living standards.

Earlier in the year, miners had rejected strike action over wages, however,

resentment began to build up. The Left had strengthened its position in the NUM,

and Mick McGahey, a leading member of the CPGB, had been newly elected as

vice-president. War in the Middle East led to the quadrupling of oil prices,

which tipped the world economy into the first major slump since the 1930s. This

energy squeeze served to increase the bargaining power of the miners. This was

put to full use in a new substantial wage claim. As part of a national campaign,

an overtime ban was introduced throughout the coalfields on 12 November.

In an attempt to isolate the miners, the Heath government hit back by

announcing a state of emergency and then on 1 January 1974, the introduction of

a three-day working week, ostensibly to save energy. Street lighting was cut

back and television was ordered to close down every night at 10.30 p.m. "Already

the country felt on the brink of a major crisis", stated William Whitelaw. (7)

By the middle of January more than one million workers had been laid off work. A

national ballot in early February recorded a massive 81 per cent majority in

favour of strike action � far higher than in 1972. The second national miners’

strike was announced for 9 February 1974. Fearing a humiliating repeat of 1972,

Heath gambled the fate of his entire government in a new general election. A few

days before the miners’ strike was due to begin, the dissolution of Parliament

was announced and a snap general election was called for 28 February.

As expected, the capitalist press attempted to whip up a campaign against the

miners, talking of an alleged threat to democracy. "Who runs the country?

Parliament or the militants?" were the banner headlines at the time. But despite

all the attempts by Heath to win a panic election, a decisive section of workers

and the middle class, sickened by the Tories, were looking to the Labour Party.

Reflecting the radicalisation on the industrial front, the Labour Party had

moved sharply to the left. In October 1973, the Party conference had endorsed a

radical programme that included the nationalisation of the top 25 monopolies.

Although the right wing still controlled the contents of the election

Manifesto and watered down the Party’s socialist commitments, it was still very

radical. Labour entered the election promising to "bring about a fundamental and

irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working

people and their families." Even the arch right-winger Dennis Healey, the shadow

Chancellor, threatened to "squeeze the rich till the pips squeaked".

The ruling class were alarmed by these developments:

"� the Labour Party has become a threat to the constitution, both in

Opposition and in government", stated the ex-Conservative Minister, Ian Gilmour.

"Extremists have penetrated it at every level, and swung it violently to the

Left. As Lord George-Brown said in April 1972, ‘in the fifties and sixties the

men at the head of the unions were genuine social democrats� Now, I think

today that the situation is different. The major unions are the subjects of a

different kind of leadership, with a different outlook.’ And he added shortly

afterwards: ‘We have been taken over. And we have been taken over by a

collection of people who call themselves "activists". But they are for the most

part people who do not believe in our way of life or in our social democratic

outlook� And these fellows have now captured control of the Labour movement at

every level; constituency parties; trade union branches; executives of the trade

unions; the General Council of the TUC; the Labour Party National Executive; and

the Shadow Cabinet." (8)

In the end, the whole panic election gamble backfired and the Tory government

went down to defeat. The Labour Party won 301 seats to the Tories’ 296. The

Liberals had managed to pick up 14 seats, and in theory held the balance of

power. Heath desperately tried to cling on to office, holding secret discussions

on 2 March with Jeremy Thorpe, the leader of the Liberal Party, in an attempt to

patch together some form of coalition. This farce turned to dust when the

Liberal headquarters was inundated with 3,000 telegrams of protest. The forlorn

attempt to cobble together a coalition government to keep Labour out of office

fell flat. It was a humiliating episode for Heath. And so on 4 March, with his

tail between his legs, he resigned. "This has been an historic dispute. It is

the first time that an industrial stoppage has provoked a general election and

indirectly brought about the downfall of a government", stated the editorial of

The Times a few days later. (9)

Labour once again came to power in early March 1974. On 11 March, the miners

returned to work with major concessions. On the same day, Margaret Thatcher

defeated Edward Heath to become the new leader of the Tory Party. The collapse

of the Tory government was certainly a turning point in the Labour movement. For

the first time in British history, an elected government had been brought down

by industrial action. "It was certainly the worst time in my political life",

recalled Tory minister Willie Whitelaw. Now, organised Labour looked to the new

Labour government to carry through its radical commitments, and, in particular,

sweep away the detested Tory anti-union legislation.

1- Paul Ferris, The New Militants, p.8, London, 1972

2- The Times, 13 November 1979

3- Jack Jones, op. cit, pp.247-48

4- Quoted in Jim Arnison, The Shrewsbury Three, pp.73 and 75, London 1974

5- Ibid, pp.10-11, London, 1974

6- Jones, op. cit, p.255

7- Whitelaw, op. cit, p.126

8- Gilmour, op. cit, pp.200-201

9- The Times, 7 March 1974