30 years ago, beginning on 24th January 1986, print workers at Murdoch’s printing presses began a year-long strike. Along with the Great Miners’ Strike, it was one of the most militant episodes of industrial action in Britain during the Thatcher years. Jim Brookshaw, a print worker at the time, recalls his experiences of the struggle.

30 years ago, beginning on 24th January 1986, print workers at Murdoch’s printing presses at News International began a year-long strike. Along with the Great Miners’ Strike, it was one of the most militant episodes of industrial action in Britain during the Thatcher years.

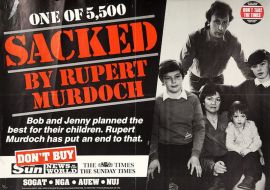

Prior to the strike, Murdoch had not yet gained the ruthless reputation that he has now. All illusions were quickly shattered by the News International boss’ overnight dismissal of 6,000 workers, in an attempt to destroy the printing unions, which had won significant control within the workplace through decades of organisation and militancy.

As with the miners, the full force of the state was used against striking print workers. Police were violently used to break up demonstrations and pickets, in order to guarantee that Murdoch’s papers could continue to be produced and distributed.

The Wapping print strike was a turning point for the industry and for the labour movement in Britain. Murdoch – with the help of the Thatcher government – had broken the backs of the printing unions, one of the most powerful sections of the trade union movement. The other media bosses followed suit, and soon all the printing companies had moved from Fleet Street, leaving thousands of workers on the scrapheap of unemployment.

After over a year without jobs or pay, the strike finally collapsed on 5th February 1987. It was to be the last major industrial action against the Thatcher government, until the so-called “Iron Lady” was defeated by the tremendous Anti Poll Tax movement.

We publish here a first-hand account of the events surrounding the Wapping print strike by Jim Brookshaw, a print worker at the time, who provides some background to the dispute and vividly describes the brutality of the police against the strikers.

For more information about the Wapping strike, visit the News International Wapping Dispute website.

The area of London where the national press was based was known as Fleet Street, but encompassed an area including Bouverie Street, Grays Inn Road, Farringdon Road, Holborn Circus and other places.

The area of London where the national press was based was known as Fleet Street, but encompassed an area including Bouverie Street, Grays Inn Road, Farringdon Road, Holborn Circus and other places.

National newspaper production was completely unionised and provided well paid and secure employment for thousands of workers. Workers belonged to a number of printers’ trade unions, the EEPTU electricians’ union and the AEU engineers’ union.

The workplace organisations were known as chapels, and shop stewards were known as the Father or Mother of the chapel. This comes from the early origins of printing in religious institutions.

It was the chapels, with their tight organisation, that were the main source of strength for print workers. Union officials were only seldom involved in the daily life of the chapels. However, it was also the case that this tight organisation of separate, often quite small chapels encouraged secrecy, which worked against unity across the workers in the print industry.

In the run up to 24th January there was no shortage of rumours about what was happening at Murdoch’s new plant at Wapping. The official company position was that a new newspaper, the London Post, was to be printed there.

The engineers’ chapel at Murdoch-owned the Sun and News of the World were involved in preparing maintenance plans for the new plant. They did not share this info with the Times and Sunday Times (Murdoch’s other papers) engineers until the eleventh hour. I believe they thought then that their jobs were safe in any move to Wapping.

Some of our printers believed that although the Sun could be produced at Wapping, the Times could not. In the end, the first paper produced at Wapping was a Times supplement.

At the last moment Murdoch called in the unions to present them with his demands. It is clear that the unions could not accept these demands and that a collision was inevitable. The engineers chapel at the Times / Sunday Times, meanwhile, were refused any talks or information. The two engineers’ chapels met very quickly and formed a united chapel.

As soon as the printing unions announced the strike, we were handed dismissal notices. 6,000 workers were sacked overnight, replaced by scab labour in the Wapping plant that Murdoch had organised from the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union (EETPU). The bosses had prepared themselves well and caught us on the hop.

This dispute was not just about the Murdoch organisation, however; the outcome would affect every print job in London and beyond. This was understood by Fleet Street workers, who dug deep to support those of us on strike and supported our marches and demos.

We were, of course, hampered by the Thatcherite anti-union laws, but they could have been swept aside. In any case, such laws mostly only bothered the union officials.

The Marxist tendency – the Militant – said at the time that this solidarity was great, but that without the development of a Fleet Street strike and a national strike, the movement was doomed to fail. And so it was to be.

Workers today can learn a great deal from the Wapping dispute. Only through unity and militancy, armed with a bold socialist programme, can we defeat the bosses and the Tory government that defends their system.

Twelve months at Wapping

Demonstrations and pickets were called to try and block production at Wapping and stop the distribution of News International’s papers. Our Fleet Street AEU branch organised the first march to Wapping. It was clear right away that the police and scabs were working to a well-rehearsed plan.

Thousands gathered in the highway. A sudden rush of police was forcing a way for scab lorries. I stuck up two fingers at a lorry and was pounced on by two “heroes in blue”. They held me, one on each arm and ran me at a wall. I went down and one of them swung round and hit the wall. They put me on a bus. Another one comes in with his helmet and stick. “You”, he shouts, “on the floor!” “Put me on the floor,” I replied. I remained on the seat.

The charge was “threatening behaviour”. Like pretty much everyone who got arrested, I was offered a bind over – that is, you plead not guilty and get bound over to be on good behaviour. If you reoffend, you get done for both offences. I was offered another bind over later on. Some lads had three or four bind overs. They arrested at random just to get you off the streets.

Now it’s Saint Davids Lane. Tony Dubbins (NGA General Secretary) has just been arrested. Old bill is lashing out at all and sundry. A woman is on the ground trying to get up, but one “brave” boy is standing on her scarf. I shove the bastard out of the way and help her up. I’m against a brick wall with a horses arse in my face. Two lads push in and lift me clear.

In one police riot they charged across the road, but one “hero” peels off and goes for Hazel (my wife), who is standing apart by a railing. He’s got his shield up and truncheon arm raised. I stick my arm between him and her and warn him. He runs off to join his mates.

Standing in the highway talking with Bill Freeman and John the lawyer. We are all badged up clearly. The filth charge, and as they go by one hits John across the face cutting him and smashing his glasses.

Next occasion: after a march, we are all gathered in the highway. The police are moving us on, but of course we don’t go quickly enough. They start pushing and shoving a group of our cleaning ladies, so I get in between to shield them (not that those toughies needed any shielding), so the cops arrest me! I’m offered another bind over, but I refuse it. The magistrate eventually threw it out.

I could go on, but there was nothing unique about my experience. Men and women were being shoved, battered, threatened and arrested all the time. The miners just a year before had worse than us. I relate these events to give you a flavour of what it was like, but words and pictures can’t portray the reality of being there.

Those of us involved will never forget the events of the Wapping strike. Above all, we will always remember the lengths that the bosses and their friends in government are willing to go to break up our unions, strangle workers, and increase their profits – lessons that are more valuable now, in this period of austerity and attacks, than ever before.