Twenty years ago, the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) was signed in Belfast. Its architects, the American, British and Irish governments, hailed it as marking the beginning of a new era. The thirty year cycle of violence, referred to as The Troubles, would be brought to an end and a period of peace, prosperity and cooperation would open up.

Greeting the signing of the agreement in November 1998, Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, said the following:

“Northern Ireland, once a barrier to understanding, represents now in terms of the Good Friday Agreement a shared determination to succeed. In the past, despite coordinated entry and shared partnership, we appeared to have different interests and a different outlook regarding the European Union. Today, I sense a greater convergence, now that the grip of ideology, both for and against European integration, has been loosened.”

Twenty years ago the likes of Ahern, Blair, Trimble and Clinton (and we must not forget Bono) were busy slapping each other on the backs. Today they are despised and irrelevant.

It is hard to believe that words such as these were only spoken twenty years ago. In a very real sense, they belong to another epoch, along with the people who spoke them.

Everything has been turned into its opposite. Where previously there was ‘convergence’ and ‘understanding’, now there is division and discord. Of the Northern Irish ‘centre-ground’ parties that were signatories to the GFA barely anything remains. Like centre-ground parties everywhere, the SDLP and UUP are shadows of their former selves.

And how are the ruling classes celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the GFA today? By quietly burying the very same agreement.

The end of the GFA?

Having signed the GFA, the British ruling class were content that they had put the issues in Northern Ireland to bed. As long as the killing was over, they couldn’t care less what happened there.

Having signed the GFA, the British ruling class were content that they had put the issues in Northern Ireland to bed. As long as the killing was over, they couldn’t care less what happened there.

The region had long ceased to be of any value to British capitalism. When they partitioned Ireland in the 1920s, the North represented 80% of the industrial output of the island. Today it represents less than 10%.

In January last year, however, the British capitalist class were forced to sit up and pay attention. Years of crisis had completely hollowed out the devolved regime established by the GFA at Stormont. The immediate cause of the collapse was just one more scandal. But it pointed to a more fundamental rot.

Life in the North of Ireland had become insufferable for the working class. More people have died in suicides over the last twenty years than were killed in the whole of The Troubles. Stormont had become little more than a collective trough in which the political exploiters of the different communities had their snouts buried and Sinn Fein were finally forced to pull the plug.

For apparently accidental reasons, however, the extremely volatile politics of the North of Ireland have been thrust to the centre of the British ruling class’s vital interests. First the Brexit vote raised the spectre of the border. Then the June election made the DUP kingmakers at Westminster.

With leverage the likes of which they’ve not previously enjoyed, the DUP MPs are suspected of having sabotaged the restoration of power sharing to help keep themselves relevant.

Direct rule

With no Stormont Executive, the Tory government have been forced to return one devolved power after another to London.

With no Stormont Executive, the Tory government have been forced to return one devolved power after another to London.

As if in mockery of the GFA, a quiet tipping point has been arrived at just weeks before its twentieth anniversary. The new Northern Ireland secretary, Karen Bradley, has set a £12 billion budget, including the first £400 million tranche of the notorious £1 billion bung that May promised the DUP.

What then is this if not the de facto restoration of direct rule from London?

In December, riding high from his ‘success’ in playing hardball with Britain in the Brexit negotiations, Ireland’s Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, demanded that there be no return to direct rule from London. In doing so he had the letter of the GFA on his side.

The GFA calls for the convening of a British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference (BIIGC). Varadkar’s call however was met with howls of protest from Tories and unionists about undermining British sovereignty. The Irish Times has meanwhile reported on Karen Bradley’s suggestion:

“[…] She reaffirmed the principles of the Belfast Agreement – then announced the British government would consider ‘different arrangements’ to devolution until an executive is restored, and invited the Northern Ireland parties ‘and others’ to make proposals on how ‘local decision-making and scrutiny on a cross-community basis might be achieved’.

“[…] Bradley’s statement has unilaterally put the whole lot up for casual renegotiation, entirely at London’s behest, without even the decency of a legislative order to keep it grounded in the law.”

Varadkar’s response to all this? He has backed off from his original proposal. After all, “whether it is done through the auspices of the [BIGCC] or not is not the most important thing.”

A remarkable admission. In passing, the setup of the GFA is admitted as having expired! The GFA is being violated willy-nilly. And what is remarkable is that no one seems to care!

The only question that evoked even mild controversy was the question of whether MLAs should continue to get their £50,000 salaries for sitting on their backsides!

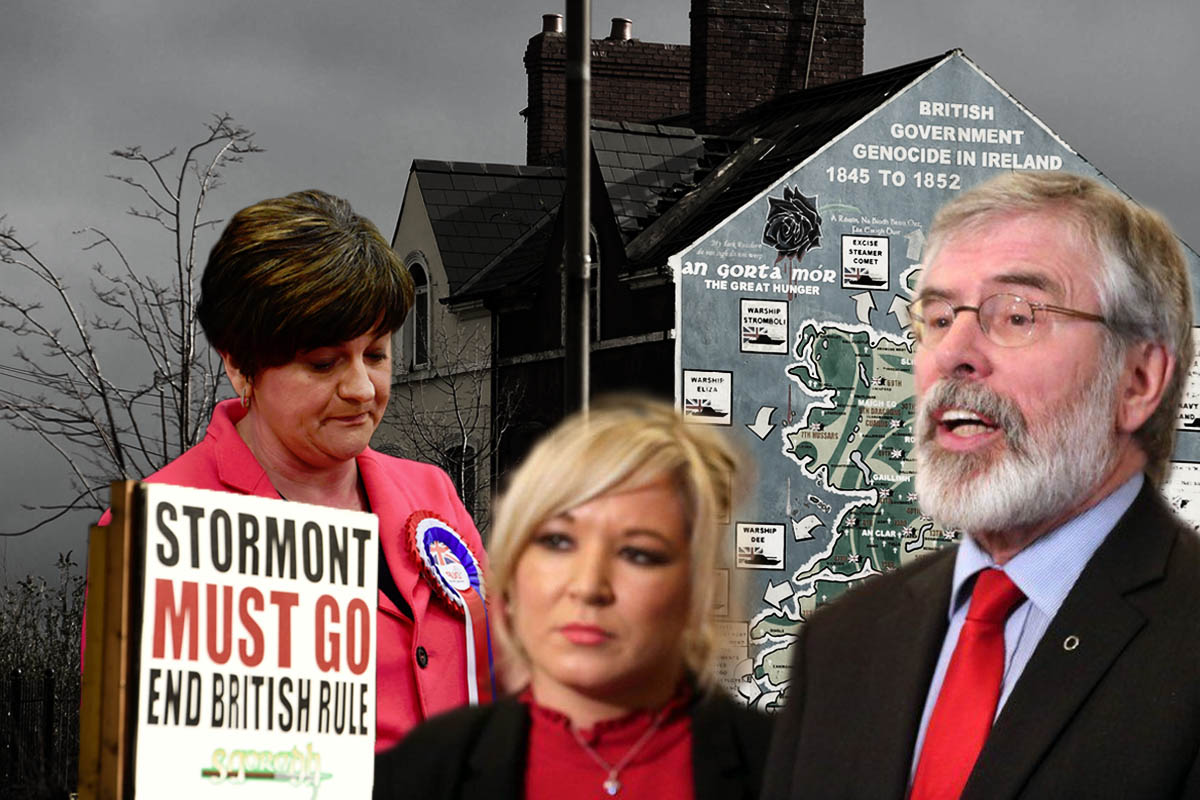

Meanwhile, everyone wants to pay lip-service to the GFA: Gerry Adams, Theresa May, Leo Varadkar, Michel Barnier – even Jacob Rees Mogg! All of them claim that they stand for its defence.

Like the parrot from Monty Python’s Dead Parrot sketch, everyone insists it is “just resting”. But the evidence suggests quite the contrary. It’s clear that few tears will be shed for institutions which have become utterly discredited and irrelevant.

The real question is how did we end up here? And what does this mean for the future?

Sectarian by design

It hardly needs to be stated that the GFA has utterly failed to remove the sectarianism from the politics of the North. Neither could it have.

It hardly needs to be stated that the GFA has utterly failed to remove the sectarianism from the politics of the North. Neither could it have.

Fifty years on from the Civil Rights movement and housing remains almost entirely segregated, as are education and basic services. Its immediately visible signs are the peace walls – some as high as five metres tall and visible for miles; the annual burning of Irish/Catholic effigies on the 12th July; and continuing sectarian violence.

Sectarianism is part and parcel of the statelet in the North of Ireland, the deliberate product of British imperialism. It is here and here alone that responsibility for this mess lies.

Periodically and quite consciously, loyalism has been whipped up by the British ruling class to divide the oppressed along religious lines. On no few occasions have Catholic and Protestant workers stretched out their hands across the sectarian divide to unite along class lines. Each time however, loyalist reaction served to cut across the developing class struggle.

In the 1920s Britain faced a revolutionary war in Ireland. Determined to retain its strategic and economic interests in the North, it signed a treaty with a section of the Republican forces (the ancestors of Fine Gael) to partition off a sectarian statelet in the North.

As James Connolly, the great Marxist, warned: such an act would be a betrayal of the Irish cause, and would unleash a carnival of reaction.

This is precisely what happened. When Catholic youth rose up against their oppression in October 1968, the British ruling class moved to see off revolution from below by enacting reforms from above.

The monster of loyalist sectarianism, however, headed by the likes of DUP founder, Ian Paisley, had other ideas. Loyalists gangs were incited to brutally attack Civil Rights marches and a pogrom atmosphere against the Catholic population was whipped up.

In reaction, thousands of Catholic youths turned to the Provisional IRA in self-defence. In 1969 the British Army was deployed on the streets of Northern Ireland, supposedly to protect the Catholic population. So began a 25 year cycle of violent bloodshed.

The Provisional IRA, however, lacked any understanding of how the national question was linked to the class question.

Although they paid lip service to the notion of a ‘Socialist Republic’ their aim was that of ejecting British imperialism by pure force and the unification of the North with the South of Ireland on a capitalist basis. The class question was left for resolution until the far distant future. Such a perspective – separating the national and the class question – could only lead to disaster.

In the words of James Connolly,

“If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organization of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers.”

Dominated by capitalism

We can see today how profoundly true those words really were. The independent South is no more free from imperialist domination than it was under direct British rule. The bosses have changed and their domination is less direct.

Today it is European and US capital that call the shots in South through the ECB, the IMF and the World Bank. But for that very reason their rule is all the more secure.

In fact, the more thinking representatives of the British ruling class would have loved nothing more than to be rid of the mess they’d created in the North. Today they regard it as a net drain to the Treasury of £10 billion a year. It is just one more source of political instability in a period of unprecedented crisis.

The bourgeoisie in the South, however, have no desire to take possession of the North either! When Varadkar and Simon Coveney mooted their desire to see a united Ireland late last year, the Irish bourgeois press issued a quick rebuke.

The unification of Ireland is only possible on the basis of a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism by united working class struggle across these islands.

The resort to purely military methods by the IRA was therefore completely doomed. A small group of irregular troops can never defeat a regular army, bristling with arms, unless it has the overwhelming support of the population – in other words, unless it raises the flag of social revolution. Instead the IRA thought it could force one million Protestant workers into a united Ireland by military means.

For Protestant workers, a united capitalist Ireland offered nothing. It would just see the pluses and minuses reversed and themselves transformed into a vulnerable minority.

Furthermore, the purely military character of the campaign of the IRA inevitably lead to a descent into ‘tit-for-tat’ sectarian revenge killings. The Protestant working class was thus pushed into the arms of the British state and the sectarian divide has grown into a chasm.

At any rate, the IRA were thoroughly infiltrated by British spies. Indeed, all paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland were riddled with such spies, through which the British state conducted an atrocious dirty war. But while the British state was never going to be defeated by the IRA, neither was it able to completely expunge the latter, who could constantly draw new recruits from the oppressed Catholic youth.

Cul-de-sac

By the 1990’s, the war had been fought to a stalemate and Irish unification was further away than ever before.

By the 1990’s, the war had been fought to a stalemate and Irish unification was further away than ever before.

The IRA were forced to admit the complete and utter bankruptcy of its methods of individual terror. In 1994, the IRA declared an unconditional ceasefire without having accomplished any of its aims. In 1998, under the terms of the GFA, this lead to the establishment of a devolved Northern Irish Assembly at Stormont.

Far from representing a new conquest, this was a rehash of the Sunningdale Agreement, which the British ruling class had placed on the table all the way back in 1973. For what purpose then was so much blood spilled?

The leadership of Sinn Fein tried to sell failure as a success. Gerry Adams hailed the GFA some years later as, “the foundation upon which new relationships between unionists and nationalists, and between Ireland and Britain, can be forged. It has opened up a peaceful, democratic route to a united Ireland.”

These words too have not aged well. The armalite was substituted by the ballot box. The military road to a united Ireland was substituted by a reformist road.

The Assembly set up by the GFA, however, has no power to steer such a course. In reality, it is little more than a glorified county council. It cannot raise its own finances and has actually enshrined sectarianism in Northern Ireland’s constitution.

The rules of power-sharing mean that there must exist majorities within both nationalist and unionist camps for anything to get done. This means that parties are encouraged to compete for the vote of ‘their’ community by any means.

Unionism, meanwhile, continues to hold a veto in the Assembly. This has been used to frustrate any steps forward on gay rights, abortion rights, an Irish Language Act, etc.

From a struggle for Irish unification, the rhetoric of Sinn Fein has moved on to fighting for ‘equality’.

Even here, Stormont has patently failed to deliver. Rather, all that has happened is that a thin stratum of the Catholic population has been raised into the middle class, whilst the working class – both Catholic and Protestant – has been left to fester in deplorable conditions.

It is these conditions of capitalism that breed resentment and nourish the roots of sectarianism.

A period of crisis

Unveiled with great fanfare and bold promises, the GFA was able to persist for a time. Quite naturally, when put to referendum in the North and South of Ireland, it was overwhelmingly endorsed by a people sick and tired of pointless bloodshed and deepening sectarianism. As long as the fighting had stopped and the boom continued, the institutions in the North could appear to get along.

Unveiled with great fanfare and bold promises, the GFA was able to persist for a time. Quite naturally, when put to referendum in the North and South of Ireland, it was overwhelmingly endorsed by a people sick and tired of pointless bloodshed and deepening sectarianism. As long as the fighting had stopped and the boom continued, the institutions in the North could appear to get along.

That has been thrown into chaos by the crisis since 2008 and the ensuing austerity. Unable to provide reforms, Stormont is capable of inspiring little more than disgust anymore.

A deep despair and anger is bubbling under the surface of society. But it is unable to find a clear and conscious expression. However confused, this anger is in reality a class anger.

Gone are the days when the Protestant capitalists could sow the illusion of a community of interests between themselves and the Protestant worker. On the one hand, sectarianism is being fanned by capitalism; on the other, there is an instinctive class anger developing in the depths of society.

The British ruling class are completely losing their grip on the situation as their system enters into crisis. The intelligent representatives of the ruling class such as John Major were utterly dismayed at the stupidity of May entering into a deal with the DUP. They know that she is playing with fire.

And there is another wing of the Tory Party – represented by insane reactionaries like Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees Mogg – who are completely unconcerned at how a hard border might stir up the situation in the North.

There also remain groups that continue to believe in the ‘armed struggle’. For these people, customs barriers and border posts would seem to be ideal targets.

This represents a toxic mixture. This is the future under capitalism: chaos.

For a socialist united Ireland

That being said, there are no few socialist Republicans who have drawn the lessons of decades past: both individual terror and reformism have failed.

That being said, there are no few socialist Republicans who have drawn the lessons of decades past: both individual terror and reformism have failed.

Marxists took an unpopular stand twenty years ago. We opposed the Good Friday Agreement and warned that it would end in tears, without solving a single problem. The events of the past few years have proven this prognosis wholly correct.

It is necessary now to return to the revolutionary, class struggle traditions that are the common heritage of all workers of Ireland: the traditions of Connolly and Larkin. Unity can only be achieved through common class struggle.

The task must be to overthrow capitalism and form a socialist, united Ireland as part of a socialist federation of Europe. This can only be achieved under the leadership of a party based on the revolutionary ideas of Marxism.