This article by Rob Jones was originally published in March 1976. Rob sadly passed away earlier this year. Our thoughts go out to his family and friends. We are republishing this article to commemorate his lifetime of dedication to the struggle for socialism.

Rob was recruited to Marxism at Sussex University in the 1960s, later becoming a leading member of the Militant. He remained a sympathiser of Socialist Appeal up to his death.

In 1976, when this article was first published, workers and youth were facing a stormy period on the political and industrial front.

The movement to the left in the Labour Party; the crisis within the British and world economy; the rise of Thatcher and the age of privatisation: all would serve to shatter the post-war consensus that had been so carefully built up by the capitalists and reformists alike.

Within this context, a study of the history of Labour in and out of government was vital in order to understand the turbulent processes taking place.

This assertion is just as true today as in 1976. With a Corbyn Labour government in sight, we need to understand how and why Labour moved left in the past. What are the lessons from this period for socialists today?

In June 1929, the general election resulted in a minority Labour government, under the premiership of Ramsay MacDonald and in the teeth of the beginning of the Great Depression.

Within two years, that government had been destroyed, with its leading members deserting to the open enemies of the movement and its parliamentary representation down to a shadow of its previous strength. This was a direct consequence of the non-socialist nature of the MacDonald government in dealing with the biggest economic crisis that capitalism had faced.

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was formed as a socialist grouping even before the birth of the Labour Party and participated in its founding. It provided a nesting ground for many of the worst, and a few of the better, Labour parliamentarians, while preserving, in a vague and diluted way, most of the socialist current in the Labour Party.

With the betrayal of MacDonaldism, the ILP at least could see this in political and not in personal terms. Thus John Paton, the general secretary of the ILP, said: “At bottom, their weak policies are an expression of the belief in political gradualism and therefore are unaffected by the votes they command in Parliament.”

The ILP’s newfound appraisal of the situation could have won it great political authority in the post-1931 Labour Party. Unfortunately, without any clear perspective, the ILP drifted into a split with the Labour Party at precisely the time that they could have exerted most influence; a split moreover that was posed in organisational rather than in sharply political terms.

The ostensible issue which led to disaffiliation of the ILP in 1932 was the question of Standing Orders, or parliamentary discipline for Labour MPs. The ILP would not accept that it could not vote against the leadership if necessary. The ILP rank-and-file were determined to have the ILP parliamentarians under their own control. Certainly far-reaching political principles lay behind the issue, but the argument was posed in purely organisational terms.

An organisational issue could only help to disguise the significance of the split, and the ILP, in disaffiliating on such an issue, were open to the allegations of being ‘splitters’ and ‘deserters’. This was often raised and made many honest rank-and-file Labour Party members see the ILP in this light.

As Trotsky commented, in surveying the outcome: “The ILP split at the wrong time and on the wrong issue.”

The confusion was compounded as the ILP drifted into disaffiliation without a clear conception of what their role should be and without any real preparation for the break by the leadership.

Ultra-leftism

In this rudderless situation, the Communist Party were able to influence the situation and push the vacillating ILP into an ultra-left direction. This cut it off from the main body of the movement at a time when a turn towards the Labour Party on a consistent socialist basis would have been highly fruitful.

Under the influence of its pro-Communist Party wing, the ILP voted in 1932 not only to disaffiliate from the Labour Party, but also to cut off relations with the Co-operatives; to demand that all members should cease work with the Labour Party; and, most lunatic of all, to opt out of paying the political levy to the Labour Party from the trade unions.

This meant complete abstention from the main current of the Labour movement. Fenner Brockway, then an ILP leader, later admitted:

“This swing to ‘ultra-leftism’ as a consequence of the failure of Labour Party parliamentarianism stands as a permanent warning against theoretical elaboration of revolutionary structure unrelated to the actual conditions of struggle.”

This ‘clean break’ policy was disastrous, not only for the ILP itself but, for a whole period, to the potentially fruitful developments in the Labour Party.

While the ILP for the next two years concerned itself with a fruitless attempt to find common ground with the Communist Party, and rapidly declined in the process, the Labour Party on the other hand, not only regained organisational strength but also, from the impact of events, a fresh resurgence of socialist attitudes. Far from being buried, the Labour Party was revitalised.

“Now some of the most silent accomplices of the previous regime had become raucous revolutionaries. MacDonald, Snowden and Thomas were to hang on a sour apple tree, while the cause of socialism marched to triumph.” (Michael Foot, Aneurin Bevan, vol. 1).

No longer fighting for crumbs

Not only did the Labour Party, by 1935, begin to retrieve the grave electoral reverses it had suffered but, however imperfectly, the profound concern felt by the broad layers of the British Labour movement at developments had filtered through to the Labour Party.

Not only did the Labour Party, by 1935, begin to retrieve the grave electoral reverses it had suffered but, however imperfectly, the profound concern felt by the broad layers of the British Labour movement at developments had filtered through to the Labour Party.

This left development and the Labour Party’s subsequent official policies were bound to attract leftward moving workers at such a period—a situation which the ILP did not bargain for and which hastened its demise, since it saw itself purely as a ‘competitor’ to the Labour Party at this stage.

Certainly there was a difference between the left-wing speeches and resolutions and actual activity. But this could not be fully brought to the forefront without a properly organised turn by the ILP towards the Labour Party.

In the event, what opposition there was, in an attempt to translate theory into practice at this time was provided by the Socialist League, which was mainly composed of intellectuals, and which after 1933 filled the void in the Labour Party left by the ILP.

At the very same time that the ILP walked out of the Labour Party Conference, the move to the left was shown. Thus Trevelyan introduced a resolution that said: “On assuming office, definite socialist legislation must be immediately promulgated and that the party shall stand or fall in the House of Commons on the principles in which it has faith.”

Clement Attlee seconded by making an implicit rejection of gradualism: “The events of last year have shown that no further progress can be made in seeking to get crumbs from the rich man’s table.” The resolution was carried without a vote.

The left-wing went even further at this time. Sir Stafford Cripps, in a pamphlet called, significantly enough, “Can Socialism Come By Constitutional Means?”, argued that it was utopian not to expect the ruling class to try by every means in their power (including all extra-parliamentary means) to stop the introduction of socialism and that the Labour movement must be prepared for it.

Ownership and control

Because of the pressure of the rank-and-file, the Labour leadership in its official programme had to move very far to the left in this period. This was shown in the publication of the NEC document For Socialism and Peace, in July 1934.

Because of the pressure of the rank-and-file, the Labour leadership in its official programme had to move very far to the left in this period. This was shown in the publication of the NEC document For Socialism and Peace, in July 1934.

In many ways, this was the most radical document in Labour history. With regard to “banking and credit, transport, water, coal, electricity, gas, agriculture, iron and steel, shipping, engineering, textiles, chemicals, insurance,” it said that “nothing short of immediate public ownership and control will be effective,” with workers having an “effective share in control and direction of industry.”

At this time, Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, was talking in terms of an “Enabling Act” through Parliament for taking over the commanding heights of the economy.

Certainly, however, there was an enormous disparity between words and real intentions. The Socialist League to some extent realised this and criticised it for not being explicit enough in terms of immediate objectives, and tying the leadership down to really concrete steps.

Moreover, it could afford to talk in terms of the policies of a future Labour government without outlining the steps to fight the existing National Government. However, it was an indication of the radicalisation of the Labour rank and file.

Tragically, the ILP had put itself into self-imposed exile, and in 1934 even rejected an invitation from the leadership of the Labour Party for a joint campaign…because it excluded the Communist Party. It considered relations with the flea as more important than with the elephant!

When the ILP did make a turn towards the Labour Party, together with the Communist Party and the Socialist League, it was not done on the basis of a socialist programme—but one that was to the right of the official Labour leadership.

One point, however, should be emphasised now. The massive electoral gains made by the Labour Party in the mid-1930s were direct consequences of its adopting, at least in words, the most left-wing programme in its history. That is a real lesson for today.

Popular Front

The Communist Party by 1935 had moved 180 degrees from its earlier ultra-leftism towards a position in which Stalin was seeking for accommodation on almost any terms with the “Western Democracies”.

The class position of the Communist Party and the independence of the Labour movement were to be subordinated to this. The ‘democratic status-quo’ was to be preserved, no explicitly socialist demands were to be raised, and an uncritical unity with capitalist parties was envisaged.

In Britain, the fruits of this were initiated with the so-called ‘Unity Campaign’ between the Communist Party, the ILP and the Socialist League (which represented the left of the Labour Party).

Theoretically the ILP opposed this new line; Maxton, its leader described it as an attempt to “subdue the class struggle”. However in practice and in the eyes of the labour movement, it subordinated its criticisms for the sake of an abstract ‘unity’ with the Communist Party. The consequences for a left-wing development in the Labour Party were disastrous.

At the initiating meeting of the ‘Popular Front’, as this line of alliance with the Liberal capitalists was called, at a platform line-up of a ‘progressive’ Tory MP, a Liberal and the Communists, the Liberal put the issue plainly:

“The basis of our unity as democrats against the menace of fascism in Germany and Italy must be a truce in the class war between workers and employers in this country.”

In reality, as experience in other countries shows, such an alliance on such a basis could only serve to deliver the working class up to fascist terror. A bold programme of socialist demands was necessary to strengthen the labour movement and bring into its orbit all the wavering elements in society. The experience of Spain was a tragic example of what was to happen when the Labour movement tied itself to the shirt-tails of ‘liberal’ capitalism.

Unity – but on what basis?

In theory, the ILP recognised this and would not tie itself in with an alliance with Liberals or ‘progressive Tories’. However, in practice the ‘Unity Campaign’, although just involving working class tendencies only raised demands which accepted the continuation of the capitalist system…when that system was in the greatest crisis of its history.

It sought to win the Labour Party to a programme far to the right of that which it accepted in words already. The result was a debacle. As Brockway was to admit:

“Its result was the destruction of the Socialist League, the loss of influence of Cripps, Bevan, Strauss and other ‘lefts’, the strengthening of the reactionary leaders, and the disillusionment of the rank and file.”

In practice then, the ILP and the Socialist League were dragged behind the ‘Popular Front’ line, with largely private reservations unknown to the ranks of the labour movement. They sacrificed themselves and their programme for an abstract ‘unity’.

The three groups issued a ‘Unity Manifesto’ in 1936 which almost exactly followed the ‘Popular Front’ line. The demands went no further than merely calling for the repeal of the 1927 Trades Dispute Act, higher pensions, opposition to unemployment assistance board scales, and self-determination for India, besides an uncritical approach to the Soviet Union and its “fight for peace” (which by this time merely meant Stalin’s diplomatic manoeuvres).

It was rejected out of hand by the Labour Party, who were swiftly able to bring the campaign to a halt, aided by the (private) antagonisms of the partners involved, by banning the Socialist League and threatening to expel any Labour Party member who appeared on a joint platform with the Communist Party. The Communist Party accepted the dissolution of the Socialist League as “a gesture for unity”.

The campaign was over in a matter of months, leaving behind not only a vastly weakened ILP but the debris of the only organised left in the Labour Party at that stage.

Shipwrecked

How was this made possible? In reality it was a classic case of how subordinating one’s political programme for the sake of papered-over unity can only spell disaster.

The ILP, with all its reservations, were seen in the eyes of the Labour movement as accepting an uncritical attitude to the bureaucracy of the Soviet Union at precisely the time when the Moscow purge trials of the old Bolsheviks unleashed a great wave of anger throughout the labour movement against Stalinism. This, in itself, severely compromised the campaign and gave the Labour leadership its opportunity.

In addition, by subordinating socialist objectives, the Labour leadership was able to attack the campaign from the left. Clement Attlee, the Labour leader, was able, with perfect ease to do this, drawing on the experience of the 1929-31 Labour Government:

“The plain fact is that a Socialist Party cannot hope to make a success of administering the capitalist system because it does not believe in it. This is the fundamental objection to all the proposals that are put forward for the formation of a popular Front in this country.” (Attlee, The Labour Party in Perspective)

The only way that a socialist group like the ILP could have won a decisive influence in the Party and the movement would have been a consistent turning towards the Labour Party on a Marxist programme. This could have raised the day-to-day issues and linked them to the need for the socialist transformation of society. In this way, the verbal ‘leftism’ of the official Labour leadership would have been put to the test.

Failure to do this, and subordination to Stalinism, meant shipwreck for the ILP (which had the support of 100,000 workers in 1932) and the failure of the Socialist League.

The turn towards imperialist re-armament and eventually coalition government by the Labour leadership in the late 1930s, can be explained not only by the defeats suffered by the movement internationally (as in Spain) but also specifically in light of this failure of the ILP.

Break with capitalism

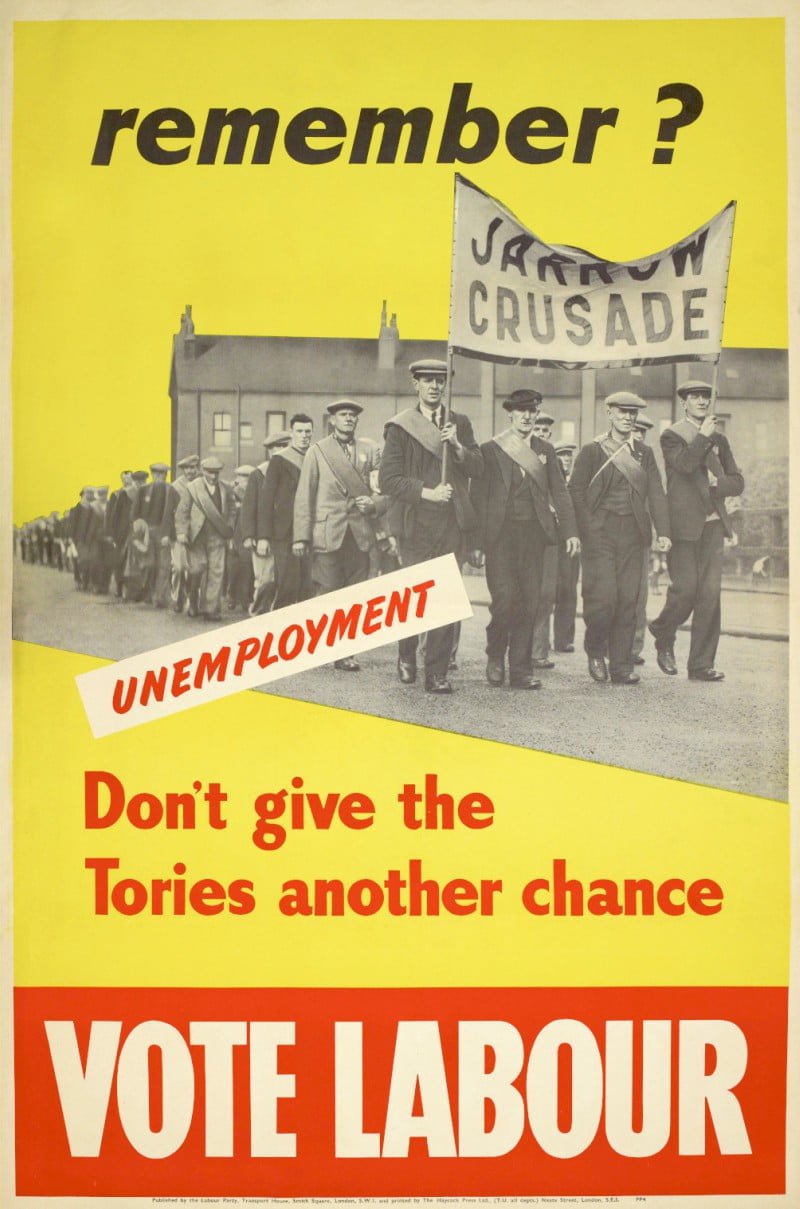

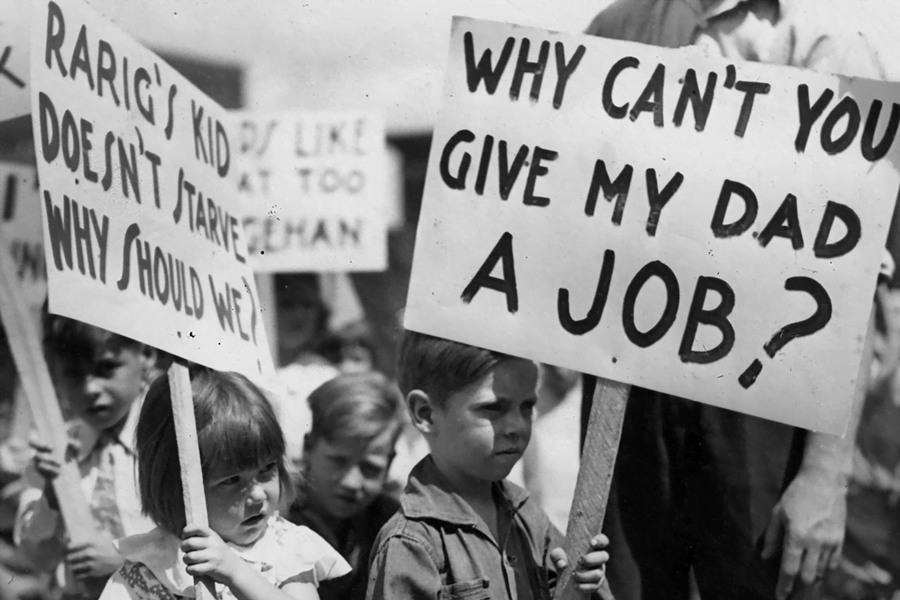

The long post-war boom period has drawn to its close. Mass unemployment again, as in the 1930s, is a menace for the working class.

The long post-war boom period has drawn to its close. Mass unemployment again, as in the 1930s, is a menace for the working class.

The failure of the capitalist system, and the failure of the present Labour leadership to meet the needs of the situation in the interests of the movement, is provoking the development of a left wing. As in the pre-war period, this is beginning to demand socialist solutions. Only by absorbing the lessons of past failures can this movement go on to future success.

There is one important difference, however, from the 1930s. The working class has emerged from the post-war boom immeasurably strengthened and better organised. It has not suffered a serious defeat, unlike its predecessors in the dark inter-war years. Internationally, we can have a confident perspective of working class victories, rather than the bloody victories of fascism.

In his book Inside the Left, Fenner Brockway, one of the leaders of the ILP, reflected that “when the ILP was in the Labour Party it had no fundamental philosophy or policy and could not act with united purpose.” He admitted that the left-wing opposition to the right-wing Labour leaders in 1932 consisted merely of a “mixture of reformism, sentiment, utopianism and awakening revolutionism.”

Thus the leaders of the ILP failed in the duty to galvanise a mass left wing, armed politically with a socialist programme, organised in opposition to the Labour leaders and working along a clear perspective rather than reacting blindly to events.

As in the 1930s, in the coming period of class conflicts the Labour Party will be the key area of political struggle. Armed with a Marxist programme and perspective, and based on the mobilised mass movement, the left can overcome the pitfalls and disasters of the 1930s and lead the working class to a successful break with capitalism.