Unprecedented levels of cuts have ravaged local councils for over a decade now. Half a million council workers have lost their jobs since 2010. Council budgets have shrunk by 77% as the Tory government in Westminster has cut funding year on year.

Libraries, special educational needs services, and Sure Start centres have all been closed. In 2019 more than a quarter of councils said they expected by 2022 to be unable to meet their legal obligations to deliver statutory services such as social care, educational services, waste collection and children’s safeguarding.

The cuts bankrupted Northamptonshire County Council in 2018, and Croydon Council last year. Dozens more are on the cliff edge.

The situation has now worsened dramatically, as councils have had to bear the brunt of dealing with the social crisis caused by the pandemic. This includes essential tasks such as delivering food parcels to the vulnerable, funding care homes, and finding housing for rough sleepers and those fleeing domestic abuse.

Thanks to the Tory government councillors are now faced with having to slash services to the bone to recover the costs. This would amount to making working class people pay for the pandemic.

But this isn’t the only option. The lessons from the Poplar Rates Rebellion, which took place 100 years ago in East London are more relevant today than ever. We can fight and win against a decade of Tory austerity, and this attempt to make the working class pay for the pandemic.

Background

Poplar’s Labour council was elected in 1919 against the backdrop of an international revolutionary wave.

The horrors of the First World War ended in the revolutions in Russia and Germany in 1917-18. Rebellion in Ireland and revolution in Europe led the British capitalists to look nervously at their own working class.

A number of concessions were granted, such as the Representation of the People Act, that effectively ended the property qualification for voting and granted female suffrage, though only for women aged 28 and over.

In 1919, the Labour Party gained 39 of the 42 Poplar council seats. This was achieved despite a vicious, pro-business opposition that accused the LP of having a policy of workers’ control which would mean “anarchy and starvation, industry destroyed, religion swept away, women nationalised and enslaved”, (East London Advertiser, 1 March 1919).

Across London, Labour went from having 46 of the 1,362 borough councillors in 1912 to 572 in 1919.

The Poplar councillors undertook a number of important social reforms, including equal pay for women; the building of houses, parks and wash houses; the distribution of free milk; and a minimum wage for council workers above the national average.

As opposed to the previous administration’s prescribed ‘Christian Salvation’, the newly elected Labour council undertook a survey and recommended a huge acceleration of slum clearances. They appointed three new sanitary inspectors who would order slum landlords to carry out improvements.

This was a significant reform for Poplar, which was rife with tuberculosis. Infant mortality was also present, with one in eight babies before the war not surviving their infancy.

Rebellion

Poplar Borough Council was obliged to contribute to London-wide bodies such as the London County Council (LCC), Metropolitan Asylum Board (MAB), the Metropolitan Water Board and the Metropolitan Police. This impacted disproportionately on the poorer boroughs, which were required to pay the same fixed rate as the richer boroughs of West London.

In addition to the citywide contributions, individual London boroughs were expected to raise their own poor relief. The West London boroughs had just 5,000 poor to support, as opposed to the 86,500 of East London.

At the beginning of 1921, faced with a further increase in the citywide rates of between 25-50%, Poplar Labour councillors decided that enough was enough. They agreed to consult the labour movement as to what should be done about the unfair rates system.

A conference of Labour Party and trade union branches was called where George Lansbury, leader of the Poplar Labour councillors, proposed that the council stop collecting the rates for cross-London bodies. The proposal was voted through, and on 31 March the council set a rate of 4 shillings and 4 pence, instead of the 6 shillings and 10 pence necessary to cover the rates.

The councillors immediately set about acting on their decision. They had consulted the labour movement and drawn up a new rates policy. Now it was essential to make sure their action was carried to the people of Poplar.

They drew up a statement, sent to every member of the borough, explaining the reasons behind the council’s decision. The key demand was ‘equalise the rates’. In essence, the council had called a rent strike, importing industrial action into the arena of municipal politics.

On 28 May, the first instalment to the LCC was due. The council resolved to continue its stand. In response the LCC took the matter to the High Court. Once the courts, judges and the state came into question, a clear differentiation took place within the labour movement.

On the right wing stood the ‘constitutionalists’ – headed by the Mayor of Hackney and London LP leader Herbert Morrison – who were desperate to confine the class struggle to within the boundaries of respectability and the law.

On the left were the Poplar councillors, headed by George Lansbury, whose position was:

“It is well that organised labour should understand that in the courts of law all the scales are weighted against us because all the judges administer class-made laws, laws which are expressly enacted not to do justice but to preserve the present social order.”

George Lansbury and the councillors spoke to a crowd of supporters on the morning of their court appearance outside the Poplar town hall . “If we have to choose,” said Lansbury, “between contempt of the poor and contempt of court, it will be contempt of court.”

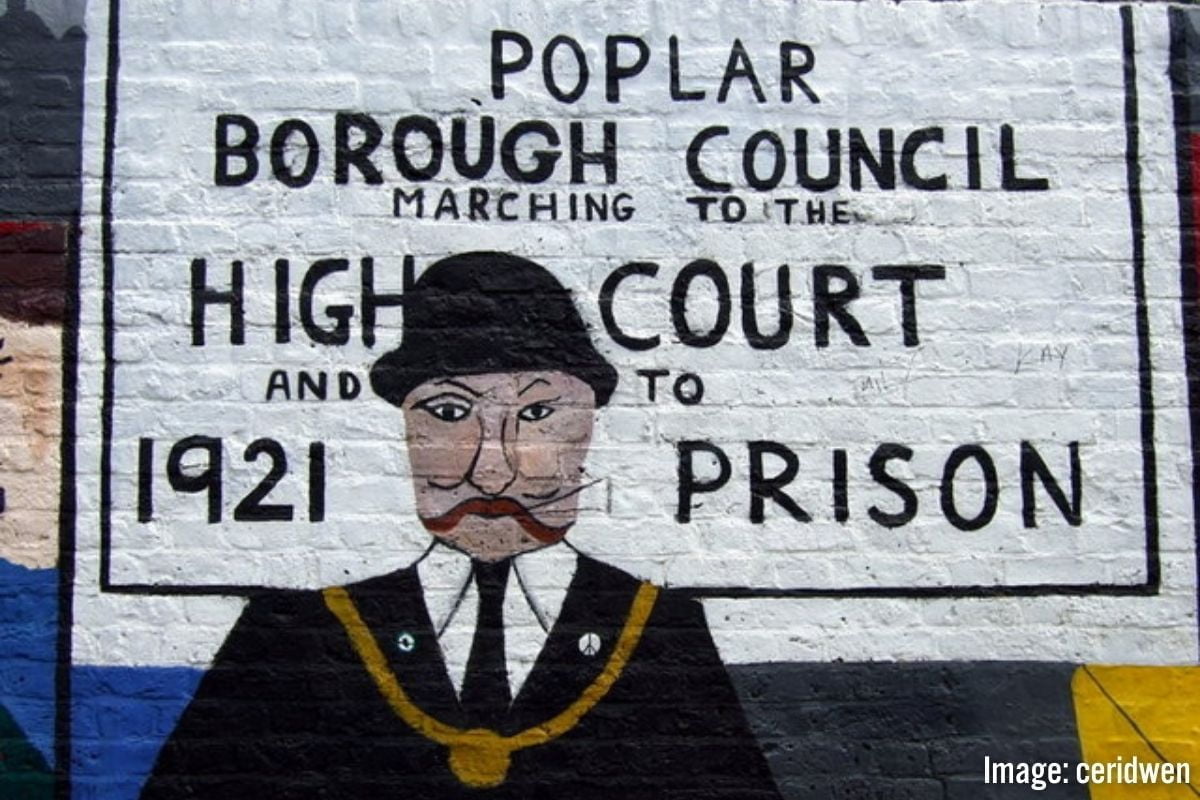

After this, a 2,000-strong march began, from Bow to the High Court. They marched the five miles under the banner: “Poplar Borough Council, marching to the High Court, and possibly to prison.”

The High Court found against the councillors, giving them 14 days to pay up or go to prison. Resolved to face prison, the councillors used this time to organise. They again wrote to all ratepayers and organised mass meetings to explain the situation.

The Poplar Trades Council sent a circular to all the London trades councils asking them to put pressure on their local Labour councils to support the Poplar councillors.

Opposed to this, Herbert Morrison, fearing accusations of ‘irresponsibility’ and ‘Bolshevism’, drafted a circular asking all LP branches and all trades councils to repudiate Poplar’s actions. Their aim was to effectively leave Poplar isolated.

Prison

Huge crowds of supporters, accompanied by trade union banners, met the councillors as they were arrested at their homes.

Thirty councillors, including six women (one of whom was pregnant), were sent to prison indefinitely for refusing a court order to pay the rates. They issued a statement from prison:

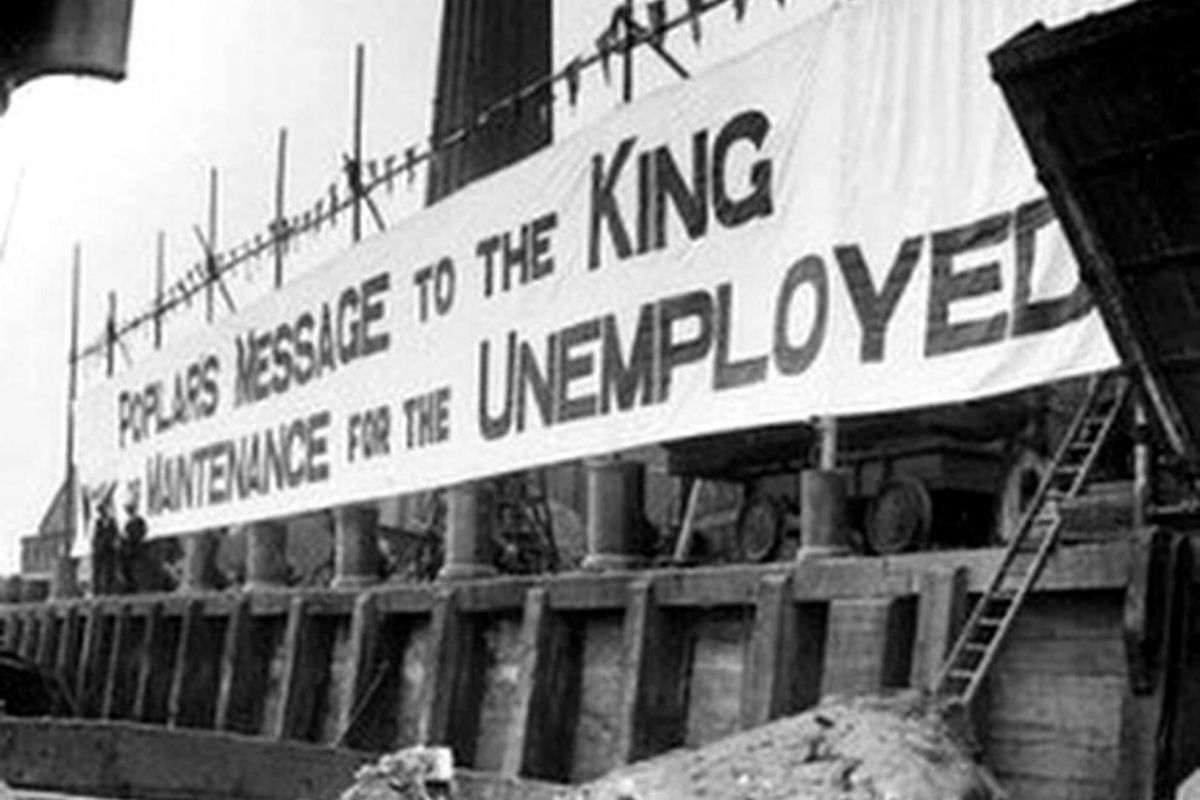

“Thirty of us, members of the Poplar borough council, have been committed to prison. This has been done because we have refused to levy a rate on the people of our borough to meet the demand of the LCC and other central authorities. We have taken this action deliberately and we shall continue to take the same course until the government deals properly with the question of unemployment, providing work or full maintenance for all, and carries into effect the long-promised and much overdue reform of the equalisation of rates.”

Through his cell bars, George Lansbury would daily address mass meetings outside the prison. Demonstrations were held every weekend in East London to keep the movement in the public eye.

Thousands rallied in support in Trafalgar Square on 10 September. With unemployment rising throughout the country, the actions of Poplar were accompanied by unemployment riots in cities like Dundee and Liverpool. Mass meetings of the unemployed were being held throughout London in August and September, giving the struggle in Poplar particular focus.

The ruling class was feeling the hot breath of revolution on its neck and looked for a way out. Dismissing the councillors would add fire to the flames. In any case, new elections would see new councillors elected with the same position; such was the mood in society.

Even the threat of withdrawal of citywide services like the police were rendered impotent, as Poplar had secured a promise from the Police and Prison Officers Union that in such an eventuality, they would supply the borough with a ‘trade union police force’, drawing the average workers wage!

As the imprisonment continued, the struggle spread. Neighbouring boroughs Bethnal Green and Stepney also withheld the rates. By showing other LP councillors backbone and resolve, Poplar was able to elicit, through example, solidarity actions. This ultimately rested on the wide, rank-and-file popular support for the councillors’ actions.

Stepney Trades and Labour Council protested the anti-Poplar position of Herbert Morrison and the right-wing leadership of the London Labour Party. On some councils, LP right-wingers ‘crossed the floor’ to vote with the opposition to defeat what should have been a LP majority. This shows how a crisis puts all currents and tendencies within the labour movement to the test.

Support

After six weeks’ imprisonment, the government backed down to the widespread support that had been unleashed by the councillors’ stance. The High Court ordered the prisoners to be released.

At the same time The London Authorities (Financial Provision) Act 1921 was rushed through Parliament, which although not completely equalising the rates, was nevertheless a major victory.

Sir Alfred Mond, the Health Minister, recommended the government’s terms of surrender: a four-fold increase in the equalisation rate and a doubling of the allowance for workhouse inmates. The effects were that the eight richest London boroughs would pay £800,000 per year instead of £400,000, to the benefit of the poorer boroughs.

The lesson of the Poplar rebel councillors is an inspiration to labour movement activists today.

Lobbying the bosses for concessions had only got the working class to a certain point, after which it could proceed no further without clashing with the ruling class in the form of its state, laws, and apparatus. It was only when the Poplar councillors took the lead of a mass movement that reforms were wrested from the ruling class.

When we compare the stance of Lansbury and Morrison (incidentally the grandfather of Peter Mandelson), the question arises: who are our councillors responsible to?

Morrison wanted to prove his responsibility to the establishment, so-called ‘respectable society’, from whom he so cravenly sought approval. Lansbury and the Poplar councillors understood they were responsible solely to the toiling poor of Poplar and the wider working class.

The Poplar councillors fully understood the class nature of the courts and the laws. This is why they did not defer to them, but stood up and defeated them with the backing of a mass movement of the working class.

Today

A militant, uncompromising struggle against the attacks on council budgets is what is needed today. The alternative is a devastating assault on the living conditions of millions of people.

When Croydon council went bankrupt last year, this Labour council announced that libraries and children’s centres would be closed, in a move they admitted would impair the development of children from the poorest households. Already, 30% of children in Croydon are living in poverty.

Underage asylum seekers under the care of the council are set to be moved on. Elsewhere, the welfare benefits advice team is due to be scaled back – despite experiencing a 300% increase in demand since the beginning of the pandemic.

Leisure centres and recycling facilities are to be closed. And further job losses are on the cards, on top of the 400 positions axed earlier that year.

Without a serious fightback, local authority workers are facing intolerable cuts to their working conditions. Last year in Tower Hamlets, a Labour council used fire-and-rehire tactics to introduce an outrageous new contract attacking workers.

The new contract cuts down a range of allowances, slashes severance, reduces the current flexi-scheme, and extends some grades backwards, to name but a few of the detrimental changes.

This vicious attack came after years of austerity. Local councils have already suffered from massive underfunding, and public sector workers have seen an approximate 25% reduction in real wages.

It is an appalling scandal that today’s Labour councillors are implementing these Tory cuts, hiding behind Tory laws and capitalist courts to claim they don’t have a choice.

For working class people cuts are cuts. Whether they are carried out by Tory or Labour councillors doesn’t make a difference when you’re slipping further into poverty.

This goes some way to explaining the haemorrhaging of votes in traditional Labour areas, such as Hartlepool and the rest of the ‘Red Wall’. People’s lives are getting worse in these areas, which have been presided over by Labour councils for decades.

The Labour leaders correctly point out that this is because of Tory cuts. But pointing it out is not enough. People ask: ‘Yes but what are you going to do about it?’ If the answer is that there’s nothing Labour councils can do, then people will begin to wonder why they should bother voting Labour at all.

Poplar shows us that something can be done. This is the lesson Labour leaders and councillors need to understand.

Leadership

It’s quite clear that Keir Starmer has no interest in fighting the government, on council cuts or anything else.

Starmer wants an accommodation with the Tories and is willing to sacrifice the livelihoods of millions of working class people to get it. His support base in the Labour Party is those people who sabotaged Labour at the last two elections, preferring this Tory government to a Corbyn-led Labour one.

Starmer needs to be removed as Labour leader, and the rest of the Labour right wing need to be driven out of the Labour Party. They’re a direct obstacle to the fight to defend working-class people against the Tories. This is the first necessary step towards a new Poplarism.

And the trade unions need to organise a concerted and vigorous mass campaign against the cuts. In Tower Hamlets, Unison balloted for strike action against the new contracts. Over 90% of workers supported the strike.

In Norwich, Unison and Unite council workers have recently taken strike action after being forced onto worse contracts.

The recent sweeping victory for the left in the Unison NEC elections, also gives an indication of the radical mood among public sector workers.

This mood needs to be harnessed by the unions and turned into a mass campaign of industrial action. Combined with an effort to remove the right-wing dead-weight in the Labour Party, this could unleash a mighty struggle against the government around defending local councils and the working-class people they serve.

Lessons

In the 1980s, Liverpool faced sharp cuts from the Thatcher government. Furthermore, the city was dealing with long-term deprivation that had been ignored by the previous Liberal administration, which ruled with Tory support.

In response, the Labour council decided to launch a mass campaign for the resources it needed to tackle the city’s problems.

This included launching the Urban Regeneration Strategy, which built 4,800 council houses, amongst other achievements. Back then, regeneration was properly planned, and not left to private developers.

Councillors drew up what would now be called a ‘needs budget’ of expenditure. At the same time, the council refused to raise rates – the forerunner of the council tax – above inflation, rightfully arguing that this would be a wage cut.

The gap between the money needed and that coming in from grants plus rates was £30 million. The demand for this amount was the centre of the campaign.

The city council then gained mass support, increasing the Labour vote by 40-80% in elections in the 1980’s.

If such a militant approach was taken today the Tories would undoubtedly fight back using all the methods at their disposal. This would include sending in unelected commissioners to take over the running of the council.

Such commissioners would take their orders directly from the Tory government, pushing an agenda of cuts and privatisations. This has been done in Liverpool this year, scandalously with the support of Starmer himself!

But a mass campaign of industrial and political struggle would blow these commissioners out of the water.

In the early 1970s, Clay Cross council refused to implement cuts, so the government sent in commissioners. But these bureaucrats were completely unable to carry out their jobs because the entire council workforce went on strike as part of the campaign against the cuts. They couldn’t even find anyone to make them a cup of tea!

We must study the lessons of Poplar 100 years ago and use them as inspiration for developing a fighting strategy in the labour movement today. Lansbury and the Poplar councillors proved that a radical programme and a serious fightback are what really improves the lives of working class people. It’s our task to develop this today.