26 August marked the 110-year anniversary of the beginning of the Dublin Lockout, one of the most significant events in Irish labour history.

In this dispute, 20,000 members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) and their 80,000 dependents battled with the forces of Irish capitalism led by William Martin Murphy.

At this time, the labour movement in Ireland was extremely young. The ITGWU was the first mass union in the country. And from its birth, it was immediately thrust into a desperate struggle for survival.

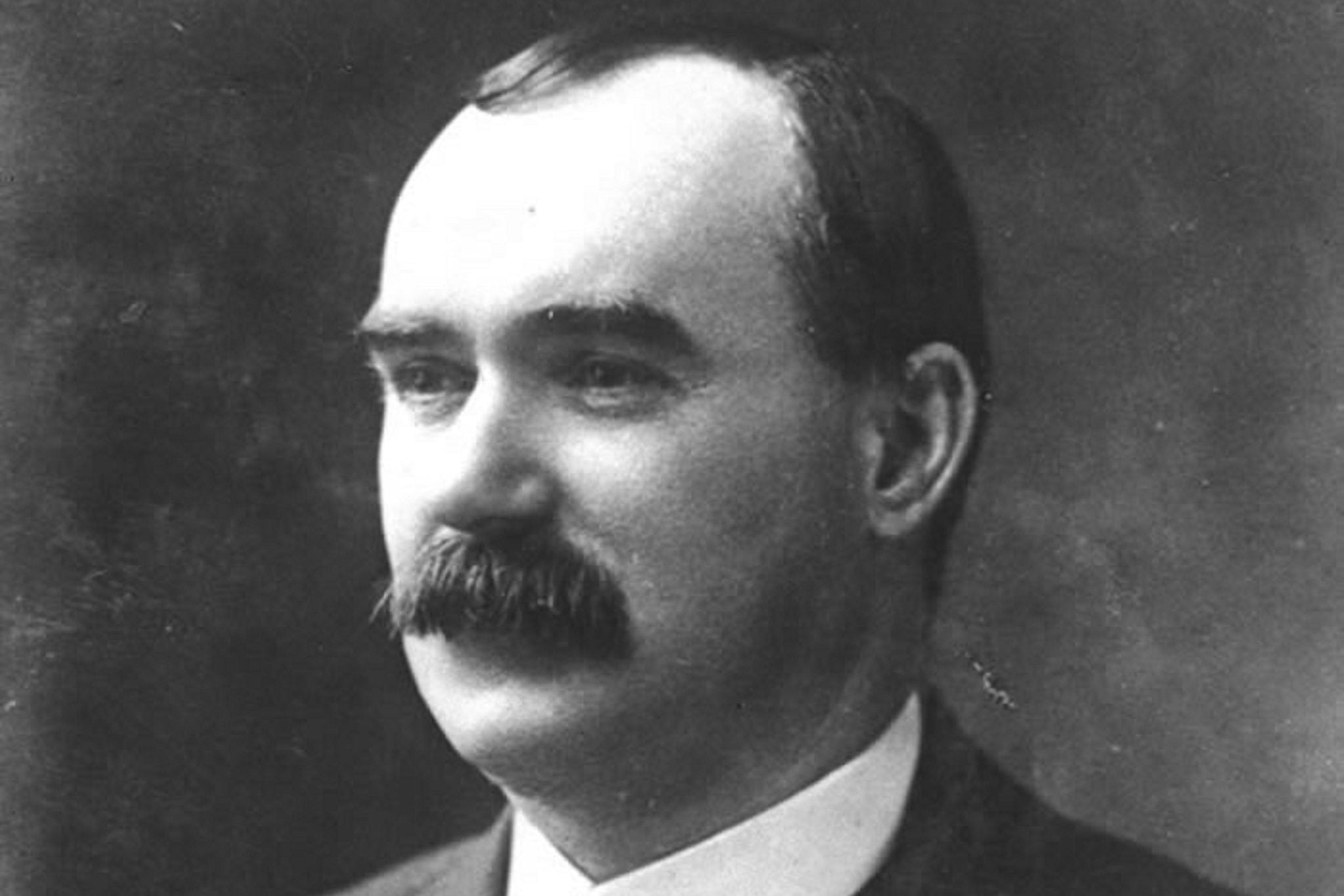

But under the revolutionary leadership of James Connolly and Jim Larkin, Irish workers were to leap far over the heads of the more established trade unions across the sea.

The workers were conscious that this was a life-or-death struggle for the very existence of their organisations. They made use of advanced tactics – such as the sympathetic strike – and the formation of a workers’ militia, the Irish Citizen Army, to defend against the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) and scabs. This would later play a pivotal role in the Easter Rising in 1916.

The dispute ended, however, with a stalemate, in which the working class returned to work in January 1914 – exhausted, but with its organisations intact.

The recent strike waves that have taken place in Britain and Northern Ireland show the absolute necessity of not only commemorating these struggles, but learning from them.

Foundation of the ITGWU

The reformists in the labour movement today will present revolutionary Marxism as an alien force. But the truth is that Ireland’s first trade union – the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) – was built by open, committed Marxists: Jim Larkin and James Connolly.

The union was founded in 1909. And workers in Dublin, where working conditions and pay were wretched, even compared to the poor conditions of English workers, quickly flocked to join.

For decades, the British and Irish capitalists had been whipping up sectarianism and Orange reaction in order to divide the working class. Nevertheless, the ITGWU was able to unionise both Catholic and Protestant workers.

In fact, Larkin’s first breakthrough in Ireland, under the National Union of Dock Labourers, which led to the formation of the ITGWU’s formation, was precisely in the Belfast docks in 1907.

Class struggle again erupted in Belfast in 1911, under Connolly’s leadership, with a strike of 1,500 women – the ‘linen slaves’ of the textile sweatshops – that won major concessions.

But by 1913, it was Dublin that was emerging as the centre of the ITGWU’s organising. And the Irish bosses were determined to deliver a deadly blow.

Just as the workers recognised that their main enemy was the bosses, the Irish and English capitalists also found sudden solidarity in their burning desire to crush this dangerous new organisation before it could get any stronger.

Lockout begins

In an attempt to curb the further development of the ITGWU, William Martin Murphy – a former nationalist MP and major capitalist who owned the Irish Independent – and the Dublin Employers’ Federation attempted to sack around 400 known union members from the city’s transport industry.

This was an intimidation tactic as old as time – one that is still being replicated today by corporations such as Amazon.

The Dublin bosses organised coordinated action to break the union. Workers arrived in the morning to find the gates of their workplaces locked. They were told that they would not be working or receiving pay unless they agreed to renounce their membership of the ITGWU and their right to strike.

Far from being cowed, under the leadership of Connolly and Larkin, the workers went on the offensive. All ITGWU members were called out on strike, and solidarity campaigns were set in motion amongst other organised workers, such as the United Building Labourers Union (UBLU).

Enormous solidarity was also forthcoming from British workers. In Manchester, 25,000 workers gathered to hear Connolly and Larkin speak about the struggle. At the decisive moment, class instincts cut across seemingly deep cultural and national divides.

Heroic struggle

For seven months, the strikers carried out a heroic struggle against all the odds. The bosses tried to crush the strike by bringing in blackleg labour from Britain. Strikers used mass pickets to stop scab labour.

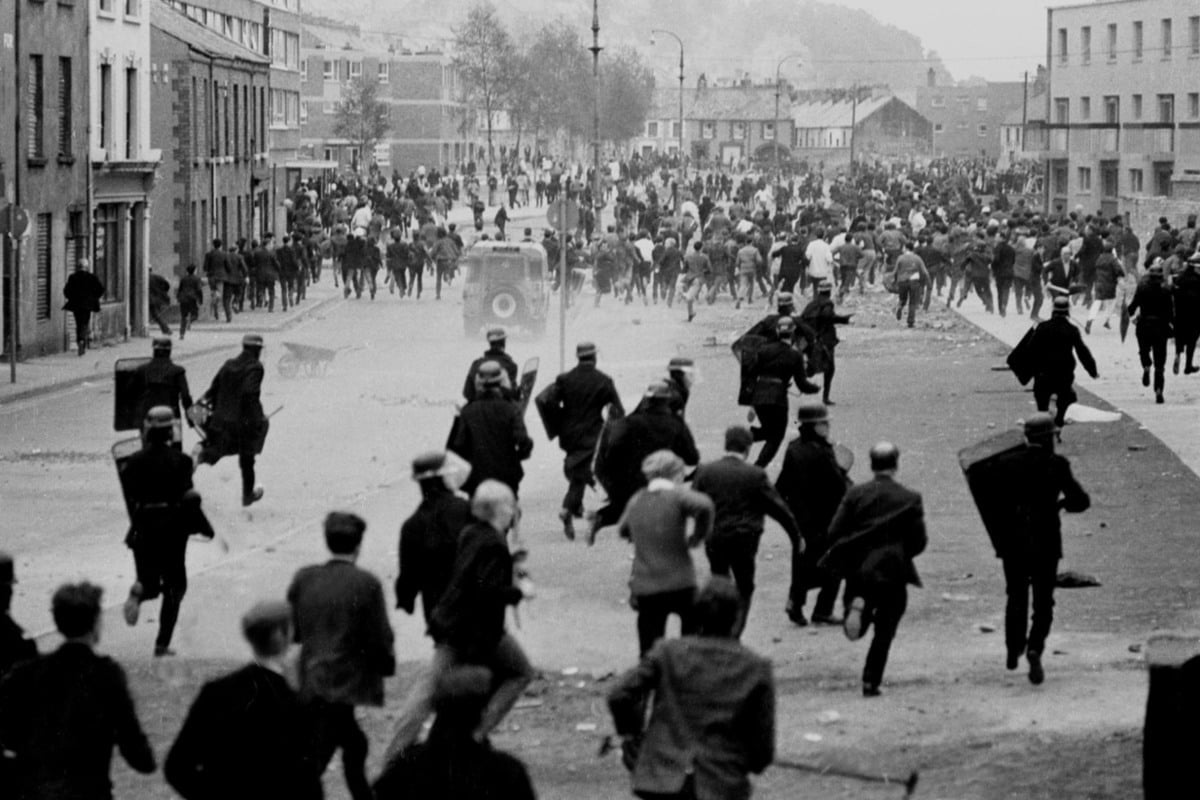

The state did everything they could to assist the employers. Perhaps the most egregious brutality was carried out on 31 August, or ‘Bloody Sunday’, when the Dublin police carried out a baton charge against workers in order to break up a meeting at which Jim Larkin was speaking. Two workers were killed and 300 injured.

“The police have positively gone wild,” wrote Lenin at the time. “Drunken policemen assault peaceful workers, break into houses, torment the aged, women and children…People are thrown into prison for making the most peaceful speeches. The city is like an armed camp.”

One worker, Alice Brady, was shot dead as she brought home a food parcel from the union office. Another union organiser was tortured to death in a police cell.

In order to defend the strike from the police, Connolly, Larkin, and co. founded the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) – a volunteer organisation made up of union workers.

In practice, this was a workers’ militia based on the trade unions; Europe’s first Red Army. They drilled openly and practised in the streets. This showed just how far consciousness had developed in the course of the strike.

The ICA would go on to play an instrumental role in the Easter Rising, as the most militant, proletarian element in the Republican movement at the time.

Betrayals

Despite this heroism, the Dublin workers were met with betrayal from all angles. The Irish national movement divided along class lines.

While the best revolutionary Republicans like Countess Markievicz and Padraig Pearse drew close to Connolly and the ITGWU, the Irish Parliamentary Party enthusiastically supported the bosses.

Sinn Féin’s Arthur Griffith, meanwhile, poured scorn on striking workers, accusing them of undermining Irish industry in Great Britain’s favour.

An even more reactionary role was played by the Catholic Church. When the ‘Dublin kiddies’ scheme was organised to house the starving children of locked out workers with working-class families in England, the clergy did everything to prevent these children from being fed by the ‘godless’ British working class. Catholic clergy even organised ‘vigilance’ committees in Dublin and Dún Laoghaire in order to prevent children leaving the city!

None of this came as a surprise to Connolly, who understood that the labour question was always primary. No amount of national or religious feeling would convince the bosses and clergymen to have compassion for the working class.

Connolly did understand, however, that if the strike was to succeed it would need international working-class solidarity – especially from Britain.

From the outset, the struggle of Dublin’s workers was undermined by the use of scab labour, usually brought over from Britain. Had the British trade union leadership acted decisively, they could have stopped this dead in its tracks, calling on workers to refuse to transport any scabs or handle any goods produced by scab labour.

Connolly recognised this, and called on the union leaders to escalate their support for the dispute.

Despite the enthusiasm of English rank-and-file workers for solidarity action, calls to extend the strike to Liverpool, Glasgow, and elsewhere fell on deaf ears in the British trade union bureaucracy. They refused to commit anything to assist the Dublin workers.

In a particularly despicable act of betrayal, the Seaman and Fireman’s Union threatened any Belfast workers who refused to open the shipping lines to the flow of scab labour with replacement!

Connolly explained that the Dublin lockout was “sacrificed in the interests of sectional officialdom”.

In the decades preceding the First World War, the British labour leadership had come to enjoy vast privileges that detached them completely from their membership.

The British Labour Party began to enter Parliament in large numbers in the first few years of the 20th century. This gave labour politicians the opportunity to fraternise with the bourgeois establishment. In these conditions, these labour leaders saw the Irish movement as little more than embarrassingly poor cousins.

Connolly explained: “We asked for the isolation of the capitalists of Dublin, and for answer the leaders of the British labour movement proceeded calmly to isolate the working class of Dublin.”

Reform or revolution?

The narrow outlook of the British trade union leadership was miles apart from the revolutionary leadership of Connolly and Larkin.

The potential for a far greater solidarity movement was proved many times during the Lockout. British workers organised £150,000 in support of Dublin’s workers, for example. But this clear, class-based outlook found no expression amongst the reformist leadership.

“Had working-class officialdom and working-class rank and file alike responded to the call of inspiration,” Connolly explained, “it would have raised us all upward and onward towards our common emancipation.”

What this showed was the need for revolutionary leadership in the labour movement. This is just as true today.

Many workers recently engaged in strike action have been understandably frustrated by their leadership’s unwillingness to escalate and coordinate strikes.

As the recent dispute in healthcare – involving the RCN, BMA, and Unison – showed, the British labour leadership today will barely coordinate strike action between two unions working in the same hospital, let alone think of international solidarity!

It is therefore necessary for us to draw from the example of Connolly and Larkin, and redouble our efforts to build a revolutionary leadership in the labour movement.