The Great Unrest is the term used by historians to describe

the period a 100 years ago when

Britain saw many industrial conflicts such as the Cambrian Combine Strike, the

Tonypandy Riots and many other struggles.

In Wales there was also a major dispute in the Cynon Valley and riots in

Llanelli during the Railwaymen’s strike. Strikes occurred in Clydeside, London,

Liverpool, Hull and many other towns and cities throughout the land. Important ideas were developed

and discussed during this period which had a profound affect on the Labour and

trade union movement.

Darrall Cozens, a member of the UCU and Coventry NW Labour

Party, considers what we need to learn from these events.

The Great Unrest is the term used by historians to describe

the period a 100 years ago when

Britain saw many industrial conflicts such as the Cambrian Combine Strike, the

Tonypandy Riots and many other struggles.

In Wales there was also a major dispute in the Cynon Valley and riots in

Llanelli during the Railwaymen’s strike. Strikes occurred in Clydeside, London,

Liverpool, Hull and many other towns and cities throughout the land. Important ideas were developed

and discussed during this period which had a profound affect on the Labour and

trade union movement.

Darrall Cozens, a member of the UCU and Coventry NW Labour

Party, considers what we need to learn from these events.

On August 16th 2011, in what was for the BBC an unusually

unbiased programme, the newscaster Huw Edwards reported on the 100th

anniversary of the shooting dead of two young men by the British Army on the

mainland of Britain.

John ‘Jac’ John, a tinplate worker, had joined a picket line of

railway workers who were on strike in protest at average wages of £1 per

week, which were about 20% below the average wage paid to skilled

manual workers. The strike had begun on August 17th and was being

supported by local miners and tinplate workers who were on much better

wages.

The younger man to die that day was Leonard Worsell from London who

had come down to Llanelli to recover from TB. He had been shaving in the

kitchen of a house overlooking the railway line when he became aware of

something happening and had gone out into the back garden to have a

look.

Some 500 strikers and their supporters had blockaded two

level crossings in the town of Llanelli stopping trains from passing through.

At the time the GWR line through Carmarthenshire was the main route for

ferrying troops to and from Fishguard and then Ireland, where battles were being

fought against the occupation of the country by British Imperialism.

As Huw Edwards said, “While union leaders were negotiating

inside the town hall, troops from the Worcestershire Regiment bayonet-charged

the crowd in order to clear the line for a passenger train. The locomotive made

it through the first level crossing, strikers pursued it, clambering aboard,

raking out the fire and rendering the train immobile. Troops followed on the

strikers’ heels but soon realised that they’d trapped themselves in a cutting,

surrounded by stone-throwing strikers on the banks all around them. Major

Brownlow Stuart ordered the soldiers of the Worcester Regiment to open fire.”

Two workers lay dead.

Yet what happened in Llanelli was not an isolated incident.

Up and down the country, in the years leading up to World War One, as workers

took action to defend and improve their living standards, they were being

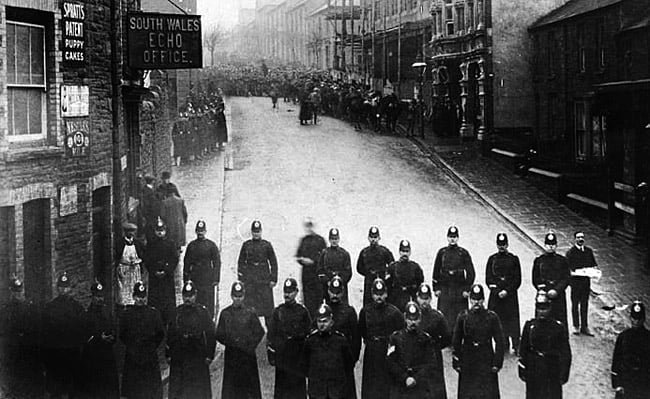

injured and killed by forces of the state. In Tonypandy one striker was shot

dead and around 500 injured in November 1910. In September the same year miners

on strike in South Wales had fought pitched battles against troops, the police

and scabs. Seamen in Southampton came out on strike over wages and this spread

to other ports with dockers and carters joining in. Even places that were not

unionised took up the fight. In Hull some 15,000 dockers threatened to burn the

docks down.

In Liverpool a railway strike escalated into a generalised

transport strike. Two warships were sent up the Mersey and armed troops broke

up a demonstration of 80,000 workers. Two were shot dead. What was significant about the

Liverpool strike was the working class unity between Protestant and

Catholic mainly Irish workers. London too was not

immune as it was under virtual martial law occupied by thousands of troops.

Workers showed in action that they were prepared to take on the

“bodies of armed men” whose task it was to defend the state. And the

task of the state was to defend British capitalism whose dominant

position on the world stage was coming to an end and with it the era of

reforms.

Background.

In the period leading up to the Great Unrest of 1911 to 1913

a number of factors came into play; the steady economic decline of the UK on

the world stage; the growing division of wealth; the steady fall in the real

value of wages; the growth of trade unionism and trade union membership as well

as militancy; and the attacks on the working class by the state.

In the 1870s, Britain was the dominant capitalist economy on

the world stage. By 1913 she had been overtaken by the USA and Germany. This

was not only the case for general manufacturing production but also for its

constituent parts:

Percentage Distribution of the World’s Manufacturing

Production 1870 and 1913

(% of world total)

1870 1913

USA

23.3 35.8

Germany 13.2 15.7

U.K

31.8 14.0

France 10.3 6.4

Russia 3.7 5.5

In all areas the world domination of Britain was being challenged by

emerging capitalist economies. As that challenge intensified Britain

found it harder to compete in the area of trade of manufactured goods.

This was not surprising given that apart from a few years at the end of

the 19th century, the amount of capital equipment per worker in Britain

remained constant between 1870 and 1913, while in Germany and the USA it

was rising fast. To compensate, Britain developed its banking and

finance sector as well as overseas investments so that invisible

imports from the repatriation of profits began to make up for the

decline in visible exports. For example, India alone financed two-fifths

of Britain’s balance of payments deficit.

In 1913, Britain owned about £4bn worth of capital invested

abroad compared to £5.5bn owned by the USA, Germany, France, Belgium and

Holland put together. In financial terms Britain was still the dominant

economic power. The earnings from the rising stock of British assets abroad was

£35m in 1870 or about 13% of total industrial and financial profits. By 1913

earnings were £200m, more than one third of total profits. Furthermore, another

£168m of profit came from shipping and financial services in trade, banking and

insurance. The finance sector of British capitalism was far more interested in

short term profits from overseas than in investing in UK manufacturing to

maintain its competitiveness. In fact in all areas of production Britain was

slipping further and further behind.

“Britain also increased its dependence on imported goods

following the introduction of free trade. From 1883 to 1913 the Sterling value

of her imports rose by 84%. The real effect of the shift to import dependence

was obscured by this phenomenal success of earnings from invisibles. In 1860

Britain led the world in coal production, the raw material feeding her industry

and fuelling her navy, with almost 60% of the total. By 1912 that fell to 24%.

Similarly, in 1870 England enjoyed an impressive 49% share of total world iron

forging output. By 1912 it was 12%. Copper consumption, an essential component

of the emerging electrification transformation, went from 32% of world

consumption in 1889 to 13% by 1913” (Oil and the origins of the war – Engdahl)

The economic success of Britain from the 1850s onwards,

based mainly upon the rape of its colonies as the British Empire expanded,

enabled the capitalist class to make some concessions to an increasingly

organised working class. Reforms in the franchise and increased wages for

skilled workers led to the emergence of an aristocracy of labour, a relatively

privileged layer of workers who rose above the general level of poverty that

afflicted so many sections of the working class.

Even within the generalised growing prosperity over the

decades leading up to WW1, wealth was very unevenly shared. According to the 1911 Census the

richest 1 per cent of the population held around 70 per cent of the UK’s wealth

in 1911. Real wages dropped 10% between 1900 and 1910, food prices went up and

new technology threatened skilled workers in engineering and other fields.

“In 1914 Britain was a country where 4% of the population

accounted for nearly 90% of the entire capital wealth, and where by contrast

30% of the population languished in abject poverty. There were serious tensions

within society.” (quote sourced from www.jakesimpkin.org)

It was poverty and the slow growth of wages that stood

behind the growing militancy of large sections of the working class. But poverty alone cannot

explain the growth of the willingness of workers to take action as many

workers had always suffered from poverty. For example, in York in 1899

the causes of primary poverty amongst those in work were low wages

(43.7%) and more than 3 children (12%).

The additional factor that began to play a major role was

the attempt by the capitalist class to make the working class pay for this

reduced competiveness by increasing the rate of exploitation of labour. This

led, therefore, to higher levels of surplus value being extracted from the

labour of the working class. New technology threatened skilled workers in

engineering and other fields along with so-called scientific management ideas

such as Taylorism, which attempted to break down every task into a single action,

thereby turning human beings into automatons.

“With productivity virtually stagnant, employers sought to survive in

an increasingly competitive world by turning the screws on labour, a

process which manifested itself in speed-ups, iron discipline, a more

militant stand over wages, reductions of fringe benefits, and moves to

limit trade union power. This process went hand-in-hand with the

amalgamation of industrial units and the general increase of unit size,

which tended to make management seem more distant and inhuman, and less

responsive to the complaints of individual workers.”

Trade unions

The period in the lead up to the Great Unrest also saw a

growth of trade unionism. In the 1870s the growth had been among skilled

workers. In the late 1880s mass trade union membership started among unskilled

workers so by 1890 some 8% of industrial workers were organised into trade

unions, making British workers the most organised of any major capitalist

country. By 1906 there were just over 2 million trade unionists and by 1914 the

number was over 4 million, or 27% of industrial workers.

This growth, combined with declining real wages, gave rise

to a new confidence that resulted in an explosion of strike action. Annual days

lost through strike action were up from an average of 3.6 million between 1902

and 1909 to 18 million between1910 and 1913. Another figure (quoted in

"British Capitalism, Workers and the Profit Squeeze" -Glyn and

Sutcliffe) puts the number of days lost through strike action as more than 10

million in 1908, 1910 and 1911 and more than 40 million in 1912. In the first

six months of 1914 almost 5 million days were lost through strikes, which

showed that the tempo of class action was only cut across by the advent of war.

Syndicalism.

As strikes developed throughout 1911 and 1912 there were

As strikes developed throughout 1911 and 1912 there were

features that were common to many of them. Previously unorganised sections of

workers, especially women, were drawn into the struggle and through struggle

there was the breaking down of barriers between workers that had previously

prevented united action, barriers arising from occupation, skill, gender and

religion. Finally there was the growth of syndicalist ideas and influence in

many of the strikes.

The Singer Strike in Clydeside typified the developing mood.

Working practices were being reorganised through speed ups as well as wage

cuts. Twelve female cabinet polishers went on strike and within two days most

of the 11,000 Singer workers joined them in solidarity. Leadership of a

practical and theoretical nature came from the syndicalist Industrial Workers

of Great Britain and also the Socialist Labour Party. Despite all of this there

was an unconditional return to work in April 1911 which was then followed by an

employer offensive which saw the sacking of 400 strike leaders. The realisation

however among workers of the need to organise was not lost and membership of

trade unions affiliated to the Scottish TUC leapt from 129,000 in 1909 to

230,000 in 1914. Similar actions involving women workers took place in Bristol

among sweet manufacturers and in London amongst garment workers.

In Durham in 1910 there had been an 8-week strike over the

attempt by coal owners to increase productivity through the implementation of a

three-shift working pattern instead of the two shifts that had been worked

since 1890. The strike was characterised by the direct action of men and women

against scabs. The strike laid the basis for the 1912 national strike of

mineworkers over the demand for a minimum wage. Two young syndicalist miners,

George Harvey and Will Lawther, challenged what they saw as the conservative

leadership of the Durham Miners Association.

Amongst miners in South Wales there was the growing

influence of syndicalism. The Next

Step platform of the Unofficial Reform Committee in the South Wales Miners Federation,

originally drafted by a weight checker said:

“Leadership implies power held by the leader, Without power

the leader is inept. The possession of power inevitably leads to corruption.

All leaders become corrupt, in spite of their own good intentions. No man was

ever good enough, brave enough or strong enough to have such power at his

disposal as real leadership implies."

These ideas reflected a growing belief, especially among

younger workers, that the leadership of the labour movement was holding back

the struggle of the working class, especially during strikes. Trade union

leaders were perceived as being prepared to spend more time in negotiations

with the employers and the government rather than engaging in militant action

to achieve success. On the political plain the Labour Party was also seen as

tail –ending the Liberals rather than having a distinct class policy in favour

of workers. Syndicalism therefore seemed to have some appeal.

What was Syndicalism?

It rejected political parties and fought against sectional

interests that divided the movement rather than uniting it. It fought for the

unity of all workers in one industry through one union. It saw the strength of

working class people as being at the point of production. After all does a wheel

not turn and a bulb not burn without the consent of the working class? For

syndicalists the capitalist system would fall after a general strike where

workers took control over their own workplaces.

What they unfortunately failed to recognise, however, was

that by merely taking control over factories the question of the state as the executive committee

managing the affairs of the capitalist class was completely ignored. It was this very state power that was

sending troops to shoot down workers taking industrial action. That is why

socialists fight not only industrially but also politically to conquer

political power, to take the state out of the hands of the capitalist class and

begin the process of building a new state that reflects the material interest

of those who create wealth, the working class.

As 1912 rolled on new strikes began to take place, many of

which were renewals of previous battles that had not been won. A delegate

conference of the Miners Federation of Great Britain decided to sanction a

national ballot for a general stoppage throughout the Federation to secure a

guaranteed minimum wage. On March 1st the vote was four to one in favour

although only a two-thirds majority was needed. The government, in panic,

rushed onto the statute books a National Minimum Wage Bill for the coal industry.

This again reflected the dual response of the ruling class and its political

representatives during this period – on the one hand give reforms to try and

diffuse the strike movement and on the other hand send troops to violently and

bloodily suppress the same movements. The miners rejected the government offer

and carried on with their action. Within a year membership of the Federation

had grown from just under 750,000 to over 900,000. Workers were organising.

In the lead up to this strike, The Times said it was:

"The greatest catastrophe that has threatened the country since the

Spanish Armada". A Tory MP called for siege rations and martial law to

defeat "socialist trade unionism". In Conservative circles some

wanted revolvers stockpiled to use against working class revolt.

Strike

In May of 1912 a threatened general strike on the docks

called by the Transport Workers Federation fizzled out. Support came from

80,000 London dockers who heeded the strike call but in other areas of the

country support was less solid. The men were forced to return to work without

any gains and, as had happened previously, the main trade union activists were

victimised.

So workers, organised and unorganised, engaged in battles

that were often bloody in order to defend wages and conditions. The massive

strike wave of 1912 continued into 1913 when 13 million days were lost. The

wave of militancy continued right up to the outbreak of WW1. During this

period, back in Llanelli even

school children went on strike protesting against the caning of a boy and

within days pupils in more than 60 towns were on the streets protesting their

grievances, with one boy telling a reporter from the Daily Mirror "our

fathers strike – why shouldn’t we?"

The relatively peaceful strike waves between 1887 and 1893

had been replaced by a greater willingness to fight by workers. The mass

strikes that led up to WW1 saw attacks on installations on the docks and

railways, the widespread destruction of machinery and bloody clashes with

scabs, employers, the military and the police with at a minimum 5 workers

killed and hundreds injured as well as strike leaders among the rank and file

being sacked.

The end result

of all of this was the massive rise in trade union membership to more than 8

million in the years following the end of WW1 when in 1919 the battle to defend

terms and conditions was recommenced and 35 million days were lost through

strikes.

Lessons for Today

History often rhymes but does not repeat itself. A hundred

years ago British capitalism was coming to terms with the decline in its

international competiveness by attacking the wages, terms and conditions of

workers, as well as raising the rate of exploitation of labour. Today, workers

are under attack as a decrepit capitalist system seeks to make workers pay for

a crisis that they did not cause. Then, as now, finance capital is seeking to

maintain its dominant role nationally and internationally.

Workers throughout 2011 have responded magnificently to

these attacks with demonstration and strikes on March 26th, June 30th and

November 30th. We have witnessed a growth in trade union membership as

previously unorganised workers have joined in the strikes and become trade

union members. This has been particularly true of younger workers.

Then as now we have also witnessed the blatant propaganda of

the press and the TV as it has sought to make us accept the myth that we are

all in this together so that we all need to make sacrifices to save the system.

The BBC has become in reality the mouthpiece of the political representatives

of capitalism, the Tory Party.

Many leaders of trade unions have reluctantly responded to

the demands of their members and have organised strikes and demonstrations to

protest against government plans to cut the public finance deficit at our

expense.

But as long as capitalism remains we will always be under

attack as those who own and control the system make us save it for them. We

must therefore put an end to capitalism and fight for a socialist solution to

the crisis. That begins by taking the banking and finance sector, as well as

the large monopolies, into public ownership under democratic control.

If we

are to avoid the defeats and bloodshed of a hundred years ago, we must fight

politically for an end to capitalism.