160 years ago, Charles Darwin’s epoch-making work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life first saw the light of day. His discovery of the mechanism by which species take form and evolve caused a sensation. Polite society and the church were scandalised.

By his discovery, Darwin had simultaneously dealt shattering blows to the Creation myth, and to the notion that the world is essentially timeless, static and unchanging. The latter was and remains a key prop of the ideology of the ruling class; the idea being that the status quo is the most natural form of society and therefore is essentially permanent.

Revolutionaries naturally welcomed the publication of Origin with open arms. “We spoke of nothing else for months but Darwin and the enormous significance of his scientific discoveries,” recalled Wilhelm Liebknecht, the German communist leader.

The form in which Darwin elaborated his ideas reflected the common prejudice that change is slow and gradualistic; nonetheless in essence he had uncovered the operation of dialectics in natural history in the same way that Marx discovered the dialectic of social evolution. As Marx commented in a letter to Engels, “Although it is developed in a crude English way, this is the book that contains the natural-historical foundation of our viewpoint.”

An unlikely revolutionary

Darwin was an unlikely revolutionary. Born in 1809 in Shrewsbury into a respectable, middle-class family, Darwin initially studied medicine in Edinburgh. While there he took an interest in natural history. He soon decided however that medicine wasn’t for him and he dropped out, enrolling instead in theology at Cambridge University.

Darwin was an unlikely revolutionary. Born in 1809 in Shrewsbury into a respectable, middle-class family, Darwin initially studied medicine in Edinburgh. While there he took an interest in natural history. He soon decided however that medicine wasn’t for him and he dropped out, enrolling instead in theology at Cambridge University.

Ironically, Darwin had hoped to live the quiet life of a parson in order to dedicate himself to peacefully contemplating nature. Fate intervened however when, shortly after graduating, one of his friends recommended him as a naturalist and gentleman companion for the captain of the HMS Beagle. The Beagle was due to set off on a five year surveying mission around South America and the islands of the South Pacific before returning to Britain via the Cape of Africa. The opportunity was unmissable for the 22-year-old, and on 27 December 1831, he set off.

Whilst on his travels Darwin collected an impressive array of specimens and kept a journal that propelled him to fame on his return. Gradually, in his multiple notebooks, a picture of a unique theory of the history of life began to emerge.

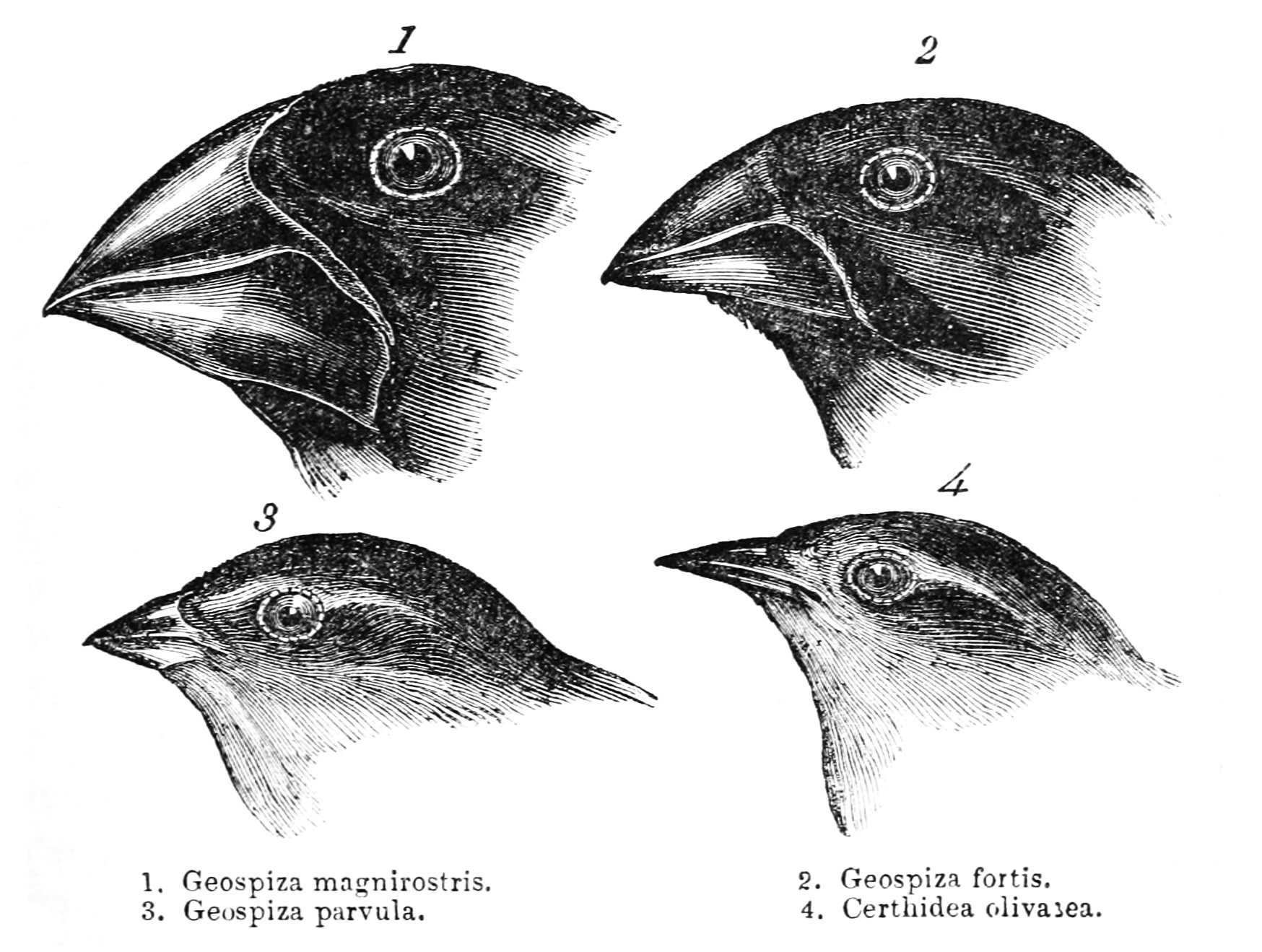

Among other observations, while examining finches on the Galápagos Islands, Darwin noted how the birds’ beaks were exceptionally well adapted to the ecological niches that they each occupied. Some ate insects, some ate berries – yet all had unique beaks that were excellently suited for the job. Nonetheless, their common ancestry with a genus unique to Latin America was clear.

It began to dawn on the young man that far from being immutable and static, species themselves were in a constant state of flux – coming into being and going out of existence.

Darwin’s new theory came to him gradually between stepping onto the HMS Beagle in 1831, and returning to England in 1836. Although a religious man, Darwin was scrupulously honest, and in the face of the evidence couldn’t help but draw materialist conclusions.

“I found it more and more difficult, with free scope given to my imagination, to invent evidence which would suffice to convince me,” reflected Darwin, “Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete.”

Evolution through natural selection

In Darwin’s youth, the idea of the transformation of species was not in itself a new one. The Ancient Greeks had their theories of evolution. And in the modern epoch Diderot, Lamarck, and even Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, had hypothesised that species evolved.

In Darwin’s youth, the idea of the transformation of species was not in itself a new one. The Ancient Greeks had their theories of evolution. And in the modern epoch Diderot, Lamarck, and even Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, had hypothesised that species evolved.

We don’t have to look very far for its evidence. It is all around us in the domesticated animals and plants that humans have moulded over millennia. Wheat, barley, rice and maize, for example, are all domesticated forms of wild grass. However, the qualitative differences between each is greater than that between what we recognise as distinct species in nature.

In Origin, Darwin showed that this process of domestication was the result of the interaction of two contradictory forces: on the one hand a tendency for offspring to inherit the features of their parents; and on the other hand a natural tendency towards variation among offspring.

By human selection of only those offspring which have the most desirable qualities (the hardiest, greatest yield, etc.), these small quantitative variations over many generations resulted in complete qualitative transformation of species as different as wild grass, wild boar and wolves – giving us wheat, pigs and pugs.

Darwin observed that humanity is not alone in selecting certain traits. Nature too carries out a kind of blind ‘selection’, as the better adapted populations thrive and the poorly adapted are wiped out. In essence, Darwin’s discovery was the connection between quantitative change (variation) and its transformation into qualitative change (speciation).

A 20 year wait

Darwin completely overthrew the idea that plants and animals were created as they are on the Sixth Day of Creation. He had good reason to expect the English bourgeoisie of his time to greet such materialism with disdain. They associated these ideas on the one hand with the radical thinkers of the French Revolution; and on the other with working-class socialism.

The pig-headed ignorance of the English bourgeoisie was something that shocked Engels on arrival in Britain, as he noted in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific:

“About the middle of this century, what struck every cultivated foreigner who set up his residence in England, was what he was then bound to consider the religious bigotry and stupidity of the English respectable middle-class. We, at that time, were all materialists, or, at least, very advanced free-thinkers, and to us it appeared inconceivable that almost all educated people in England should believe in all sorts of impossible miracles, and that even geologists like Buckland and Mantell should contort the facts of their science so as not to clash too much with the myths of the book of Genesis; while, in order to find people who dared to use their own intellectual faculties with regard to religious matters, you had to go amongst the uneducated, the ‘great unwashed’, as they were then called, the working people, especially the Owenite Socialists.”

The fear of the backlash from the pious hypocrites of the ‘respectable middle-class’ caused Darwin to pause for a full 20 years before publishing his findings. It was only when another naturalist, Alfred Wallace Russell, threatened to publish a very similar theory, that Darwin decided to publish Origin.

Exactly as he predicted, his writings provoked a furious response from newspaper editors, the Church of England and even a layer of the scientific establishment.

Darwin and Malthus

Despite the offence caused by his magnum opus, Darwin was himself a product of that respectable, English, middle class whose ostracism he feared. A curious source of Darwin’s inspiration was Malthus’ Principles of Population, which had been republished shortly before the voyage of the Beagle commenced, and which was all the rage among the middle classes in the 1830s.

After his five years away, Darwin returned to an England increasingly torn by class contradictions. The industrial revolution had created a burgeoning proletariat, which existed in the most wretched conditions in the cities. The bourgeoisie, terrified that it was sitting on a volcano of seething discontent, sought to ‘solve’ the problem of pauperism in 1834 with a new Poor Law, which forced the poor into hated workhouses, supposedly to ‘discourage’ their proliferation.

Malthus’ theories served to salve the consciences of the capitalists and landlords, and to justify the horrors that their system inflicted on millions. According to Malthus, population follows a geometric growth, while resources only increase arithmetically. Therefore it was only natural that there would be a struggle for survival in which the ‘fittest’ would live and the ‘unfit’ would perish. Pestilence, starvation and death were natural and to be expected – and not at all to be blamed on any social system!

Darwin believed himself to only be ‘extending’ Malthus’ theory of the geometrical law of population to the kingdom of the animals and plants. But, as Marx observed, by this extension Darwin unwittingly overthrew Malthus’ completely contrived idea that the planet’s resources tend towards arithmetic growth.

The tremendous revolutionisation of industry and agriculture that capitalism had ushered in at the start of the 19th century proved that the planet could carry an immensely larger population than existed in 1830 – or indeed today. It is not for the want of means of subsistence that men, women and children starve under capitalism, but because doing so is not profitable.

Does nature make leaps?

Fearing revolution, the bourgeoisie like all ruling classes before them, preach that the status quo is the only possible social order. In their philosophy of change, the capitalists conceive of a world that tends to perfect harmony and equilibrium. Or else, if they acknowledge change, they only acknowledge it as taking place in a slow, gradualistic, reforming manner. Above all, society and nature cannot make leaps.

If Darwin’s discovery was – in its content – dialectical, the form in which he developed this new theory reflected this profoundly anti-dialectical prejudice. Indeed, today we speak of ‘evolution’ and ‘revolution’ in common parlance as opposites, which absolutely exclude each other.

This philosophical prejudice has on more than one occasion left its impact on the natural sciences as well. While on the Beagle, Darwin studied with great interest Principles of Geology by the great geologist, Charles Lyell. Lyell was the world’s foremost advocate of slow, gradualistic change in the Earth’s history by processes operating over hundreds of millions of years, like erosion and deposition.

Although this view was a great step forward compared to the idea that supernatural intervention had moulded the Earth’s surface, it excluded revolutions and sudden qualitative leaps. The Earth had a kind of history – indeed a far vaster history than anyone had previously dared to imagine – but it was essentially a history of ‘unchanging change’. Gradual change took place, but the continents, seas and climate had always had essentially the same configuration and the same forces were said by Lyell to have operated with the same force over hundreds of millions of years.

These ideas had a profound influence on Darwin’s own interpretation of the history of life. For Darwin, the evolution of species was likewise a slow, gradual process of the smooth emergence of new branches on the tree of life, as branches emerge smoothly from the trunk of a tree. It had no room for discontinuities, catastrophes and rapid leaps.

The Cambrian explosion

The problem is that the fossil record does not bear this theory out – a fact that Darwin struggled with in Origin. For tens of millions of years, ammonites or trilobites were essentially unchanged. Then, suddenly, an adaptation appeared; or the species becomes extinct. Huge numbers of species were wiped out in a geological blink of an eye, and simultaneously new species radiated to fill the ecological vacancies that have been left open.

The problem is that the fossil record does not bear this theory out – a fact that Darwin struggled with in Origin. For tens of millions of years, ammonites or trilobites were essentially unchanged. Then, suddenly, an adaptation appeared; or the species becomes extinct. Huge numbers of species were wiped out in a geological blink of an eye, and simultaneously new species radiated to fill the ecological vacancies that have been left open.

The history of life is full of such sudden leaps. An equilibrium is established and may persist for aeons, before it is suddenly, rudely punctuated by catastrophic upheavals.

The marks of this process are found all over the fossil record in the so-called ‘missing links’ between ancestor and daughter species. Darwin explained away these ‘missing links’ by referring to the incompleteness of the fossil record. There was one event in Earth’s history, however, that completely confounded this view of evolution through slow, gradual development of species.

For the majority of life’s history on our planet, the only organisms that existed in abundance were single-celled organisms like cyanobacteria. The only fossils we have in abundance that are 600 million years old or older are simple, dome-like ‘stromatolites’. In life they were mats of single celled algae, piled up high. Then, some 550 million years ago, there was a tremendous explosion of multicellular animal life. Some of these creatures have been given names like Hallucigenia, on account of the fact that they look unlike anything we see today.

In his magnum opus, Darwin spent two chapters dealing with these troubling difficulties, which authorities in the scientific community had thrown back against the very idea of evolution.As Darwin noted:

“…the most eminent palæontologists, namely Cuvier, Agassiz, Barrande, Pictet, Falconer, E. Forbes, etc., and all our greatest geologists, as Lyell, Murchison, Sedgwick, etc. have unanimously, often vehemently, maintained the immutability of species.”

Darwin attempted to explain this ‘Cambrian explosion’ by reference to some as-yet-unknown geological process which had wiped out all evidence of pre-Cambrian fossils. He remained, however, unconvinced by his own explanation: “The case at present must remain inexplicable; and may be truly urged as a valid argument against the views here entertained.”

Punctuated equilibria

What happened 550 million years ago that lead to such an abrupt explosion? An interesting theory favoured by the evolutionary biologist Stephen J Gould was that one of the single-celled organisms sat on one of these great algal mats underwent a slight change. This change caused it to begin gobbling up its neighbours.

The change would have been so slight as to make the rogue cell barely distinct from its neighbours. It affected a complete revolution however. Suddenly the ‘prey’ cells that it was devouring found themselves forced to evolve means of evading the new predator on the block. Meanwhile, the predator cell in turn had to evolve means of overcoming new defensive adaptations. The result was an unprecedented acceleration of evolution. An evolutionary arms race began which hasn’t stopped to the present day.

Gould certainly never imagined we would find evidence of the story beginning in this way. It is all the more remarkable that this year, a team led by William Ratcliff at the Georgia Institute of Technology introduced a single-celled predator to a pool of single-celled algae. In the course of less than a year the scientists watched as it evolved before their eyes into a multicelled organism!

We may never have direct proof of whether it was a rogue grazing cell or some other apparently insignificant change that tipped the scale. Nevertheless, the Cambrian explosion marvellously illustrates an important principle in the evolution of matter. For hundreds of millions of years, barely perceptible variations in these primordial organisms and their ecosystem accumulated until a tipping point was reached. The leap towards complex, multicellular life was achieved.

In the 1970s, Stephen J Gould and his colleague Niles Eldredge developed this view into a generalised theory. Far from continuous evolution, most species exist in apparent stasis throughout their existence. However, beneath an unchanging appearance, small changes accumulate. These suddenly cause a ‘punctuation’ of the equilibrium and a sudden leap occurs, with new species evolving and old species being exterminated with tremendous rapidity.

Unsurprisingly, the theory was dismissed as ‘Marxist’ by some who abhorred the idea that revolutionary change is a law of nature itself. Indeed, Gould had been influenced by Marxist philosophy since his youth and it certainly informed his scientific work.

Key to this view was an understanding that evolution takes place extremely quickly in small populations. If a small group is geographically cut off from its parent population, speciation can occur rapidly. When the small population is once more geographically reconnected to its old habitat, its population can expand and quickly exterminate the species from which it split.

Notebook E

Many will naturally be surprised to know that Darwin himself actually hypothesised something very similar to what we now call ‘punctuated equilibrium’. As Niles Eldredge has noted, he laid out such an idea in a notebook written shortly after returning from the voyage of the Beagle, known as ‘Notebook E’. Unfortunately he dismissed it. Why did he do so?

In the notebook in question, Darwin pondered over whether geographical isolation was an important factor in the evolution of new populations. If it was, he surmised, it was likely that speciation would take place by rapid bursts. If not, it was likely that on a continent-wide scale new adaptations could only emerge by the slowest imaginable, gradualistic change.

Darwin, like all great scientists, was and remained a product of his time. In the epoch in which Darwin was writing, geographical change too was understood as taking place in a slow, gradualistic manner by geologists who repudiated Darwin’s theory. It is hardly to be wondered at that Darwin dismissed the idea that in such a gradually changing world, geographical isolation was likely to be the exception and not the rule.

Homo sapiens

The history of the evolution of our own species wonderfully illustrates the dialectical view of the process of evolution. At some point around five million years ago, the climate in East Africa began to change, becoming hotter and drier. As the climate changed, forests receded and a small population of apes were forced to abandon the relative safety of the forest and make their luck in the grasslands that surrounded it.

Rapidly, this small, geographically cut off population of apes was forced to develop an upright posture to look out for predators over the tall grass. This insignificant change began a veritable revolution.

Between homo sapiens and our nearest living relatives, the bonobo apes, there is as little as 1.2% genetic difference. The genetic difference between homo sapiens and ‘upright ape’ ancestors would be even narrower. By way of comparison, the genetic difference between any two human beings can be as much as 0.1%.

The leap from ape to man is only a few times greater than the leap from one human being to another. Indeed, we are physically very little removed from our nearest cousins. Anyone with deteriorating knees or a stiff back will have a constant physical reminder of how recently we descended from tree-dwelling monkeys, and how little we have adapted to our new upright posture.

And yet, in this witheringly small genetic difference is contained the greatest revolution that the organic world has undergone since the emergence of multicellular life. No individual species has had such a great impact on the world it inhabits.

The transition from ape to man

That the key turning point in the transition from ape to man was the upright stance, and with it the freeing up of the hand, is now widely accepted among evolutionary biologists. However, this was not always the case. Indeed, one of the first to propose this course of development was none other than Friedrich Engels.

That the key turning point in the transition from ape to man was the upright stance, and with it the freeing up of the hand, is now widely accepted among evolutionary biologists. However, this was not always the case. Indeed, one of the first to propose this course of development was none other than Friedrich Engels.

In his unfinished article The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man, written as part of his collection of notes on The Dialectics of Nature, Engels explained how the freeing up of the hand allowed our ancestors to engage in labour, transforming their world and thus transforming themselves.

As the human hand became capable of more complex operations, this reacted on the evolution of the brain, allowing for more complex, abstract thinking, and finally for speech also: the possibility of communicating abstract ideas to other members of the community.

Even late into the 20th century, however, eminent scientists continued to believe that it was an increased brain size that came first, and that only later did our ancestors develop tools and so on.

This reflects the idealist prejudice within class society, arising out of the division of mental and manual labour, which raises human thinking onto a pedestal, divorced from our interaction with the material world around us.

Capitalism’s impasse

Unlike Engels, or even Gould, what Darwin achieved he achieved without any training in philosophy and with no awareness of the dialectical method. As Trotsky explained:

“This highly gifted biologist demonstrated how an accumulation of small quantitative variations produces an entirely new biologic ‘quality’ and by that token he explained the origin of species. Without being aware of it, he thus applied the method of dialectic materialism to the sphere of organic life. Darwin although unenlightened in philosophy, brilliantly applied Hegel’s law of transition from quantity into quality.”

What Engels demonstrated is what can be achieved by the conscious application of dialectical materialism to science – something that we can never systematically achieve under capitalism.

Under this system, the natural sciences are in fact under attack. The ruling class is attacking education and research, passing on the costs of capitalism’s crisis to the youth and the working class.

In proportion to this, all sorts of outdated and backward ideas are bound to be revived, aided by the coffers of organised religion. In the United States, there is a mass movement of millions that proposes to teach Creationism as scientific fact. In Britain, 12% of people polled believed in an act of Creation; and only half were convinced that the theory of evolution is definitely true.

This demonstrates the impasse of the capitalist system, which today only breeds all kinds of ignorance. To take science and society forwards, therefore, we must overthrow this rotten system.

Only with socialism will we be able to finally unlock the full potential of humanity. In the words of Leon Trotsky:

“Man will become immeasurably stronger, wiser and subtler; his body will become more harmonised, his movements more rhythmic, his voice more musical. The forms of life will become dynamically dramatic. The average human type will rise to the heights of an Aristotle, a Goethe, or a Marx.”

And we might add, “or a Darwin”.