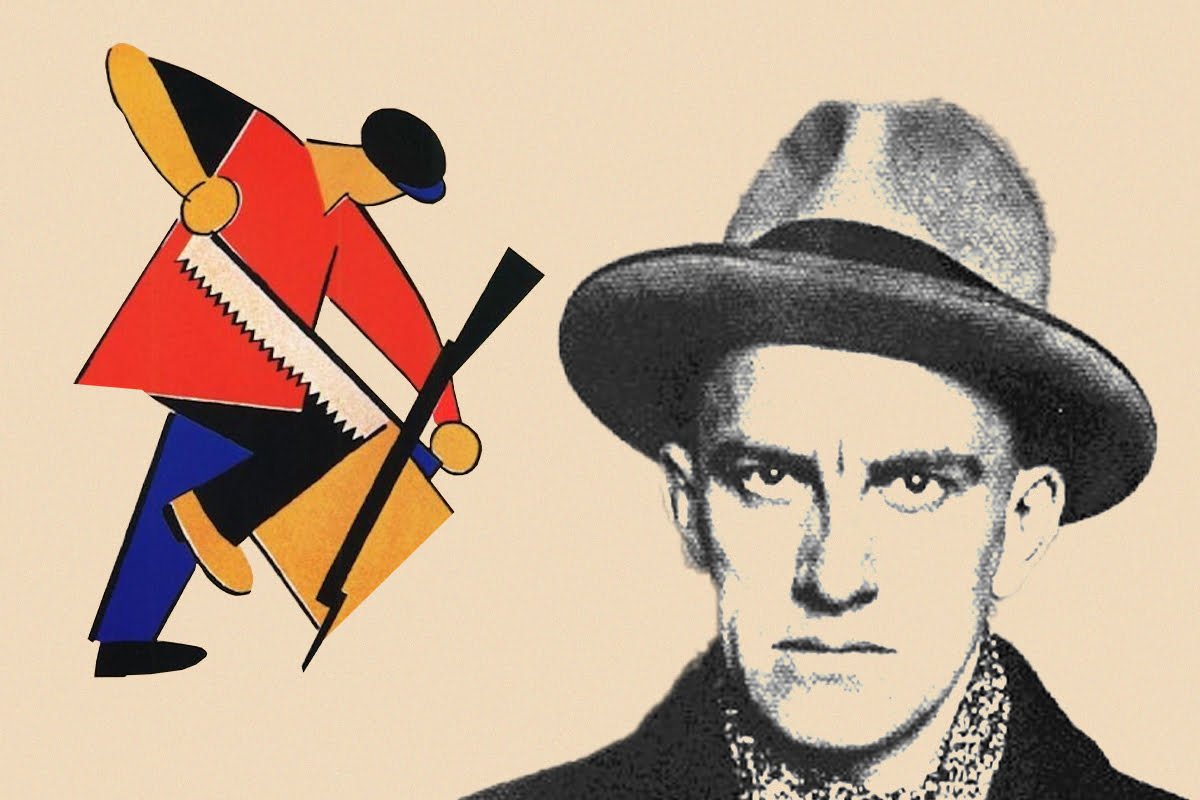

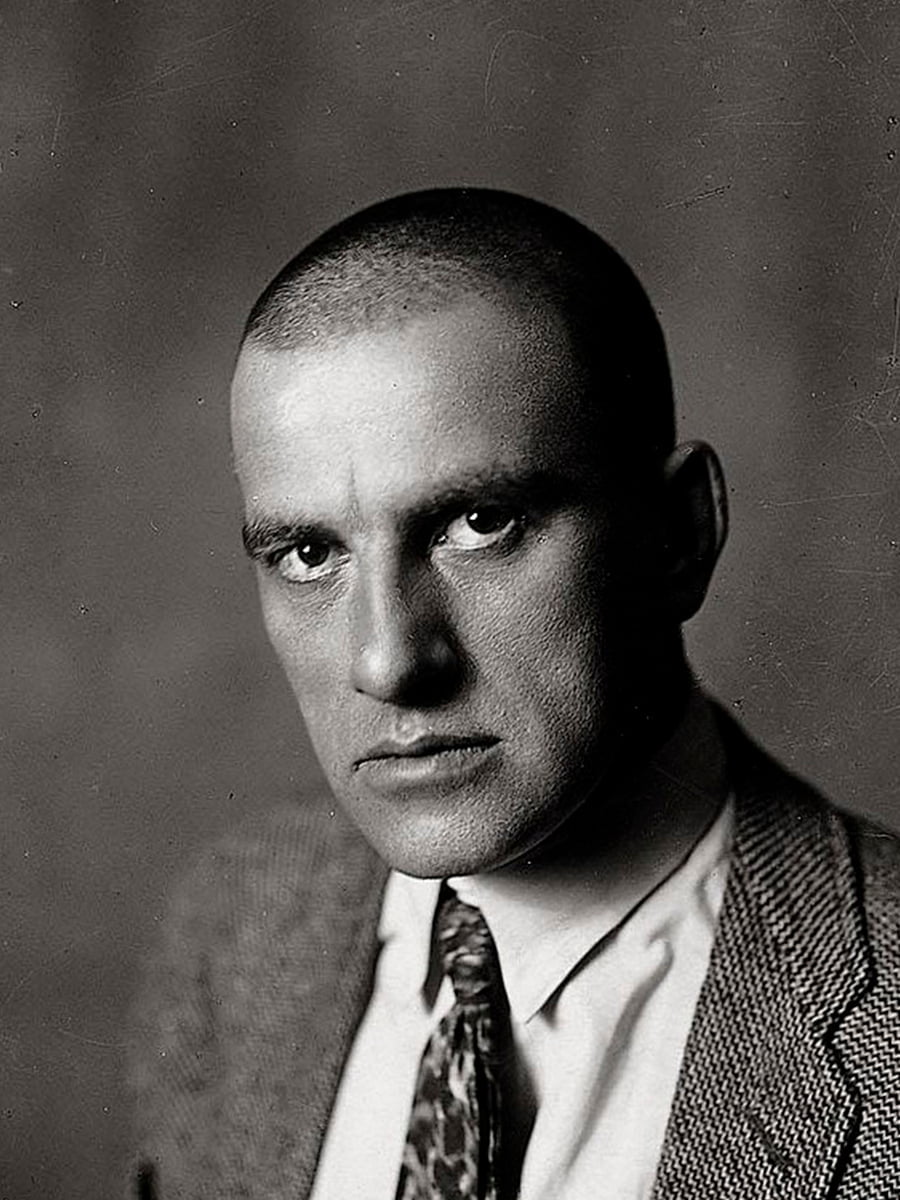

The great revolutionary artist Vladimir Mayakovsky was born 130 years ago, on 19 July 1893. His life, and the mark he left on poetry, theatre, and design, have captured the interest of radicals and revolutionaries ever since.

Today, as growing numbers of workers and youth become radicalised by the deepening crisis of capitalism, we remember Mayakovsky and celebrate his lifelong struggle for revolution, which he strove to give a voice to through his art.

Bolshevism

Mayakovsky was born in a small town in Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire, during a tumultuous period.

The revolutionary events of 1905 inspired a whole generation – including the young Mayakovsky, who devoured the songs and literature of the time.

His father was from a noble background, though by no means wealthy. When he died in 1906, the family were left with almost nothing, and were forced to move to Moscow.

There, while studying at the 5th Classic Gymnasium, Mayakovsky aligned himself with the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), becoming an active revolutionary.

He took part in Marxist reading groups, propaganda, and other practical activity during the period of black reaction that followed the defeat of the 1905 revolution.

Oppressive Tsarist laws and secret police forced the party and its members underground. Mayakovsky was arrested several times for working at an illegal printing press, smuggling literature, and breaking political prisoners out of jail.

While in prison, Mayakovsky studied art and literature, and began writing poetry.

He was always dissatisfied with the greats, like Alexander Pushkin and Fyodor Dostoevsky. He felt deeply that the hypocritical ideals and sentimental lyricism of bourgeois literature were utterly unfit for the new turbulent period, and called for them to be cast “overboard from the ship of modernity”.

This desire to break with the past reflected a genuine revolutionary spirit. But it also spoke to some of the limitations of Mayakovsky’s thought.

In his haste to chart a new course for Russia’s cultural life, he had a tendency to throw the baby out with the bathwater. In fact, on cultural matters, the working class had much to learn from Russia’s grand artistic lineage.

Futurism

On release from prison, Mayakovsky drifted from the Bolsheviks. Enrolling at the Moscow Art School in 1911, he fell in with a group of rebellious bohemians who together would forge the Russian Futurist movement.

They shared with Italian Futurism a hatred of the past and a fascination with speed, technology, and the big city.

This appeared as a total anathema to the stultifying obelisk Tsarist Russia had become, and the wooden ‘realist’ tradition that dominated its cultural output at the turn of the 20th century.

The Russian movement, however, developed somewhat independently from its Italian counterpart. The left Futurists around Mayakovsky, in particular, were hostile to the fascist sympathies held amongst their Italian counterparts, by the likes of Marinetti.

The Russian Futurists attacked bourgeois art and morality, expressing a mood not unlike that which prevails amongst many young people today, who are rightfully repulsed by the degeneration and profiteering in art and wider society.

Futurism was always constrained by its origins. It reflected the youthful contempt of petty-bourgeois intellectuals – disgusted with the old order and its stagnant cultural life, but ill-equipped to fight for a new one.

Nevertheless, as Trotsky later wrote: “If the Futurist protest against a shallow realism had its historic justification, it was only because it made room for a new artistic recreating of life, for destruction and reconstruction on new pivots.”

Russian Revolution

As the First World War broke in 1914, and class struggle in Russia began to grow again, Mayakovsky’s art became increasingly political.

When, in 1917, the Russian masses overthrew the hated Tsar, and fought to establish the first workers’ state in history, Mayakovsky put his considerable talents entirely at the service of the revolution.

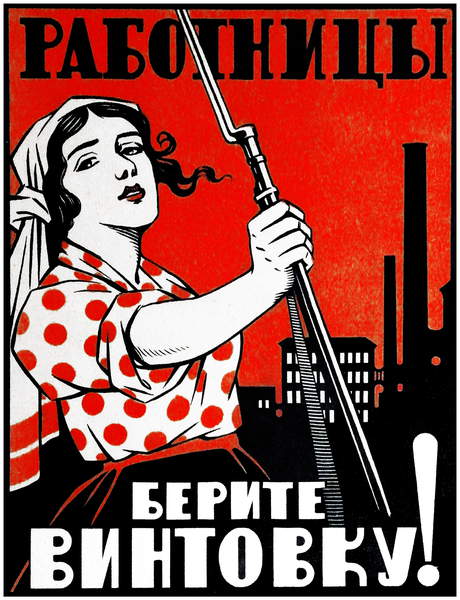

He wrote great rallying poems such as ‘Left March’. He produced a play celebrating the October Revolution. And he painted Bolshevik posters.

The revolution provoked an enormous flourishing of art. The gilded doors of Russia’s immense cultural legacy were opened to the masses for the first time, and a generation of artists were inspired to capture the spirit of the new world through their craft.

Mayakovsky became a highly celebrated and popular artist, with his poetry enjoying particular acclaim.

He threw himself wholly into, as he saw it, the revolutionary task of reshaping Russia’s cultural life. This involved collaborations with many of the greatest artistic figures of the time: the constructivist painter Malevich; theatre director Meyerhold; graphic designer Rodchenko; legendary filmmaker Eisenstein; and even the young composer Shostakovich.

Yet, despite holding the latter’s personal admiration, Lenin did not hold Mayakovsky in great esteem. He was highly critical of the political limitations of the whole Futurist school, suspicious of the fascist sympathies of its Italian adherents, and justifiably exasperated at the idea of navel-gazing bohemians trying to construct a ‘new culture’ while the workers and peasants of Russia had nothing to eat.

He dubbed some of Mayakovsky’s art, in particular, “hooligan communism”. He regarded Mayakovsky’s sometimes obscure work as merely pretentious. His opinion on this later softened. And part of his earlier dismissal was perhaps informed by his self-confessed conservatism on artistic matters.

Trotsky – while sharing many of Lenin’s political criticisms – was more personally invested in experimental art, and recognised Mayakovsky’s enormous talent, naming him the “greatest poet of the [Futurist] school”. But he also saw the artist’s weaknesses.

He criticised Mayakovsky’s unwillingness to engage with the stark realities of post-revolutionary Russia: the backwardness that would need to be overcome for there to be any question of raising Soviet society’s cultural level to the heights envisioned by this petty-bourgeois idealist.

For Trotsky: “Mayakovsky’s revolutionary individualism poured itself enthusiastically into the proletarian revolution, but did not blend with it. His subconscious feeling for the city, for nature, for the whole world, is not that of a worker, but of a bohemian.”

Counter-revolution

Later, as the Stalinist bureaucracy grew powerful in the isolated workers state, Mayakovsky attacked the red tape and stupidity of the bureaucrats in poems like In Re: Conferences.

While still not a fan of the poetry, Lenin praised the political content of this work as “absolutely right”.

As Lenin’s health worsened, Mayakovsky rightly railed against those who sought to transform the Bolshevik leader from flesh-and-blood revolutionary into a harmless icon.

In a 1923 editorial for the Left Art Front (LEF) journal he helped found, Mayakovsky wrote:

“We insist

Don’t stereotype Lenin

Don’t print his portrait on placards, stickybacks, plates, mugs and cigarette cases.

Don’t bronze-over Lenin

Don’t take from him the living gait and countenance.”

After Lenin’s death, Mayakovsky’s increasingly critical line made him a target. His critique of the Stalinist clique in the satirical play The Bathhouse provoked a vicious campaign against him.

Vladimir Yermilov, a literary critic and Stalinist attack dog, implied that The Bathhouse expressed sympathy for the ideas of Leon Trotsky’s Left Opposition.

This cultural epigone might have actually had a point. Mayakovsky was always an avowed internationalist, who saw the Russian Revolution as the starting gun for world communist revolution.

The association with Trotsky was intended as a Mark of Cain. It was followed by a smear campaign in the Soviet press, with Mayakovsky being drowned out at public readings by jeering audiences whipped into a frenzy by Stalinist calumny.

Just as Stalin murdered all the old Bolsheviks, in order to consolidate the privileges of the bureaucracy, so too in art he waged a brutal counter-revolution. This later included enforcing a new “shallow (socialist) realism” as the only accepted style in the Soviet Union.

Mayakovsky ultimately could not withstand the withering effect of Stalinist counter-revolution. In April 1930, at the age of 36, he took his own life in mysterious circumstances.

Legacy

Mayakovsky’s revolutionary legacy was still feared by the bureaucracy. Their anxiety only intensified when his funeral became the third-largest event of public mourning in Soviet history, with 150,000 in attendance.

In a cynical about-face, in 1935, Stalin proclaimed Mayakovsky to be “the best and most talented poet of our Soviet epoch!”

The bureaucracy proceeded to strip Mayakovsky of his humanity, converting him – just like Lenin – into another harmless icon; a mere propagandist. His oppositional works were censored or altered, while statues and public squares unveiled in his honour.

This acted as nothing short of his “second death”, as fellow Futurist Boris Pasternak later wrote.

Today, the last remnants of the revolutionary Mayakovsky continue to be wiped out in defence of the status quo.

His political works are buried under academic gossip about his lovelife and personal struggles. Statues and streets dedicated to him are torn down and renamed. In Ukraine, for example, a Mayakovsky Street was recently renamed in honour of Boris Johnson.

Get organised

Those of us who are not content with the status quo of the world today, and who call ourselves communists, remember the real, complex, inspiring legacy of Mayakovsky: his courageous revolutionary struggle, and great artistic achievements.

In doing so, we heed the words of Trotsky. Art has a role to play in revolution, but cannot be achieved through art alone.

It is only through conscious organisation, education, and persistent struggle that this decrepit system can be overthrown, once and for all.

One can say of Mayakovsky that, from a young age, he recognised the need to get organised and fight for revolution. Communists today must follow this example.