‘Many strange stories have been told about Karl Marx…but

to those who knew [him] no legend is funnier than that common one which

pictures him a morose, unbending, unapproachable man, a sort of Jupiter, even

hurling thunder, never known to smile, sitting aloof and alone in Olympus. This

picture of the cheeriest, gayest soul that ever breathed, of a man brimming

over with good humour, whose hearty laugh was infectious and irresistible, of

the kindliest and most sympathetic of companions, is a standing wonder – and

amusement – to those who knew him’.

So wrote Eleanor, Marx’s youngest daughter, in A Few

Stray Notes recalling happier days in the family household. Opponents would

no doubt see things differently as Marx usually took no prisoners, and even

with acquaintances patience for Marx was not always a virtue.

Eleanor recalls how she wanted

to ‘run away to join a man-of-war’ and how Marx, or Mohr as his intimates

called him, assured her that while it was possible she ought to keep it a

secret until she could develop her plans. Mohr would read to his children:

Homer, the Niebelungen Lied, Don Quijote, and the Arabian

Nights, were favourites while Shakespeare – Marx peppered his work with apt

quotations from his plays – was part of the family’s staple

diet.

Born in 1818 into a well-to-do

Jewish family in Trier, Germany, Marx attended the

University of Bonn ostensibly to read law yet, to the hair-pulling of his

father, spent much of his time socialising and debt-ridden before transferring

to Berlin. There he met various young radicals such as Moses

Hess, and the atheist

lecturer, Bruno Bauer,

who introduced

Marx to the writings of Hegel, the university’s professor of philosophy until

his death in 1831.

During this period he fell

for an aristocrat, Jenny von Westphalen, ‘the most beautiful girl in Trier’.

They were married in 1843: Jenny’s white-knuckle ride with Karl, involving

exile, bailiffs and pawnbrokers, and a unique contribution to mankind, had

begun. She would later write: ‘the memory of the days I spent in his little

study copying his scrawled articles is among the happiest of my life’.

Marx hoped for a lectureship,

but finding university careers closed to radicals he moved into journalism and was appointed editor of

the liberal Rheinische Zeitung in October 1842, during which he

criticised Prussian absolutism and defended the freedom of the press.

After

the Prussian authorities banned the paper in January 1843, Marx moved to more

liberal pastures, Paris, to join a journal-in-exile, the Deutsche-Französische

Jahrbücher but

only one edition was published before Marx and Ruge, the founder,

fell out (many of Marx’s acquaintances were brief), but he did befriend the

Romantic poet Heine (whose weaknesses, as he saw them, he overlooked), and met

Engels. Engels showed Marx what would be his The Condition of the Working Class in England (he

later donated the book’s royalties to Marx), and established an historic and

lifelong friendship.

Marx’s

economic writings can be considered in the following chronological sequence: Economic

and Philosophical Manuscripts, Grundrisse, and Capital, and

it was in Paris that Marx completed the former. However, he was deported at the

instigation of the Prussian envoy in 1845 for libel, and later exiled from

Belgium by King Leopold I in March 1848 for conspiracy, though not before

writing The German Ideology and finishing The Communist Manifesto.

He

returned to Germany during the revolutionary turmoil that was 1848 and in June,

leaving himself penniless, launched the daily Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a

democratic voice, with money from an inheritance. This newspaper, though

embroiled naturally in local events was internationalist from the start, paying

close attention to developments in neighbouring France and the Chartists in

Britain.

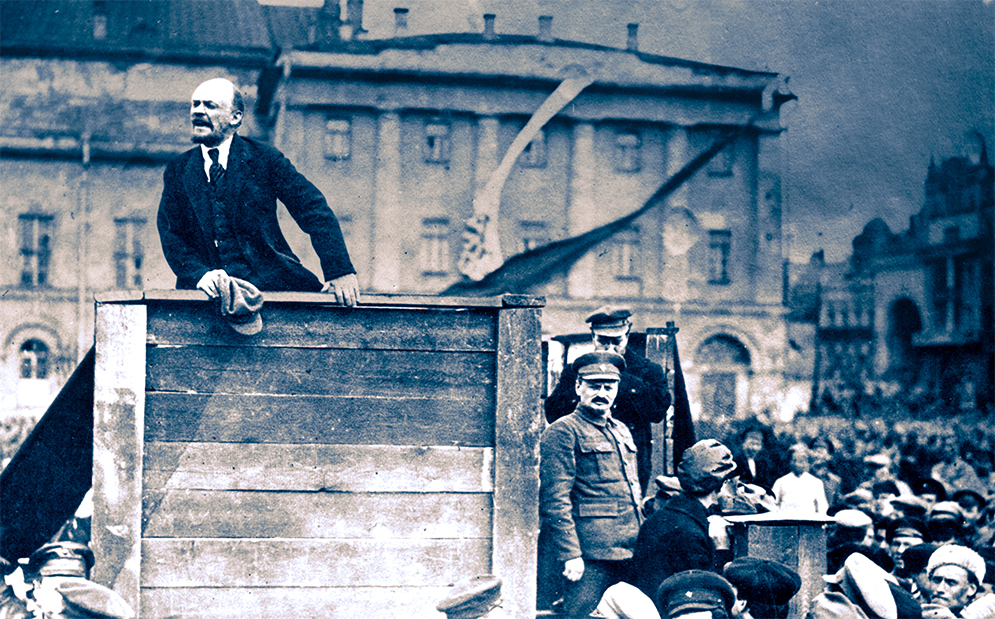

Police

arrested workers’ leaders, while Marx addressed a mass meeting of workers in

Cologne’s old market place. Martial law was declared and the newspaper was

forced to suspend publication. The final issue was printed in a defiant red

ink, the editors calling for the ‘emancipation of the working class!’ More

lawsuits, alleging ‘incitement to revolt’, were issued against Marx.

Unimpressed, Marx stood for president of the Cologne Workers’ Association in

October 1848 and won.

We know

of the 30 fruitful years Marx spent researching Capital in the British

Library, but it was in agitation that Marx was at his best. He appeared before

magistrates in July 1848 charged with ‘insulting or libelling the chief public

prosecutor’ whom he had publicly accused of brutality, and stood trial the

following February. Never one to mince words, he addressed the crowded

courtroom:

‘I prefer to follow the great events of the world, to

analyse the course of history, than to occupy myself with local bosses, with

the police and prosecuting magistrates. However great these gentlemen may

imagine themselves in their own fancy, they are nothing, absolutely nothing,

in the gigantic battles of the present time…it is the duty of the press to come

forward on behalf of the oppressed in its immediate neighbourhood…The first

duty of the press now is to undermine all the foundations of the existing

political state of affairs’.

He was

acquitted amid loud applause. However, after another court appearance (the

following day), the Prussian authorities (in May) recommended Marx be deported

and he left for Paris a month later. By August he was forced to leave France

again – and sailed to Dover.

Many

figures inspired Marx, such as Prometheus (in Aeschylus’ play) who sought to displace the

tyrannical gods by vesting their powers among men. In political economy, the

work of Smith, Ricardo, and Mill was instrumental in Marx’s forging of Capital.

Their shortcomings proceeded from a mistaken recognition that capitalism was

natural and here forever.

In Marxist

philosophy, it was the work of two outstanding individuals, Hegel (1770-1831),

the ‘mighty thinker’ as Marx later called him, and Feuerbach (1804-1872), that

Gulliver of materialism, which laid the philosophical foundation stones of what

today we call Marxism: Marx mined their riches and revolutionised

them.

In The Science of Logic,

Hegel, argues that everything around us is dialectical; instead of considering

our surroundings as finite, complete, stable, and ultimate they are in fact

changeable and transient. A ‘whole’ consisted of its parts, and counterpart(s);

and they comprise the ‘whole’, when taken together (he gives the human body as

an example). Central to dialectics, too, is motion: ‘Wherever there is

movement, wherever there is life, wherever anything is carried into effect in

the actual world, there Dialectic is at work’.

In

Hegel’s philosophy, however, nature was derived from thinking, ideas, and God

so what was their origin? ‘Then came Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity’, Engels

stated later. ‘With one blow it pulverised the contradiction…it placed

materialism on the throne again. Nature exists independently of all philosophy.

It is the foundation upon which we human beings, ourselves products of nature,

have grown up. Nothing exists outside nature and man, and the higher beings our

religious fantasies have created are only the fantastic reflection of our own

essence…One must oneself have experienced the liberating effect of this book to

get an idea of it. Enthusiasm was general; we all became at once Feuerbachians’

(Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy).

Credit

for turning Hegel’s idealism on its head belongs to Feuerbach, his own pupil,

and he earned Marx’s gratitude: ‘I am glad to have an opportunity of assuring

you of the great respect and – if I may use the word – love which I feel for

you’ Marx wrote to him in 1844. ‘You have provided a philosophical basis for

socialism’.

For Feuerbach, however, nature simply ‘existed’ and

warranted ‘admiration’. In Capital Marx insists that nature must be

respected ‘for man is part of nature’, yet also stresses, in The

German Ideology, that even natural objects were the products of historical

circumstance and human practice. For example, ‘the cherry-tree, like almost all

fruit-trees, was, as is well-known, only a few centuries ago transplanted by commerce

into our zone, and therefore only by this action of a definite society in a

definite age has it become a ‘sensuous certainty’.

Marx gave a revolutionary voice,

using the method of dialectics, which he separated from Hegel’s theological content, to those

historical and material circumstances, and in this his role is unique. In real

terms his contribution to our understanding of society, as one based on

material, or economic, class interests has made a universal impact particularly

in the field of history. Moreover, the one thread which runs through Marx is

that ordinary human beings must struggle for what is rightly theirs, and this

philosophy is the starting point for the downtrodden in today’s society.

At Marx’s graveside in Highgate,

London (on 17th March 1883), Engels paid a glowing tribute to his

brother-in-arms when he told the gathered mourners that ‘fighting was his

element’. Why is this important?

In The

Eighteenth Brumaire of Louise Bonaparte Marx wrote that while ‘men make their own history…they do not

make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances

directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past’ (Marx 1934:10). Life

is not what you make it. Yet, historical materialism also dismisses the

notion that man and society is held in check, throughout the ages, by

omnipresent conditions. Such would be a mechanistic interpretation of history,

and one which cannot explain how circumstances change from one period to

another. Those circumstances which

shape and form our consciousness are not independent of human activity. Rather,

man is both a product and changer of circumstances.

‘Circumstances make men just as much as

men make circumstances’ (The German Ideology).

There is, then, a dialectical relationship between those definite conditions into which we are

born and which play a role in shaping us on the one hand, and practical activity which changes those conditions on the

other and, notwithstanding his recognition of Marx’s personal vitality, this is the real significance of Engel’s

tribute.

We all enjoy quoting Marx, but

his own favourite was Terence’s ‘Nothing

human is alien to me’ and it is a maxim by which he lived. Marx

loved a good sing-song, German folk-tales – in one letter Engels asks him to

return his copy of Grimm – Greek art and mythology (he read Aeschylus in the original), and

thought the world of Shakespeare (nobody, he said, portrayed money better – see

Timon of Athens).

The Marx family, as countless

others in Victorian London, was plagued by ill-health and persistent poverty.

When Franziska, Marx’s third daughter, died of bronchitis in 1852 aged

one-year, a neighbour lent the family £2 to pay for a coffin.

Destitution was partly relieved

by work for the New York Herald Tribune

and by Engels’ renowned support. In April 1855, the fine-spirited

Edgar, Marx’s 8-year-old son’ died of tuberculosis. Marx

clearly struggled against the tide during his lifetime, but the death of his

little jester was different. In a tear-rendering letter to the German

socialist, Lassalle, three months after Edgar’s death, Marx was still

inconsolable: ‘The death of my child has shattered me to the very core…My poor

wife is almost completely broken down’.

Marx continued to fight, of

course – Capital progressed and he was elected to the General Council of the First International

in 1864 – but history will forgive him if a light was dimmed in this

affable, cultured man.

Eleanor concludes her Few

Stray Notes, quoting Macbeth: her parents ‘sleep well’, after

‘life’s fitful fever’: ‘If she was an ideal woman’, she says of her mother, ‘he

– well, he was a man, take him for all in all, we shall not look back upon his

like again’.

Indeed, we shall not.