110 years ago, in 1907, a strike in Belfast over wages by dockworkers, coal labourers and others united both catholics and protestants against the ruthless bosses. Although ultimately defeated, the strike remains an important historical demonstration of the power of the working class when united.

In 1907, a strike in Belfast over wages by dockworkers, coal labourers and others – a struggle led by that great socialist Jim Larkin – united both catholics and protestants against the ruthless bosses and almost led to a civil war with troops being brought in to break the strike. Even sections of the police would come out in support of the strike. Although, ultimately defeated, the historian Emmet Larkin, writing in 1965, said of the strike: “There had not been such an upheaval in a hundred years, and there has not been one since.”

One hundred and ten years later, in an article by Gerry Ruddy originally published in 2012, we look back at this momentous period of class struggle and what can be learnt from it.

Belfast in 1907 was a hotbed of militancy. It was the fastest growing city in the British Isles. Its most successful industries were labour intensive. Although once described by a former Lord Mayor as “an elysium of the working classes,” Belfast had a sharp divide, not only between catholics and protestants but between skilled and unskilled labour. The skilled workers shared in the general prosperity of the time and had wages unsurpassed outside of London. However the unskilled who flocked into Belfast from the countryside did not share in this prosperity.

It was estimated that to support a family at the time the minimum weekly income needed to be 22 shillings and five pence, yet an unskilled labourer only earned 10 shillings a week. The wages of women and children made up the difference.

James Larkin

In May 1906, 17,000 spinners, weavers and others struck for wage increases and in 1907 there were 34 strikes that included textile operatives, engineering, service trades, navvies and other labourers. Moreover the first annual conference of the British Labour Party was held in Belfast in early 1907. Labour organiser and socialist agitator James Larkin attended that conference. He had come to Belfast intent on the organisation of Belfast’s 3,100 dockers, 2,000 of which were casual ‘spellsmen’ hired at low rates on a daily basis.

Larkin, born of Newry parents but brought up in Liverpool, arrived in Belfast on 20th January 1907 and soon set up branches of the National Union Of Dock Labour in Belfast and Derry. A previous attempt to organise the men had failed due to an extended lockout and a sustained press campaign labeling the union leaders as “Fenians.” This time, by April over 2,000 were organised, by May it was 4,500 in the union.

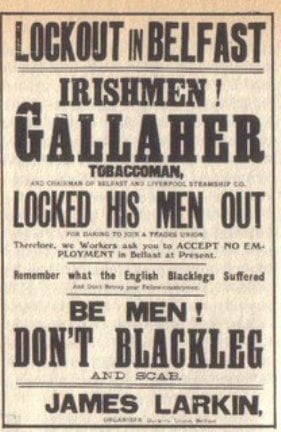

On the 6th May 1907, dockers at the York dock in Belfast objected to working with two non-union men and walked out. The union advised them to go back to work for now. When they did, they found that they had been replaced by fifty strikebreakers imported from Liverpool. The following day, the union members drove out the scabs from the Kelly Coal Quays and the sheds of the Belfast Steamship Company. While the Kelly bosses capitulated, granting union recognition and a pay rise, another major dock-owner and coal merchant, Thomas Gallagher, refused to negotiate.

Gallagher was also a shareholder in Belfast Ropeworks company and he realised the implications of allowing unskilled labour to organise in the city. Soon he had hundreds of scabs working on the quays, surrounded by the police and troops requisItioned by the Lord Mayor of Belfast.

Sympathy strikes

Larkin responded in kind. When Gallagher dismissed seven girls in his tobacco factory for attending a lunchtime meeting called by Larkin, one thousand of their fellow workers walked out on May 16th.

Larkin responded in kind. When Gallagher dismissed seven girls in his tobacco factory for attending a lunchtime meeting called by Larkin, one thousand of their fellow workers walked out on May 16th.

Stone throwing and attacks on scabs occurred. Larkin himself was arrested for attacking a scab. While the tobacco strike was crushed, the dockers strike escalated. In June, 350 iron moulders began a seven week stoppage which affected 2,000 engineers indirectly.

On June 26th, Larkin called out all Belfast dockers demanding better pay and union recognition. The following day 1,000 carters struck in sympathy and for their own wage claims. So Larkin called on other workers not to handle goods from companies in dispute. All carters came out on a sympathy strike, the ports were at a standstill. Engineers and boilermakers around Belfast also came out on strike.

This produced a response from 18 coal merchants who said that, from 15th of July, they would not employ any union labour. This, in turn, saw 880 porters and carters joining the struggle. In the meantime, it took until 19th July for the union leadership to sanction strike pay. Up to then it was the Belfast Trades Council and local unions who sustained the strikers and their families.

State intervention

Thousand flocked to Larkin’s public open air meetings and rallies. Despite all this occurring around the 12th of July, sectarianism did not break the strike.

Larkin, having grown up in Liverpool, was aware of the nature of sectarianism and indeed at one stage offered to hand over the leadership of the strike to Councillor Alec Boyd, an orangeman and trade unionist. Significantly, riots in support of the strikers broke out on the mainly protestant Ravenhill Road and the mainly catholic Falls Road. A case of East and West Belfast united in a common cause of class unity.

On the 16th of July, Larkin made a speech in which he outlined discontent within the police ranks over their pay, conditions and how they had been made to protect scabs. Larkin reminded the members of the police force that they were underpaid. The police demands in 1907 were identical to the trade unions on strike. On the 24th, the police mutinied and over 2,500 troops were drafted into Belfast with over 200 police in turn being transferred to country areas. By August 6th, the police mutiny was over.

The state intervention was increased. British troops sealed off the quays. Cavalry escorted the goods traffic. Warships anchored in Belfast Lough.

Establishment fuels sectarianism

Then, as now, the media threw its considerable forces behind the employers and the state forces. During the period of the strike the press described Larkin as a “socialist” an “anarchist” or a “syndicalist” and a “papist”. On August 11th, armed forces flooded the Lower Falls area provoking riots. Soldiers shot dead two people and wounded scores of others. The mainstream labour movement was quick to distance itself from the militancy of the workers. Leading Labour MP Philip Snowden condemned “that portion of the Belfast population which is almost as much accustomed to rioting as a savage tribe is to constant warfare.”

This almost unconscious racism of course fed into the sectarian mindsets in Belfast. Thus the heightened sectarian and political tensions made it extremely difficult for the strikers as August progressed. Larkin sought arbitration but only the carters’ employers agreed. The union leadership in England came to Belfast and effectively caved in to the bosses, leaving the dockers isolated and unable to continue. As a result the striking dockers were defeated and permanently replaced by scab labour by the end of August.

It was a terrible defeat for the workers but in that strike there were important signals of what was possible. The use of the sympathetic strike brought a solidarity that transcended the sectarian divisions even if it was just for a short time. The explosive nature of the personality of Larkin showed what charismatic figures, if unflinching in the face of adversity, can do. Larkin was not afraid to take on not only the employers but also the forces of the state, in defence of the weakest sections of the working class. It also underlined the essentially conservative nature of the leaderships of the British trade unionism ready to secure a deal at a moment’s notice and without consulting the workers.

For workers’ unity

At the beginning of the 20th century the unskilled workers were unorganised and without representation. The Belfast strike gave hope to these workers that they too could become unionised.

However the strike also exposed the ways that the ruling class will resist any attempts to curtail their power. They acted ruthlessly when their own police force mutinied, they unleashed their troops on one section of workers to heighten sectarian tensions and they used their media, their churches, and their liberal establishment to demonise and slander the workers and their leaders.

Now an unprecedented attack has been launched worldwide on the gains of the 20th century. Attempts to divide workers on public versus private sector, or catholic versus protestant or Shia versus Sunni lines must be resisted. Let us learn from the past and make permanent the class unity that existed if only for a magnificently short time in Belfast 1907.