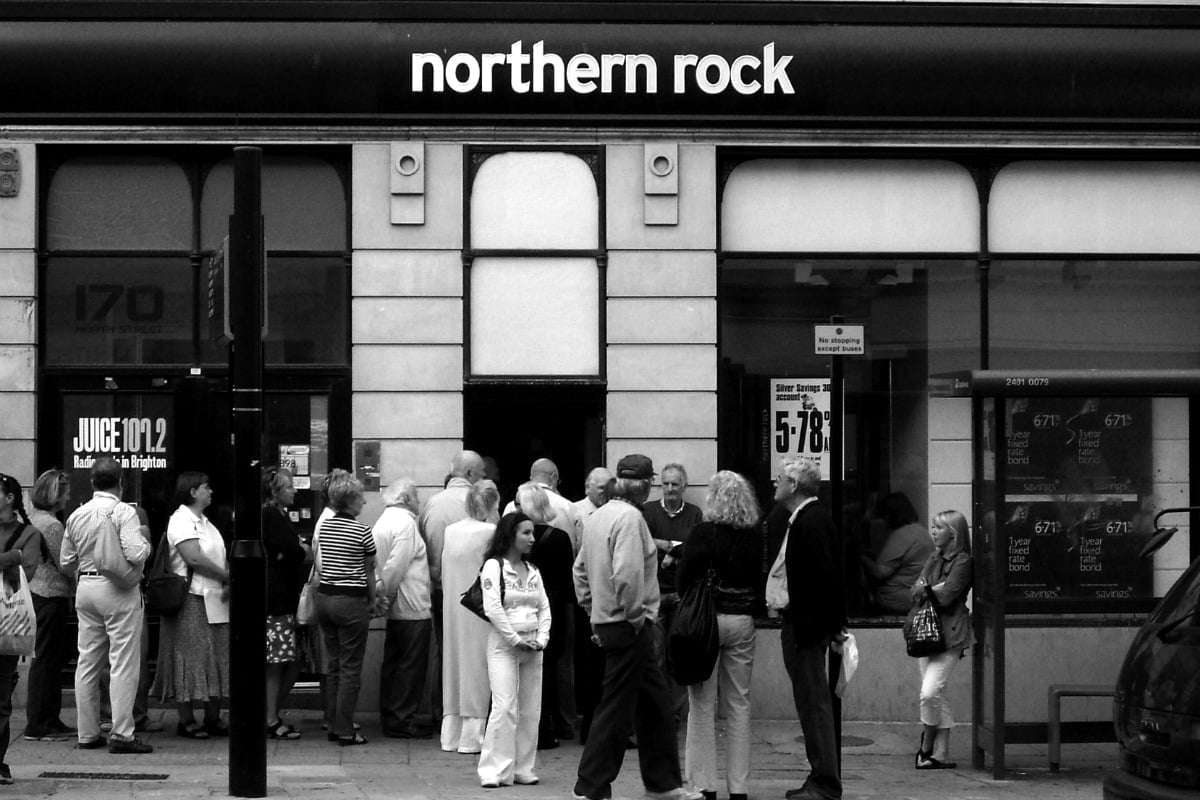

Ten years ago today, on 14th September 2007, Northern Rock customers were forming long angry queues outside the beleaguered bank’s branches. It would turn out to be an historic turning point. Within a year, the whole world financial system was teetering on the verge of collapse, and together with it, the capitalist system. Rob Sewell analyses the beginning of the Great Recession, one decade on.

Ten years ago today, on 14th September 2007, Northern Rock customers were forming long angry queues outside the beleaguered bank’s branches. It would turn out to be an historic turning point – the first run on a British bank for 144 years.

Over a single weekend, some £4.6bn was withdrawn by savers, equivalent to 20% of the bank’s deposits. This “run” soon pushed the bank towards bankruptcy and Northern Rock was quickly nationalised within months, along with the Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds. This rescue was deemed necessary as these banks were all considered “too-big-to-fail”.

Within a year, the whole world financial system was teetering on the verge of collapse, and together with it, the capitalist system. It posed the most dangerous situation since the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Find out more about how capitalism works (or doesn’t) at our Capital in a Day event on Saturday 16th September, looking at the relevance of Marx’s writings, 150 years on.

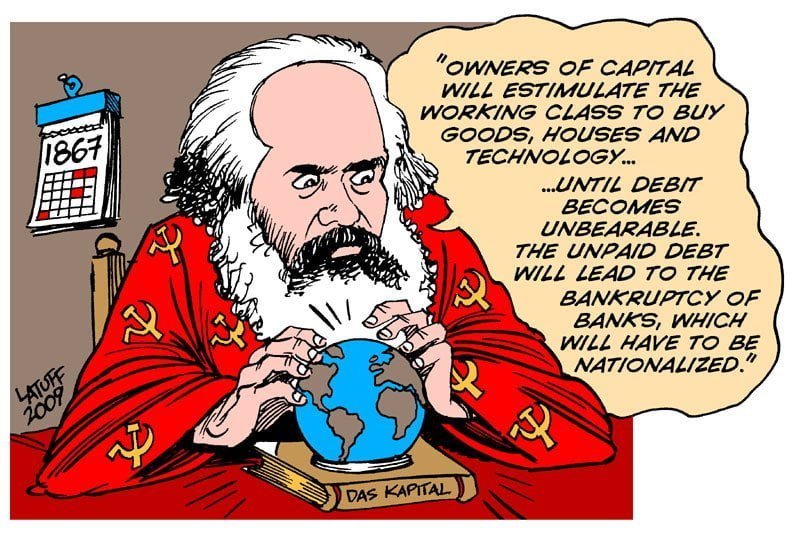

150 years of Marx’s Capital

This month is also the 150th anniversary of the publication of Karl Marx’s Capital. Both, in their own ways – one in practice, the other in theory – revealed the inherent crisis-ridden nature of the capitalist system. Indeed, the analysis contained in Marx’s writings is more relevant in understanding capitalist crisis than anything written before or since.

The threatened collapse of Northern Rock was only the tip of the iceberg. It was a sign of things to come. Of course, a few months before this the financial authorities were all denying any difficulties, saying that “all the fundamentals were sound”, just as they had said just prior to the 1929 Crash. When the financial deluge broke, it came as a complete shock.

More importantly, it provided the catalyst for the biggest crisis of overproduction ever faced by the capitalist system, where world trade crashed by more than a third and millions lost their jobs and houses.

The financial crisis was not the cause of the 2008/9 slump, but it acted as a trigger, just as the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 provoked the economic collapse of 1974. If it hadn’t been the financial crisis, there would have been something else that would have triggered the impending slump.

£1.2 trillion handout

In the end, the British state, using taxpayers’ money, came to the rescue of British banks with a massive bailout worth £1.2 trillion, or 83% of UK annual economic output. This was some handout by a state that regularly denounced poor people as scroungers! Today, we are still paying for the crisis, ten years later, with permanent austerity.

In the end, the British state, using taxpayers’ money, came to the rescue of British banks with a massive bailout worth £1.2 trillion, or 83% of UK annual economic output. This was some handout by a state that regularly denounced poor people as scroungers! Today, we are still paying for the crisis, ten years later, with permanent austerity.

So what had gone wrong? The high priests of the free market had been telling us that markets were always self-correcting and that a slump was ruled out. But this was tomfoolery. The capitalist system is inherently crisis prone. The slump was not due to some freak accident but arose from the workings of the capitalist system itself.

The driving force of capitalism is the maximisation of profit, namely greed, money-making – call it what you will. The money the capitalists make can never be enough. They are driven by competition to undercut their competitors and if possible drive them out of business.

However, this produces its own contradictions. The ferocious drive to reduce “wage costs”, while increasing profits, also serves to cut the market for consumer goods and leads eventually to a cutback in investment, ultimately leading to a crisis of overproduction. This boom and slump cycle is inherent in the capitalist system.

The reason why the 2008/9 slump was so severe was because capitalism, for a whole historical period, went beyond its limits. The longer it put off the slump by artificial measures, primarily through the expansion of credit, the bigger the collapse. But sooner or later credit has to be paid back with interest.

The capitalist system had also reached its limits. Capitalism can only function if it continuously expands, reinvesting the surplus extracted from the labour of the working class and creating a market in the process. But markets are saturated and there is little demand. Given this situation, why should the capitalists invest? Without adequate investment, the whole system grinds to a halt or chronic stagnation sets in.

Some have described the current period as “secular stagnation”. The system can no longer develop the productive forces as in the past. As Marx explained, as soon as a socio-economic system proves incapable of developing the productive forces, industry, technique and science, it enters into decline.

Ever since 1950, the total volume of goods exported has increased at an average annual rate of 6%, which means that it doubled every twelve years. But growth has slowed down over the decades: the value of goods being exported across borders increased six-fold between 1960 and 1980; from 1980 to 2010 the rise was threefold, a 50% drop. It has since declined further. This is a reflection of the impasse of capitalism.

Casino capitalism

As the production of goods and services slows down, the parasitic tendencies within the system have grown rapidly. Currency manipulation, gambling on the bond and stock markets, financial skullduggery and “casino” capitalism have rocketed and are all linked to the dramatic rise of financial markets.

As the production of goods and services slows down, the parasitic tendencies within the system have grown rapidly. Currency manipulation, gambling on the bond and stock markets, financial skullduggery and “casino” capitalism have rocketed and are all linked to the dramatic rise of financial markets.

From 1977 to 2007, the value of trading in currencies increased by 234 times, whereas the value of everything the world produces every year rose just seven times! Currency markets have a turnover of $5.1 trillion a day. In other words, mountains of currencies are being traded that have nothing to do with the needs of the economy. Again, it is a clear reflection of the malaise of the system.

In the 1990s, new financial investments – derivatives – were created which sucked in speculative money. Financial instruments (as they are called) such as credit default swaps, among others with weird and wonderful names, were invented. The capitalists were like the alchemists of old, who tried to turn lead into gold.

This time they were taking bets on the performance of companies. It was like taking out an insurance policy on your neighbour’s house that it would burn down! This is here “insider trading” came into its own.

Debt in all its forms – mortgage debt, student debt, insurance debt, etc. – were cut up into small pieces and bundled together with low grade and “toxic” debt and given a triple-A grade rating by the rating agencies. The riskier the bond, the more it was worth, as the more it would earn.

The infamous sub-prime mortgages were born; the debts of the poorest people were dressed up, sliced up, and sold off to the highest bidder. The value of derivatives grew from nothing in less than twenty years to more than $60 trillion in 2007, greater than the value of entire world GDP!

Financial WMDs

The banks and finance houses were becoming incredibly powerful. They were selling, in the words of American business magnate Warren Buffet, “financial weapons of mass destruction”.

The Financial Times put it quite bluntly recently: “the business model of finance amounts on the whole to skimming the cream off the financial flows coursing through the economy.” And concluded: “that makes for a perverse relationship between the interests of finance and society as a whole.” (FT, 15/8/17)

Making profits the old fashioned way by producing things was now considered old hat. Why not make money from money instead? This was far easier and less time consuming! All you had to do was buy and sell bits of paper.

As investment in real production fell, financial speculation turned into a frenzy. Bankers, capitalists and financial parasites of all kinds jumped onto the bandwagon. They simply climbed aboard a merry-go-round of money making, which only temporarily came to an end with the crash. In the meantime, their arrogance was expressed by the head of Goldman Sachs who went so far as to proclaim that he was “doing God’s work”!

Profit and exploitation

Speculation, however, whilst it can make money, does not create a penny in real wealth. It merely sucks out wealth from the real economy.

Speculation, however, whilst it can make money, does not create a penny in real wealth. It merely sucks out wealth from the real economy.

As Karl Marx explained in Capital, real wealth is not made in circulation or speculation, but in the process of production. It is through the labour of the working class that wealth and therefore profit is generated. In fact, profit comes from the unpaid labour of the working class.

Obviously, if the workers were paid the full value of what they produced, there would be no surplus-value or profit. That is why the working class is paid, not for their labour but for their labour power, their ability to work and produce.

For example, if a worker works an eight-hour day, he or she may work four hours to produce value equivalent to cover their wages and four hours labour goes towards the profits of the capitalist. The same goes for every minute or piece of work that the worker produces. As the commodities are sold on the market, the capitalist uses part of the money he gets to cover the cost of raw materials and the plant he has used, while the new value created in production by the worker is split between wages and profits.

This process of exploitation was easy to see in the Middle Ages when the peasant was forced to work say three days on his own plot and three days for free on the feudal lord’s land. The master was getting something for nothing. He was fed, clothed and housed in his castle by the peasants who did all the work. The lord was able to do this because he owned the land. The peasant was bound to his master’s land as a serf. He produced just enough to keep himself and family alive, the rest went to the upkeep of the lord of the manor, his retainers and servants.

The “free” worker

Today, the worker is free – yes, free to go cap in hand to ask for work from whichever member of the employing class will offer it. He cannot refuse to work, as he cannot survive on thin air. The capitalists have acquired a monopoly of the means of production, the machines, the buildings, etc. The worker has no alternative but to work for the boss. It is the working class that produces everything but they only get a wage to survive on, which they need to repeatedly earn, week-in and week-out, year-in and year-out, until retirement or until death do us part.

Unlike during feudalism, capitalism covers up the exploitation process. But what is happening is essentially the same. The employers, who own the factories, force the workers to hand over the produce of their labour. The workers get wages for their labour power but the rest is all unpaid labour for the bosses. Necessary labour covers the upkeep of the toilers, while the surplus labour they produce becomes the fruits of exploitation for the owners of capital.

Of course, the capitalist needs to borrow money to keep his operation going before he sells his commodities and realises a profit as this may take weeks. No capitalist wants to tie up their money in unsold stocks. Here enters the banker or financier, who demands a slice of the surplus created by the working class. The credit system comes into being to fulfil this need to keep business going. It is to grease the wheels of capitalism – at a price. The middleman is born.

The banker gathers in money that is lying idle, for which he is prepared to pay interest on all deposits. Over time, the bankers dispose of the entire money wealth of society. Savings are then put at the disposal of capitalism, for a small consideration of course. As with capitalism generally, the banks gobble each other up until you have super banks with staggering amounts of cash at their disposal. In Britain, we now have four big banks. They are all considered too big to fail!

So how do the banks make their money? In the popular imagination a bank only lends the money in its vaults. This isn’t the case. Firstly, they lend out money held on deposit and only keep enough money to cover normal daily transactions.

Secondly, the banks “create” money. With deposits of £100, only £10 might be needed to cover daily transactions, leaving £90 available for the bank to use. This is then regarded by the bank as a cash ratio for much greater loans. This £90 in deposits can act to cover the transactions for a further £900 of loans, which the bank lends to a capitalist at a certain rate of interest who then buys new machinery. The seller of machines deposits this “money” into his bank account, but he is only likely to ask for 10% of it, or £90, at any one time – a sum the bank has in its vaults and can easily cover.

Here we assume one bank for simplicity, but the principle is the same across the banking system. We therefore see “loans make deposits” and also fat profits for the bankers. This is called leverage.

Regulation

Therefore, the driving urge of the bank is to lend out to the maximum in order to make more money. All money that is fallow is idle money – not making a penny. It is dead cash. The more money a bank holds the smaller its profits. Only money that is loaned is making money.

Of course, this is dangerous as banks can overstretch themselves. If all depositors lose confidence in the bank and ask for their money back at once, the bank would be ruined. It was precisely such “runs on the bank” that brought down Northern Rock, and others. To stop this temptation to go too far, governments have in the past stepped in to regulate lending.

All banks are told to keep enough money in their reserves to cover all eventualities. But as the banks got more powerful, such rules were increasingly ignored. The urge to make greater and greater profits becomes all too powerful. Ways and means are devised to get around rules and regulations. Governments can try to limit excesses but there are always loopholes, especially in a dog-eat-dog society. When international bankers are making a fortune, it is impossible to call a halt. In any case, money buys influence and politicians.

Just see how the bankers’ profits increased! According to the Bank of England, the return on equity, as it is called, rose from an average of between 5% and 10% in the 1960s to 23% in the decade before 2008. The pay of top bankers also went up between ten- and twenty-fold from 1990 to 2006.

The “leverage” of banks has been steadily rising. In the 19th century, banks would tend to hold capital equivalent to about half their loans. This fell to around 20%. However, by 2008, the Royal Bank of Scotland held reserves equivalent to only 2.2% of their loans and investments. In the case of Northern Rock, the ratio was just 1.7%.

To put it another way, a century ago a bank went bust if a quarter of its loans went bad; in the latest financial crisis, one of the biggest banks in the world, RBS would sink if only 2% of its loans went belly-up.

So ten years ago, the banks were taken to the brink of disaster by reckless lending. It was like a herd instinct. By 2006, a quarter of all loans and investments made by British banks were financed by selling bonds to big investors and borrowing from financial institutions. By 2008, there was a £900bn gap between the money lent and the money they had taken in from depositors. This £900bn was obtained from financial institutions, including other banks. As the crisis spread, these institutions demanded their money back to pay other debts, thereby causing the financial crash.

As the Financial Times put it:

“So financiers will benefit more when they cause more damage and pose a greater danger to the economy. In a very basic sense, what is good for finance is often bad for society. It is entirely legitimate, therefore, to think of much of financial industry remuneration as ill-gotten gains, morally if not legally.” (15/8/17)

A new slump looms

The capitalist system has gone mad. And yet millions of lives depend on this madness. Sick with greed, the bankers and capitalists have taken us to the very edge of disaster and threaten us once again with a new deep slump, with all the consequences that go with it. It is time we put an end to this state of affairs.

Marx provided us with the solution: End the rule of the bankers and capitalists by taking the banks and factories out of their hands and placing them under the democratic control of the working class. At a stroke, this will abolish the anarchy of capitalism, together with its endemic crises and slumps, and allow us to draw up a democratic plan of production. It will be like the planning of a single factory but on a bigger scale.

With the technologies at our disposal, it would be a piece of cake. The resources of society, the fruits of our labour, could then go to those who produce the wealth. Rather than the madness of overproduction and all the wastage and destruction that goes with it, we could rationally produce according to the needs of society. We could establish a society based on the principle: from each according to their ability to each according to their need.

That is the real lesson for working people from the financial crash of ten years ago. It is also the lesson of Marx’s Capital. Let us make it happen.