Myanmar’s masses continue to resist the military junta, which is failing to restore stability. Class tensions are heightening, with an alliance of unions organising a second general strike. All the conditions exist for a revolution.

The Myanmar masses continue to resist the military junta despite mass arrests and dozens of people already killed on the streets. Over one month since the military took over, the junta is still failing to restore any semblance of stability. On the contrary, class tensions are being heightened as an alliance of unions organised a second general strike in response to the military’s continued clampdown.

The masses are determined to get rid of this junta, which is confirmed by the fact that on Sunday we yet again witnessed huge protests, among the biggest of the movement so far. And the only answer the military regime has is to step up repression. For example, in Mandalay, at least 70 people were arrested on Sunday when tens of thousands flooded the streets. Similar scenes occurred in Yangon, the main city, and in other cities across the country. So far, close to 1,800 protestors have been arrested, and over 60 have been killed.

Tensions were also heightened on Sunday when a local National League for Democracy (NLD) leader was found dead at a military hospital after the security forces had abducted him from his home. Apparently, he was badly beaten.

Over the weekend, the police stepped up their campaign of terror. Yangon became more like a hunting ground for the police and army, who locked down certain neighbourhoods of the city. They also occupied hospitals and universities, seeking to arrest protestors who had been injured during clashes on the streets. The security forces attacked and arrested medical personnel, including ambulances and their crews. Gunshots were fired even after the streets were emptied, in a clear intent to terrorise the people.

The military police forces are stepping up their bloody clampdown against the protesting people all over the country as each day passes. More than 300 students and youth are presently being arbitrarily detained in the infamous Insein Prison near Yangon. Via the state-owned media last night, some leading student activists were charged with section 505(A) of the penal code, which states that it is a crime to publish or circulate any “statement, rumour or report”, “with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, any officer, soldier, sailor or airman, in the Army, Navy or Air Force to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in his duty as such”.

This young student leader featured in this video, for example, was arrested on 3 March and is being tortured by the state authorities in the prison. He is a leading student activist and vice-president of All-Burma Federation of Student Unions, ABFSU. Insein Prison is notorious for its terribly inhumane conditions, with the abuse, mental and physical torture of those held there.

However, all this terror is still not having the desired effects. Instead of intimidating the people, the repression is pushing the masses to take even more determined action. As we have seen, Myanmar’s major trade unions – clearly feeling the pressure from below – called on their members to come out in an extended national strike on Monday 8 March, with the aim of a “full, extended shutdown of the Myanmar economy” until democracy is restored.

Strike action and demonstrations

In response to the strike call, major shopping centres were closed, as were the small shops, and many factories. Workers in sectors including construction, agriculture and manufacturing, as well as the healthcare and government workers came out. Big rallies were held in several towns across the country.

Garment workers in Myanmar are shutting down factories across the country as part of the nationwide general strike against the military coup. pic.twitter.com/8JSfkHxkBX

— redfish (@redfishstream) March 10, 2021

In the northern town of Myitkyina, one of the main centres of the ongoing protests, two demonstrators were killed after being shot in the head on Monday. Meanwhile, in the Northern Okkalapa Township, the protests continued despite the fact that security forces were shooting and arresting people.

The strike action is ongoing, but after the weekend, the protest marches have been limited in some areas by the heavy presence of security forces on the streets, particularly in Yangon where the protesters built barricades to defend their neighbourhoods. But in other parts of the country there have been significant protest marches, such as in Mandalay, Monywa, Magway and others.

However, it would also be true to say that the joint trade union statement issued on 7 March, although a welcome development, came somewhat late in the situation. Such a call should have been issued immediately after the coup, and it should have been for an all-out general strike, not just the one day action they called for 22 February, which was a full three weeks after the coup.

This latest call has brought out large numbers, but coming late, it has also found some of the workers showing signs of exhaustion. To keep coming out on strike after weeks of militant action, especially in the private sector, means the loss of wages and an increased risk of losing one’s job. The workers are not getting any significant financial support.

At the same time, the regime is raising the stakes by carrying out a bloody crackdown. In such a situation, it is critical that the workers see a perspective ahead of them, that they are going to achieve victory soon. If not, then despite their total opposition to the regime, they could be facing a situation where they will not be able to energetically carry out united action.

Nevertheless, it is a credit to the Myanmar workers, that in spite of this difficult situation, they are still fighting on the streets of Hlaingtharyar, one industrial township of Yangon. Most of the industries are located in this slum area, and even if the military presence on the streets has stopped workers from marching to the centre of Yangon, they are protesting in their local areas.

Another example is the regime’s attempts to force the workers in the private banks to maintain business as usual. So far, they have only succeeded in reopening the military-clique-owned banks. The rest are still paralysed by strike action, which yet again shows how strong the opposition is.

These developments, in spite of the determination of the workers, confirm that revolutionary conditions cannot last forever. The most favourable of conditions can be thrown away by the weak and indecisive leadership

In Yangon, in the Sanchaung district, hundreds of young protesters were trapped by security forces overnight on Monday, with police firing guns and doing house-to-house checks to find anyone from outside the district that had been sheltered by local residents. Eventually, the youth were able to get out on Tuesday morning. Thousands of protestors had turned out, defying the overnight curfew, in support of the youth. There was widespread support for the protestors, which could be seen when the local residents, risking severe punishment from the security forces, sheltered the youth in their homes. Also, many people with cars brought the youth to safety.

The call for extended strike action on the part of nine unions was a welcome development. But as we have seen, what is required is an all-out extended general strike whose aim must be to paralyse the whole country.

But this is the second time that a general strike has been called, and so far the military are not budging. The military chiefs are fully conscious of the fact that now they have a lot to lose if they are forced to hand back the government to civilian politicians. The masses will not be happy with a mere “return to barracks” of the army, but will demand justice for the killings perpetrated by the army and police.

Unrest among the police

This brings us to the question of the “armed bodies of men”: the army and the police, at the service of the propertied, privileged classes. People are used to the idea that the purpose of an army is to defend their country, and that also means the people who live in it. The Myanmar military officers do not have a good record when it comes to defending their own people. On the contrary, on more than one occasion, they have killed hundreds and even thousands, such as in 1988. They also have a brutal track record when it comes to the treatment of ethnic minorities, such as the Rohingya and others.

One of the important tasks of a genuine revolutionary leadership in Myanmar would be to work to break down the army ranks along class lines. For this to happen it would require a movement that shows the ranks of the military and the police that it is working to overthrow the whole rotten system, and not just bring back the NLD.

Let us not forget that the economic programme of the NLD includes greater privatisation, which means enriching the few at the cost of the many. Let us also not forget that the NLD government participated in the oppression of the ethnic minorities. While the masses desire an immediate end to military rule and a return to civilian government, that in itself would not remove the danger of a return of the military chiefs at some later stage. The NLD when it was in office did little or nothing to remove the powers of the military, and therefore any insubordination among the ranks of the military and the police still risks severe punishment.

Despite all this, it is amazing to see some of the police refusing to be used against the masses. The famous communist poet, Berthold Brecht, in one of his poems wrote: “General, man is very useful; He can fly and he can kill; But he has one defect: He can think.”

While the bulk of the police continue to carry out orders, there is growing unrest among at least a section of the ranks of the police, as they are forced day after day to repress their own people. But the determination of the masses is showing what could be possible if a clear revolutionary lead were provided.

The scenes of a Catholic nun appealing to the police not to shoot at the youth show, albeit in a distorted manner, what impact an appeal to the ranks of the security forces could have:

INCREDIBLE: Sister Ann Rose Nu Tawng, a Catholic nun in northern Myanmar, knelt before a group of armed police officers begging them to spare the children and to take her life instead. Two of the policemen then knelt in a show of respect. Photo by AFP. (Reuters video below) pic.twitter.com/Z1PtQGxeEy

— Vivian Salama (@vmsalama) March 10, 2021

It is not easy for ordinary police officers to come out against their superiors. They know they risk a lot if they do so. For widespread insubordination to take place, the rank-and-file police would have to be convinced that the mass movement is going to overthrow the present military junta and that those who would replace them would protect them against any disciplinary measures.

Unfortunately, the NLD leaders are not providing the kind of leadership that is required. That is why the recent reports of police officers breaking ranks is even more significant, and it provides a glimpse of what would be possible with a genuine revolutionary leadership of the working class.

According to France

“Some police have refused orders to fire on unarmed protesters and have fled to neighbouring India, according to an interview with one officer and classified Indian police documents.

“‘As the Civil disobedience movement is gaining momentum and protest(s) held by anti-coup protesters at different places we are instructed to shoot at the protesters’, four officers said in a joint statement to police in the Indian city of Mizoram. ‘In such a scenario, we don’t have the guts to shoot at our own people who are peaceful demonstrators,’ they said.”

The Irrawaddy (5 March 2021) reported that: “More than 600 police officers have joined Myanmar’s civil disobedience movement (CDM) against the military regime…” The same report added that: “The numbers of police resignations have risen sharply since the violent crackdown in late February.” Several hundred police officers have actually joined the protest movement.

Most significant is the fact that: “Police participating in the CDM said they would only accept an elected government. Some said they would offer their service if the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, representing elected members of the Union Parliament from the National League for Democracy, forms an army to fight the military regime.”

The potential for such an army is present everywhere. If an open call to rebel were issued to the rank-and-file police and the soldiers, the security forces could start to crack, with a significant section going over to the revolutionary movement against the coup.

For this to happen, however, the movement would have to give itself a structure – as we explained in previous articles – of elected action committees in the workplaces, the neighbourhoods, the villages, all coordinated up to a national committee that could present itself as the voice of the masses. Such a body would have the authority to appeal to the ranks of the police and army and split them along class lines.

But it wouldn’t be just a question of splitting the military forces, but also of organising workers’ self-defence groups that could become the backbone of a workers’ armed defence force. Such a force, backed by the masses in the workplaces, in the rural areas, in the city neighbourhoods, schools and universities, would be invincible.

The fact that calls for self-defence pickets have received a widespread echo among the people, especially the youth, and that there have even been appeals to the ethnic armed organisations to form a federal army in order to counter the state military, underlines the point that this is an extremely favourable revolutionary situation. But the lack of leadership is the key factor that is missing.

Self-defence is not something the NLD leaders are going to organise. They represent the interests of capital, and therefore will not work to undermine the instruments of the bourgeois state. What is required is an independent party of the working class, a party that would issue a revolutionary appeal to the workers to take power and in the process split the armed forces along class lines.

UN and the US

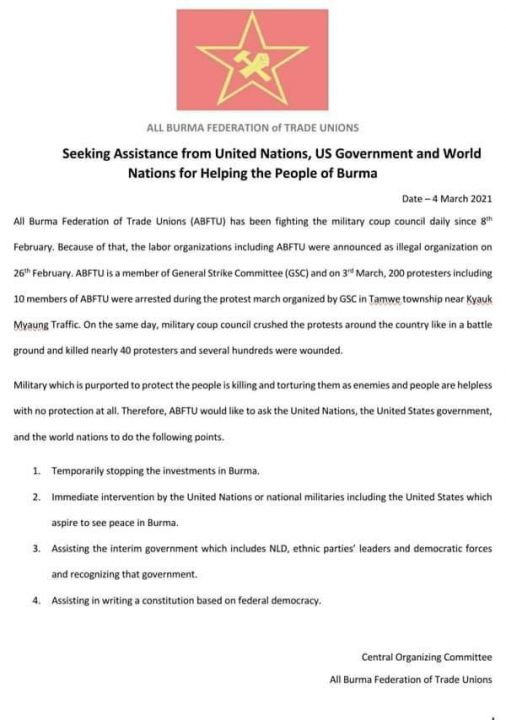

The tragedy of the situation is that the masses would respond enthusiastically to such a call. But because there is no leadership that is prepared to take the road of revolution, we see appeals being issued to bodies such as the United Nations, and even to the USA. Appeals have been issued calling on them to intervene in Myanmar and remove the military from power. An example is a statement issued by the All-Burma Federation of Trade Unions on 4 March 2021:

The United Nations is presently quibbling over the wording of resolutions, as some of the powers refuse to use the word “coup” to describe the military takeover. China and Russia in particular are in conflict with the United States and the European Union over how to react to the coup, and that is because they have different interests in the country.

For the US and the EU, it is Aung San Suu Kyi (ASSK) and the NLD that best represent their interests in the country. These imperialist blocs want to further open up the economy of Myanmar, as we explained in a previous article. That explains why they are so enamoured with “democracy” in Myanmar.

Unfortunately, for those who drafted the above letter, the track record of both the US and the EU in promoting “democracy” is patchy to say the least. They make noise about democracy when it suits their interests. When it doesn’t, they turn a blind eye and get on with business as usual. This is the case with Saudi Arabia, where there is a brutal regime, but because it suits the west to have working relations with the Saudis, as they have such a large reserve of oil, there is no talk of condemning the regime.

Furthermore, beyond a few words of condemnation and some sanctions imposed on a few individuals at the top of the military regime, the United States is not going to send any military forces to Myanmar, for this would be a direct confrontation with China, which they cannot afford to provoke at this stage.

The role of China

The one power that has real weight in Myanmar – far more than the United States – is precisely China, whose official policy is “non-interference”. “China will not change the course of promoting friendship and cooperation, no matter how the situation evolves,” Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister recently stated. He added that China seeks reconciliation by engaging with both the ousted civilian government and the present military junta.

The one power that has real weight in Myanmar – far more than the United States – is precisely China, whose official policy is “non-interference”. “China will not change the course of promoting friendship and cooperation, no matter how the situation evolves,” Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister recently stated. He added that China seeks reconciliation by engaging with both the ousted civilian government and the present military junta.

The Chinese regime desires more than anything else stability in Myanmar, for it has a lot of economic interests in the country, which it considers as falling within its sphere of influence. Myanmar has an abundance of natural resources, and its proximity with China – a shared 2,129km long border – and the imposition of sanctions by the west in 1990, meant that the country became one of China’s strategic economic partners in the region. After the year 2000, China’s dominance of Myanmar’s economy grew significantly.

Xi Jinping visited Myanmar in January 2020 and signed together with ASSK “…33 agreements shoring up key projects that are part of the flagship Belt and Road Initiative, China’s vision of new trade routes described as a ‘21st century silk road’. They agreed to hasten implementation of the China Myanmar Economic Corridor, a giant infrastructure scheme worth billions of dollars, [$100 billion according to some sources] with agreements on railways linking southwestern China to the Indian Ocean, a deep sea-port in conflict-riven Rakhine state, a special economic zone on the border, and a new city project in the commercial capital of Yangon.” (Reuters, 18 January 2020)

China, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, with its right of veto, will therefore not back UN sanctions, and it totally rules out any external intervention. So, what is China hoping to achieve in Myanmar? Is it actively supporting the military? The truth is that China will back anyone who can guarantee calm and stability and a good business environment.

Before the coup they had established a good working relationship with ASSK and the NLD, as the latter understood full well that it was also in their interests to maintain good relations with its largest trading partner – and also one of the biggest providers of foreign direct investment – on their northern border. In fact, China’s relations with Myanmar actually improved after the National League for Democracy formed a government. The Chinese regarded ASSK as someone who could guarantee stability.

The Chinese ambassador to Myanmar Chen Hai recently issued a statement in which he said, “Both the National League for Democracy and the Tatmadaw maintain friendly relations with China.”

So who will China back? The regime in Beijing sees the present turmoil in Myanmar as a threat to the huge investments it has poured into the country over the past decade. Therefore, they will back whoever can guarantee an environment that protects their business interests. If the junta can prove they can provide that stability, then China will establish working relations with them. If, on the other hand, the junta fails to stabilise the country and bring things back under control, one can be sure that, despite their policy of “non-interference”, they will use China’s economic muscle to push the generals towards some kind of deal with the NLD and ASSK.

The key role of China, and the relative weakness of US imperialism in the country, explains why US State Department spokesman Ned Price stated after the coup that:

“We have urged the Chinese to play a constructive role to use their influence with the Burmese military to bring this coup to an end.”

The irony of the situation is that it is precisely the moderate stance of the NLD that is facilitating the military regime. Even from their own limited bourgeois liberal point of view, taking the movement to a higher level, and making it impossible for the military to consolidate their regime, would push the Chinese bureaucrats to lean on the military chiefs to make a deal and prepare to withdraw in favour of a return of formal bourgeois democracy.

International working-class solidarity

Appeals to the United Nations, to the US or the EU, are not worth the paper they are written on. In Myanmar there is a conflict of interests between the major powers and therefore no amount of appealing to the UN is going to provide the help the Myanmar masses require. The trade union leaders should not be sowing illusions that such appeals can actually achieve anything. What they should be doing is appealing to the workers of the world.

Appeals to the United Nations, to the US or the EU, are not worth the paper they are written on. In Myanmar there is a conflict of interests between the major powers and therefore no amount of appealing to the UN is going to provide the help the Myanmar masses require. The trade union leaders should not be sowing illusions that such appeals can actually achieve anything. What they should be doing is appealing to the workers of the world.

They should start with an appeal to the workers of South-East Asia, where we already have ongoing movements, such as in Thailand and Malaysia. In South Korea, there have already been solidarity protests with the Myanmar masses. Such appeals could have a significant impact. Already we see how the three-fingered salute, first adopted in Thailand after a coup there back in 2014, has crossed national borders, and has been used on street protests in Myanmar. This highlights the fact that the protestors see themselves as part of an international movement.

If the Myanmar trade union leaders were to issue an appeal not just for street protests, but also concrete workers’ actions in the neighbouring countries, this would also put big pressure on the respective regimes. The problem we have is that the trade union leaders everywhere are totally wedded to the capitalist system in their respective countries and do not think in terms of independent, working-class action.

But it is not at all utopian to think in terms of international working-class solidarity. We have had examples in the past of initiatives at local and rank-and-file level. Back in May 2019, we had the example of Italian unions in Genoa who refused to load electricity generators onto a Saudi Arabian ship that was transporting weapons. The ship had previously loaded weapons in Belgium, and on its way had stopped in Le Havre in France to load more weapons, but was stopped by the French dockers. This was a protest by the French and Italian workers against Saudi Arabia’s continued support for the war in Yemen.

Another Saudi ship was also forced to leave the French port of Fos-sur-Mer without being able to load arms destined for Saudi Arabia. Back in 2008, we had the example of a Chinese shipment of arms for Zimbabwe, which had to be recalled after South African dockers, in solidarity with their fellow workers in Zimbabwe, refused to unload it.

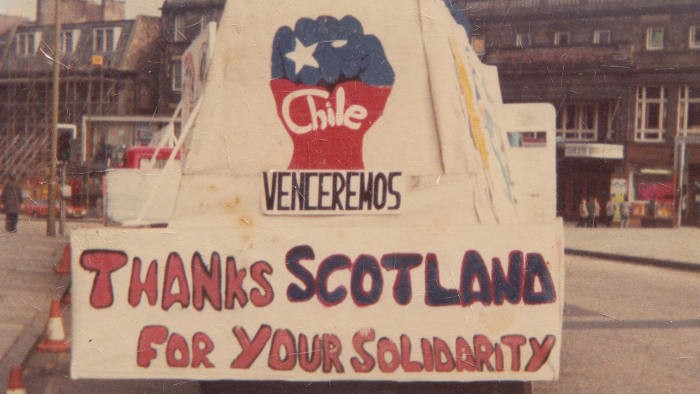

When the infamous Pinochet coup took place in Chile in 1973, we saw many examples of worker boycotts of the regime. One example was the Scottish workers’ boycott when Chilean air force jet engines were sent to the Rolls-Royce plant in Scotland a year after the coup, but the workers refused to work on them.

These have mainly been rank-and-file initiatives taken by workers in one country in solidarity with workers in other countries. Today, if the Myanmar trade union leaders, instead of addressing themselves to the United Nations and the United States, were to issue a call for concrete actions by workers around the world there would undoubtedly be a response.

Thus, independent working-class action is required both inside Myanmar and in the international arena. With a bold, revolutionary initiative on the part of the workers’ leaders in Myanmar, combined with international working-class solidarity actions, this bloody regime could be brought down.

However, without the revolutionary leadership required, the military junta could survive, at least for a brief period. They are counting on the lack of leadership and hoping that, by piling on the pressure, increasing the violent clampdown, and hunting down the activists, they may eventually achieve some kind of stability.

What chances do they have of achieving this? At present they are in a deadlock. But when the masses are exhausted, with the lack of revolutionary leadership, the junta could achieve this, which would mean a temporary stabilisation under military rule. However, even if this were to come about, it would be a regime with no social base, and therefore would not be able to survive as long as the previous military regimes.

Without a social base, it would only be able to rule by the sword and that means it would be a weak and unstable regime. There is a whole new generation of workers now that has become accustomed to having trade unions, the right to strike, and so on. Added to this, there will be the pressures of the world crisis of capitalism. The social and economic conditions will worsen, and therefore the military regime will have no legitimacy whatsoever in the eyes of the masses. It would therefore not be a long-lasting regime.

All the conditions exist for revolution, but it requires a determined revolutionary socialist leadership to transform the potential for revolution into a successful overthrow of the regime and the transformation of society.