Voting begins today for the Young Labour elections. Now more than ever, we need a fighting socialist leadership. The militant stance taken by the Labour Party Young Socialists provides an inspiring reference point for activists today.

Voting opens today to elect the new national committee of Young Labour. Socialist Appeal supporter Lewis Griffiths is running for the position of Wales Representative on the Young Labour national committee, as part of the official Momentum slate.

Lewis succeeded in the Momentum Young Labour primaries by running as part of the “socialist seven” of Marxist young activists.

Their campaign – the Marxist Voice for Young Labour platform – raises socialist answers to questions such as the fight against racism, the housing crisis, and the battle against the right wing inside the Labour Party.

Combined with this is the need to transform Young Labour into a dynamic, militant youth wing, taking inspiration from the Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS) of the past.

Below we publish an article from Kevin Ramage, who was the National Chair of the LPYS from 1979-1983. Kevin details how on the basis of bold socialist ideas and Marxist leadership, the LPYS became a powerful organisation of overwhelmingly working class youth that challenged the attacks of capitalism on all working class people.

The inspiring history of the LPYS provides many lessons for young activists in the struggle against capitalism today.

The Labour Party Young Socialists was set up in 1965. By 1970, the LPYS had adopted a clear socialist programme. Then in 1972, Militant supporters – the Marxist tendency of the time – formed a majority of the eleven regionally-elected National Committee.

In the early 1970s, the LPYS produced its ‘Charter for Young Workers’, a massively successful document used to actively draw young workers into the labour movement and support their activity in the trade unions.

The Charter focussed on demands like a proper minimum wage, full adult pay rates for young workers, proper paid training during working hours, and guaranteed jobs for apprentices.

The Charter was written by LPYS national committee members, who were industrial and white-collar workers and trade union activists. It was used to build the LPYS as an organisation of overwhelmingly working class youth.

Political training

LPYS branches usually met weekly, giving members a solid political and organisational training to play a full part in every level of the Labour Party and trade unions. Residential weekend political education schools were organised on a regional level.

LPYS branches usually met weekly, giving members a solid political and organisational training to play a full part in every level of the Labour Party and trade unions. Residential weekend political education schools were organised on a regional level.

The LPYS National conference was always a highlight of the year. By the early 1980s over 2,000 young people would regularly attend. Over 400 branches sent delegates and resolutions, which were debated for three days over the Easter weekend. Major figures from the labour movement came to give keynote speeches, including Tony Benn, Dennis Skinner, and Arthur Scargill.

From 1978, the LPYS also organised an annual week-long summer camp, taking over a field in the Forest of Dean and turning it into a mini ‘workers republic’. This included a full programme of political education seminars, but also sports, quizzes, film nights and legendary club nights. Everything was organised by the LPYS from a very busy creche, to a daily medical tent staffed by LPYS members who were health workers.

Internationalism

Internationalism was always at the forefront of the politics and activity of the LPYS. Starting from the early 1970s, the Spanish Young Socialists Defence Campaign organised financial support and solidarity for comrades in the Spanish underground. After the overthrow of the Allende government in 1973, the Chile Socialists Defence Campaign was organised.

We always saw international campaigns as having two elements. Firstly, the all-important raising of practical and financial solidarity with workers in struggle, and secondly, one of raising the political awareness of the British Labour movement of workers’ struggles internationally.

Another example of the LPYS’ internationalism was the campaign during the 1975 EEC referendum campaign. The LPYS rejected the prospect of a capitalist Europe. But at the same time, it countered the narrow flag-waving nationalism of some of the Labour left of the time, campaigning on the slogan: “No to the Bosses EEC – Yes to a Socialist United States of Europe”.

Anti-racism

The LPYS was always at the forefront of fighting racism and fascism.

In the 1970s the fascist National Front’s gangs of booted, swastika waving thugs were a growing threat to Black and Asian communities, and also to the labour movement. The LPYS was the first section of the labour movement at this time to organise a national rally against racism, gathering over 3,000 in 1974 at a demonstration in Bradford against racist attacks.

Advocating a class approach ‘Black and White Unite and Fight’ and ‘Workers’ Unity to Defeat Racism’ were cornerstone slogans. The LPYS stood in the front line alongside local Black and Asian youth on the streets, such as at the Battle of Lewisham in 1977, where the LPYS played a vital role in ensuring the fascist National Front were sent packing.

Campaigning

When LPYS campaign initiatives were blocked by the Labour officialdom, we found independent ways to campaign. With unemployment spiralling upwards in the late 1970s, we set up the Youth Campaign Against Unemployment. This organised a conference of 1,450 in attendance, and 1,500 at a lobby of parliament.

When LPYS campaign initiatives were blocked by the Labour officialdom, we found independent ways to campaign. With unemployment spiralling upwards in the late 1970s, we set up the Youth Campaign Against Unemployment. This organised a conference of 1,450 in attendance, and 1,500 at a lobby of parliament.

In the early 1980s, the Tories set up Youth Training Schemes (YTS) to mask mass youth unemployment. Participants were paid as little as £15 a week. The LPYS fought for trade union rights and rates of pay with a guaranteed job for all trainees.

The height of the YTS campaign came in 1985 when the LPYS played a leading role in organising school student strikes across the UK. These strikes were against the government’s proposals to make the youth training schemes effectively compulsory for all young people, through the removal of unemployment benefits for 16-17 year olds.

250,000 took part with large demonstrations in many cities, including 10,000 in Liverpool alone. The strikes were victorious, leading to the Tories withdrawing the proposals.

Solidarity

When the Miners’ strike erupted in February/March 1984, the LPYS immediately mobilised. LPYS members supported picket lines, organised joint meetings with the National Union of Mineworkers and raised over £250,000 for miners’ support groups.

In April 1984, the annual LPYS conference took place in Bridlington, attended by over 2,000 young people, including 100 young miners – many of whom went on to become active members of the LPYS.

Rule or ruin

The LPYS reached a high point of 581 branches in 1985, regularly organising demonstrations and protests against the Thatcher government. But sadly, this wasn’t to last. The bitter industrial defeats in the mid-80s lead to the advance of neo-liberalism at the top of the Labour Party, as the right-wing gained ascendancy.

The LPYS reached a high point of 581 branches in 1985, regularly organising demonstrations and protests against the Thatcher government. But sadly, this wasn’t to last. The bitter industrial defeats in the mid-80s lead to the advance of neo-liberalism at the top of the Labour Party, as the right-wing gained ascendancy.

In 1985, the previously ‘left-wing’ Neil Kinnock had become leader of the party, and began to try and expel Militant supporters. Meeting resistance to expulsions from Constituency Labour Parties up and down the country, the leadership turned their venom onto the youth movement.

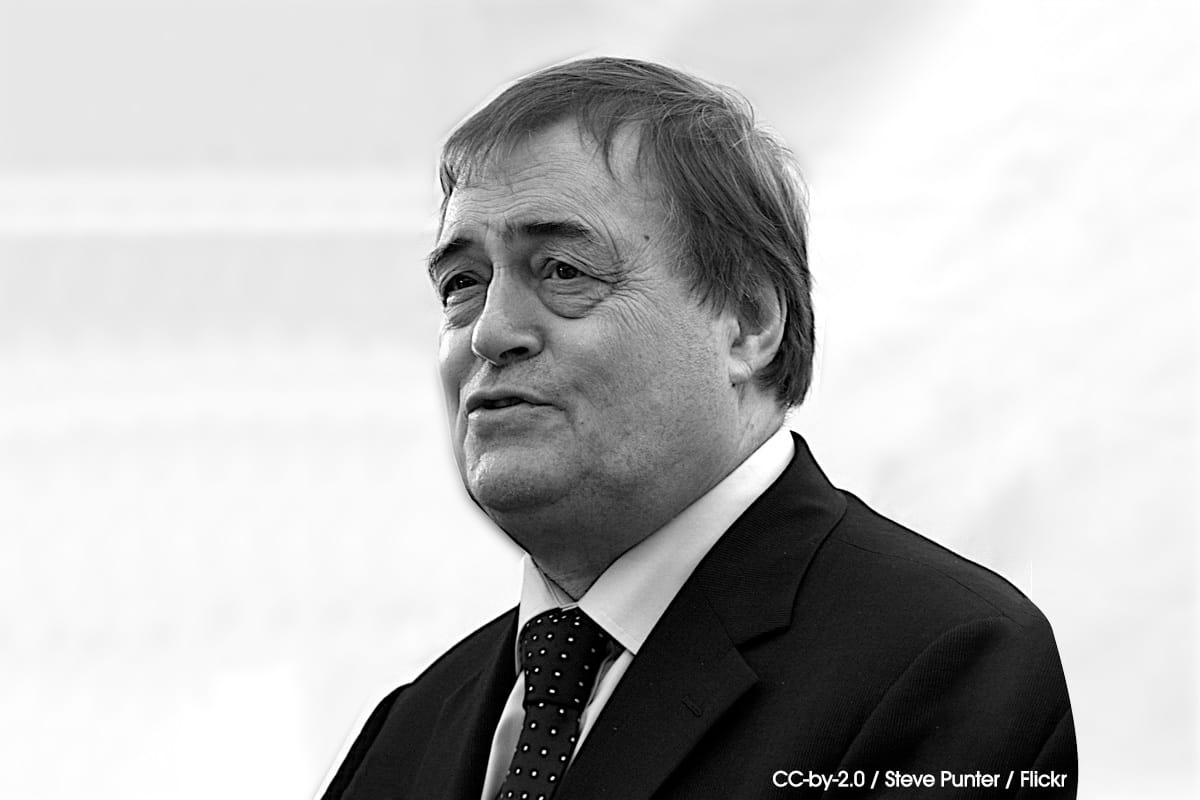

John (now Tory-appointed ‘Lord’) Mann – a bitter opponent of the LPYS leadership since his days in the Labour student movement – wrote a pamphlet that accused Militant supporters of “deliberately limiting membership” of the LPYS in order to maintain its dominant position.

Why this was necessary, given that around 90% of branches supported the Militant, was never made clear by Mann. Nor was it clear how the increase in the number of LPYS branches from a couple of hundred in the early 1970s to nearly six hundred in 1985 constituted ‘limiting membership’!

Nevertheless, in 1987, the right-wing forced through the Labour Party conference policies to cut the age limit of the LPYS from 26 to 23, and to abolish the democratic national and regional structures. As a consequence, much of the leadership and approximately half of the 10,000 members were excluded from the LPYS.

By the end of the decade, only 52 branches, with approximately 300 members, still existed, while national conferences attracted under 200 people (compared to nearly 2,000 a few years earlier). And the right-wing accused us of “deliberately limiting” the membership!

Reduced by the bureaucracy to a shell, the LPYS was wound up on the initiative of a motion at Labour Party conference, moved by one Tom Watson. So, the right-wing destroyed a once vibrant working class youth organisation in the name of ‘rule or ruin’.

The LPYS may have passed into history but it left a tremendous legacy. It showed what can be achieved by a socialist youth organisation which campaigns with verve and enthusiasm around a programme for radical socialist change.