A recent Labour report outlines plans to curb outsourcing and bring public services back in-house. Such a move could not come soon enough. The profiteers and parasites have been getting fat off of the public purse for far too long.

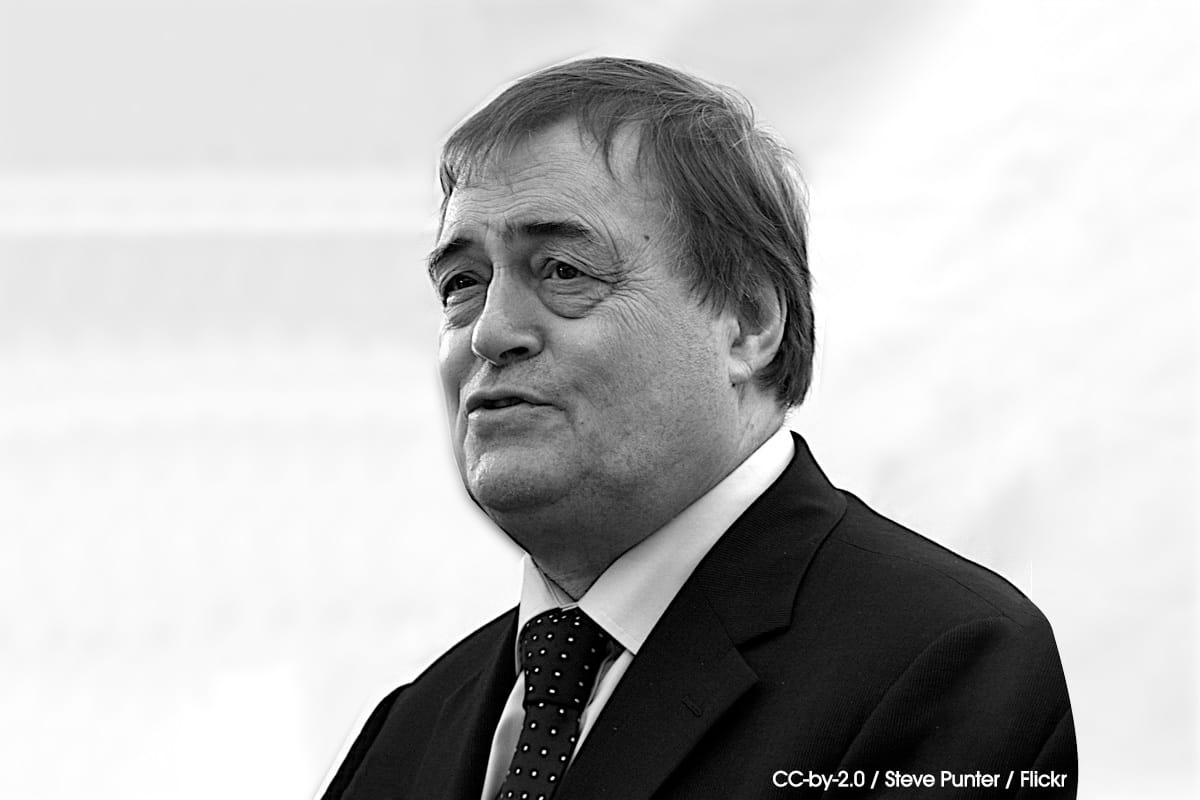

Last month, Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell and Andrew Gwynne, the Shadow Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, announced the release of a report entitled Democratising Local Public Services. This puts forward a plan to tackle the outsourcing epidemic and rebuild our local public services after decades of damage by profiteers.

The report claims that the fight against outsourcing provides us with “an opportunity to reassert at the local level the value of collective ownership”. This is certainly the case. The disastrous collapse of private outsourcing giants like Carillion and Interserve in recent years has put the question of control over our public services firmly back on the agenda.

Where outsourcing began

The report begins by looking at the origins of outsourcing, pinning the blame on the privatising agenda pursued by Thatcher and the Tories.

In the 1970s, local council workers were among the most unionised and militant workers in Britain, and therefore posed a threat to the ascendant Thatcher government. Outsourcing provided an opportunity for the Tory government to break up the workforce and undermine the strength of organised labour, thus allowing the capitalist class to double down on wages and conditions.

This also provided an easy sources of profits for big business, who could feed off the public purse with little risk and potentially huge returns – all at our expense of course.

The process began with the Local Government and Land Planning Act in 1980, which made it compulsory for construction and maintenance contracts above a specified value to be put out for tender. This was then gradually extended to other services, as outlined in the legislation that followed.

This plunder was then consolidated under New Labour. Private Finance Initiative contracts locked many local governments into long-term contracts, with little evidence that they would be efficient or cost-saving.

Despite the delusional claims of services being made more efficient by the ‘rigour’ of the free market, by 1993 two-thirds of contracts were still won in-house. The sluggish progress of privatisation shows just how unfavourable it was to local councils.

What went wrong?

With a number of local authorities bringing their contracts back in-house recently, it is worth taking a look at why these outsourcing companies failed to live up to their expectations.

With a number of local authorities bringing their contracts back in-house recently, it is worth taking a look at why these outsourcing companies failed to live up to their expectations.

The report correctly points out that private companies, being motivated solely by profit, have little incentive to go beyond the bare minimum required in their contracts. At the same time, they have a huge incentive to cut corners to maximise their profits. Doing jobs ‘on the cheap’ and with lower wage bills would prove to be the only skills the outsourcers would ever bring to the table.

Furthermore, a lack of accountability is cited as a reason for the failure of outsourcing. This is certainly true: as these companies are not subject to freedom of information laws, they can get away with all manner of dodgy deals, such as the scandalous asset stripping that came to light following the collapse of Carillion last year.

The financial troubles faced by Carillion, Interserve, and the rest demonstrate the ultimate failure of these crooked ventures. They couldn’t even make a success of ripping us off.

Carillion, for example, went bust after failing to generate enough income to pay its debts. They just kept taking on new publicly-funded contracts to raise the cash needed to pay the bills arising from old ones. Simply put, the firm’s operations were a giant Ponzi scheme.

At the same time, money was flying out of the company’s bank accounts and into the pockets of the managers and the shareholders – over 300% of earned income in its final year. Hedge funds vultures, meanwhile, starting betting on the company’s collapse.

In the end, we ended up paying for this fiasco: the workers made redundant, the projects left unfinished, and the bills unpaid.

Surely this was just an unfortunate one-off? But no! Step forward one year and other outsourcing companies were in trouble. First up was Interserve, with its 45,000 UK employees, which slipped into administration in March of this year.

We can also turn to the outsourcing ‘success story’ that is the Crossrail project. Supposed to open last year, it was ‘suddenly’ discovered that the project was years behind schedule. Promised shiny new stations, in some cases, were still just muddy holes in the ground.

We could go on and on. Housing projects that were built on the cheap; schools that are not fit for purpose; workforces outsourced in such a way that wages and conditions continually fall, yet costs to the taxpayer somehow rise. This is the reality of the outsourcing scam perpetuated by the capitalist class over decades.

Why insource?

The report cites efficiency as one of the main benefits of ‘insourcing’. Due to the fact that local authorities can combine and coordinate services to a greater extent than private companies, they could save a lot of money by insourcing. A survey by APSE has revealed that, among 140 councils who had insourced their services, 63% anticipated savings – with some expecting to save more than £1 million per year!

The report cites efficiency as one of the main benefits of ‘insourcing’. Due to the fact that local authorities can combine and coordinate services to a greater extent than private companies, they could save a lot of money by insourcing. A survey by APSE has revealed that, among 140 councils who had insourced their services, 63% anticipated savings – with some expecting to save more than £1 million per year!

With this in mind, councils have every reason to cut out the corporate middlemen. This would mean less money spent lining the pockets of millionaires, and more money to spend on socially useful projects.

Furthermore, bringing services in-house means that providers could be held to account by the public, as the providers would be subject to freedom of information laws, as well as scrutiny from local councillors.

Labour’s plan

The plan set out in the report can be broken down into three main tasks.

The plan set out in the report can be broken down into three main tasks.

Firstly, a Labour government would pass legislation making in-house provision of services the default option for councils. If councils wished to continue outsourcing, they’d have to defend their reasons for doing so.

Secondly, where outsourcing continues, Labour would aim to strengthen the standards in the contracts, particularly regarding factors like service delivery and workers’ rights.

Lastly, Labour plan to facilitate insourcing with their Community Wealth Building Unit – a national body which can support councils in their campaigns to bring services back in-house. This would be alongside the provision of a forum for skill-sharing, so that councils can deliver local services to the highest standard.

These proposals are certainly a step in the right direction. However, it is doubtful whether – taken alone – they will be enough to roll back the onslaught of privatisation.

Even if in-house provision became the default option for councils, without the necessary funding, it is doubtful whether they would be any more successful than the companies they seek to replace. The fight against outsourcing must therefore also be a fight against austerity – and thus a fight for socialism.

Furthermore, in-house provision is not a guarantee that services would be carried out well, nor that workers’ rights would be respected. One of the reasons public sector unions were so militant in the 1970s was precisely because of the way management operated, often indistinguishable from bosses in the private sector.

More recently, under both New Labour and the Tories, public sector workers have continued to see their rights and conditions eroded and attacked. We have even seen the introduction of zero-hour contracts in the public sector in some cases. The demand for in-house public services must therefore also be accompanied by the demand for democratic workers’ control and management.

The need for nationalisation

Labour’s report offers a much-needed break with the failed outsourcing model. But it still does not go far enough in the boldness of its demands. Instead of gradually winding down outsourcing, for example, Labour should be demanding an immediate end to all outsourcing and privatisation.

Labour’s report offers a much-needed break with the failed outsourcing model. But it still does not go far enough in the boldness of its demands. Instead of gradually winding down outsourcing, for example, Labour should be demanding an immediate end to all outsourcing and privatisation.

All existing contracts and projects should be brought back in-house, into public ownership and under democratic control, with no compensation to the fat cats. And the big outsourcing giants should be nationalised and put under workers’ control – again, with no compensation to the parasites who have fed themselves off the public purse for years.

In order to fully realise Labour’s plan to democratise local services, we need to end austerity and the anarchy of the market. This means bringing in a socialist economic plan, expropriating the outsourcing giants, the top banks, and the major monopolies in order to provide fully-funded public services.

If these companies were nationalised under democratic workers’ control, their enormous resources could be freed up and used as part of a socialist plan of production. Only in this way can we ensure the provision of high-quality public services – run for society’s needs, not shareholders’ profits